Interview with Gary Leib # VRK-A-L-2010-044 Interview # 1: October 5, 2010 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F9f Panther Units of the Korean War

0413&:$0.#"5"*3$3"'5t F9F PANTHER UNITS OF THE KOREAN WAR Warren Thompson © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com SERIES EDITOR: TONY HOLMES OSPREY COMBAT AIRCRAFT 103 F9F PANTHER UNITS OF THE KOREAN WAR WARREN THOMPSON © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE US NAVY PANTHERS STRIKE EARLY 6 CHAPTER TWO THE WAR DRAGS ON 18 CHAPTER THREE MORE MISSIONS AND MORE MiGS 50 CHAPTER FOUR INTERDICTION, RESCAP, CAS AND MORE MiGS 60 CHAPTER FIVE MARINE PANTHERS ENTER THE WAR 72 APPENDICES 87 COLOUR PLATES COMMENTARY 89 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com US NAVY PANTHERS CHAPTER ONE STRIKE EARLY he United States’ brief period of post-World War 2 peace T and economic recovery was abruptly shattered on the morning of 25 June 1950 when troops from the communist state of North Korea crossed the 38th Parallel and invaded their neighbour to the south. American military power in the Far East had by then been reduced to a token force that was ill equipped to oppose the Soviet-backed North Korean military. The United States Air Force (USAF), which had been in the process of moving to an all-jet force in the region, responded immediately with what it had in Japan and Okinawa. The biggest problem for the USAF, however, was that its F-80 Shooting Star fighter-bombers lacked the range to hit North Korean targets, and their loiter time over enemy columns already in South Korea was severely restricted. This pointed to the need for the US Navy to bolster American air power in the region by deploying its aircraft carriers to the region. -

Another Example of a Mission Ready Ship Because of a U.S. Navy Port Engineer

Another example of a mission ready ship because of a U.S. Navy Port Engineer USS Boxer ARG completes amphibious landing drill in Djibouti on the Horn of Africa https://navaltoday.com/2019/08/28/boxer-arg-completes-amphibious-landing-drill-in-djibouti/ Boxer ARG is comprised of amphibious assault ship USS Boxer (LHD 4), amphibious transport dock USS John P Murtha (LPD 26), and amphibious dock landing ship USS Harpers Ferry (LSD 49). Amphibious assault vehicles (AAVs) from the 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) descended on Djibouti’s Arta Beach after departing the well deck of the amphibious dock landing ship USS Harpers Ferry (LSD 49) during an exercise to seize a fictional enemy objective. Maj. Victor Garcia, India Co., Battalion Landing Team (BLT) 3/5 company commander, explained that amphibious assaults are one of the MEU’s primary missions; a capability that makes the MEU one of the most lethal and responsive crisis response forces in the US defense department arsenal. Amphibious assault vehicles are one of the oldest and most reliable platforms in the Marine Corps. AAVs, or “tracks,” are essentially floating tanks that can seize or secure a beach head and enable more forces to flow ashore in the event of combat operations. The group is deployed to the US 5th Fleet area of operations in support of naval operations to ensure maritime stability and security in the Central Region, connecting the Mediterranean and the Pacific through the Western Indian Ocean and three strategic choke points. Webmaster’s Note: USS Boxer (LHD-4) is a Wasp-class amphibious assault ship of the United States Navy. -

T Vietnam Service Report

Honoring Our Vietnam War and Vietnam Era Veterans February 28, 1961 - May 7, 1975 Town of West Seneca, New York Name: TYCZKA Hometown: WEST SENECA EDWARD A. Address: BOSSE LANE Vietnam Era Vietnam War Veteran Year Entered: 1961 Service Branch:MARINE CORPS. Rank: SGT Year Discharged: 1966 Unit / Squadron: 3RD BATTALION, 8TH MARINES USS BOXER (LPH-4) Medals / Citations: GOOD CONDUCT MEDAL ARMED FORCES EXPEDITIONARY MEDAL NATIONAL DEFENSE SERVICE RIBBON Served in War Zone Theater of Operations / Assignment: Service Notes: Sergeant (E-5) Edward A. Tyczka was stationed on the aircraft carrier, the USS Boxer, in the Caribbean Sea off the Cuban coast during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 Base Assignments: Camp Lejeune, North Carolina - Located in Jacksonville, North Carolina, construction on Camp Lejeune was begun in 1941 and named in honor of the 13th Commandant of the Marine Corps, John A. Lejeune / As a military training facility, the Camp's 14 miles of beaches make it a major area for amphibious assault training, and its location between two deep-water ports (Wilmington and Morehead City) allows for fast deployments Clarksville Base, Tennessee - Built in 1942 and operated by the U.S. Navy from 1948 through 1969, Clarksville Base was a heavily-guarded Cold War secret / The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) built more than 240 buildings and logistic structures within Fort Campbell for the sole purpose of transporting, storing and assembling the nation’s fast-growing stockpile of nuclear weapons / At one time, one-third of America's nuclear -

Columbia Filmcolumbia Is Grateful to the Following Sponsors for Their Generous Support

O C T O B E R 1 8 – 2 7 , 2 0 1 9 20 TH ANNIVERSARY FILM COLUMBIA FILMCOLUMBIA IS GRATEFUL TO THE FOLLOWING SPONSORS FOR THEIR GENEROUS SUPPORT BENEFACTOR EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 20 TH PRODUCERS FILM COLUMBIA FESTIVAL SPONSORS MEDIA PARTNERS OCTOBER 18–27, 2019 | CHATHAM, NEW YORK Programs of the Crandell Theatre are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the New York filmcolumbia.org State Legislature. 5 VENUES AND SCHEDULE 9 CRANDELL THEATRE VENUES AND SCHEDULE 11 20th FILMCOLUMBIA CRANDELL THEATRE 48 Main Street, Chatham 13 THE FILMS á Friday, October 18 56 PERSONNEL 1:00pm ADAM (page 15) 56 DONORS 4:00pm THE ICE STORM (page 15) á Saturday, October 19 74 ORDER TICKETS 12:00 noon DRIVEWAYS (page 16) 2:30pm CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON (page 17) á Sunday, October 20 11:00am QUEEN OF HEARTS: AUDREY FLACK (page 18) 1:00pm GIVE ME LIBERTY (page 18 3:30pm THE VAST OF NIGHT (page 19) 5:30pm ZOMBI CHILD (page 19) 7:30pm FRANKIE + DESIGN IN MIND: ON LOCATION WITH JAMES IVORY (short) (page 20) á Monday, October 21 11:30am THE TROUBLE WITH YOU (page 21) 1:30pm SYNONYMS (page 21) 4:00pm VARDA BY AGNÈS (page 22) 6:30pm SORRY WE MISSED YOU (page 22) 8:30pm PARASITE (page 23) á Tuesday, October 22 12:00 noon ICE ON FIRE (page 24) 2:00pm SOUTH MOUNTAIN (page 24) 4:00pm CUNNINGHAM (page 25) 6:00pm THE CHAMBERMAID (page 26) 8:15pm THE SONG OF NAMES (page 27) á Wednesday, October 23 11:30am SEW THE WINTER TO MY SKIN (page 28) 2:00pm MICKEY AND THE BEAR (page 28) 3:45pm CLEMENCY (page 29) 6:00pm -

2010 Program

FESTIVAL PASS $40 (DCAS members/seniors and students), $50 (general public) Note: A festival pass does not guarantee entry into a screening. Please arrive 15 minutes prior to a screening to ensure entry. PASSES & TICKETS SINGLE SCREENING ADMISSION The Dawson City International Short Film Festival is presented by the $6 (DCAS members/seniors & students), $7 (general public) KLONDIKE INSTITUTE OF ART AND CULTURE. We gratefully acknowledge the support of KIAC’s funding agencies and partners for making this possible. DCAS (Dawson City Arts Society) membership: $15 For further information on KIAC and its programs, All events take place at The Odd Fellows Hall, please visit our website at www.kiac.ca 2nd & Princess unless otherwise noted. www.dawsonfilmfest.com Festival Producer: Dan Sokolowski Programming: Dan Sokolowski, Kerry Barber, Tara Rudnickas Projectionists: Florian Boulais, Megan Graham, Aaron Burnie Executive Director: Karen DuBois Front of House Manager: Karen MacKay Programs Manager: Tara Rudnickas Concession Manager: Georgia Fraser Programs Coordinator: Jenna Roebuck Cover and Poster Artworks: Veronica Verkley Administrative Assistant: Kerry Barber Program Design: Dan Sokolowski Gallery Director: Lance Blomgren Festival Committee Klondike Institute of Art and Culture Lulu Keating: Chair, Florian Boulais, Gail Calder, Suzanne Crocker, Box 8000, Dawson City, Yukon Y0B 1G0 Canada Stephanie Davidson, Kit Hepburn, Bill Kendrick, Gord MacRae, tel: 867 993 5005 Daisyanne Maguire, John Overell, Evelyn Pollock, Meg Walker fax: 867 993 5838 [email protected] www.kiac.ca 2010 DAWSON CITY INTERNATIONAL SHORT FILM FESTIVAL 1 ALL SCREENINGS and EVENTS in the ODD FELLOWS HALL BALLROOM unless otherwise noted. Thursday, 7 pm — Thursday, 9:30 pm Feature film by artists in residence Stefan Popescu and Katherine Berger. -

A Brief Education on Indigenous History

Phillipe & Jorge’s Cool, Cool World: Stuff of Legends: A brief education on Indigenous history Me Tarzan A local athlete you might not have heard of (outside his community) is Ellison Brown, born on the Narragansett Reservation in 1914. A mind-boggling distance runner, Brown was known publicly as “Tarzan,” although members of the tribe called him “Deerfoot.” Tarzan won the 1936 and 1939 Boston Marathons, and was on the historic 1936 US Olympic team that competed in Berlin, but was unable to race due to an injury. But to his credit, reports were that injury didn’t keep him from getting into a fight with some of Adolf Hitler’s Nazis at a local beer garden. A stonemason and shellfisherman, Brown ran distance races barefoot, and if you’re an avowed masochist, try that on for size. He would also disappear into the South County woods for days at a time, getting back to nature in his own way. He overcame a great deal of racism, and according to reports, once said he had to get his hair cut in New London because the barber in Westerly wouldn’t do it. Tarzan Brown has long been a legend in South County and deservedly so. And his duel with the Boston running star John Kelley in the 1936 Marathon, which Tarzan won, led to the christening of “Heartbreak Hill” toward the end of the 26+ miles. (see Fest at motifri.com/TarzanBrown) Mayflower P & J live in The Biggest Little by choice, which we hope is true of all residents. -

![Mon Sept 27 | 8:30 Pm Jack H. Skirball Series $9 [Students $7, Calarts $5]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6010/mon-sept-27-8-30-pm-jack-h-skirball-series-9-students-7-calarts-5-1046010.webp)

Mon Sept 27 | 8:30 Pm Jack H. Skirball Series $9 [Students $7, Calarts $5]

FILM AT REDCAT PRESENTS Mon Sept 27 | 8:30 pm Jack H. Skirball Series $9 [students $7, CalArts $5] THE BEST OF OTTAWA 2009 This selection of 12 outstanding films from the Ottawa International Animation Festival 2009, most of which are Los Angeles premieres, reflects the vitality of experimental animation today and includes work from Canada, England, Estonia, France, Germany, Poland, and the United States. Each filmmaker demonstrates a passion for telling stories, whether abstract or figurative, and the works showcase the rich possibilities of animation as personal art. Films include Eric Dyer’s mesmerizing The Bellow’s March, Diego Maclean’s haunting The Art of Drowning, and David OReilly’s sci-fi drama Please Say Something, as well as works by Jake Armstrong, Bastien Dubois, Julian Grey, Rao Heidmets, Stephen Irwin, Gary Leib, Ian Miller, Marv Newland, and Michal Socha. Two new films by American animators who continue to delight, disturb, and enlighten— Myth Labs by Martha Colburn and Presentation Theme by Jim Trainor—will also be screened. In person: Suzan Pitt, Ottawa International Animation Festival jury member “Martha Colburn’s animations charge the frame with such ferocity that it almost hurts to watch… Tacitly these unconscious imaginings give rise to strikingly clear associations, which is why the work is so illuminating—not just for its ideational and aesthetic lushness but for its approach.” – Dena Beard, Berkeley Art museum/Pacific Film Archive Program (TRT 81 min.) Julian Grey: OIAF 2009 Signal Film Head Gear Animation | Canada | 2009 | 0:45 The bouncing ball leads the audience to the 2009 edition of the Ottawa International Animation Festival. -

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

Jordan Family Papers, 1941-2009 SCHS# 0601.00 Description: .25 Linear Feet (1 Box) Background / Biographical Note: Correspondenc

Jordan Family Papers, 1941-2009 SCHS# 0601.00 Description: .25 linear feet (1 box) Background / Biographical Note: Correspondence, articles, and documents pertaining to the Jordan family. Three sons from this family- Nathan H. Jordan, Jr., Richard Jordan, and William Jordan- fought in World War II. The majority of the material relates to Nathan Haynes Jordan, Jr. (1918-1944), who joined the army in February 1942, trained at Camp Wheeler, Georgia for two years, sailed for the UK in July, 1944, and was deployed to France as a staff sergeant in Company M, 38th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Division, U.S. Army. He was listed as Missing in Action on August 14, 1944 during fighting near Tinchebray, France, after being severely wounded. Over a year later, on August 15, 1945, he was officially declared dead after the discovery of his remains. With the news of his death came an extensive correspondence in the late 1940s between his parents and the Department of the Army to ascertain what happened to him, locate his burial site (Plot E, Row 10, Grave 14) at the Brittany American Cemetery and Memorial in St. James, France, and determine whether he had a will. In the end, the government was unable to locate a will, and returned to his family only the single British coin and pencil that had been found on his body- his “personal effects”. For his sacrifice, Nathan was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart on September 8th, 1945. Nathan’s two brothers also had notable military careers. The oldest, Richard Holmes Jordan (1917-1963), joined the U.S. -

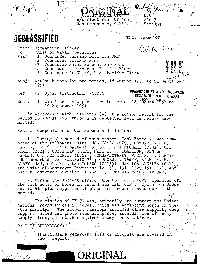

C-Jfkl? 2% To: Chief of It'aval Operations

- From: Commanding Officer' C-Jfkl? 2% To: Chief of It'aval Operations . Vid: (1)Comxnder Carrier Division GIG3 (2) Commander aZVdiu'TH Fleet (3) Comndnder Lava1 Forces, Far Zast (4) Comnander Air Forces, Pacific Fleet (5) Corxiander in Chief, U.3. Pacific Fleet 52 Subj: Action heport for the period, 18 liusust 1951 to 21 September 1951 kef: (a) Opfu'av Instruction 3480.4 bOWNGRAbED AT 3 YEAR tNJ"A&' OECtASSIFlED AFTER 12 YEARS Encl: CVG 5 Action-neport for the period 18 Xugu&!f!DOD 1 $&f3 1 to / (1) I 19 September 1951 % 1. In accordace with reference (a), the action report for the- period 18 ++usust 1951 throurh 19 aeptember 1951 is hereby sub- mitted: PAhT I Composition of Om Forces and Ilission: 1. During the period of this repor Task Force 77 wiis com- Y posed of the followirg units: U55 SSbEii cv9 COIiC;imIV 9 nn&; J. PLhkrcY, UaN embarked: USs 3ON FiIcI-Lm w313 : us; GCIXjIi (CV21) : OiXAXliV TFhL2, kAiUi TOHLIaOX, UbN errl- barked: Us2 1; JZRdY (5152 , COT,.S3JjX LT9 VADX H* i.1. iIARTIK2n US?, embdrked; Uaa HzLdKi(C~75); cOi;CIiUDIV TEXd3, hAIJf.1. 3. L. I,13Tf, JaH, embarked: Uaa 'EL390 (C~133): Us3 LO3 XKG3LJS (CA135) and units of Jestroyer Divisions 12, 51,. 13 1329 151, 171, and Lscort Destroyer Division 11 and 21. OT'C w CGr.'X-G-ijlIVONE - 2. During the subject period, the USS ~a,53~(CVS) operated off the eat COdSt of i.orea in accordance with CTF 77 Operation order fio. 22-51, plus supplemental plas 2nd orders issued during the period . -

USS Essex (CV 9) 18 Jul-4 Sep 1952

IECLASSIFIED DOWNGRADED AT 3 YEAR INTERVALS:. From: Commanding Officer DfCL;.SSIFIED AFTER 12 YEARS DOD DlR To: Chief of Naval Operations 5200.10 Via: (1) Commander Carrier Division THREE (2) Commander SEVENTH Fleet (3) Commander Naval Forces, Far East (4) Commander in Chief, u. s. Pacific Fleet Subj: Action Report for the Period 18 July 1952 to 4 September 1952 Ref: (a) O{Nav ln~etaion 3400.4 Encl: (1) Air Task Group TWO Action~Report, 18 July 1952 to 4 September 1952 1. In accordance with reference (a), the action report for the period 18 July 1952 to 4 September 1952 is hereby submitted. PART I OOMroSITION OF OWN FORCES AND MISSION. _ -~·- _D~g th!_I>,!z.:i<?<! ~2_6_.,I¥J:y __ :L~~2, USS ESSEX (CV9) was a unit of -s-pecial Task Group 50_.8. This group was composed of the following units.: USS ESSEX (CV9), CTG 50.8 and CanCarDivTHREE, RADM A. SOUCEK, USN, embarked, USS PHILIPPINE SEA (CV47) and screening units. b. During the above period USS ESSEX (CV9) operated in the South China Sea, the Formosa Strait and off the East Coast of Formosa in accordance with ComSEVEN'niFlt Operations Plan 75-52 and, CanCarDivTHREE Operations Order 1-52. ( The mission of TG 50.8 was to make a show of force off the China Coast 1 as a deterrent to Communist Chinese agressive actions against Formosa and to bolster the morale of Nationalist Chinese Forces on Formosa in support of United ( \Nations Poli~ on Formosa. c. During the period 27 July-4 September, USS ESSEX (CV9) was a unit of Task Force 77 at various times composed of the following units: USS ESSEX (CV9), ComCarDiv'lHREE, RADM A.