George Mason University School of Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prominent Political Consultant and Former U.S. Senator Serve As Sanders Scholars

Headlines Prominent political consultant and former U.S. senator serve as Sanders Scholars wo renowned individuals joined the promote the administration’s agenda. He was later appointed U.S. ambassador TUniversity of Georgia School of Law fac- Currently, Begala serves as Research to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. ulty as Carl E. Sanders Political Leadership Professor of Government at Georgetown Among the numerous recognitions he Scholars this academic year – Paul E. Begala, University and is also a political analyst and has received are: the Federal Bureau of political contributor on CNN’s “The commentator for CNN, where he previously Investigation’s highest civilian honor, the Situation Room” and former counselor to co-hosted “Crossfire.” Jefferson Cup; selection as the Most Effective President Bill Clinton, and former U.S. Sen. While on campus, Begala also delivered Legislator by the Southern Governors’ Wyche Fowler Jr. a speech to the university community titled Association; and the Central Intelligence During the fall semester, Begala taught “Politics 2008: Serious Business or Show Agency “Seal” medallion for dedicated ser- Law and Policy, Politics and the Press, while Business for Ugly People?” vice. Fowler is teaching a course on the U.S. Currently, Fowler is Named for Georgia’s 74th governor and Congress and the Constitution this spring. engaged in an interna- 1948 Georgia Law alumnus, Carl E. Sanders, As a former top-rank- tional business and law the Sanders Chair in Political Leadership was ing White House official, practice and serves as created to give law students the opportunity political consultant, cor- chair of the board of the to learn from individuals who have distin- porate communications Middle East Institute, a guished themselves in politics or other forms strategist and university nonprofit research foun- of public service. -

23Rd Annual Legislative Forum October 4, 2018 Legislative Forum 2018

GOVERNMENT AFFAIRS RIGHT TIME. RIGHT PLACE. RIGHT SOLUTION. 23RD ANNUAL LEGISLATIVE FORUM OCTOBER 4, 2018 LEGISLATIVE FORUM 2018 Maine could make national headlines this November because of the number of key races on the ballot this year. With important seats up for grabs and two political parties looking to score “big wins” in our state, the only thing we can predict about our political forecast is that it is unpredictable. • Who will be Maine’s next Governor? • Which party will take control of the State Legislature? • Will incumbents prevail in Maine’s first and second Congressional districts? • Who will win the race for U.S. Senate, and will the result impact the balance of power in Washington? With so much up in the air here in Maine and a stagnant climate looming over Washington, our Legislative Forum’s key note speaker, CNN commentator Paul Begala, will offer his unique perspective and insight on today’s political landscape. He will discuss why Maine’s races will be closely watched and talk about the impact the 2018 midterm elections will have on our country and state. Begala will also offer his thoughts on the biggest issues facing Congress and how the election will impact Washington’s agenda. We’ll also bring to the stage radio power duo Ken and Matt from WGAN Newsradio’s Ken & Matt Show to share their political humor and insights with our Forum guests. Through their comedic banter, they will give “their take” on today’s top policy issues and the candidates running for office. And to close out the day, Maine Credit Union League President/CEO Todd Mason will interview a Special Guest to talk about why credit union advocacy and electing pro-credit union candidates matter. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

CNN Pundit Regales Scientific Assembly with Tales of Clinton, Bush, and Obama

EMERGENCY MEDICINE NEWS Exclusively for EMNow’s ACEP Scientific Assembly Edition: October 2009 CNN Pundit Regales Scientific Assembly with Tales of Clinton, Bush, and Obama By Lisa Hoffman thought of the book, he said, “It always helps when people misun- f you close your eyes when Paul Begala does his Bill Clinton derestimate me.” Iimpersonation, you might swear the former president was Barack Obama is another story, in the room. It’s an uncanny display that nails the Arkansas however, Mr. Begala said, and even drawl, the deliberate gestures, and the sincere facial expres- those who oppose him don’t deny sions. That characterization was learned at the knee, as it he is brilliant and politically adept. were, after Mr. Begala spent years as a key player in Clinton’s He has learned from others’ past inner circle. mistakes, and “it’s because we Mr. Begala proudly admits he’s a Democrat, and failed in ’93 and ‘94 that he’s likely Mr. Paul Begala although he now makes his living as a CNN political ana- to succeed. He’s put his whole lyst, no one would ever accuse him of representing any- political capital behind health care.” thing less than a liberal perspective. And he was there the Mr. Begala said the most remarkable thing about President first time around when health care reform ultimately went Obama is what he called his American exceptionalism. The down in flames in the early 1990s, its defeat in large part President himself said his story is unimaginable in any other due to his boss’s inflexibility, said Mr. -

The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2001 The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny Angela J. Davis American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Angela J., "The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny" (2001). Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals. 1397. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1397 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny AngelaJ. Davis' INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 395 I. DISCRETION, POWER, AND ABUSE ......................................................... 400 A. T-E INDF-ENDENT G E z I ETu aAD RESPO,\SE.................... -

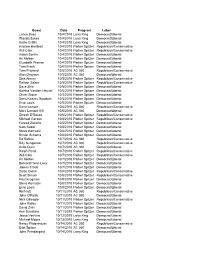

Guest Date Program Label Lance Bass 10/4/2010 Larry King

Guest Date Program Label Lance Bass 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Wanda Sykes 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Kathy Griffin 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Andrew Breitbart 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Will Cain 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Aaron Sorkin 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Ari Melber 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Elizabeth Warren 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Tom Frank 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Tom Prichard 10/5/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Alan Grayson 10/5/2010 AC 360 Democrat/Liberal Dick Armey 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Reihan Salam 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Dave Zirin 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Katrina Vanden Heuvel 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Oliver Stone 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Doris Kearns Goodwin 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Errol Louis 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Dana Loesch 10/6/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Marc Lamont Hill 10/6/2010 AC 360 Democrat/Liberal Dinesh D'Souza 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Michael Gerson 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Fareed Zakaria 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Sam Seder 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Steve Kornacki 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Simon Schama 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Ed Rollins 10/7/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Billy Nungesser 10/7/2010 -

This Is a Rush Transcript from “On the Record ,” March 6, 2009

This is a rush transcript from “On the Record ,” March 6, 2009. This copy may not be in its final form and may be updated. GRETA VAN SUSTEREN, FOX NEWS HOST: The brother of the alleged architect of the anti-Rush campaign is speaking out. To take you back, after talk show host Rush Limbaugh spoke at CPAC, GOP head Michael Steele called Rush an “entertainer,” and added that Rush’s remarks are “incendiary and ugly.” Rush quickly swung back, and Michael Steele quickly apologized. Then President Obama’s former campaign manager wrote an op-ed called “Minority leader Limbaugh.” And the DCCC launched a Web site called I’msorryRush.com, mocking Republicans who have insulted Rush and then immediately rushed to apologize to him. “Politico” says it is all part of a larger effort by big name Democrats like Paul Begala, James Carville, and even White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel to paint Rush Limbaugh as the face of the GOP. Now, Paul Begala’s brother Chris Begala, who is a media and political consultant and is a partner of Begala and McGrath is taking a stand. It’s nice to see you again, Chris. And, Chris, just to get things straight, are you the good Begala, or the bad Begala. CHRIS BEGALA, POLITICAL CONSULTANT: Well, you know, I am honored to be able to work with President Bush 41 and his office here in Houston. And many years ago he dubbed me “the good Begala.” So I wear that moniker proudly. VAN SUSTEREN: All right. I knew that. -

History Early History

Cable News Network, almost always referred to by its initialism CNN, is a U.S. cable newsnetwork founded in 1980 by Ted Turner.[1][2] Upon its launch, CNN was the first network to provide 24-hour television news coverage,[3] and the first all-news television network in the United States.[4]While the news network has numerous affiliates, CNN primarily broadcasts from its headquarters at the CNN Center in Atlanta, the Time Warner Center in New York City, and studios in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. CNN is owned by parent company Time Warner, and the U.S. news network is a division of the Turner Broadcasting System.[5] CNN is sometimes referred to as CNN/U.S. to distinguish the North American channel from its international counterpart, CNN International. As of June 2008, CNN is available in over 93 million U.S. households.[6] Broadcast coverage extends to over 890,000 American hotel rooms,[6] and the U.S broadcast is also shown in Canada. Globally, CNN programming airs through CNN International, which can be seen by viewers in over 212 countries and territories.[7] In terms of regular viewers (Nielsen ratings), CNN rates as the United States' number two cable news network and has the most unique viewers (Nielsen Cume Ratings).[8] History Early history CNN's first broadcast with David Walkerand Lois Hart on June 1, 1980. Main article: History of CNN: 1980-2003 The Cable News Network was launched at 5:00 p.m. EST on Sunday June 1, 1980. After an introduction by Ted Turner, the husband and wife team of David Walker and Lois Hart anchored the first newscast.[9] Since its debut, CNN has expanded its reach to a number of cable and satellite television networks, several web sites, specialized closed-circuit networks (such as CNN Airport Network), and a radio network. -

Office of the Chief of Staff, in Full

THE WHITE HOUSE TRANSITION PROJECT 1997-2021 Smoothing the Peaceful Transfer of Democratic Power Report 2021—20 THE OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF STAFF David B. Cohen, The University of Akron Charles E. Walcott, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University Smoothing the Peaceful Transfer of Democratic Power WHO WE ARE & WHAT WE DO THE WHITE HOUSE TRANSITION PROJECT. Begun in 1998, the White House Transition Project provides information about individual offices for staff coming into the White House to help streamline the process of transition from one administration to the next. A nonpartisan, nonprofit group, the WHTP brings together political science scholars who study the presidency and White House operations to write analytical pieces on relevant topics about presidential transitions, presidential appointments, and crisis management. Since its creation, it has participated in the 2001, 2005, 2009, 2013, 2017, and now the 2021. WHTP coordinates with government agencies and other non-profit groups, e.g., the US National Archives or the Partnership for Public Service. It also consults with foreign governments and organizations interested in improving governmental transitions, worldwide. See the project at http://whitehousetransitionproject.org The White House Transition Project produces a number of materials, including: . White House Office Essays: Based on interviews with key personnel who have borne these unique responsibilities, including former White House Chiefs of Staff; Staff Secretaries; Counsels; Press Secretaries, etc. , WHTP produces briefing books for each of the critical White House offices. These briefs compile the best practices suggested by those who have carried out the duties of these office. With the permission of the interviewees, interviews are available on the National Archives website page dedicated to this project: . -

Appendix C—Checklist of White House Press Releases

Appendix CÐChecklist of White House Press Releases The following list contains releases of the Office of Released January 13 the Press Secretary which are not included in this Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary Mike book. McCurry Released January 5 Statement by the Press Secretary: Official Visit by Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary Mike British Prime Minister Tony Blair McCurry Released January 14 Transcript of a press briefing by Office of Manage- Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary Mike ment and Budget Director Franklin Raines and Na- McCurry tional Economic Council Director Gene Sperling on the budget Statement by the Press Secretary on the President's confidence in Secretary of Labor Alexis Herman Statement by the Press Secretary: Visit by President Stoyanov of Bulgaria Statement by Counsel to the President Charles F.C. Ruff on Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr's inter- Released January 6 view of the First Lady Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary Mike McCurry Released January 15 Transcript of a press briefing by Health and Human Statement by the Press Secretary on the Presidential Services Secretary Donna Shalala, Labor Secretary Medal of Freedom recipients Alexis Herman, and National Economic Council Di- Statement by the Press Secretary: Agreement between rector Gene Sperling on proposed legislation on Medi- Indonesia and the IMF care Statement by the Press Secretary: China Nuclear Cer- Released January 7 tification Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary Mike -

The Constitutional Dilemma of Litigation Under the Independent Counsel System, 83 Minn

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 1999 The onsC titutional Dilemma of Litigation under the Independent Counsel System William K. Kelley Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation William K. Kelley, The Constitutional Dilemma of Litigation under the Independent Counsel System, 83 Minn. L. Rev. 1197 (1999). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/135 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Constitutional Dilemma of Litigation Under the Independent Counsel System William K. Kelleyt In this Article, I examine the most prominent institutional outgrowth of the Watergate era and the decision in United States v. Nixon:' the independent counsel system as established by the Ethics in Government Act of 1978.2 That system, which created the institution of the independent counsel, has produced a number of spectacles in American law. The principal example is the prominent role that Independent t Associate Professor of Law, University of Notre Dame. I have served as a consultant to Independent Counsel Kenneth W. Starr, including in some of the litigation discussed herein; the views reflected in this Article are, of course, only my own, and should not be taken as reflecting the views of the Office of Independent Counsel or any of its staff. I thank Rebecca Brown, John Manning, and Julie O'Sullivan for their gracious comments and collegial good cheer. -

LEGISLATIVE DAY March 13–15, 2016 | Washington, DC | Capital Hilton

LEGISLATIVE DAY March 13–15, 2016 | Washington, DC | Capital Hilton SPONSORED BY HOSTED BY or 29 years, pest management professionals have directly impacted federal public policy by visiting their Members of Congress at NPMA’s Legislative Day. In fact, Fit’s proven that in-person visits have the most impact on a Senator or Representative who is undecided on an issue. The fact is, nothing makes a bigger impression on your legislators than a visit from YOU. NPMA’s visits to Capitol Hill during Legislative Day this March will provide a tremendous opportunity to make an impression on your Members of Congress. Use this opportunity to establish a line of communication and develop a relationship with your Representative, Senators, and their staff. After all, they work for you. The reality is that no single voice carries more weight with your elected officials than your own. And, while NPMA provides the strength, the vision, and the infrastructure to move the industry forward in order to grow, the biggest part of this successful equation is you. This is your opportunity to make a difference. Capital Hilton, Washington, DC This year, Legislative Day will be held at the Capital the group rate of $283 per night (single/double). Hilton. To reserve your room, call (202) 393-1000 by After February 10, rooms and the group rate are February 10, 2016 and mention "NPMA" to receive subject to availability. SCHEDULE OF EVENTS SAT | MARCH 12 Meet Your Members of Congress Noon – 5:00 PM NPMA Board of When we receive your registration, we will contact your U.S.