Geographical Variation in Argentine Ant Aggression Behaviour Mediated by Environmentally Derived Nestmate Recognition Cues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Aspects About Supella Longipalpa (Blattaria: Blattellidae)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2016; 6(12): 1065–1075 1065 HOSTED BY Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apjtb Review article http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2016.08.017 New aspects about Supella longipalpa (Blattaria: Blattellidae) Hassan Nasirian* Department of Medical Entomology and Vector Control, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The brown-banded cockroach, Supella longipalpa (Blattaria: Blattellidae) (S. longipalpa), Received 16 Jun 2015 recently has infested the buildings and hospitals in wide areas of Iran, and this review was Received in revised form 3 Jul 2015, prepared to identify current knowledge and knowledge gaps about the brown-banded 2nd revised form 7 Jun, 3rd revised cockroach. Scientific reports and peer-reviewed papers concerning S. longipalpa and form 18 Jul 2016 relevant topics were collected and synthesized with the objective of learning more about Accepted 10 Aug 2016 health-related impacts and possible management of S. longipalpa in Iran. Like the Available online 15 Oct 2016 German cockroach, the brown-banded cockroach is a known vector for food-borne dis- eases and drug resistant bacteria, contaminated by infectious disease agents, involved in human intestinal parasites and is the intermediate host of Trichospirura leptostoma and Keywords: Moniliformis moniliformis. Because its habitat is widespread, distributed throughout Brown-banded cockroach different areas of homes and buildings, it is difficult to control. -

Genetically Modified Baculoviruses for Pest

INSECT CONTROL BIOLOGICAL AND SYNTHETIC AGENTS This page intentionally left blank INSECT CONTROL BIOLOGICAL AND SYNTHETIC AGENTS EDITED BY LAWRENCE I. GILBERT SARJEET S. GILL Amsterdam • Boston • Heidelberg • London • New York • Oxford Paris • San Diego • San Francisco • Singapore • Sydney • Tokyo Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier Academic Press, 32 Jamestown Road, London, NW1 7BU, UK 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA 525 B Street, Suite 1800, San Diego, CA 92101-4495, USA ª 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved The chapters first appeared in Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science, edited by Lawrence I. Gilbert, Kostas Iatrou, and Sarjeet S. Gill (Elsevier, B.V. 2005). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone (þ44) 1865 843830, fax (þ44) 1865 853333, e-mail [email protected]. Requests may also be completed on-line via the homepage (http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissions). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Insect control : biological and synthetic agents / editors-in-chief: Lawrence I. Gilbert, Sarjeet S. Gill. – 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-12-381449-4 (alk. paper) 1. Insect pests–Control. 2. Insecticides. I. Gilbert, Lawrence I. (Lawrence Irwin), 1929- II. Gill, Sarjeet S. SB931.I42 2010 632’.7–dc22 2010010547 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-0-12-381449-4 Cover Images: (Top Left) Important pest insect targeted by neonicotinoid insecticides: Sweet-potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci; (Top Right) Control (bottom) and tebufenozide intoxicated by ingestion (top) larvae of the white tussock moth, from Chapter 4; (Bottom) Mode of action of Cry1A toxins, from Addendum A7. -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

A Dichotomous Key for the Identification of the Cockroach Fauna (Insecta: Blattaria) of Florida

Species Identification - Cockroaches of Florida 1 A Dichotomous Key for the Identification of the Cockroach fauna (Insecta: Blattaria) of Florida Insect Classification Exercise Department of Entomology and Nematology University of Florida, Gainesville 32611 Abstract: Students used available literature and specimens to produce a dichotomous key to species of cockroaches recorded from Florida. This exercise introduced students to techniques used in studying a group of insects, in this case Blattaria, to produce a regional species key. Producing a guide to a group of insects as a class exercise has proven useful both as a teaching tool and as a method to generate information for the public. Key Words: Blattaria, Florida, Blatta, Eurycotis, Periplaneta, Arenivaga, Compsodes, Holocompsa, Myrmecoblatta, Blatella, Cariblatta, Chorisoneura, Euthlastoblatta, Ischnoptera,Latiblatta, Neoblatella, Parcoblatta, Plectoptera, Supella, Symploce,Blaberus, Epilampra, Hemiblabera, Nauphoeta, Panchlora, Phoetalia, Pycnoscelis, Rhyparobia, distributions, systematics, education, teaching, techniques. Identification of cockroaches is limited here to adults. A major source of confusion is the recogni- tion of adults from nymphs (Figs. 1, 2). There are subjective differences, as well as morphological differences. Immature cockroaches are known as nymphs. Nymphs closely resemble adults except nymphs are generally smaller and lack wings and genital openings or copulatory appendages at the tip of their abdomen. Many species, however, have wingless adult females. Nymphs of these may be recognized by their shorter, relatively broad cerci and lack of external genitalia. Male cockroaches possess styli in addition to paired cerci. Styli arise from the subgenital plate and are generally con- spicuous, but may also be reduced in some species. Styli are absent in adult females and nymphs. -

Unusual Macrocyclic Lactone Sex Pheromone of Parcoblatta Lata, a Primary Food Source of the Endangered Red-Cockaded Woodpecker

Unusual macrocyclic lactone sex pheromone of Parcoblatta lata, a primary food source of the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker Dorit Eliyahua,b,1,2, Satoshi Nojimaa,b,1,3, Richard G. Santangeloa,b, Shannon Carpenterc,4, Francis X. Websterc, David J. Kiemlec, Cesar Gemenoa,b,5, Walter S. Leald, and Coby Schala,b,6 aDepartment of Entomology and bW. M. Keck Center for Behavioral Biology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695; cDepartment of Chemistry, College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, Syracuse, NY 13210; and dDepartment of Entomology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616 Edited by May R. Berenbaum, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL, and approved November 28, 2011 (received for review July 20, 2011) Wood cockroaches in the genus Parcoblatta, comprising 12 species Identification of the sex pheromone of P. lata has important endemic to North America, are highly abundant in southeastern implications in biological conservation and forest management pine forests and represent an important prey of the endangered practices. This species and seven related species in the genus red-cockaded woodpecker, Picoides borealis. The broad wood cock- Parcoblatta inhabit standing pines, woody debris, logs, and snags roach, Parcoblatta lata, is among the largest and most abundant of in pine forests of the southeastern United States, and they rep- the wood cockroaches, constituting >50% of the biomass of the resent the most abundant arthropod biomass in this habitat (4). woodpecker’s diet. Because reproduction in red-cockaded wood- Most importantly, P. lata constitutes a significant portion peckers is affected dramatically by seasonal and spatial changes (>50%) of the diet of the endangered red-cockaded wood- P. -

Phylogeny and Life History Evolution of Blaberoidea (Blattodea)

78 (1): 29 – 67 2020 © Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, 2020. Phylogeny and life history evolution of Blaberoidea (Blattodea) Marie Djernæs *, 1, 2, Zuzana K otyková Varadínov á 3, 4, Michael K otyk 3, Ute Eulitz 5, Kla us-Dieter Klass 5 1 Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom — 2 Natural History Museum Aarhus, Wilhelm Meyers Allé 10, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark; Marie Djernæs * [[email protected]] — 3 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Sci- ence, Charles University, Prague, 12844, Czech Republic; Zuzana Kotyková Varadínová [[email protected]]; Michael Kotyk [[email protected]] — 4 Department of Zoology, National Museum, Prague, 11579, Czech Republic — 5 Senckenberg Natural History Collections Dresden, Königsbrücker Landstrasse 159, 01109 Dresden, Germany; Klaus-Dieter Klass [[email protected]] — * Corresponding author Accepted on February 19, 2020. Published online at www.senckenberg.de/arthropod-systematics on May 26, 2020. Editor in charge: Gavin Svenson Abstract. Blaberoidea, comprised of Ectobiidae and Blaberidae, is the most speciose cockroach clade and exhibits immense variation in life history strategies. We analysed the phylogeny of Blaberoidea using four mitochondrial and three nuclear genes from 99 blaberoid taxa. Blaberoidea (excl. Anaplectidae) and Blaberidae were recovered as monophyletic, but Ectobiidae was not; Attaphilinae is deeply subordinate in Blattellinae and herein abandoned. Our results, together with those from other recent phylogenetic studies, show that the structuring of Blaberoidea in Blaberidae, Pseudophyllodromiidae stat. rev., Ectobiidae stat. rev., Blattellidae stat. rev., and Nyctiboridae stat. rev. (with “ectobiid” subfamilies raised to family rank) represents a sound basis for further development of Blaberoidea systematics. -

Brown-Banded Cockroach

Pest Profile Photo credit: Daniel R. Suiter, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org Common Name: Brown-banded Cockroach Scientific Name: Supella longipalpa Order and Family: Blattodae, Ectobiidae (formerly Blattellidae) Size and Appearance: Length (mm) Appearance Egg Yellowish to reddish-brown in color containing roughly 18 Egg case (ootheca)- eggs 5mm Larva/Nymph Similar to adults but lacking wings Adult Males- 13-14.5mm Dark brown color with two prominent light brown bands Females- 10-12mm on anterior part of abdomen. Males have wings that extend full length of abdomen and females have shortened wings inhibiting them from flight. Pupa (if applicable) Type of feeder (Chewing, sucking, etc.): Chewing mouthparts Host plant/s: Brown-banded cockroaches feed on a variety of substances such as glue, paper products, clothes, animal residues and tend to be opportunistic feeders. Description of Damage (larvae and adults): Brown-banded cockroaches are domestic pests that tend to be dispersed throughout homes that are infested. They are opportunistic feeders and will eat most anything including paper goods such as wallpaper. As a public health concern, contamination from feces, body parts and shed skins are a common cause for allergies and increased incidences of asthma. These roaches can mechanically transmit pathogens from contact from their bodies. References: Le Guyader, A., Rivault, C., & Chaperon, J. (1989). Microbial organisms carried by brown-banded cockroaches in relation to their spatial distribution in a hospital. Epidemiology & Infection, 102(3), 485- 492. Jacobs, S. (2013). Brown-Banded Cockroaches. Insect Advice from Extension. Pennsylvania State University. https://ento.psu.edu/extension/factsheets/brown-banded-cockroaches Jiang, S., & Lucky, A. -

Arthropods of Public Health Significance in California Exam Section C Terrestrial Invertebrate Vector Control

Arthropods of Public Health Significance in California Exam Section C Terrestrial Invertebrate Vector Control > EXIT Main Menu How to Use Primitive Honey Bees This Guide Flies Scorpions Epidemiology of Brachyceral Vector-Borne Flies Diseases Spiders Fundamentals Higher of Entomology Flies Mites Cockroaches Fleas Ticks Biting and Yellowjackets, Sucking Lice Hornets, and Wasps Field True Common Pest Safety Bugs Ants CDPH, Vector-Borne Disease Section EXIT How to Use this Guide . This study guide is meant to supplement your reading of the manual, Arthropods of Public Health Significance in California, and is not intended as a substitute. You can navigate through the guide at your own pace and in any order. You can always return to the Main Menu if you get lost or want to skip to another section. Click the “underlined text” within the presentation to move to additional information within that section. Use the Section icon Menu to return to the beginning of that section. Click the buttons at the bottom of each page to navigate through the training presentation. Use the < to navigate to the PREVIOUSLY viewed slide. Use the > to navigate to the NEXT slide within that section if applicable. You can also use the “page up” and “page down” keys to move between slides. At anytime you may “click” any of the additional buttons to return to the main menu or exit the presentation. CDPH, Vector-Borne Disease Section Main Menu Exit Epidemiology of Vector- Borne Diseases Introduction Epidemiologic Terms Methods of Transmission Vectorial Capacity Landscape Epidemiology Assessment and Prediction of Disease Risk < > CDPH, Vector-Borne Disease Section Main Menu Exit Introduction Epidemiology is the study of human disease patterns – Some examples include malaria, plague, murine typhus, St. -

The First Report of Drug Resistant Bacteria Isolated from the Brown-Banded Cockroach, Supella Longipalpa, in Ahvaz, South-Western Iran

J Arthropod-Borne Dis, June 2014, 8(1): 53–59 B Vazirianzadeh et al.: The First Report of … Original Article The First Report of Drug Resistant Bacteria Isolated from the Brown-Banded Cockroach, Supella longipalpa, in Ahvaz, South-western Iran Babak Vazirianzadeh 1, *Rouhullah Dehghani 2, Manijeh Mehdinejad 3, Mona Sharififard 4, Nersi Nasirabadi 3 1Department of Medical Entomology, College of Health and Infectious and Tropical disease Research Centre, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran 2Department of Environmental Health, College of Health and Social Determinants of Health (SDH),Research Center, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran 3Departments of Medical Microbiology, College of Medicine, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran 4Departments of Medical Entomology, College of Health, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sci- ences, Ahvaz, Iran (Received 7 July 2012; accepted 30 June 2013) Abstract Background: The brown-banded cockroach, Supella longipalpa is known as a carrier of pathogenic bacteria in ur- ban environments, but its role is not well documented regarding the carriage of antibiotic-resistant pathogenic bacte- ria in Iran. The aim of this study was to determine the resistance bacteria isolated from the brown-banded cockroach in Ahvaz, south west of Iran. Methods: Totally 39 cockroaches were collected from kitchen area of houses and identified. All specimens were cultured to isolate the bacterial agents on blood agar and MacConky agar media. The microorganisms were identified using necessary differential and biochemical tests. Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed for isolated or- ganisms by Kirby-Bauer’s disk diffusion according to NCLI guideline, using 18 antibiotics. -

Mites and Endosymbionts – Towards Improved Biological Control

Mites and endosymbionts – towards improved biological control Thèse de doctorat présentée par Renate Zindel Université de Neuchâtel, Suisse, 16.12.2012 Cover photo: Hypoaspis miles (Stratiolaelaps scimitus) • FACULTE DES SCIENCES • Secrétariat-Décanat de la faculté U11 Rue Emile-Argand 11 CH-2000 NeuchAtel UNIVERSIT~ DE NEUCHÂTEL IMPRIMATUR POUR LA THESE Mites and endosymbionts- towards improved biological control Renate ZINDEL UNIVERSITE DE NEUCHATEL FACULTE DES SCIENCES La Faculté des sciences de l'Université de Neuchâtel autorise l'impression de la présente thèse sur le rapport des membres du jury: Prof. Ted Turlings, Université de Neuchâtel, directeur de thèse Dr Alexandre Aebi (co-directeur de thèse), Université de Neuchâtel Prof. Pilar Junier (Université de Neuchâtel) Prof. Christoph Vorburger (ETH Zürich, EAWAG, Dübendorf) Le doyen Prof. Peter Kropf Neuchâtel, le 18 décembre 2012 Téléphone : +41 32 718 21 00 E-mail : [email protected] www.unine.ch/sciences Index Foreword ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Zusammenfassung ........................................................................................................................ 5 Résumé ....................................................................................................................................... -

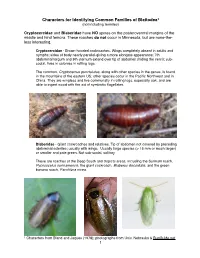

Characters for Identifying Common Families of Blattodea1 (Not Including Termites)

Characters for Identifying Common Families of Blattodea1 (not including termites) Cryptocercidae and Blaberidae have NO spines on the posteroventral margins of the middle and hind femora. These roaches do not occur in Minnesota, but are none-the- less interesting. Cryptocercidae - Brown-hooded cockroaches. Wings completely absent in adults and nymphs; sides of body nearly parallel-giving a more elongate appearance; 7th abdominal tergum and 6th sternum extend over tip of abdomen (hiding the cerci); sub- social, lives in colonies in rotting logs. The common, Cryptocercus punctulatus, along with other species in the genus, is found in the mountains of the eastern US; other species occur in the Pacific Northwest and in China. They are wingless and live communally in rotting logs, especially oak, and are able to ingest wood with the aid of symbiotic flagellates. Blaberidae - Giant cockroaches and relatives. Tip of abdomen not covered by preceding abdominal sclerites; usually with wings. Usually large species (> 15 mm or much larger) or smaller and pale green. Not sub-social, solitary These are roaches of the Deep South and tropical areas, including the Surinam roach, Pycnoscelus surinamensis, the giant cockroach, Blaberus discoidalis, and the green banana roach, Panchlora nivea. 1 Characters from Bland and Jaques (1978); photographs from Univ. Nebraska & BugGuide.net !1 Ectobiidae (=Blattellidae)2 and Blattidae have numerous spines on the posteroventral margins of the middle and hind femora. These roaches do occur in Minnesota. Ectobiidae (=Blattellidae) (in part) - Parcoblatta. Front femur with row of stout spines on posteroventral margin and with shorter and more slender spines basally (in other words, the spines are in 2 distinct size groups). -

Cockroach IPM in Schools Janet Hurley, ACE Extension Program Specialist III What Are Cockroaches?

Cockroach IPM in schools Janet Hurley, ACE Extension Program Specialist III What are cockroaches? • Insects in the Order Blattodea • gradual metamorphosis • flattened bodies • long antennae • shield-like pronotum covers head • spiny legs • Over 3500 species worldwide • 5 to 8 commensal pest species Medical Importance of Cockroaches • Vectors of disease pathogens • Food poisoning • Wound infection • Respiratory infection • Dysentery • Allergens • a leading asthma trigger among inner city youth Health issues • Carriers of disease pathogens • Mycobacteria, Staphylococcus, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Citrobacter, Providencia, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Flavobacter • Key focus of health inspectors looking for potential contaminants and filth in food handling areas Cockroaches • No school is immune • Shipments are • Visitors Everywhere • Students Cockroach allergies • 37% of inner-city children allergic to cockroaches (National Cooperative Inner-City Asthma Study) • Increased incidence of asthma, missed school, hospitalization • perennial allergic rhinitis Not all cockroaches are created equal Four major species of cockroaches • German cockroach • American cockroach • Oriental cockroach • Smoky brown cockroach • Others • Turkestan cockroach • brown-banded cockroach • woods cockroach German cockroach, Blatella germanica German cockroach life cycle German cockroach • ½ to 5/8” long (13-16 mm) • High reproductive rate • 30-40 eggs/ootheca • 2 months from egg to adult • Do not fly • Found indoors in warm, moist areas in kitchens and bathrooms German