Logging in Sarawak JOANGOHUTAN Report April2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority

For Reference Only T H E SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority Vol. LXXI 25th July, 2016 No. 50 Swk. L. N. 204 THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDINANCE THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDER, 2016 (Made under section 3) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Majlis Mesyuarat Kerajaan Negeri by section 3 of the Administrative Areas Ordinance [Cap. 34], the following Order has been made: Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Administrative Areas Order, 2016, and shall be deemed to have come into force on the 1st day of August, 2015. Administrative Areas 2. Sarawak is divided into the divisions, districts and sub-districts specified and described in the Schedule. Revocation 3. The Administrative Areas Order, 2015 [Swk. L.N. 366/2015] is hereby revokedSarawak. Lawnet For Reference Only 26 SCHEDULE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS KUCHING DIVISION (1) Kuching Division Area (Area=4,195 km² approximately) Commencing from a point on the coast approximately midway between Sungai Tambir Hulu and Sungai Tambir Haji Untong; thence bearing approximately 260º 00′ distance approximately 5.45 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.1 kilometres to the junction of Sungai Tanju and Loba Tanju; thence in southeasterly direction along Loba Tanju to its estuary with Batang Samarahan; thence upstream along mid Batang Samarahan for a distance approximately 5.0 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.8 kilometres to the midstream of Loba Batu Belat; thence in westerly direction along midstream of Loba Batu Belat to the mouth of Loba Gong; thence in southwesterly direction along the midstream of Loba Gong to a point on its confluence with Sungai Bayor; thence along the midstream of Sungai Bayor going downstream to a point at its confluence with Sungai Kuap; thence upstream along mid Sungai Kuap to a point at its confluence with Sungai Semengoh; thence upstream following the mid Sungai Semengoh to a point at the midstream of Sungai Semengoh and between the middle of survey peg nos. -

Sarawak Alternative Rural Electrification Scheme)

SARES (Sarawak Alternative Rural Electrification Scheme) Towards Full Electrification Coverage by 2025 Christopher Wesley Ajan, Manager Rural Electrification [email protected] About Sarawak Energy Started in 1921 as a unit in Workforce Public Works Department and 5,000 strong multidisciplinary is now a fully integrated energy team and largest employer of development company and professional Sarawak talent power utility wholly owned by Sarawak Government 75% Largest generator of renewable Serving close to 3 million people energy in Malaysia across largest state in Malaysia. 680,000 accounts covering domestic, commercial, industrial and export customers Lowest tariffs in Malaysia and amongst the lowest in ASEAN To electrify 20,000 more households by 2020 Rural coverage increases to 97% (statewide 99%) Full Electrification by 2025 Categories of un-electrified villages/ Villages Cat. 1 – Grid Connectible 253 Cat. 2 – Grid Possible but Need Access 543 Cat. 3 – Remote Not Grid Connectible 191 Total 987 2009 2017 56% 91% Hybrid/Microgrids + Community Solar Accelerating Rural Electrification Projects • To electrify 20,000 more households by 2020 • Rural coverage increases to 97% (statewide 99%) Expansion of grid infrastructure to rural areas Grid • For villages near to grid and/or more accessible by roads • EHV and MV Substations: 2 EHV and 9 MV substations at strategic locations as reliable sources of energy at rural areas • MV Covered Conductor Lines: 33kV lines connecting main grid to new MV substations at rural locations • RES Last-Miles: HT/LT lines that link up the rural villages to existing grid or new MV substations Stand-alone systems for rural and remotest villages • For those unreachable (not practical or economical) by grid Off-grid infrastructure • Total funding amount of RM 3 billion (USD 750 mil) Grid & Off-grid Project Locations To reach 97% rural and 99% state-wide coverage • Grid-connect 800 villages 11 RPSS & RES • SARES systems for >200 villages A. -

Samarahan, Sarawak Samarahan

Samarahan, Sarawak Samarahan, STB/2019/DivBrochure/Samarahan/V1/P1 JPA, No. 2 Lot 5452, Jalan Datuk Mohammad Musa, 94300 Kota Kota 94300 Musa, Mohammad Datuk Jalan 5452, Lot 2 No. JPA, Address : Address Tel : 082-505911 : Tel 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak Samarahan, Kota 94300 Kampus Institut Kemajuan Desa (INFRA) Cawangan Sarawak Cawangan (INFRA) Desa Kemajuan Institut Kampus Address : Address Wilayah Sarawak Wilayah Institut Tadbiran Awam Negara (INTAN) Kampus Kampus (INTAN) Negara Awam Tadbiran Institut Tel : 082-677 200 082-677 : Tel Jalan Meranek, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak Samarahan, Kota 94300 Meranek, Jalan Address : Address Cawangan Sarawak Cawangan Kampus Institut Kemajuan Desa (INFRA) (INFRA) Desa Kemajuan Institut Kampus Website: ipgmktar.edu.my Website: Fax: 082-672984 Fax: Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) Mara Teknologi Universiti Tel : 083 - 467 121/ 122 Fax : 083 - 467 213 467 - 083 : Fax 122 121/ 467 - 083 : Tel Youth & Sports Sarawak Sports & Youth Tel : 082-673800/082-673700 : Tel Sebuyau District Office District Sebuyau Ministry of Tourism, Arts, Culture, Arts, Tourism, of Ministry Jln Datuk Mohd Musa, Kota Samarahan, 94300 Kuching 94300 Samarahan, Kota Musa, Mohd Datuk Jln Tel : (60) 82 58 1174/ 1214/ 1207/ 1217/ 1032 1217/ 1207/ 1214/ 1174/ 58 82 (60) : Tel Address : Address Jalan Datuk Mohammad Musa, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak Samarahan, Kota 94300 Musa, Mohammad Datuk Jalan Samarahan Administrative Division Administrative Samarahan Address : Address Tel : 082 - 803 649 Fax : 082 - 803 916 803 - 082 : Fax -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

IDF-Report 84 | 1 Dow & Ngiam

IDF International Dragonfly Fund - Report Journal of the International Dragonfly Fund 1-31 Rory A. Dow & Robin W.J. Ngiam Odonata from two areas in the Upper Baram in Sarawak: Sungai Sii and Ulu Moh Published 20.07.2015 84 ISSN 1435-3393 The International Dragonfly Fund (IDF) is a scientific society founded in 1996 for the improvement of odonatological knowledge and the protection of species. Internet: http://www.dragonflyfund.org/ This series intends to publish studies promoted by IDF and to facilitate cost-efficient and rapid dissemination of odonatological data. Editorial Work: Martin Schorr, Milen Marinov Layout: Bernd Kunz Indexed by Zoological Record, Thomson Reuters, UK Home page of IDF: Holger Hunger Impressum: International Dragonfly Fund - Report - Volume 84 Publisher: International Dragonfly Fund e.V., Schulstr. 7B, 54314 Zerf, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] Responsible editor: Martin Schorr Printed by ColourConnection, Frankfurt am Main. www.printweb.de Published: 20.07.2015 Odonata from two areas in the Upper Baram in Sarawak: Sungai Sii and Ulu Moh Rory A. Dow1 & Robin W.J. Ngiam2 1Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands <[email protected]> 2National Biodiversity Centre, National Parks Board, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569, Republic of Singapore <[email protected]> Abstract Records of Odonata from two areas in the upper Baram area in Sarawak’s Miri Division are presented. Sixty five species are recorded from the Sungai Sii area and sixty three from the Ulu Moh area. Notable records include Telosticta ulubaram, Coeliccia south- welli, Leptogomphus new species, Macromia corycia and Tramea cf. -

The Response of the Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol21, No 6, pp 977 – 988, 2000 Globalizationand democratization: the responseo ftheindigenous peoples o f Sarawak SABIHAHOSMAN ABSTRACT Globalizationis amulti-layered anddialectical process involving two consequenttendencies— homogenizing and particularizing— at the same time. Thequestion of howand in whatways these contendingforces operatein Sarawakand in Malaysiaas awholeis therefore crucial in aneffort to capture this dynamic.This article examinesthe impactof globalizationon the democra- tization process andother domestic political activities of the indigenouspeoples (IPs)of Sarawak.It shows howthe democratizationprocess canbe anempower- ingone, thus enablingthe actors to managethe effects ofglobalization in their lives. Thecon ict betweenthe IPsandthe state againstthe depletionof the tropical rainforest is manifested in the form of blockadesand unlawful occu- pationof state landby the former as aform of resistance andprotest. Insome situations the federal andstate governmentshave treated this actionas aserious globalissue betweenthe international NGOsandthe Malaysian/Sarawakgovern- ment.In this case globalizationhas affected boththe nation-state andthe IPs in different ways.Globalization has triggered agreater awareness of self-empow- erment anddemocratization among the IPs. These are importantforces in capturingsome aspects of globalizationat the local level. Globalization is amulti-layered anddialectical process involvingboth homoge- nization andparticularization, ie the rise oflocalism in politics, economics, -

Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission

MALAYSIAN COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA COMMISSION INVITATION TO REGISTER INTEREST AND SUBMIT A DRAFT UNIVERSAL SERVICE PLAN AS A UNIVERSAL SERVICE PROVIDER UNDER THE COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA (UNIVERSAL SERVICE PROVISION) REGULATIONS 2002 FOR THE INSTALLATION OF NETWORK FACILITIES AND DEPLOYMENT OF NETWORK SERVICE FOR THE PROVISIONING OF PUBLIC CELLULAR SERVICES AT THE UNIVERSAL SERVICE TARGETS UNDER THE JALINAN DIGITAL NEGARA (JENDELA) PHASE 1 INITIATIVE Ref: MCMC/USPD/PDUD(01)/JENDELA_P1/TC/11/2020(05) Date: 20 November 2020 Invitation to Register Interest as a Universal Service Provider MCMC/USPD/PDUD(01)/JENDELA_P1/TC/11/2020(05) Page 1 of 142 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................. 4 INTERPRETATION ........................................................................................................................... 5 SECTION I – INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 8 1. BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 8 SECTION II – DESCRIPTION OF SCOPE OF WORK .............................................................. 10 2. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE FACILITIES AND SERVICES TO BE PROVIDED ....................................................................................................................................... 10 3. SCOPE OF -

KKM HEADQUARTERS Division / Unit Activation Code PEJABAT Y.B. MENTERI 3101010001 PEJABAT Y.B

KKM HEADQUARTERS Division / Unit Activation Code PEJABAT Y.B. MENTERI 3101010001 PEJABAT Y.B. TIMBALAN MENTERI 3101010002 PEJABAT KETUA SETIAUSAHA 3101010003 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA SETIAUSAHA (PENGURUSAN) 3101010004 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA SETIAUSAHA (KEWANGAN) 3101010005 PEJABAT KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN 3101010006 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN (PERUBATAN) 3101010007 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN (KESIHATAN AWAM) 3101010008 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN (PENYELIDIKAN DAN SOKONGAN TEKNIKAL) 3101010009 PEJABAT PENGARAH KANAN (KESIHATAN PERGIGIAN) 3101010010 PEJABAT PENGARAH KANAN (PERKHIDMATAN FARMASI) 3101010011 PEJABAT PENGARAH KANAN (KESELAMATAN DAN KUALITI MAKANAN) 3101010012 BAHAGIAN AKAUN 3101010028 BAHAGIAN AMALAN DAN PERKEMBANGAN FARMASI 3101010047 BAHAGIAN AMALAN DAN PERKEMBANGAN KESIHATAN PERGIGIAN 3101010042 BAHAGIAN AMALAN PERUBATAN 3101010036 BAHAGIAN DASAR DAN HUBUNGAN ANTARABANGSA 3101010019 BAHAGIAN DASAR DAN PERANCANGAN STRATEGIK FARMASI 3101010050 BAHAGIAN DASAR DAN PERANCANGAN STRATEGIK KESIHATAN PERGIGIAN 3101010043 BAHAGIAN DASAR PERANCANGAN STRATEGIK DAN STANDARD CODEX 3101010054 BAHAGIAN KAWALAN PENYAKIT 3101010030 BAHAGIAN KAWALAN PERALATAN PERUBATAN 3101010055 BAHAGIAN KAWALSELIA RADIASI PERUBATAN 3101010041 BAHAGIAN KEJURURAWATAN 3101010035 BAHAGIAN KEWANGAN 3101010026 BAHAGIAN KHIDMAT PENGURUSAN 3101010023 BAHAGIAN PEMAKANAN 3101010033 BAHAGIAN PEMATUHAN DAN PEMBANGUNAN INDUSTRI 3101010053 BAHAGIAN PEMBANGUNAN 3101010020 BAHAGIAN PEMBANGUNAN KESIHATAN KELUARGA 3101010029 BAHAGIAN -

Mill List - 2020

General Mills - Mill List - 2020 General Mills July 2020 - December 2020 Parent Mill Name Latitude Longitude RSPO Country State or Province District UML ID 3F Oil Palm Agrotech 3F Oil Palm Agrotech 17.00352 81.46973 No India Andhra Pradesh West Godavari PO1000008590 Aathi Bagawathi Manufacturing Abdi Budi Mulia 2.051269 100.252339 No Indonesia Sumatera Utara Labuhanbatu Selatan PO1000004269 Aathi Bagawathi Manufacturing Abdi Budi Mulia 2 2.11272 100.27311 No Indonesia Sumatera Utara Labuhanbatu Selatan PO1000008154 Abago Extractora Braganza 4.286556 -72.134083 No Colombia Meta Puerto Gaitán PO1000008347 Ace Oil Mill Ace Oil Mill 2.91192 102.77981 No Malaysia Pahang Rompin PO1000003712 Aceites De Palma Aceites De Palma 18.0470389 -94.91766389 No Mexico Veracruz Hueyapan de Ocampo PO1000004765 Aceites Morichal Aceites Morichal 3.92985 -73.242775 No Colombia Meta San Carlos de Guaroa PO1000003988 Aceites Sustentables De Palma Aceites Sustentables De Palma 16.360506 -90.467794 No Mexico Chiapas Ocosingo PO1000008341 Achi Jaya Plantations Johor Labis 2.251472222 103.0513056 No Malaysia Johor Segamat PO1000003713 Adimulia Agrolestari Segati -0.108983 101.386783 No Indonesia Riau Kampar PO1000004351 Adimulia Agrolestari Surya Agrolika Reksa (Sei Basau) -0.136967 101.3908 No Indonesia Riau Kuantan Singingi PO1000004358 Adimulia Agrolestari Surya Agrolika Reksa (Singingi) -0.205611 101.318944 No Indonesia Riau Kuantan Singingi PO1000007629 ADIMULIA AGROLESTARI SEI TESO 0.11065 101.38678 NO INDONESIA Adimulia Palmo Lestari Adimulia Palmo Lestari -

Factors Associated with Emergence and Spread of Cholera Epidemics and Its Control in Sarawak, Malaysia Between 1994 and 2003

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 43, No. 2, September 2005 Factors Associated with Emergence and Spread of Cholera Epidemics and Its Control in Sarawak, Malaysia between 1994 and 2003 * ** ** Patrick Guda BENJAMIN , Jurin Wolmon GUNSALAM , Son RADU , *** ** # ## Suhaimi NAPIS , Fatimah Abu BAKAR , Meting BEON , Adom BENJAMIN , ### * † Clement William DUMBA , Selvanesan SENGOL , Faizul MANSUR , † †† ††† Rody JEFFREY , NAKAGUCHI Yoshitsugu and NISHIBUCHI Mitsuaki Abstract Cholera is a water and food-borne infectious disease that continues to be a major public health problem in most Asian countries. However, reports concerning the incidence and spread of cholera in these countries are infrequently made available to the international community. Cholera is endemic in Sarawak, Malaysia. We report here the epidemiologic and demographic data obtained from nine divisions of Sarawak for the ten years from 1994 to 2003 and discuss factors associated with the emergence and spread of cholera and its control. In ten years, 1672 cholera patients were recorded. High incidence of cholera was observed during the unusually strong El Niño years of 1997 to 1998 when a very severe and prolonged drought occurred in Sarawak. Cholera is endemic in the squatter towns and coastal areas especially those along the Sarawak river estuaries. The disease subsequently spread to the rural settlements due to movement of people from the towns to the rural areas. During the dry seasons when tributary gravity fed tap waters cease to flow, rural communities rely on river water for domestic use for consumption, washing clothes and household utensils. Consequently, these practices facilitated the spread of water borne diseases such as cholera. The epidemiologic and demographic data were categorized according to ethnic group, gender, occupation, and age of the patients. -

Usp Register

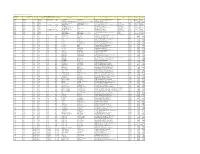

SURUHANJAYA KOMUNIKASI DAN MULTIMEDIA MALAYSIA (MALAYSIAN COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA COMMISSION) USP REGISTER July 2011 NON-CONFIDENTIAL SUMMARIES OF THE APPROVED UNIVERSAL SERVICE PLANS List of Designated Universal Service Providers and Universal Service Targets No. Project Description Remark Detail 1 Telephony To provide collective and individual Total 89 Refer telecommunications access and districts Appendix 1; basic Internet services based on page 5 fixed technology for purpose of widening communications access in rural areas. 2 Community The Community Broadband Centre 251 CBCs Refer Broadband (CBC) programme or “Pusat Jalur operating Appendix 2; Centre (CBC) Lebar Komuniti (PJK)” is an nationwide page 7 initiative to develop and to implement collaborative program that have positive social and economic impact to the communities. CBC serves as a platform for human capital development and capacity building through dissemination of knowledge via means of access to communications services. It also serves the platform for awareness, promotional, marketing and point- of-sales for individual broadband access service. 3 Community Providing Broadband Internet 99 CBLs Refer Broadband access facilities at selected operating Appendix 3; Library (CBL) libraries to support National nationwide page 17 Broadband Plan & human capital development based on Information and Communications Technology (ICT). Page 2 of 98 No. Project Description Remark Detail 4 Mini Community The ultimate goal of Mini CBC is to 121 Mini Refer Broadband ensure that the communities living CBCs Appendix 4; Centre within the Information operating page 21 (Mini CBC) Departments’ surroundings are nationwide connected to the mainstream ICT development that would facilitate the birth of a society knowledgeable in the field of communications, particularly information technology in line with plans and targets identified under the National Broadband Initiatives (NBI). -

Title Factors Associated with Emergence and Spread of Cholera

Factors Associated with Emergence and Spread of Cholera Title Epidemics and Its Control in Sarawak, Malaysia between 1994 and 2003 Benjamin, Patrick Guda; Gunsalam, Jurin Wolmon; Radu, Son; Napis, Suhaimi; Bakar, Fatimah Abu; Beon, Meting; Benjamin, Author(s) Adom; Dumba, Clement William; Sengol, Selvanesan; Mansur, Faizul; Jeffrey, Rody; Nakaguchi, Yoshitsugu; Nishibuchi, Mitsuaki Citation 東南アジア研究 (2005), 43(2): 109-140 Issue Date 2005-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/53820 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 43, No. 2, September 2005 Factors Associated with Emergence and Spread of Cholera Epidemics and Its Control in Sarawak, Malaysia between 1994 and 2003 * ** ** Patrick Guda BENJAMIN , Jurin Wolmon GUNSALAM , Son RADU , *** ** # ## Suhaimi NAPIS , Fatimah Abu BAKAR , Meting BEON , Adom BENJAMIN , ### * † Clement William DUMBA , Selvanesan SENGOL , Faizul MANSUR , † †† ††† Rody JEFFREY , NAKAGUCHI Yoshitsugu and NISHIBUCHI Mitsuaki Abstract Cholera is a water and food-borne infectious disease that continues to be a major public health problem in most Asian countries. However, reports concerning the incidence and spread of cholera in these countries are infrequently made available to the international community. Cholera is endemic in Sarawak, Malaysia. We report here the epidemiologic and demographic data obtained from nine divisions of Sarawak for the ten years from 1994 to 2003 and discuss factors associated with the emergence and spread of cholera and its control. In ten years, 1672 cholera patients were recorded. High incidence of cholera was observed during the unusually strong El Niño years of 1997 to 1998 when a very severe and prolonged drought occurred in Sarawak. Cholera is endemic in the squatter towns and coastal areas especially those along the Sarawak river estuaries.