Narrative Comedy Screenwriting: Facilitating Self-Directed, Transformative Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

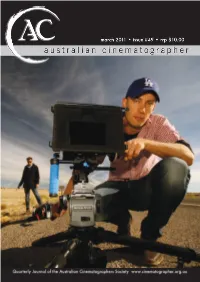

AC Issue49 March2011.Pdf

ac_issue#49.indd 1 22/03/11 2:14 PM Complete 35mm Package You thought you couldn’t afford film anymore... ...think again. Complete 35mm is the 35mm film and processing package from FUJIFILM / Awesome Support and Deluxe. Designed to offer the flexibility and logistical benefits of the film origination at a preferential price. The package includes: • 35mm FUJIFILM motion picture film stock • 35mm negative developing at Deluxe 400’ roll* 1000’ roll* $424 ex gst $1060 ex gst *This special package runs from 1st December 2010 to 31st January 2011 and it is open to TVC production companies for TVC / Rock clips / Web idents etc. Package applies to the complete range of FUJIFILM 35mm film in all speeds. No minimum or maximum order. Brought together by AUSTRALIA Contact: Ali Peck at Awesome Support 0411 871 521 [email protected] Jan Thornton at Deluxe Sydney (02) 9429 6500 [email protected] or Ebony Greaves at Deluxe Melbourne (03) 9528 6188 [email protected] ac_issue#49.indd 2 22/03/11 2:15 PM Not your average day at the supermarket. It’s Bait in 3D. Honestly, it would have been very difficult to make this movie without Panavision. Their investment and commitment to 3D technologies is a huge advantage to filmmakers. Without a company the size and stature of Panavision behind these projects they would be very difficult to achieve. Ross Emery ACS Shooting in 3D is a complex and challenging undertaking. It’s amazing how many people talk about being able to do it, but Panavision actually knows how to make it happen. -

Mel Buttle Life Lessons from School Heroin Bust Secret Jungle Operation

JULY 31-AUGUST 1, 2021 CHIP Mel Buttle Life lessons OFF from school Heroin bust Secret jungle operation THE BLOCK He’s been honing his axe skills since he could walk, now fifth-generation woodchopper Archie Head is eyeing Ekka glory JILL POULSEN FEEDBACK Upfront 28 William McInnes 3 Mel Buttle 3 Ordinary Person 15 You & Me 16 Features Class of their own 4 EDITOR’S NOTE Rock star return 8 Flight of fancy 12 There is plenty of anticipation 18 surrounding this year’s Ekka after it Life&Style became one of the many events of last year that were cancelled or reduced to Culture Club 19 small online affairs. The Cut 19 To welcome the country heroes back into the city, Jill Poulsen meets a few of Fashion 20 those hopeful of victory in three of the 44 Cafe 21 competition sections. Cover star Archie Recipe 22 Head, 9, will compete alongside his parents and two siblings. Reigning Ekka Dining 23 champions, the Iseppi family reveal their Travel 24 preparations ahead of the cattle exhibit, and cake decorator Malcolm Pratt, 73, Books 26 will celebrate his 50th year entering the Weddings 28 cookery section. Big Quiz 30 In these uncertain times, the return of the Ekka is something worth cheering. 21 My Life 31 Cover Archie Head Photography Lachie Millard Editor Natalie Gregg Deputy Editor Alison Walsh Arts Editor Phil Brown Design Sean Thomas Stage 1 Selling Now! At last…Luxury Retirement without leaving the Bayside. Marrying the expertise and vision of two of the most esteemed retirement and aged-care providers, the award-winning Village Retirement Group and Anglicare are thrilled to deliver the best retirement living to the Bay in decades! Call Kath on 3854 3737 to register your interest today! Visit our Information Centre, Tue-Sat 10am-4pm 162 Oceana Terrace, Manly thevillagemanly.com.au 02 QWEEKEND.COM.AU JULY 31-AUGUST 1, 2021 V0 - BCME01Z01QW MEL WILLIAM BUTTLE McINNES “The centre of any tuckshop pie, sausage roll In love with or lasagne will be lava. -

Archived at the Flinders Academic Commons

Archived at the Flinders Academic Commons: http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/ "This is an Author's Accepted Manuscript of an article published in Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, published online 12 March 2013. © Taylor & Francis, available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10304312.2 013.772110#.Ui0Jfcbdd8E“ Please cite this as: Erhart, J.G., 2013. ‘Your heart goes out to the Australian Tourist Board’: critical uncertainty and the management of censure in Chris Lilley's TV comedies. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, DOI:10.1080/10304312.2013.772110 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2013.772110 © 2013 Taylor & Francis. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ‘Your Heart Goes Out to the Australian Tourist Board’: critical uncertainty and the management of censure in Chris Lilley’s TV Comedies Since the year 2005 when We Can Be Heroes: Finding the Australian of the Year first appeared on TV, Chris Lilley’s name has been associated with controversy in the Australian and international press. Making fun of disabled and gay people, drug overdose victims, and rape survivors, are but a few of the accusations which have been levied. While some of the uproar has been due to factors beyond Lilley’s control (the notorious coincidence of a real- life overdose with Lilley’s representation -

Kitty Flanagan

KITTY FLANAGAN Ever stood under glaring lights recounting your hopes, dreams, fears and most embarrassing moments to a room full of strangers in a desperate attempt to keep them entertained? Welcome to the terrifying world of stand up, which Kitty Flanagan has spent the past 20 years successfully navigating, proving herself as not only one of Australia’s best, but also most beloved comedians. Since first gracing Australian TV screens in ‘Full Frontal’ during the 90s, Kitty has appeared in numerous productions, performing regularly at comedy venues around Australia and internationally, and appearing on The Project, Have You Been Paying Attention, The Weekly and Utopia. Amanda meets up with Kitty to learn what life’s like under the spotlight (literally), discuss her new book, ‘Bridge Burning And Other Hobbies’, and discover more about this (inaccurately) self described ‘wallflower’. HELLO KITTY After attending Catholic school and developing a healthy disrespect for institutionalised religion, Kitty headed to university where she enjoyed studying a wide range of subjects, none of which had any relation to her current occupation. Once compulsory fee paying was introduced, Kitty flew the tertiary coop, bluffing her way into advertising and working as a copywriter. After her desperate attempts to get fired finally paid off, Kitty began pouring pints, working as a bartender at the Harold Park Hotel, which incidentally happened to run an open mic night. With a backlog of anecdotes and an inexplicable need to vent her deepest, darkest secrets in front of a room full of beer-swilling old men, Kitty spent nights honing her skills, quickly becoming a pub favourite. -

30 Years of Awgie Award Winners

AWG SPECIAL AWARD WINNERS 1973 - 2019 Special Awards The Dorothy Crawford Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Profession and the Industry The Fred Parsons Award for Outstanding Contribution to Australian Comedy The Richard Lane Award for Outstanding Service and Dedication to the Australian Writers' Guild The Hector Crawford Award For Outstanding Contribution to the Craft as a Script Producer, Editor or Dramaturg Australian Writers’ Guild Lifetime Achievement Award, proudly presented by Foxtel David Williamson Prize - Given in Celebration and Recognition of Excellence in Writing for Australian Theatre AWG Awards Monte Miller Award 1972 to 2006 Monte Miller Award - Long Form Monte Miller Award - Short Form John Hinde Award for Excellence in Science-Fiction Writing Life Membership Life Members Previous Awards Foxtel Fellowship - In Recognition of a Significant and Impressive Body of Work (2007-2014) Kit Denton Fellowship For Courage and Excellence in Performance Writing (2007-2012) CAL Peer Recognition Prize - Awarded to Major AWGIE Winner (2008-2010) Richard Wherrett Prize - Recognising Excellence in Australian Playwriting (2007-2009) Ian Reed Award for Best Script by a First-Time Radio Writer (1998-2000) Australian Writers' Foundation Playwriting Award (2014-2015) The Dorothy Crawford Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Profession and the Industry Previously The Dorothy Crawford Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Profession (1984-2018) 1984 Carmel Powers 1985 Katherine Brisbane 1986 Betty Burstall 1987 Hector Crawford -

576 the Contemporary Pacific • 27:2 (2015) Vilsoni Hereniko *

576 the contemporary pacific • 27:2 (2015) Wild felt familiar. I had experienced film, disguised as an ordinary road the same feelings in countless other movie. As such, it is a film that is easy mainstream movies. In The Pā Boys, to overlook, even at film festivals however, my emotional responses where it might be possible to discover emanated from the deep recesses of a fearlessly independent voice. my being, which very few films have When you accidentally stumble been able to touch. Rotumans call this on an authentic voice, like I did, you place huga, which literally translates know you’ve finally experienced as “inside of the body, esp. of the the film you have always hoped to abdomen”; Hawaiians call it the na‘au see when you go to the movies but while Māori call it the ngakau. thought the day would never come! It is in one’s gut that the truth of This was how it was with me. the ages resides. This kind of knowing vilsoni hereniko cannot be explained logically or ratio- University of Hawai‘i, nally. It is a knowing that is activated Mānoa when one experiences a universal truth, which in The Pā Boys, is this: *** For these Māori young people to be truly healed, they needed to reconnect Jonah From Tonga. 2014. Televi- with and learn about their ances- sion series, 180 minutes, dvd, color, tral pasts in order to become more in English. Written by Chris Lilley, humane, more compassionate, better produced by Chris Lilley and Laura human beings. This is the universal Waters, and directed by Chris Lilley message, told not through a sermon and Stuart McDonald; distributed but through a musical story about by hbo. -

Pocket Product Guide 2006

THENew Digital Platform MIPTV 2012 tm MIPTV POCKET ISSUE & PRODUCT OFFILMGUIDE New One Stop Product Guide Search at the Markets Paperless - Weightless - Green Read the Synopsis - Watch the Trailer BUSINESSC onnect to Seller - Buy Product MIPTVDaily Editions April 1-4, 2012 - Unabridged MIPTV Product Guide + Stills Cher Ami - Magus Entertainment - Booth 12.32 POD 32 (Mountain Road) STEP UP to 21st Century The DIGITAL Platform PUBLISHING Is The FUTURE MIPTV PRODUCT GUIDE 2012 Mountain, Nature, Extreme, Geography, 10 FRANCS Water, Surprising 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, Delivery Status: Screening France 75019 France, Tel: Year of Production: 2011 Country of +33.1.487.44.377. Fax: +33.1.487.48.265. Origin: Slovakia http://www.10francs.f - email: Only the best of the best are able to abseil [email protected] into depths The Iron Hole, but even that Distributor doesn't guarantee that they will ever man- At MIPTV: Yohann Cornu (Sales age to get back.That's up to nature to Executive), Christelle Quillévéré (Sales) decide. Office: MEDIA Stand N°H4.35, Tel: + GOOD MORNING LENIN ! 33.6.628.04.377. Fax: + 33.1.487.48.265 Documentary (50') BEING KOSHER Language: English, Polish Documentary (52' & 92') Director: Konrad Szolajski Language: German, English Producer: ZK Studio Ltd Director: Ruth Olsman Key Cast: Surprising, Travel, History, Producer: Indi Film Gmbh Human Stories, Daily Life, Humour, Key Cast: Surprising, Judaism, Religion, Politics, Business, Europe, Ethnology Tradition, Culture, Daily life, Education, Delivery Status: Screening Ethnology, Humour, Interviews Year of Production: 2010 Country of Delivery Status: Screening Origin: Poland Year of Production: 2010 Country of Western foreigners come to Poland to expe- Origin: Germany rience life under communism enacted by A tragicomic exploration of Jewish purity former steel mill workers who, in this way, laws ! From kosher food to ritual hygiene, escaped unemployment. -

CHICAGO to Tour Australia in 2009 with a Stellar Cast

MEDIA RELEASE Embargoed until 6pm November 12, 2008 We had it coming…CHICAGO to tour Australia in 2009 with a stellar cast Australia, prepare yourself for the razzle-dazzle of the hit musical Chicago, set to tour nationally throughout 2009 following a Gala Opening at Brisbane‟s Lyric Theatre, QPAC. Winner of six Tony Awards®, two Olivier Awards, a Grammy® and thousands of standing ovations, Chicago is Broadway‟s longest-running Musical Revival and the longest running American Musical every to play the West End. It is nearly a decade since the “story of murder, greed, corruption, violence, exploitation, adultery and treachery” played in Australia. Known for its sizzling score and sensational choreography, Chicago is the story of a nightclub dancer, a smooth talking lawyer and a cell block of sin and merry murderesses. Producer John Frost today announced his stellar cast: Caroline O’Connor as Velma Kelly, Sharon Millerchip as Roxie Hart, Craig McLachlan as Billy Flynn, and Gina Riley as Matron “Mama” Morton. “I‟m thrilled to bring back to the Australian stage this wonderful musical, especially with the extraordinary cast we have assembled. Velma Kelly is the role which took Caroline O‟Connor to Broadway for the first time, and her legion of fans will, I‟m sure, be overjoyed to see her perform it once again. Sharon Millerchip has previously played Velma in Chicago ten years ago, and since has won awards for her many musical theatre roles. She will be an astonishing Roxie. Craig McLachlan blew us all away with his incredible audition, and he‟s going to astound people with his talent as a musical theatre performer. -

2019 AACTA AWARDS PRESENTED by FOXTEL All Nominees – by Category FEATURE FILM

2019 AACTA AWARDS PRESENTED BY FOXTEL All Nominees – by Category FEATURE FILM AACTA AWARD FOR BEST FILM PRESENTED BY FOXTEL HOTEL MUMBAI Basil Iwanyk, Gary Hamilton, Julie Ryan, Jomon Thomas – Hotel Mumbai Double Guess Productions JUDY & PUNCH Michele Bennett, Nash Edgerton, Danny Gabai – Vice Media LLC, Blue-Tongue Films, Pariah Productions THE KING Brad Pitt, Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, Liz Watts, David Michôd, Joel Edgerton – Plan B Entertainment, Porchlight Films, A Yoki Inc, Blue-Tongue Films THE NIGHTINGALE Kristina Ceyton, Bruna Papandrea, Steve Hutensky, Jennifer Kent – Causeway Films, Made Up Stories RIDE LIKE A GIRL Richard Keddie, Rachel Griffiths, Susie Montague – The Film Company, Magdalene Media TOP END WEDDING Rosemary Blight, Kylie du Fresne, Kate Croser – Goalpost Pictures AACTA AWARD FOR BEST INDIE FILM PRESENTED BY EVENT CINEMAS ACUTE MISFORTUNE Thomas M. Wright, Virginia Kay, Jamie Houge, Liz Kearney – Arenamedia, Plot Media, Blackheath Films BOOK WEEK Heath Davis, Joanne Weatherstone – Crash House Productions BUOYANCY Rodd Rathjen, Samantha Jennings, Kristina Ceyton, Rita Walsh – Causeway Films EMU RUNNER Imogen Thomas, Victor Evatt, Antonia Barnard, John Fink – Emu Runner Film SEQUIN IN A BLUE ROOM Samuel Van Grinsven, Sophie Hattch, Linus Gibson AACTA AWARD FOR BEST DIRECTION HOTEL MUMBAI Anthony Maras – Hotel Mumbai Double Guess Productions JUDY & PUNCH Mirrah Foulkes – Vice Media LLC, Blue-Tongue Films, Pariah Productions THE KING David Michôd – Plan B Entertainment, Porchlight Films, A Yoki Inc, -

Upper Middle Bogan Med

When an upper middle class woman discovers she is adopted she is shocked to find out... She comes from a drag racing family in the outer suburbs. Synopsis Upper Middle Bogan is a new eight-part comedy series Heading up a drag racing team in the outer suburbs, which tells the story of two families living at opposite Wayne and Julie are thrilled to be reunited with the ends of the freeway. daughter they thought they had lost. Sensing she was different her whole life, Bess Denyar Bess is keen to get to know her new family, however (Annie Maynard), a doctor with a highbrow mother, fitting in doesn’t always come easily. Her sister is a Margaret (Robyn Nevin), an architect husband, Danny tough nut to crack and there are misunderstandings (Patrick Brammall) and twin 13 year olds at a private aplenty. Navigating their way through the unknown is school, finds out she is adopted and is stunned. Even a challenge for all of these very entertaining individuals. more so when she meets her birth parents, Wayne (Glenn Robbins) and Julie Wheeler (Robyn Malcolm). A Gristmill Production for ABC TV. Executive Producers Robyn Butler, Wayne Hope, Geoff Porz and ABC TV If that’s not enough to digest, Bess also discovers she Executive Producer Debbie Lee. has siblings, Amber (Michala Banas), Kayne (Rhys Mitchell) and Brianna (Madeleine Jevic). PREMIERES THURSDAY 15 AUGUST 8.30PM ABC1 For more information, we’d be happy to help. Tracey Taylor, ABC TVMarComs P. 03 9524 2313 M. 0419 528 213 E. [email protected] For images visit abc.net.au/tvpublicity abc.net.au/abc1 facebook.com/abctv twitter.com/abctv #uppermiddlebogan One Two I’m A Swan Forefathers, Two Mothers THURSDAY 15 AUGUST 8.30PM ABC1 THURSDAY 22 AUGUST 8.30PM ABC1 When Bess Denyar, a successful doctor with an Still struggling with the news she is adopted, Bess architect husband, an overbearing mother and is angry with Margaret for lying to her for all these twin 13 year olds at a private school, finds out years and refuses to speak to her. -

The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart by Holly Ringland

FREE APRIL 2018 The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart by Holly Ringland Read our review on page 8 Growing Up Aboriginal in Australia edited by Anita Heiss Read an extract on page 7 BOOKS MUSIC FILM EVENTS GURRUMUL page 22 BLUE PLANET II JAMILA RIZVI ROBERT HOLLY ANITA HEISS page 21 page 4 HILLMAN RINGLAND page 13 page 8 page 8 CARLTON 309 LYGON ST 9347 6633 KIDS 315 LYGON ST 9341 7730 DONCASTER WESTFIELD DONCASTER, 619 DONCASTER RD 9810 0891 HAWTHORN 701 GLENFERRIE RD 9819 1917 MALVERN 185 GLENFERRIE RD 9509 1952 ST KILDA 112 ACLAND ST 9525 3852 STATE LIBRARY VICTORIA 328 SWANSTON ST 8664 7540 | SEE SHOP OPENING HOURS, BROWSE AND BUY ONLINE AT WWW.READINGS.COM.AU READINGS MONTHLY 3 April 2018 goers can discover the largest collection of April rare, out-of-print and collectable books in The Women’s Prize for Fiction 2018 longlist 25% off a range of Insight & Berlitz travel Australia, go inside heritage buildings, listen The longlist for the Women’s Prize for guides to live music, watch street performers, try Fiction 2018 has been announced. This Throughout April, we’re offering 25% off News their hand in a Scrabble tournament and prize celebrates the best writing from female a select range of Insight & Berlitz travel visit the Readings bookstall at the Festival. authors around the world. This year’s longlist guides. This offer is exclusively available A weekend pass is $10 for adults, and $5 for includes: H(a)ppy by Nicola Barker; The Idiot at our Carlton and Hawthorn stores secondary school students and children.