Merchant Bank Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Washington Associates Washington, D.C. December,,: 198

5 1- BANK JAMAICA/U.S. FULL SERVICE MERCHANT DEVELOPMENT CONCEPT-PAPER' Prepared by First Washington Associates Washington, D.C. December,,: 198 .2.1 TABLE!OF CONTENTS Page 1. Concept. * 1* II. Economic Climate and Private Investment . .4 III. Existing Financial Infrastructure ..... 7 IV. Activities of the New Bank . ... 13 V. Formation, Ownership, and Capitalization ,19 VI. Direction and Management,. .. " .22 VII. Implementation . ' .• ****25 0-H- I. CONCEPT 1. This discussion paper has been prepared at the,, request of the Bureau for Private Enterprise (PRE) and the Jamaican Mission of the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID) and is intended to describe the role which a new Jamaica/U.S. Full-Service Merchant Development Bank can play in helping achieve economic development and growth through expansion and stimulation of the private sector in Jamaica. 2. Under the Government of Prime Minister Seaga, Jamaica has embarked upon a serious, across-the-board program of measures to encourage expansion of private sector productivity and output and lead to substantial new investments in agri culture, manufacturing, and related service industries. The private sector is looked upon as the major driving force for economic rehabilitation, and investments from the United States and local entrepreneurs are being counted upon to bring new vitality and diversification to the Jamaican economy, reverse the outward flow of private capital, transfer new technologies, and help solve the country's balance of payments and unemployment problems. 3. Seriously limiting the achievement of these goals is the lack of an adequate institutional infrastructure to provide equity funding and aggressive medium- and long-term credit facilities to stimulate capital investment. -

BR-69915-210X297mm-Update the UBS Securities China Brochure

UBS Securities First foreign-invested fully-licensed securities firm in China, 51% owned by UBS AG He Di Eugene Qian UBS Securities Co., Limited (UBS Securities) was incorporated on 11 December 2006 following the restructuring of Beijing Securities Co., Limited. In December 2018, UBS AG increased its shareholding in UBS Securities to 51%; the first time that a foreign financial institution had raised its stake to take majority control of a securities joint venture in China. With the support of the UBS Group and the dedication of our employees, UBS Securities remains at the forefront of the industry as the first foreign-invested fully-licensed securities firm in China. Client-centric and committed to the pursuit of excellence and sustainable performance, UBS Securities relies on international experience complemented by local expertise to maintain its market- leading position. Our success would not have been possible without our employees. We would also like to thank our clients, shareholders, business partners, as well as government and regulatory bodies for their support which has been a driving force for the business. Our market position today is a strong foundation for the decades to come. We are determined to build on our core strengths to capture the opportunities arising from ongoing wealth creation, market reforms and globalization in China. We will continue to offer world-class products, services and advice to our clients, and work with all stakeholders towards the further development of China’s financial markets. Very best wishes. He Di Eugene Qian Chairman President UBS Securities UBS Securities 2 Milestones Moving forward December 2018 UBS AG increased its shareholding in UBS Securities to 51%, first international bank to increase stake to take majority control in a China securities joint venture. -

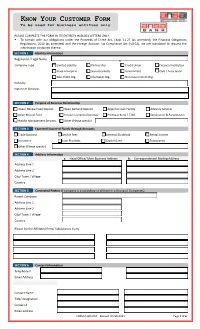

Know Your Customer Form

KNOW Y OUR C USTOMER F ORM To be used for business entities only PLEASE COMPLETE THE FORM IN ITS ENTIRETY IN BLOCK LETTERS ONLY . To comply with our obligations under the Proceeds of Crime Act, Chap. 11.27 (as amended), the Financial Obligations Regulations, 2010 (as amended) and the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), we are mandated to request the information contained therein. SECTION 1 Identity Information Registered / Legal Name Company Type Limited Liability Partnership Credit Union Financial Institution State Enterprise Statutory Body Government Club / Association Non-Profit Org. Charitable Org. Non-Government Org. Industry Nature of Business SECTION 2 Purpose of Business Relationship Open/ Renew Fixed Deposit Open Demand Deposit Apply for Loan Facility Advisory Services Open Mutual Fund Foreign Currency Exchange Purchase Bond / T-Bill Syndication & Participation Wealth Management Services Other (Please specify) SECTION 3 Expected Source of Funds through Accounts Trade Business Service Fees Interest/ Dividends Rental Income Donations Loan Proceeds Capital Gains Subsidiaries Other (Please specify) SECTION 4 Address Information a. Head Office/ Main Business Address b. Correspondence/ Mailing Address Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City/ Town / Village Country SECTION 5 Connected Parties (if company is a subsidiary or affiliate in a Group of Companies) Parent Company Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City/ Town / Village Country Please list the Affiliated firms/ Subsidiaries if any SECTION 6 Contact -

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

Federal Register / Vol. 69, No. 163 / Tuesday, August 24, 2004 / Proposed Rules 51979 (3) Covered financial institution has to document its compliance with the include the agency name and the the same meaning as provided in notice requirement set forth in Regulatory Information Number (RIN) § 103.175(f)(2) and also includes: paragraph (b)(2)(i)(A) of this section. for this proposed rulemaking. All (i) A futures commission merchant or (ii) Nothing in this section shall comments received will be posted an introducing broker registered, or require a covered financial institution to without change to http:// required to register, with the report any information not otherwise www.fincen.gov, including any personal Commodity Futures Trading required to be reported by law or information provided. Comments may Commission under the Commodity regulation. be inspected at FinCEN between 10 a.m. Exchange Act (7 U.S.C. 1 et seq.); and Dated: August 18, 2004. and 4 p.m., in the FinCEN reading room (ii) An investment company (as in Washington, DC. Persons wishing to William J. Fox, defined in section 3 of the Investment inspect the comments submitted must Company Act of 1940 (15 U.S.C. 80a–5)) Director, Financial Crimes Enforcement request an appointment by telephoning Network. that is an open-end company (as defined (202) 354–6400 (not a toll-free number). [FR Doc. 04–19266 Filed 8–23–04; 8:45 am] in section 5 of the Investment Company FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Act (15 U.S.C. 80a–5)) and that is BILLING CODE 4810–02–P Office of Regulatory Programs, FinCEN, registered, or required to register, with at (202) 354–6400 or Office of Chief the Securities and Exchange DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Counsel, FinCEN, at (703) 905–3590 Commission under section 8 of the (not toll-free numbers). -

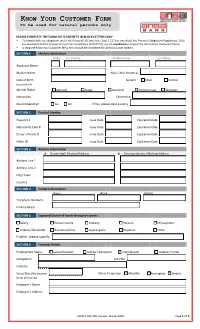

ABL KYC Form

KNOW YOUR C USTOMER F ORM To be used for natural persons only PLEASE COMPLETE THE FORM IN ITS ENTIRETY IN BLOCK LETTERS ONLY . To comply with our obligations under the Proceeds of Crime Act, Chap. 11.27 (as amended), the Financial Obligations Regulations, 2010 (as amended) and the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), we are mandated to request the information contained therein. A separate Know Your Customer (KYC) form should be completed for additional joint holders. SECTION 1. Identity Information Prefix First Name Middle Name Last Name Applicant Name Maiden Name Alias / Also known as Date of Birth Gender : Male Female (yyyy/mm/dd) Marital Status Married Single Divorced Common Law Widower Nationality Citizenship Dual Citizenship? YES NO If Yes, please state country SECTION 2. Proof of Identity Passport # Issue Date Expiration Date National ID Card # Issue Date Expiration Date Driver’s Permit # Issue Date Expiration Date Other ID Issue Date Expiration Date SECTION 3. Address Information a. Residential/ Physical Address b. Correspondence/ Mailing Address Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City/ Town Country SECTION 4. Contact Information Home Work Mobile Telephone Numbers Email address ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. SECTION 5. Expected Source of Funds through Accounts Salary Rental income Gratuity Pension NIS payment Interest/ Dividends Business profits Capital gains Royalties Other If other, please specify SECTION 6. Financial Details Employment Status salaried worker retiree / pensioner unemployed student / minor Occupation Job Title Industry Gross Monthly Income Salary frequency: Monthly Fortnightly Weekly (from all sources) Employer’s Name Employer’s Address FORM # GRC-001 (revised 18-Feb-2021) Page 1 of 4 SECTION 7. -

UMB Terms and Conditions

Terms and Conditions UNIVERSAL MERCHANT BANK ACCOUNT AGREEMENT AND DISCLOSURES The Account Agreement and Disclosures ("Agreement") is between you and UNIVERSAL MERCHANT Bank for the delivery of Account services as described below: 1.0 DEFINED TERMS. As used in the Terms and Conditions, the following terms shall have the following meaning: "Account" means a bank account/ credit card account and/ or any savings/ current/ overdraft/ cash credit account maintained by the user with the Bank and for which the facility is being offered "Bank" means UNIVERSAL MERCHANT Bank. "We," "Our," and "Us" means UNIVERSAL MERCHANT Bank. "You" and "Your" refers to each person who is named as the account holder. If there is more than one of you then it refers to both of you individually and jointly. "Customer" means account customers that have a UNIVERSAL MERCHANT Bank account and any of the e-channel services. "e-channel" Any of the following products- internet banking, SMS alert, telephone banking, ATM Debit card or any other electronic service provided solely by the bank or in partnership with any outfit. “Banking Day” means Monday to Friday and excluding Public Holidays “Banking hours” means the hours your branch is open for business “Authorised Signatory” means the account holder(s) in case of an individual account and a designated person or persons who are allowed to operate the accounts on behalf of a firm or organization "Alerts" means the customized messages sent to the User over his mobile phone as short messaging service ("SMS"). “Customer” means an individual, firm, partnership, enterprise or company or any legal person as defined in law. -

Homeready Mortgage

Chapter 3 Mortgage Loan Products and Product Matrix Contents Fixed-Rate Mortgage Loans ............................................................................................................................ 2 CONVENTIONAL CONFORMING LOANS ................................................................................................... 2 Construction to Permanent Loans ................................................................................................................. 3 Manufactured Housing .................................................................................................................................... 4 MANUFACTURED HOUSING-FANNIE MAE ................................................................................................ 4 MANUFACTURED HOUSING-FREDDIE MAC ............................................................................................. 5 Manufactured Housing Land & Home Ownership Requirements ............................................................. 6 Rural Development Guaranteed Loans .......................................................................................................... 6 Rural Development (RD) Program ............................................................................................................. 7 Fannie Mae Only .............................................................................................................................................. 9 DU Refi Plus-Fannie Mae Only ................................................................................................................... -

1914 and 1939

APPENDIX PROFILES OF THE BRITISH MERCHANT BANKS OPERATING BETWEEN 1914 AND 1939 An attempt has been made to identify as many merchant banks as possible operating in the period from 1914 to 1939, and to provide a brief profle of the origins and main developments of each frm, includ- ing failures and amalgamations. While information has been gathered from a variety of sources, the Bankers’ Return to the Inland Revenue published in the London Gazette between 1914 and 1939 has been an excellent source. Some of these frms are well-known, whereas many have been long-forgotten. It has been important to this work that a comprehensive picture of the merchant banking sector in the period 1914–1939 has been obtained. Therefore, signifcant efforts have been made to recover as much information as possible about lost frms. This listing shows that the merchant banking sector was far from being a homogeneous group. While there were many frms that failed during this period, there were also a number of new entrants. The nature of mer- chant banking also evolved as stockbroking frms and issuing houses became known as merchant banks. The period from 1914 to the late 1930s was one of signifcant change for the sector. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), 361 under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 B. O’Sullivan, From Crisis to Crisis, Palgrave Studies in the History of Finance, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96698-4 362 Firm Profle T. H. Allan & Co. 1874 to 1932 A 17 Gracechurch St., East India Agent. -

Contactless Payments Rising

THOUGHT SERIES Contactless Payments Rising An Investing Trend During Coronavirus Eric Greco, Portfolio Associate Dave Harrison Smith, CFA, Senior Vice President, Domestic Equities November 2020 The rise of digital payments It’s been seven decades since the advent of the modern day credit card in 1950 by the Diners Club. Since then, numerous countries have jettisoned cash and pivoted towards digital payments as the conventional payment method. Technological advancements, data security enhancements, and consumer preference for convenience have all under- pinned the secular trend of cash displacement and adoption of digital payments. In re- cent years, we have seen rapid global adoption of a superior form of digital payments: contactless payments (also known as “contactless”, “tap to pay”, “NFC payments”). Cur- rently, consumers interact with contactless payments through two primary forms – con- tactless-enabled credit and debit cards, and mobile wallets (such as Apple Pay, Google Pay, and Samsung Pay). While contactless payments are already popular in a number of countries globally, wide- spread adoption in the U.S. has lagged due to an underdeveloped payments infrastruc- ture. In spite of this, U.S. adoption of contactless payments appears to have reached an inflection point over the past year as merchant acceptance has become more widespread and leading financial institutions have begun issuing contactless credit and debit cards. With the COVID-19 pandemic serving as a tailwind, we’ve seen an acceleration in the secular trends of e-commerce -

Downloaded Directly Into the Internet Merchant’S Account

Order Code RL31476 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Electronic Payments and the U.S. Payments System June 27, 2002 Walter W. Eubanks and Pauline H. Smale Specialist in Economic Policy and Analyst in Financial Services Government and Finance Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Electronic Payments and the U.S. Payments System Summary The electronic and paper-based payments systems consist of the various means buyers and sellers use to transfer monetary value among themselves. Electronic payments have been playing a critical role on the wholesale side of the payments system for decades. Trillions of dollars per day have been transferred routinely and securely through the wholesale payments system among parties, such as banks, corporations, the Federal Reserve, the Department of the Treasury, and other government agencies. More recently, electronic payment technologies have migrated to the retail side of the system, to households and individuals. In retail, however, the most popular methods of payment remain the more costly paper-based cash and check payments. In 2000, by one estimate, paper-based transactions accounted for two-thirds of all consumer payments, despite the promise of cost savings and convenience. Nevertheless, the volume of electronic retail payments has increased more rapidly during the last decade. The increase in the volume of electronic payments using credit and debit cards grew from 14% of total consumer transactions in 1990 to 31% in 2000. Still, by 2010 consumers will still be making about 50% of their payments with paper, according to the Nilson Report, an industry publication. With the great majority of wholesale banking transactions (institution to institution) being conducted electronically, the cost savings and convenience of electronic payments are a normal part of wholesale banking. -

Merchant's B Erchant's Bank (In Organization): a Case Study : a Case

Journal of Business Cases and Applications Merchant’s b ank (in organization) : a case study James B. Bexley Sam Houston State University Bala Maniam Sam Houston State University Case Synopsis This case relates to a group of organizers attempting to charter a bank. It takes into account the capital issues, competitive issues, and demographic issues that impact the likelihood that the regulatory authorities will allow the charter of the bank. The case is set in a college town that is one of the fastest growing metropolitan statistical areas o f the nation. Even during the current economic downturn, the market has had only nominal downturns. Students are asked to determine if the market can support a new bank, to evaluate the proposed capital, and to determine the type charter to seek. Additi onally, they need to type of planning and market effort that should be used to ensure that the community will accept the new bank. They will need to evaluate the age groups to target and the strategies to employ. Keywords: Bank charter, Banking, Case, C apital, Management Merchant’s bank (in organization), Page 1 Journal of Business Cases and Applications INTRODUCTION Frank Thompson and the business associates he has identified believe that the banking industry as a financial intermediary can be run in a more efficient manner than traditional methods of bank management. This means developing core competencies and focus ing on these skills since the financial services industry is becoming increasingly competitive. Banks are branching into non-banking related activities and other financial firms are trying to get into banking. -

HEDGE FUND PRIME BROKERS HEDGE FUND PRIME BROKERS We Analyze the Activity of Hedge Fund Prime Brokers by Their Clients’ Fund Structure, Fund Size and More

HEDGE FUND PRIME BROKERS HEDGE FUND PRIME BROKERS We analyze the activity of hedge fund prime brokers by their clients’ fund structure, fund size and more. Fig. 1: Prime Brokers Servicing Single-Manager Hedge Funds (As at May 2018) Fig. 2: Prime Brokers Servicing CTAs (As at May 2018) No. of Known Proportion of Hedge No. of Known Firm Hedge Funds Funds Launched in Last Firm Serviced 12 Months Serviced CTAs Serviced Goldman Sachs 3,142 25% Société Générale Prime Services 117 Morgan Stanley Prime Morgan Stanley Prime Brokerage 81 3,033 32% Brokerage Goldman Sachs 70 J.P. Morgan 2,132 23% J.P. Morgan 66 Credit Suisse Prime Fund 1,345 15% Interactive Brokers 55 Services Deutsche Bank Global Prime Finance 48 UBS Prime Services 1,278 7% Credit Suisse Prime Fund Services 43 Bank of America Merrill Lynch 1,203 9% Bank of America Merrill Lynch 42 Deutsche Bank Global Prime 1,077 5% Finance SG Americas Securities 39 Citi Prime Finance 857 5% UBS Prime Services 39 Barclays 664 8% Source: Preqin Interactive Brokers 627 10% Source: Preqin Fig. 3: Prime Brokers Servicing Funds of Hedge Funds Fig. 4: Market Share of Leading Prime Brokers Servicing Hedge Funds No. of Known Funds of Firm Hedge Funds Serviced 40% Goldman Sachs 54 34% 35% 32% Morgan Stanley Prime Brokerage 43 30% J.P. Morgan 42 Interactive Brokers 23 25% 23% Citi Prime Finance 22 20% Deutsche Bank Global Prime Finance 20 15% 14% 14% Pershing Prime Services 18 10% Wells Fargo Prime Services 15 BNP Paribas Prime Brokerage 13 5% Proportion of Funds Serviced UBS Prime Services 12 0% Goldman Morgan J.P.