UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metodología Y Evaluación De Las Tipificaciones Municipales

DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DEL REGISTRO FEDERAL DE ELECTORES METODOLOGÍA Y EVALUACIÓN DE LAS TIPIFICACIONES MUNICIPALES junio de 2015 Página 1 de 12 Contenido 1. Introducción 2. El algoritmo para buscar la tipificación municipal 3. Tipificación municipal de Sinaloa 4. Reglas para evaluar la tipificación municipal Página 2 de 12 Introducción Con base en los Criterios que serán considerados para la Distritación local de cada una de las entidades federativas, dos de las variables que deberán tomarse en cuenta son el equilibrio poblacional y la integridad municipal, donde se indica que: Se busca que el equilibrio poblacional garantice una mejor distribución en la determinación del número de personas por cada distrito en las entidades federativas. El criterio de integridad municipal establece que se deberán de construir preferentemente distritos con municipios completos o en su caso con territorio de un solo municipio. Sin embargo estas dos variables difícilmente encuentran convergencia ya que el equilibrio poblacional idóneo, en general, va en detrimento de la integridad municipal. Es por esto que como un trabajo previo a la aplicación del sistema, se busca identificar, tanto a los municipios que permitan conformar distritos completos a su interior, así como a aquellos agrupamientos municipales que favorezcan la conformación de distritos que consideren las dos variables antes mencionadas. Para lo cual se empleó el siguiente algoritmo: Algoritmo para encontrar la Tipología Municipal de una Entidad 1. Obtener la población total del estado, 푃푇. 2. Obtener el número de distritos en que se partirá el estado, 푛. 푃 3. Calcular la media poblacional estatal 푃 = 푇 . 푀 푛 푃푗 4. -

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long Lat Durango Canelas EL PUERTO DEL AGUA 1062914 250413 Durango Canelas LA ESPERANZA 1062624 250517 Durango Canelas TIERRA AZUL 1063131 250513 Durango Tamazula ACACHUANE 1065724 250032 Durango Tamazula ACATITA GRANDE (ACATITA) 1070241 245957 Durango Tamazula ACATITÁN 1065314 245515 Durango Tamazula AGUA CALIENTE 1065409 245957 Durango Tamazula AMACUABLE 1065346 250120 Durango Tamazula ARROYO GRANDE DE MATAVACAS 1064810 245810 Durango Tamazula ARROYO SECO 1070229 250917 Durango Tamazula ARROYO VERDE (LOS TOROS) 1070501 251322 Durango Tamazula BOCA DE ARROYO DEL ZAPOTE 1070928 251937 Durango Tamazula CARRICITOS 1064943 245009 Durango Tamazula CARRICITOS 1070249 251420 Durango Tamazula CHACALA 1064419 244842 Durango Tamazula CHACOAL 1065650 250231 Durango Tamazula CHAPOTÁN 1065205 245646 Durango Tamazula COLOMA 1065530 245655 Durango Tamazula COLOMITA 1065621 245546 Durango Tamazula EL AGUAJE 1065350 245840 Durango Tamazula EL ARRAYANAL 1064818 250134 Durango Tamazula EL AYALI 1070620 251752 Durango Tamazula EL BARCO 1070521 251743 Durango Tamazula EL BLEDAL 1065306 250318 Durango Tamazula EL CARRIZAL 1065546 245836 Durango Tamazula EL CASTILLO 1065638 245802 Durango Tamazula EL CHILAR 1065806 251056 Durango Tamazula EL FILTRO 1070118 250911 Durango Tamazula EL FRIJOLAR 1065030 250228 Durango Tamazula EL GACHUPÍN 1065149 245910 Durango Tamazula EL GALERÓN 1070501 251506 Durango Tamazula EL GATO 1065744 251410 Durango Tamazula EL GUAMUCHILAR 1070548 251742 Durango Tamazula EL GUAMUCHILITO 1064542 244741 Durango -

716* Ley De Gobierno Municipal

1 TEXTO VIGENTE Última reforma publicada P.O. No. 020 del 12 de febrero de 2018. DECRETO NÚMERO: 716* LEY DE GOBIERNO MUNICIPAL DEL ESTADO DE SINALOA CAPÍTULO I DISPOSICIONES GENERALES Artículo 1. La presente Ley es reglamentaria del Título Quinto de la Constitución Política del Estado de Sinaloa; sus disposiciones son de orden público e interés social, de observancia y aplicación general y tienen por objeto establecer las bases generales para el gobierno y la administración pública municipal. Artículo 2. El municipio como orden de gobierno local, se establece con la finalidad de organizar a la comunidad asentada en su territorio en la gestión de sus intereses y ejercer las funciones y prestar los servicios que esta requiera, de conformidad con lo establecido por la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos y la Constitución Política del Estado de Sinaloa. Artículo 3. Los municipios de Sinaloa gozan de autonomía plena para gobernar y administrar sin interferencia de otros poderes, los asuntos propios de la comunidad. En ejercicio de esta atribución, estarán facultados para aprobar y expedir los reglamentos, bandos de policía y gobierno, disposiciones administrativas y circulares de observancia general dentro de su jurisdicción territorial, así como para: I. Regular el funcionamiento del ayuntamiento y de la administración pública municipal, así como establecer sus órganos de gobierno interno; II. Establecer los procedimientos para el nombramiento y remoción de los servidores públicos; III. Regular las materias, procedimientos, funciones y servicios públicos de su competencia; IV. Regular el uso y aprovechamiento de los bienes municipales; y V. Emitir el Reglamento que señale las demarcaciones que para efectos administrativos se establezcan en el territorio municipal. -

Yu-Feng Hsu and Jerry A. Powell

Phylogenetic Relationships within Heliodinidae and Systematics of Moths Formerly Assigned to Heliodines Stainton (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutoidea) Yu-Feng Hsu and Jerry A. Powell Phylogenetic Relationships within Heliodinidae and Systematics of Moths Formerly Assigned to Heliodines Stainton (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutoidea) Yu-Feng Hsu and Jerry A. Powell UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley • Los Angeles • London UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN ENTOMOLGY Editorial Board: Penny Gullan, Bradford A. Hawkins, John Heraty, Lynn S. Kimsey, Serguei V. Triapitsyn, Philip S. Ward, Kipling Will Volume 124 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, LTD. LONDON, ENGLAND © 2005 BY THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hsu, Yu-Feng, 1963– Phylogenetic relationships within Heliodinidae and systematics of moths formerly assigned to Heliodines Stainton (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutoidea) / Yu-Feng Hsu and Jerry A. Powell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-520-09847-1 (paper : alk. paper) — (University of California publications in entomology ; 124) 1. Heliodinidae—Classification. 2. Heliodinidae—Phylogeny. I. Title. II. Series. QL561.H44 H78 595.78 22—dc22 2004058800 Manufactured in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). Contents Acknowledgments, ix Abstract, xi Introduction ...................................................... 1 Problems in Systematics of Heliodinidae and a Historical Review ............ 4 Material and Methods ............................................ 6 Specimens and Depositories, 6 Dissections and Measurements, 7 Wing Venation Preparation, 7 Scanning Electron Microscope Preparation, 8 Species Discrimination and Description, 8 Larval Rearing Procedures, 8 Phylogenetic Methods, 9 Phylogeny of Heliodinidae ........................................ -

OECD Territorial Grids

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES DES POLITIQUES MEILLEURES POUR UNE VIE MEILLEURE OECD Territorial grids August 2021 OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities Contact: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Territorial level classification ...................................................................................................................... 3 Map sources ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Map symbols ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Disclaimers .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Australia / Australie ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Austria / Autriche ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium / Belgique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ...................................................................................................................................................... -

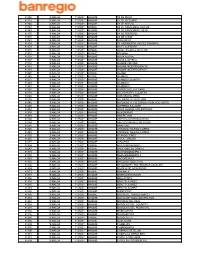

81236 Sinaloa 7125001 Ahome 10 De Mayo 81271 Sinaloa 7125001 Ahome 12 De Octubre 81360 Sinaloa 7125001 Ahome 18 De Marzo 81363 S

81236 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME 10 DE MAYO 81271 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME 12 DE OCTUBRE 81360 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME 18 DE MARZO 81363 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME 20 DE NOVIEMBRE NUEVO 81363 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME 20 DE NOVIEMBRE VIEJO 81375 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME 24 DE FEBRERO 81238 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME 28 DE JUNIO 81361 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME 5 DE MAYO 81234 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME 75 (HERIBERTO VALDEZ ROMERO) 81379 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME 9 DE DICIEMBRE 81238 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ADOLFO LOPEZ MATEOS 81372 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ADUANA 81303 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME AGUA NUEVA 81307 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME AGUILA AZTECA 81315 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME AHOME CENTRO 81318 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME AHOME INDEPENDENCIA 81318 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME AHOME INDEPENDIENTE 81248 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALAMO 81248 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALAMOS 81271 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALAMOS COUNTRY 81248 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALAMOS I 81248 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALAMOS II 81367 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALBERGUE LOUISIANA 81278 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALCAZAR DEL COUNTRY 81260 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALEJANDRO PEÑA 81236 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALFONSO G CALDERON 81346 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALFONSO G. CALDERON (POBLADO SIETE) 81240 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALFREDO SALAZAR 81240 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALMA GUADALUPE ESTRADA 81294 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ALMENDRAS 81289 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME AMERICANA 81290 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME AMPLIACION BUROCRATA 81294 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME AMPLIACION NUEVO SIGLO 81280 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ANAHUAC 81320 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME ANTONIO TOLEDO CORRO 81285 SINALOA 7125001 AHOME -

Martes 09 De Febrero 2021 Actualización #Covid19 Sinaloa

⚠Martes 09 de Febrero 2021⚠ Actualización #Covid19 � Sinaloa * Día 348 desde el primer caso detectado* * HAY 97 NUEVOS * De: Culiacán 27 El Fuerte 4 Mazatlán 22 Mocorito 2 Ahome 20 Angostura 2 Guasave 6 Elota 2 Salvador Alvarado 6 Cosalá 1 Navolato 5 *Pacientes Activos* 741 Se han *recuperado 26,133*, 106 nuevos De Culiacán 67 Ahome 5 Mazatlán 10 Rosario 5 El Fuerte 8 Elota 3 Salvador Alvarado 5 Choix 3 15 nuevos fallecimientos reportados en las últimas 24 horas De Culiacán 3 Elota 1 Mazatlán 2 Cosalá 1 Guasave 2 Angostura 1 Ahome 2 El Fuerte 1 Choix 1 Navolato 1 HOSPITALIZADOS EL 31.5% DE LOS PACIENTES ACTIVOS DISPONIBLES 68% DE LAS CAMAS COVID EN EL ESTADO *Pacientes Activos Por Municipio* CULIACÁN: 395 MOCORITO: 6 AHOME: 123 ELOTA: 5 MAZATLÁN: 87 BADIRAGUATO: 4 GUASAVE: 46 ROSARIO: 3 SALVADOR ALVARADO: 19 ESCUINAPA: 2 SINALOA: 16 SAN IGNACIO: 1 NAVOLATO: 13 CONCORDIA: 1 EL FUERTE: 10 CHOIX: 1 ANGOSTURA: 9 COSALA: 0 SOSPECHOSOS EN TODO SINALOA *EXCEPTO SAN IGNACIO, ESCUINAPA Y CONCORDIA* *TOTAL DE RECUPERADOS: *TOTAL DE MUERTES: *CASOS SOSPECHOSOS 26,133* 4,751* 811* 11,377 CULIACÁN 1,659 CULIACAN 331 CULIACÁN 4,121 MAZATLÁN 895 AHOME 177 AHOME 3,626 GUASAVE 725 MAZATLAN 125 GUASAVE 3,327 AHOME 580 GUASAVE 73 MAZATLÁN 929 SALVADOR ALVARADO 187 SALVADOR ALVARADO 36 NAVOLATO 741 NAVOLATO 161 NAVOLATO 15 ROSARIO 345 SINALOA 118 EL FUERTE 14 SINALOA 300 ESCUINAPA 100 ANGOSTURA 13 EL FUERTE 295 EL FUERTE 72 ESCUINAPA 13 SALVADOR ALVARADO 276 ANGOSTURA 63 SINALOA 4 CHOIX 178 ROSARIO 55 MOCORITO 3 ELOTA 151 BADIRAGUATO 38 ROSARIO 2 COSALÁ 109 MOCORITO 25 CONCORDIA 2 BADIRAGUATO 92 CHOIX 21 BADIRAGUATO 2 MOCORITO 72 COSALÁ 21 ELOTA 1 ANGOSTURA 70 ELOTA 13 SAN IGNACIO 0 SAN IGNACIO 51 CONCORDIA 13 CHOIX 0 CONCORDIA 43 SAN IGNACIO 5 COSALÁ 0 ESCUINAPA *DETALLE DE NUEVAS MUERTES REGISTRADAS HOY EN PLATAFORMA DE 54 a 86* *NAVOLATO* Masculino de 67 años muerto el 1 de febrero en HCivil (diabético) *ELOTA* Femenino de 76 años muerto el 3 de febrero en ISSSTE Mazatlán (hipertenso) *AHOME* 1. -

Descriptivo De La Distritación 2015

A SONORA CHOIX 007 DTTO CHIHUAHUA 14 DISTRITO 01 DTTO 17 DISTRITO DTTO 15 16 EL FUERTE 010 AHOME 001 DISTRITO 03 SINALOA 017 DISTRITO 06 DTTO 02 DTTO DISTRITO 0 5 C 04 BADIRAGUATO 003 DISTRITO 07 SALVADOR ALVARADO 015 DISTRITO 08 MOCORITO 013 GUASAVE 011 DISTRITO 10 DISTRITO 09 C ANGOSTURA 002 DISTRITO 13 DISTRITO CULIACAN 006 12 NAVOLATO 018 DTTO DTTO 1 4 DTTO 17 DI STRI TO DTTO 1 5 1 6 05 DISTRITO 11 A DISTRITO 18 DURANGO COSALA 005 DISTRITO 19 SAN IGNACIO 016 O C E A N O P A C I F I C O ELOTA 008 B DISTRITO 20 MAZATLAN 012 DISTRITO 23 B CONCORDIA 004 DI STRI TO 2 1 DTTO REGISTRO FEDERAL DE ELECTORES 2 2 COORDINACIÓN DE OPERACIÓN EN CAMPO INSTITUTO NACIONAL ELECTORAL DIRECCIÓN DE CARTOGRAFÍA ELECTORAL DISTRITO 21 ESCENARIO DISTRITOS LOCALES ROSARIO 014 SINALOA DISTRITO 24 S I M B O L O G Í A DTTO LÍMITES CLAVES GEOELECTORALES 22 INTERNACIONAL DISTRITO LOCAL 01 ESTATAL MUNICIPIO / DELEGACION 001 ESCUINAPA 009 DISTRITO LOCAL MUNICIPIO / DELEGACION ESCALA: 1: 500,000 INFORMACIÓN BÁSICA DISTRITOS MUNICIPIOS SECCIONES 0 5 10 20 30 40 24 18 3,804 KILÓM ETR OS PROYECCIÓN: UNIVERSAL TRANSVERSA DE MERCATOR; DATUM: WGS 84 FUENTE: R.F.E.,D.C.E. NAYARIT DESCRIPTIVO DE LA DISTRITACIÓN 2015 SINALOA El estado se integra con 24 Demarcaciones Distritales Electorales Locales, conforme a la siguiente descripción: Distrito 01 Esta Demarcación Territorial Distrital tiene su Cabecera ubicada en la localidad EL FUERTE perteneciente al municipio EL FUERTE, asimismo, se integra por un total de 2 municipios, que son los siguientes: • CHOIX, integrado por 71 secciones: de la 1726 a la 1737 y de la 1740 a la 1798. -

R00375316.Pdf

SECRETARIA DE ADMINISTRACION Y FINANZAS UNIDAD DE INVERSIONES OBRAS TERMINADAS PROYECTOS DE INVERSION EN INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPAMIENTO INVERSIÓN INVERSIÓN FECHA DE MUNICIPIO CONCEPTO DE OBRA LOCALIZACIÓN AUTORIZADA FECHA DE TÉRMINO CONVENIO CONVENIO EJERCIDA ($) INICIO ($) SECRETARIA DE DESARROLLO URBANO Y OBRAS 2,112,561,712 2,014,060,723.44 PUBLICAS LOS MOCHIS 11,387,282.50 10,997,019.51 REVESTIMIENTO DEL DREN JUAREZ ENTRE BLVD. JIQUILPAN Y AHOME 03-sep-12 14-dic-12 BLVD. PÓSEIDON DESVIO DE AGUAS PLUVIALES DEL DREN JUÁREZ HACIA EL 59,000,000.00 59,000,000.00 25,574,890.60 169 Días AHOME DREN BUENAVENTURA PARA PROTEGER CONTRA LAS LOS MOCHIS 14-oct-13 27-dic-14 y (prorroga inicio) INUNDACIONES 170 días LOS MOCHIS 40,000,000.00 39,995,328.13 1,982,994.81 AHOME LOS MOCHIS - AHOME 12-sep-11 29-ene-12 y 48 Días LOS MOCHIS 4,400,000.00 4,400,000.00 PAVIMENTACION CARRETERA LOS MOCHIS-AHOME , ENTRE AHOME 20-ago-12 22-may-13 160 Días EJIDO MEXICO Y CARRETERA A COMPUERTAS LOS MOCHIS 230,000,000.00 229,999,999.75 16,401,595.43 AHOME CENTRO DE USOS MULTIPLES 19-mar-13 30-jun-14 y 395 Días LOS MOCHIS 2,500,000.00 2,499,465.19 331,331.36 CONSTRUCCION DE ALMACENES ESPECIALIZADOS PARA 87 Días AHOME 13-abr-12 05-dic-12 y VACUNAS (EQUIPADOS CON CUARTO FRIO) (prorrofa inicio) 52 días LA PRIMAVERA 6,009,608.04 6,009,608.04 ANGOSTURA ANGOSTURA - LA PRIMAVERA 1.95KM 26-ene-12 30-abr-12 221,441.48 ANGOSTURA 1,940,000.00 1,725,193.03 ANGOSTURA CALLE 100 09-sep-11 07-dic-11 ALHUEY 2,860,000.00 2,654,706.91 ANGOSTURA GUAMUCHIL - ANGOSTURA (PASO POR ALHUEY) 09-sep-11 07-dic-11 LA ESPERANZA 3,060,000.00 3,054,000.62 53,636.31 ANGOSTURA ANGOSTURA - LA ESPERANZA 08-sep-11 02-mar-12 85 Días (prorrofa inicio) ANGOSTURA 326,302.40 326,302.40 PAVIMENTAR CALLE ELIAS MASCAREÑO , ENTRE HEBERTO ANGOSTURA 11-jun-12 31-jul-12 SINAGAWA Y CALLE DECIMA ANGOSTURA 501,732.80 501,732.80 PAVIMENTACION CALLE DECIMA, ENTRE CALLE LIBRADO RIVERA ANGOSTURA 04-jun-12 07-sep-12 Y 5 DE MAYO COL. -

Nombre De La Persona Física Beneficiada

Id Nombre de La Persona Física Beneficiada Primer Apellido de La Persona Física Beneficiada Segundo Apellido de La Persona Física Beneficiada Monto (en Pesos), Recurso, Beneficio O Apoyo (en D Unidad Territorial Edad (en su Caso) Sexo (en su Caso) 1 Jose Gael Carrillo Arredondo Aparatos Ortopedicos Sinaloa - Badiraguato - La Sabila 3 Masculino 2 Juana Ramos Zavala Silla De Ruedas Sinaloa - Culiacan - Culiacan 68 Masculino 3 Sebastiana Garcia Carreon Silla De Ruedas Sinaloa - Culiacan - Culiacan 90 Femenino 4 Adrian Gonzalez Sanchez Muleta Para Adulto Sinaloa - Culiacan - Culiacan 13 Masculino 5 Maria Hilda Mosqueda Ovalle Silla De Ruedas Sinaloa - Culiacan - Culiacan 72 Femenino 6 Tania Felix Salaiz Protesis Para Ojo Sinaloa - Salvador Alvarado - Guamuchil 18 Femenino 7 Consuelo Chaidez Jimenez Silla De Ruedas Sinaloa - Culiacan - Campo El Diez 77 Femenino 8 Juan Antonio Valdez Nevarez Baston Sencillo Sinaloa - Culiacan - Culiacan 54 Masculino 9 Nemesio Gambino Aispuro Silla De Ruedas Sinaloa - Sinaloa M - Culiacan 87 Masculino 10 Regina Gaxiola Jimenez Carreola Pci Sinaloa - Culiacan - Culiacan 6 Femenino 11 Juan Labra Sanchez Baston De 4 Apoyos Sinaloa - Culiacan - Argentina Ii 82 Masculino 12 Liboria Hernandez Castro Silla De Ruedas Sinaloa - Culiacan - Argentina Ii 73 Femenino 13 Kevin Yahir Mendez Cruz Aparatos Ortopedicos Sinaloa - Culiacan - Culiacan 2 Masculino 14 Ma. Carmen Alicia Guevara Torres Baston De 4 Apoyos Sinaloa - Culiacan - Culiacan 68 Femenino 15 Aurelia Soto Lopez Silla De Ruedas Sinaloa - Culiacan - Culiacan 80 Femenino -

Ley Orgánica Municipal Del Estado De Sinaloa

1 LEY ORGÁNICA MUNICIPAL DEL ESTADO DE SINALOA CAPÍTULO I DISPOSICIONES GENERALES ARTÍCULO 1o. El Municipio Libre es la base de la división territorial y de la organización política y administrativa del Estado de Sinaloa. ARTÍCULO 2o. Los Municipios que integran el Estado están investidos de personalidad jurídica propia, se administrarán por Ayuntamientos de elección popular directa, o por Consejos Municipales cuando así lo prevenga la presente Ley, y no habrá ninguna Autoridad intermedia entre ellos y los Poderes del Estado. ARTÍCULO 3o. Los Ayuntamientos administrarán libremente su hacienda, la cual se formará como lo previene el artículo 65. ARTÍCULO 4o. Los Ayuntamientos podrán celebrar convenios con el Estado a fin de integrar y armonizar sus actividades para el más eficaz cumplimiento de sus respectivas atribuciones. ARTÍCULO 5o. El Territorio del Estado se divide en dieciocho Municipios con las denominaciones siguientes: Choix, El Fuerte, Ahome, Guasave, Sinaloa, Mocorito, Angostura, Salvador Alvarado, Badiraguato, Culiacán, Navolato, Cosalá, Elota, San Ignacio, Mazatlán, Concordia, Rosario y Escuinapa, con la extensión y límites que actualmente les corresponden. ARTÍCULO 6o. Los Municipios se dividirán en Sindicaturas y éstas en Comisarías, cuya extensión y límites los determinarán los Ayuntamientos con la ratificación del Congreso del Estado. ARTÍCULO 7o. Los Centros Poblados de los Municipios tendrán las siguientes categorías: A). Ciudad, el que tenga más de veinticinco mil habitantes o sea Cabecera Municipal; B). Villa, el que tenga más de cinco mil habitantes o sea Cabecera de Sindicatura; C). Pueblo, el que tenga más de dos mil habitantes o sea Cabecera de Comisaría; y, D).Rancho, el que tenga hasta dos mil habitantes. -

ANEXO05 Dictamen-15-Días-TS.Pdf

LO O ><UJ «z DICTAMEN MEDIANTE EL CUAL SE ESTABLECE LA SANCiÓN QUE SE APLICARÁ A LA COALICiÓN TRANSFORMEMOS SINALOA, POR INFRINGIR LO DISPUESTO EN LOS ARTíCULOS 30, FRACCIONES 11Y XII, 32, 34, 117 BIS E, 117 BIS N Y 247 PÁRRAFO PRIMERO Y SEGUNDO, FRACCIONES I Y 11, DE LA LEY ELECTORAL DEL ESTADO DE SINALOA, EN RELACiÓN CON LOS ARTíCULOS 1, 3, FRACCIONES 11Y VI, DEL REGLAMENTO PARA REGULAR LA DIFUSiÓN Y FIJACiÓN DE LA PROPAGANDA DURANTE EL PROCESO ELECTORAL. --------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---Culiacán de Rosales, Sinaloa a 27 de Septiembre de 2013. ---------------------------- ---Vistas las constancias de los expedientes integrados por propaganda electoral y política de la Coalición "Transformemos Sinaloa", en los Distritos Electorales I de Choix, 11 de El Fuerte, 111 y IV de Ahome, V de Sinaloa, VI y VII de Guasave, VIII de Angostura, IX de Salvador Alvarado, X de Mocorito, XI Badiraguato, XIV de Culiacán, XV de Navolato, XVI Cosalá, XVIII de San Ignacio, XXI de Concordia, XXII de Rosario, XXIII de Escuinapa y XXIV de Culiacán, en el Estado de Sinaloa que infringe lo establecido en los artículos 30, fracción II y XII, 32, 34,117 Bis N, 117 Bis N y 247 de la Ley Electoral del Estado de Sinaloa, en relación con los artículos 1, 3 del Reglamento para Regular la Difusión y Fijación de la Propaganda durante el Proceso Electoral; y --------------------------------------------------------------------- -----------------------------------------RE S U L T A N D 0----------------------------------------- l. ANTECEDENTES. Renovación del CEE. --y ---1. Que mediante acuerdos número 65/2013 y 66/2013 publicados en eP Periódico Oficial "El Estado de Sinaloa" en fecha 2 de enero del año en curso, la LX Legislatura del Congreso del Estado de Sinaloa nombró al Presidente, Consejeros Ciudadanos Propietarios y Consejeros Ciudadanos Suplentes Generales, todos del Consejo Estatal Electoral del Estado de Sinaloa, quedando debidamente integrado dicho Consejo.---------------------------------------------------------- Convocatoria a elecciones.