Player's Option™

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arctic Exploration and the Explorers of the Past

st.olafWiNtEr 2013 GLOBAL CITIZENS GOING TO EXTREMES OLE INNOVATORS ON ThE COvER: Vanessa trice Peter ’93 in the Los Angeles studio of paper artist Anna Bondoc. PHOtO By nAnCy PAStOr / POLAriS ST. OLAF MAGAzINE WINTER 2013 volume 60 · No. 1 Carole Leigh Engblom eDitOr Don Bratland ’87, holmes Design Art DireCtOr Laura hamilton Waxman COPy eDitOr Suzy Frisch, Joel hoekstra ’92, Marla hill holt ’88, Erin Peterson, Jeff Sauve, Kyle Schut ’13 COntriButinG writerS Fred J. Field, Stuart Isett, Jessica Brandi Lifl and, Mike Ludwig ’01, Kyle Obermann ’14, Nancy Pastor, Tom Roster, Chris Welsch, Steven Wett ’15 COntriButinG PHOtOGrA PHerS st. olaf Magazine is published three times annually (winter, Spring, Fall) by St. Olaf College, with editorial offi ces at the Offi ce of Marketing and Com- 16 munications, 507-786-3032; email: [email protected] 7 postmaster: Send address changes to Data Services, St. Olaf College, 1520 St. Olaf Ave., Northfi eld, MN 55057 readers may update infor- mation online: stolaf.edu/alumni or email alum-offi [email protected]. Contact the Offi ce of Alumni and Parent relations, 507- 786-3028 or 888-865-6537 52 Class Notes deadlines: Spring issue: Feb. 1 Fall issue: June 1 winter issue: Oct. 1 the content for class notes originates with the Offi ce of Alumni and Parent relations and is submitted to st. olaf Magazine, which reserves the right to edit for clarity and space constraints. Please note that due to privacy concerns, inclusion is at the discretion of the editor. www.stolaf.edu st.olaf features Global Citizens 7 By MArLA HiLL HOLt ’88 St. -

Frank Zappa and His Conception of Civilization Phaze Iii

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2018 FRANK ZAPPA AND HIS CONCEPTION OF CIVILIZATION PHAZE III Jeffrey Daniel Jones University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2018.031 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jones, Jeffrey Daniel, "FRANK ZAPPA AND HIS CONCEPTION OF CIVILIZATION PHAZE III" (2018). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 108. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/108 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Alcon 'S Lair: Level 1 ~H

~alcon 's laiR: level 1 ~h. Sample file ~-2~ Edition Falcon master credits Table of contents Design: Richard W. and Anne Brown Editing: C. Terry Phillips Introduction . ... ..... .. ... .. ... ... ......2 Cover Art: Ken Frank Chapter 1: The Game is Afoot . ................4 Interior Art: Ken Frank Cartography: Dave Sutherland Chapter 2: An Ancient Mystery ......... .......9 Fold-ups: Dave Sutherland Typograp hy: Gaye O'Keefe Chapter 3: Into the Wilderness ................. 19 Keylining: Paul Hanchette Chapter 4: Anybody Home? ...................27 «>1990 TSR Inc. All Rtghu Reserved. Chapter 5: "Master" Falcon? .............. ... 43 Primed in the U.S.A. Chapter 6: The Counterattack ................. .49 ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS. AD&D, WORLD OF GREYHAWK and GREY HAWK are registered trademarks owned by Chapter 7: Finale ................. .......... 53 TSR, Inc. Non-Player Characters ........................ 56 PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. New Magic .............. ........... .. .....60 Distributed to the book trade in the United States New Monster ........................... .. 61 by Random House, Inc .. and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the New Monster ................ ...... .... .. 62 toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. Distributed in the United Kingdom by TSR UK New Monster ......................... ..... 63 Ltd. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or ocher unauthorized use of the material or arrwork coma~ ned herean is prohibited without the express wriuen permisston of TSR , Inc. TSR, Inc. TSR Ltd. POB756 120 Church End, Lake Geneva, Cherry Hinton WI 53147 Cambridge CB 1 3LB USA SampleUnited Kingdom file 9289 ISBN 0-88038-852-8 Introduction Notes for the Dungeon phere of the adventure and to Wealthy neighborhood adapt it to his own campaign and Marketplace Master his players' styles. -

Cult of the Dragon

Cult of the Dragon by Dale Donovan And naught will be left save shuttered thrones with no rulers. But the dead dragons shall rule the world entire, and . Sammaster First-Speaker Founder of the Cult of the Dragon Dedication To my mother and my father, who always encouraged me, no matter how seemingly strange my interests may have appeared. Thanks to you both I had the chance to pursueand obtainmy dream. While it may seem curious to dedicate a book about a bunch of psycho cultists to ones parents, I figured that, of all people, you two would understand. Credits Design: Dale Donovan Additional and Original Design: L. Richard Baker III, Eric L. Boyd, Timothy B. Brown, Monte Cook, Nigel Findley, Ed Greenwood, Lenard Lakofka, David Kelman, Bill Muhlhausen, Robert S. Mullin, Bruce Nesmith, Jeffrey Pettengill, Jon Pickens, and James M. Ward Development & Editing: Julia Martin Cover Illustration: Clyde Caldwell Interior Illustrations: Glen Michael Angus Art Direction: Dana Knutson and Dawn Murin Typesetting: Angelika Lokotz Research, Inspiration, & Additional Contributions: Robert L. Nichols & Craig Sefton Special Acknowledgment: Gregory Detwiler, Ed Greenwood, Jamie Nossal, Cindy Rick, Carl Sargent, Steven Schend, and the stories of Clark Ashton Smith & Edgar Allan Poe Campaign setting based on the original game world of Ed Greenwood. Based on the original DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® rules created by E. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson. ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, AD&D, DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, DUNGEON MASTER, FORGOTTEN REALMS, MONSTROUS COMPENDIUM, PLAYERS OPTION, and the TSR logo are registered trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. COUNCIL OF WYRMS, ENCYCLOPEDIA MAGICA, and MONSTROUS MANUAL are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

The Highbank Forest

The Highbank Forest A last important factor in the effort to build this community A Settlement of Elves in the Vast centered around a dangerous adventure the Coronal and some By Kenn Boyle and Rick Brill trusted Elves of the area undertook. Delving into the depths of Converted by Aaron Martin and Joe Harney the Underdark, this group was beset upon by a force of Drow and minions of overwhelming power. Forced to flee, the group of Located just two days north and east of the city of Ravens Bluff, Tel’Quessir used powerful magic to flee to the one place no the Highbank Forest has become the center of Elven culture in servant of Lolth would follow, the Elven Realm of Arvandor. This the Vast. Under the patronage of the Tulani Lord Glantherius of trip changed the lives and focus of most all the Elves there, Arvandor, the leadership of Coronal Semmitsaul Silverspear, redefining their views of and roles in the world. Most importantly, and the guidance of the Highbank Council, the Forest has the new settlement in the Highbank Forest gained the blessing of flourished. They strive to make the Forest a better place for the a powerful Eladrin Clan from Arvandor. Their leader, a legendary Elven people and the sylvan races. Eladrin Tulani Lord known as Glantherius offered the Highbank Elves a place in Clan Calarrii, and promised to be a voice of The Highbank Forest is a community established by Elves and assistance and wisdom for their task ahead. He praised their for Elves, to sustain the Elven way of life. -

Dragon Magazine #180

SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS AD&D Trading Cards TSR staff Issue # 180 Insert Your preview of the 1992 series is here in this issue! Vol. XVI, No. 11 April 1992 OTHER FEATURES Publisher Not Quite the Frontispiece Ken Widing James M. Ward 9 Our April Fools section wandered off. Just enjoy. Suspend Your Disbelief! Tanith Tyrr Editor 10 Maybe its fantasy, but your campaign must still make sense! Roger E. Moore Not Another Magical Sword!?! Charles Rodgers Fiction editor 14 Why own just any old magical sword when you can own a legend? Barbara G. Young Role-playing Reviews Rick Swan 18 A good day for the thought police: three supplements on psionics. Associate editor Dale A. Donovan Your Basic Barbarian Lee A. Spain 24 So your fighter has a 6 intelligence. Make the most of it. Editorial assistant Wolfgang H. Baur Hot Night in the Old Town Joseph R. Ravitts 28 If your cleric thinks his home life is dull, wait till the DM sees this! Art director Colorful Connection Raymond C. Young Larry W. Smith 34 Whats the puzzle within this puzzle? A fantasy crossword for gamers. Production staff The Voyage of the Princess Ark Bruce A. Heard Gaye OKeefe Angelika Lokotz 41 What happens when a D&D® game character dies? Tracey Zamagne Mary Chudada Your Own Treasure Hunt Robin Rist 52 When funds run low in your gaming club, its time for a fund-raising Subscriptions adventure. Janet L. Winters The Role of Computers Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser U.S. advertising 57 A visit with Dr. Brain, Elvira, and the Simpsons. -

So What's It Called, Anyway?

SO WHAT’S IT CALLED, ANYWAY? A Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Compatible GM’S RESOURCE by Marc Radle Sample file Sample file SO WHAT’S IT CALLED, ANYWAY? A Pathfinder Roleplaying Game GM’S RESOURCE supplement by Marc Radle Having returned from their most recent adventure, the PCs rest and recuperate in a nearby town. Of course, being adventurers it’s not long before they start to explore every nook and cranny of their new home in search of adventure! Before the hard‐worked GM knows it, they are exploring every un‐detailed portion of the town and asking questions like “So what’s that tavern called, anyway?” Instead of panicking, or using the same old names again and again, a GM using the tables within can quickly name dozens (if not hundreds) of taverns, inns, shops, locations and even other organisations and groups. Alternatively, the GM can use these tables ahead of time to create interesting and evocative names to pique the PCs’ interest and to breathe life into his campaign setting. Sample file C REDITS A BOUT THE D ESIGNER Design: Marc Radle Marc Radle is a professional graphic artist and designer by trade. Development: Creighton Broadhurst He is married and has three kids (one teenaged son and two very Editing: Creighton Broadhurst spoiled cats). Cover Design: Creighton Broadhurst He started playing D&D in the late 70’s – good old First Layout: Creighton Broadhurst Edition AD&D! He also played many other RPGs back then… Interior Artists: Marc Radle Marvel Superheroes, Champions, Elfquest, FASA's Star Trek, Star Frontiers, the list goes on…but it always came back to AD&D! Thank you for purchasing So What’s It Called, Anyway?; we hope Marc faded out of gaming sometime after 2nd Edition came out you enjoy it and that you check out our other fine print and PDF – partially because 2nd Edition just didn't quite do it for him but products. -

Paladin's Handbook

ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® 2nd Edition Player’s Handbook Rules Supplement The Complete Paladin’s Handbook by Rick Swan CREDITS Design: Rick Swan Editing: Allen Varney Black and White Art: Ken Frank, Mark Nelson, Valerie Valusek Color Art: Les Dorscheid, Fred Fields, L. Dean James, Glen Orbik Electronic Prepress Coordination: Tim Coumbe Typography: Angelika Lokotz Production: Paul Hanchette TSR, Inc. TSR Ltd. 201 Sheridan Springs Rd. 120 Church End, Lake Geneva, Cherry Hinton WI 53147 Cambridge CB1 3LB USA United Kingdom ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, AD&D, DUNGEON MASTER and DRAGONLANCE are registered trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. The TSR logo is a trademark owned by TSR, Inc. This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of TSR, Inc. Distributed to the book and hobby trade in the United Kingdom by TSR Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. © 1994 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. Table of Contents Introduction Chapter 1: Character Creation Paladin Requirements Level Advancement Armor and Weapons Clerical Magic Chapter 2: Paladin Abilities Detect Evil Intent Saving-Throw Bonus Immunity to Disease Cure Diseases Laying On Hands Aura of Protection Holy Sword Turning Undead Bonded Mount Clerical Spells Chapter 3: Ethos Strictures Edicts Virtues Code of Ennoblement Violations and Penalties Chapter 4: Paladin Kits Acquiring Kits -

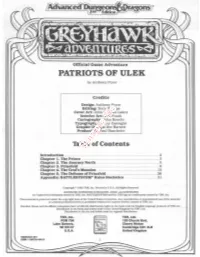

Patriots of Ulek

by Anthony Pryor Credits Design: Anthony Pryor Editing: Terry Phillips Cover Art: John & Laura Lakey Interior Art: Ken Frank Cartography: John Knecht Typography: Bacey Zamagne Graphic Design: Dee Barnett Production: Paul Hanchette ThbleSample of Contents file Introduction ............................................. 2 Chapter1.ThePrince ..................................... 3 Chapter 2. The Journey North ............................. .5 Chapter 3. Prinzfeld ..................................... .9 Chapter 4. The Grafs Mansion ............................ 13 Chapter 5. The Defense of Prinzfeld ....................... .26 Appendix: BATTLESYSTEM"'Rules Statistics ...............3 1 Copyright 1992 TSR, Inc. Printed in USA. All Rights Reserved. ADVANCED DUNGEONS &DRAGONS,AD&D. and GREYHAWK are registered trademarks owned by TSR. Inc. BATTLESYSTEM and the TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork presented herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR. Inc. Random House and its affiliate companies have worldwide distribution rights in the book trade for English language products of TSR, Inc. Distributed to the book and hobby trade in the United Kingdom by TSR, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. 120 Church End, Lake Geneva, Cherry Hinton WI 53147 Cambridge CBI 3LB United Kingdom 9385XXX1401 ISBN 1-56076-4494 1 masters. Boxed text may be read to the play- Introduction ers to give them important information or de- scribe the things they see. DMs are not Darkness has descended upon the world of required to read this text as written if they Greyhawk. All across the Flanaess, the forces wish to change the encounter. -

Dragon Magazine #217

Issue #217 Vol. XIX, No. 12 May 1995 Publisher TSR, Inc. Associate Publisher Brian Thomsen SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS Editor-in-Chief Boons & Benefits Larry Granato Kim Mohan 10 Compensate your PCs with rewards far more Associate editor valuable than mere cash or jewels. Dale A. Donovan Behind Enemy Lines Phil Masters Fiction editor 18 The PCs are trapped in hostile territory with an Barbara G. Young entire army chasing them. Sounds like fun, doesnt it? Editorial assistant Two Heads are Better than One Joshua Siegel Wolfgang H. Baur 22 Michelle Vuckovich Split the game masters chores between two people. Art director Class Action Peter C. Zelinski Larry W. Smith 26 How about a party of only fighters, thieves, clerics, or mages? Production Renee Ciske Tracey Isler REVIEWS Subscriptions Janet L. Winters Eye of the Monitor Jay & Dee 65 Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. U.S. advertising Cindy Rick The Role of Books John C. Bunnell 86 Delve into these faerie tales for all ages. U.K. correspondent and U.K. advertising Carolyn Wildman DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 1062-2101) is published Magazine Marketing, Tavistock Road, West Drayton, monthly by TSR, inc., 201 Sheridan Springs Road, Middlesex UB7 7QE, United Kingdom; telephone: Lake Geneva WI 53147, United States of America. The 0895-444055. postal address for all materials from the United States Subscriptions: Subscription rates via second-class of America and Canada except subscription orders is: mail are as follows: $30 in U.S. funds for 12 issues DRAGON® Magazine, 201 Sheridan Springs Road, sent to an address in the U.S.; $36 in U.S. -

Dragon Magazine #236

The dying game y first PC was a fighter named Random. I had just read “Let’s go!” we cried as one. Roger Zelazny’s Nine Princes in Amber and thought that Mike held up the map for us to see, though Jeff and I weren’t Random was a hipper name than Corwin, even though the lat- allowed to touch it. The first room had maybe ten doors in it. ter was clearly the man. He lasted exactly one encounter. Orcs. One portal looked especially inviting, with multi-colored veils My second PC was a thief named Roulette, which I thought drawn before an archway. I pointed, and the others agreed. was a clever name. Roulette enjoyed a longer career: roughly “Are you sure you want to go there?” asked Mike. one session. Near the end, after suffering through Roulette’s “Yeah. I want a vorpal sword,” I said greedily. determined efforts to search every 10’-square of floor, wall, and “It’s the most dangerous place in the dungeon,” he warned. ceiling in the dungeon, Jeff the DM decided on a whim that the “I’ll wait and see what happens to him,” said Jeff. The coward. wall my thief had just searched was, in fact, coated with contact “C’mon, guys! If we work together, we can make it.” I really poison. I rolled a three to save. wanted a vorpal sword. One by one they demurred, until I Thus ensued my first player-DM argument. There wasn’t declared I’d go by myself and keep all the treasure I found.