The Time of Fulfillment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Problem of Mysteriousness of Baba Yaga Character in Religious Mythology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 12 (2013 6) 1857-1866 ~ ~ ~ УДК 7.046 The Problem of Mysteriousness of Baba Yaga Character in Religious Mythology Evgenia V. Ivanova* Ural Federal University named after B.N. Yeltsin 51 Lenina, Ekaterinburg, 620083 Russia Received 28.07.2013, received in revised form 30.09.2013, accepted 05.11.2013 This article reveals the ambiguity of interpretation of Baba Yaga character by the representatives of different schools of mythology. Each of the researchers has his own version of the semantic peculiarities of this culture hero. Who is she? A pagan goddess, a priestess of pagan goddesses, a witch, a snake or a nature-deity? The aim of this research is to reveal the ambiguity of the archetypical features of this character and prove that the character of Baba Yaga as a culture hero of the archaic religious mythology has an influence on the contemporary religious mythology of mass media. Keywords: religious mythology, myth, culture hero, paganism, symbol, fairytale, religion, ritual, pagan priestess. Introduction. “Religious mythology” is examined by the author of the article (Ivanova, a new term, which is relevant to contemporary 2012, p.56). The subject of the research presented religious and cultural studies, philosophy in this article is topography or conceptual space of religion and other sciences focusing on of notional understanding of the fairytale pagan correlation between myth and religion. This culture hero – the character of Baba Yaga. -

A Short History of Russian Literature

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Short history of Russian iiterature 3 1924 026 645 790 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026645790 1 A SHORT HISTORY OF RUSSIAN LITERATURE Translated from the Russian OF SHAKHNOVSKI With a Supplementary Chapter bringing the work down to date (written specially for this book) BY SERGE TOMKEYEFF London KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & Co., Ltd. New York : E. P. BUTTON & Co. 193 f\.S^1\3 4- V. ^.. \'-"f .. CONTENTS PAGE Introductory . i Chap I. Oral and written literature . 3 II. The beginnings of written literature . 9 III. The monuments of the twelfth century r8. IV. The monuments of the thirteenth century 22 V. The monuments of the fourteenth century 24 VI. The modern period . 30 VII. The epoch of reconstruction . 36 VIII. Sumar6kov and the literary writers under Catherine II . 46 IX Von Visin 52 X. The first Russian periodicals . 62 XI. N. Y. Karamzln . 66 XII. Zhuk6vski 74 XIII. Kryl6v and the journalism of the Romantic epoch . 81 XIV. A. S. Pushkin and his followers . 86 XV. Griboiedov, Lermontov . 99 XVI. Gogol 106 XVII. Modem Literature : The Schellingists, Slavophils and Westemizers . 117 XVIII. Later poets and the great novelists . 123 XIX. Grigor6vich and other novelists . 131 XX. Russian Literature from Leo Toistoy to the present date . 138 (Writter. by Serge Tomkeyeff./ INTRODUCTORY. The history of literature presents a progressive develop- ment of the art of writing in every country, and is corre- lated with the culture of the people. -

Russian Byliny As Discursive Space

Putting Words in Their Mouths: Russian Byliny as 83 Discursive Space Putting Words in Their Mouths: Russian Byliny as Discursive Space Kate Christine Moore Koppy Marymount University and the University of the District of Columbia Community College Arlington, Virginia, United States of America Abstract This article follows the Melnitsa Animation Studio into the imagined medieval space of their bogatyr films. With particular focus on Melnitsa’s use of the Il’ia Muromets corpus in Илья Муромец и Соловей Разбойник [Il’ia and the Robber], we consider the complex set of conflicts among characters and ideas that reflect concepts of identity and social issues in contemporary Russia. In moments of cultural unrest, adaptations of canonical stories serve as a discursive space for the community to redefine itself. In the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries, the byliny [western Slavic heroic epics] have functioned as tools of cultural cohesion at critical moments of national self-redefinition. Most recently, the Студия анимационного кино Мельница [Melnitsa Animation Studio] (1) has adapted the byliny into animated films for children, in which stories of medieval princes, heroes, and villains become a discursive space for the exploration of social issues in the post-Soviet Russian Federation. Melnitsa’s 2007 film Il’ia and the Robber is the most recent example in a steady stream of adaptation and retelling of byliny from the time they were first printed to the present. Along that timeline, there are three moments in which adaptations flourish, and each of these coincides with a crucial moment of redefinition of Russian culture. The nineteenth century recording of these heroic epics, which adapts them from dynamic oral epics to written texts (2), was part of the wave of romantic nationalism that drove scholars across Europe to gather folkloric material as the feudal city-states of the medieval period coalesced into more stable nations. -

“Zhili-Byli…”: Russian Folklore in the Intermediate Language Classroom

“Zhili-byli…”: Russian Folklore in the Intermediate Language Classroom BLC Project, Fall 2019 Kit Pribble (GSR, Slavic Dept.) Textual features of the fairytale ◦ Formulaic, often cyclical narrative structure ◦ Combination of vivid imagery + concrete plot ◦ Repetition and the rule of 3 ◦ Orality (alliteration, rhyme, & mnemonic devices) Project Goals 1) To gradually build students’ comfort level with reading narrative texts in Russian 2) To introduce students to a foundational aspect of Russian culture, while also engaging students in a critical consideration of how national cultures are conceived or constructed Focus: Traditional Magic Tales and their 20th Century Adaptations 1) Recorded textual variants • Alexander Afanasyev’s collection of Russian fairytales, 1860s 2) 20th century revisions and adaptations • Ballets (Modernist and Soviet) • Modernist paintings and illustrations • Soviet rock music • Animated films (Soviet and Post-Soviet) • Advertisements • Political emblems and political cartoons Project Goals 1) To gradually build students’ comfort level with reading narrative texts in Russian 2) To introduce students to a foundational aspect of Russian culture, while also engaging students in a critical consideration of how national cultures are conceived or constructed Cluster 1: The 3 Bogatyrs Learning goals: 1) Introduce students to the genre of the bylina (East Slavic heroic epic), as well as later re-castings of the bogatyrs (Slavic epic heroes) in Modernist and Post-Soviet art 2) Increase students’ sensitivity to register and -

RUSSIAN MYTHOLOGY Ayse Dietrich, Ph.D

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE RUSSIAN MYTHOLOGY Ayse Dietrich, Ph.D. Introduction Mythology takes as its subject the significance of the objects that exist in the world, natural events, and the private matters and objects of social life from an emotional point of view. Mythology is the identification of humanity with nature, making the powers of nature one’s own in the imagination. In the face of natural events, the first humans were powerless, both before the events within themselves and those that came from outside. Therefore, it is directed at describing events and objects that were considered taboo, or embodying and personalizing events or objects that the mind could not grasp. Identifying itself with all living and non-living thing from the very beginning, the human mind tried to express them through various objects and symbols. The rustle of leaves, thunder, bird calls, and lightning striking – all these natural events were perceived by humans as a sign of good or evil, life or death. Mythological images are indirect expressions of humans’ internal worlds and emotions. Emotions override reason. Mythological images do not consist only of imaginary depictions. They also have the quality of making living in harmony with human desires and emotions, and acting together easier. In this context, The subject of Russian mythology consists of the belief of the Russian people, who planted fields, worked the land, and spent their lives together with animals such as eagles and wolves, that supernatural powers directed the fates of men, and the symbols and gods that before and after the coming of Christianity were passed down from generation to generation. -

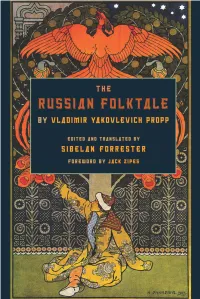

Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp

Series in Fairy-Tale Studies General Editor Donald Haase, Wayne State University Advisory Editors Cristina Bacchilega, University of Hawai`i, Mānoa Stephen Benson, University of East Anglia Nancy L. Canepa, Dartmouth College Isabel Cardigos, University of Algarve Anne E. Duggan, Wayne State University Janet Langlois, Wayne State University Ulrich Marzolph, University of Gött ingen Carolina Fernández Rodríguez, University of Oviedo John Stephens, Macquarie University Maria Tatar, Harvard University Holly Tucker, Vanderbilt University Jack Zipes, University of Minnesota A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu W5884.indb ii 8/7/12 10:18 AM THE RUSSIAN FOLKTALE BY VLADIMIR YAKOVLEVICH PROPP EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY SIBELAN FORRESTER FOREWORD BY JACK ZIPES Wayne State University Press Detroit W5884.indb iii 8/7/12 10:18 AM © 2012 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. English translation published by arrangement with the publishing house Labyrinth-MP. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data 880-01 Propp, V. IA. (Vladimir IAkovlevich), 1895–1970, author. [880-02 Russkaia skazka. English. 2012] Th e Russian folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp / edited and translated by Sibelan Forrester ; foreword by Jack Zipes. pages ; cm. — (Series in fairy-tale studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8143-3466-9 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 978-0-8143-3721-9 (ebook) 1. Tales—Russia (Federation)—History and criticism. 2. Fairy tales—Classifi cation. 3. Folklore—Russia (Federation) I. -

Role of the Folk Songs in the Russian Opera of the 18Th Century Adriana Pilip-Siroki

Role of the Folk Songs in the Russian Opera of the 18th Century Adriana Pilip-Siroki Listaháskóli Íslands Tónlistardeild Söngur Role of the Folk Songs in the Russian Opera of the 18th Century Adriana Pilip-Siroki Supervisor: Gunnsteinn Ólafsson Spring 2011 Abstract of the work The last decades of the 18th century were a momentous period in Russian history; they marked an ever-increasing awareness of the horrors of serfdom and the fate of peasantry. Because of the exposure of brutal treatment of the serfs, the public was agitating for big reforms. In the 18th century these historical circumstances and the political environment affected the artists. The folk song became widely reflected in Russian professional music of the century, especially in its most important genre, the opera. The Russian opera showed strong links with Russian folklore from its very first appearance. This factor differentiates it from all other genres of the 18th century, which were very much under the influence of classicism (painting, literature, architecture). About one hundred operas were created in the last decades of the 18th century, but only thirty remained; of which fifteen make use of Russian and Ukrainian folk music. Gathering of folk songs and the first attempts to affix them to paper were made in this period. In course of only twenty years, from its beginning until the turn of the century, Russian opera underwent a great change: it became into a fully-fledged genre. Russian opera is an important part of the world’s theatre music treasures, and the music of the 18th century was the foundation of the mighty achievements of the second half of the 19th century, embodied in the works of Mussorgsky, Tchaikovsky, Borodin, and Rimsky-Korsakov. -

Natalia Goncharova Large Print Guide

NATALIA GONCHAROVA 6 June – 8 September 2019 LARGE PRINT GUIDE CONTENTS Room 1 ................................................................................3 Room 2 .............................................................................. 14 Room 3 .............................................................................. 21 Room 4 .............................................................................. 41 Room 5 ..............................................................................52 Room 6 ..............................................................................59 Room 7 ..............................................................................64 Room 8 ..............................................................................79 Room 9 ..............................................................................91 Room 10 ............................................................................98 Find out more .................................................................. 122 Credits ............................................................................. 125 2 ROOM 1 THE COUNTRYSIDE I loved the countryside all my life but I live in the city… —Natalia Goncharova Natalia Goncharova produced an astonishing variety of work, crossing the boundaries between art and design. Living first in Russia, then in France, she was a painter, print- maker, illustrator and fashion designer, as well as a set and costume designer for the Ballets Russes. Goncharova was born in Russia in 1881. She grew up -

Russian Nationalism

Russian Nationalism This book, by one of the foremost authorities on the subject, explores the complex nature of Russian nationalism. It examines nationalism as a multi layered and multifaceted repertoire displayed by a myriad of actors. It considers nationalism as various concepts and ideas emphasizing Russia’s distinctive national character, based on the country’s geography, history, Orthodoxy, and Soviet technological advances. It analyzes the ideologies of Russia’s ultra nationalist and far-right groups, explores the use of nationalism in the conflict with Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea, and discusses how Putin’s political opponents, including Alexei Navalny, make use of nationalism. Overall the book provides a rich analysis of a key force which is profoundly affecting political and societal developments both inside Russia and beyond. Marlene Laruelle is a Research Professor of International Affairs at the George Washington University, Washington, DC. BASEES/Routledge Series on Russian and East European Studies Series editors: Judith Pallot (President of BASEES and Chair) University of Oxford Richard Connolly University of Birmingham Birgit Beumers University of Aberystwyth Andrew Wilson School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London Matt Rendle University of Exeter This series is published on behalf of BASEES (the British Association for Sla vonic and East European Studies). The series comprises original, high quality, research level work by both new and established scholars on all aspects of Russian, -

How American Authors Reinvent Russian Fairy Tales Sarah Krasner Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 Adapting Skazki: How American Authors Reinvent Russian Fairy Tales Sarah Krasner Scripps College Recommended Citation Krasner, Sarah, "Adapting Skazki: How American Authors Reinvent Russian Fairy Tales" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 1055. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1055 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADAPTING SKAZKI: HOW AMERICAN AUTHORS REINVENT RUSSIAN FAIRY TALES by SARAH KRASNER SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR RUDOVA PROFESSOR DRAKE APRIL 21, 2017 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………iii A Note on Transliteration………………………………………………………………………...iv Glossary of Terms………………………………………………………………………………....v Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………….1 Translation and Adaptation Intertextuality Baba Yaga Chapter One: Enchantment………………………………………………………………………13 The Hypotext Fairy Tale: Sleeping Beauty The Hero and the Princess History, Time, and Fiction Baba Yaga Enchantment’s Political Discourse Enchantment’s Meta Aspects Chapter Two: Dreaming Anastasia………………………………………………………………29 The Hypotext Fairy Tale: Vasilisa the Brave The Heroine and the Hero History, Time, and Fiction Baba Yaga Rusalki Koschei the Deathless Three Family and Grief Dreaming Anastasia’s Meta Aspects Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….54 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………...57 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work would not exist without the support and guidance of Professor Larissa Rudova, who encouraged me to decide on a topic early, allowed me to do an independent study with her to gain much of the base knowledge needed for the project, and oversaw the writing process. -

Gorbachev and Yeltsin's Masculinities by Lindsay

! “He Carried Himself Like a Man”: Gorbachev and Yeltsin’s Masculinities By Lindsay Sovern Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In the Department of History at Brown University Thesis Advisor: Patricia Herlihy, Professor Emerita April 4, 2014 Introduction There is little doubt that the two men who most influenced the collapse of the Soviet Union were Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and Russian President Boris Yeltsin. Historians have considered their individual personalities and relationship with each other as instrumental in dismantling one of the greatest superpowers of modernity. Historian George W. Breslauer calls both Gorbachev and Yeltsin “Event-Making Men,” meaning that they were both responsible for events that brought about the disintegration of the Soviet Union.1 However, Breslauer does not interrogate the gendered implications of that term, or even acknowledge that the term defines agency in masculine terms. In fact, no historians have explicitly considered the gendered aspects of Gorbachev and Yeltsin’s public images. This thesis explores the transfer of political power from Gorbachev to Yeltsin in 1991, as one that transpired between two men with at times similar, but distinct masculine images. Why consider the gendered aspects of Gorbachev and Yeltsin’s public images at all? In her explanation of gender history and why it matters, historian Naoko Shibusawa argues that gender is worth studying because of its role in shaping hierarchy—that is to say, “Presumptions about male superiority, however, have been so ingrained that it has appeared ‘natural’ that men should rule, while women should be ruled.”2 Gender histories challenge the naturalness of male domination, and this project is no different. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov the Antiquarian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov the Antiquarian: The Narrativity of Diegetic Song in the Opera Sadko A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Jeffrey T. Riggs 2019 © Copyright by Jeffrey T. Riggs 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov the Antiquarian: The Narrativity of Diegetic Song in the Opera Sadko by Jeffrey T. Riggs Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Chair Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov subtitled Sadko “an Opera-Bylina,” a gesture which both reveals his compositional approach, and gives the piece a sui generis designation as an operatic and folk-epic hybrid. The composer drew from an extraordinary range of textual and musical material to fashion Sadko, a work that is thoroughly imbued with references to Russian folk culture. His primary source texts were the Russian byliny: folk-epic poetry that had circulated orally for some seven centuries before being collected and transcribed in the nineteenth century. While Rimsky-Korsakov’s preoccupation with folklore represents a thematic continuation of his prior operas, his approach to his source material takes a decidedly antiquarian and philological turn in Sadko. ii Rimsky-Korsakov’s transmutation of the byliny into operatic form involved his development of a set of narrative strategies that approximate the storytelling conventions of the source texts. Rimsky-Korsakov includes multiple narrators in the opera who present Sadko’s tale through different narrative frames, chronotopes, and musical idioms. The arias of each narrator constitute moments of heightened narrativity, in which the events of the plot are condensed, refracted, retold, and foretold through the prism of diegetic song.