American Choral Review Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serbian Orthodox Church in the USA Church Assembly—Sabor 800 Years of Autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church: “Endowed by God, Treasured by the People”

Serbian Orthodox Church in the USA Church Assembly—Sabor 800 Years of Autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church: “Endowed by God, Treasured by the People” August 1, 2019 Holy Despot Stephen the Tall and Venerable Eugenia (Lazarevich) LIBERTYVILLE STATEMENT OF THE PRESIDENTS OF THE CHURCH ASSEMBLY-SABOR REGARDING THE CONSTITUTION AND RELATED GOVERNING DOCUMENTS To the Very Reverend and Reverend Priests and Deacons, Venerable Monastics, the Members and Parishioners of the Church-School Congregations and Mission Parishes of the Serbian Orthodox Dioceses in the United States of America Beloved Clerics, Brothers and Sisters in Christ, As we have received numerous questions and concerns regarding the updated combined version of the current Constitution, General Rules and Regulations and Uniform Rules and Regulations for Parishes and Church School Congregations of the Serbian Orthodox Dioceses in the United States of America, that was published and distributed to all attendees and received by such on July 16, 2019 during the 22nd Church Assembly-Sabor, we deemed it necessary and appropriate to provide answers to our broader community regarding what was updated and why. The newly printed white bound edition is a compilation of all three prior documents, inclusive of past amendments and updated decisions rendered by previous Church Assemblies and the Holy Assembly of Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church. This was done in accordance with the May 7/24, 2018, HAB No. 45/MIN.171 decision of the Holy Assembly of Bishops of our Mother Church, the Serbian Orthodox Church, to whom we are and shall forever remain faithful. In terms of updates, there are two main categories: 1) the name change (i.e. -

Introduction

Introduction: By Malkhaz Erkvanidze Georgian Chant, the Gelati Monastery Chant School, Liturgical Chant for the Twelve Immovable Feasts and the Twelve Celebrations of Our Lord, [Ts’inasit’qvaoba: Kartuli Galoba, Gelatis skola, Tormet’ Sauplo da Udzrav Dghesasts’aulta Sagaloblebi, Meore T’omi, Tbilisi, 2006] Volume II, 2nd Edition, Tbilisi, 2006 This volume continues a series of Georgian chant publications intended to revitalize the medieval chant tradition. The first in the series was published in 2000 and includes the basic required chants for the All-Night Vigil and Divine Liturgy. This second collection contains the basic chants of the Twelve Great Feasts and the Immovable Feast Days, but unfortunately does not include the full breadth of chants from the Feast Days of other saints. The chants in both of these publications are in the Sada Kilo (‘Plain Mode’) and Namdvili Kilo (‘True-Simple Mode’),1 and originate from the medieval school of chant at the Gelati Monastery.2 In our opinion, the Sada Kilo chant from the Gelati and Martvili Monastery schools is the most suitable for church services, as it combines a masterful balance of text and melody. Georgian chant is believed to have originated in the Tao-Klarjeti region between the seventh and tenth centuries (present day NE Turkey)3 from where it spread to the major monastery-academies throughout Georgia. Chant flourished at the academy of Iqalto in far eastern Georgia, the Gelati academy in the Kutaisi region, and Martvili (Chqondidi) Monastery. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, chant was unified in the school of hymnography at the Gelati Monastery, which was among the leading spiritual and educational centers of the world at that time. -

The Beginnings of the Romanian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

Proceedings of SOCIOINT 2019- 6th International Conference on Education, Social Sciences and Humanities 24-26 June 2019- Istanbul, Turkey THE BEGINNINGS OF THE ROMANIAN AUTOCEPHALOUS ORTHODOX CHURCH Horia Dumitrescu Pr. Assist. Professor PhD., University of Piteşti, Faculty of Theology, Letters, History and Arts/ Centre for Applied Theological Studies, ROMANIA, [email protected] Abstract The acknowledgment of autocephaly represents a historical moment for the Romanian Orthodox Church, it means full freedom in organizing and administering internal affairs, without any interference or control of any church authority from outside. This church act did not remove the Romanian Orthodox Church from the unity of ecumenical Orthodoxy, but, on the contrary, was such as to preserve and ensure good relations with the Ecumenical Patriarchate and all other Sister Orthodox Churches, and promote a dogmatic, cult, canonical and work unity. The Orthodox Church in the Romanian territories, organized by the foundation of the Metropolis of Ungro-Wallachia (1359) and the Metropolis of Moldavia and Suceava (1401), became one of the fundamental institutions of the state, supporting the strengthening of the ruling power, to which it conferred spiritual legitimacy. The action of formal recognition of autocephaly culminated in the Ad Hoc Divan Assembly’s 1857 vote of desiderata calling for “recognition of the independence of the Eastern Orthodox Church, from the United Principalities, of any Diocesan Bishop, but maintaining unity of faith with the Ecumenical Church of the East with regard to the dogmas”. The efforts of the Romanian Orthodox Church for autocephaly were long and difficult, knowing a new stage after the Unification of the Principalities in 1859 and the unification of their state life (1862), which made it necessary to organize the National Church. -

Ensemble Basiani

Friday, October 21, 2016, 8pm Venue to be announced Ensemble Basiani George Donadze, artistic director Zurab Tskrialashvili, director Irakli Tkvatsiria Giorgi Khunashvili Tornike Merabishvili Zviad Michilashvili George Gabunia Lasha Metreveli Elizbar Khachidze Batu Lominadze Sergo Urushadze Zaza Zuriashvili PROGRAM Mravalzhamier (Long Life) – Table Song, Kakheti Orira – Travelling Song, Guria Tu ase turpa ikavi (You Were So Pretty) – Lyric-Love Song Circle Dance – Svaneti Shavi shashvi (The Black Thrush) – Hunters’ Song, Guria Tsmidao gmerto (O, Holy God) Saidumlo utskho da didebuli (A Mystery, Strange and Most Glorious) Tkveta ganmatavisuflebelo (As the Deliverer of the Captives) Motsikuli kristesagan gamorcheuli (Apostle Distinguished by Christ) Akebdit sakhelsa uplisasa (Praise Ye the Name of the Lord) Sashot mtiebisa (Out of the Womb) Imeruli naduri – Work Song, Imereti Tsintsqaro – Lyric-Love Song, Kakheti Gandagan – Dancing Song, Adjara Khasanbegura – Historical Ballad, Guria Veengara – Lullaby, Samegrelo Chakrulo – Table Song, Kakheti Chochkhatura – Work Song, Guria Tonight’s concert will last approximately 75 minutes and will be performed without an intermission. PROGRAM NOTES FOLK SONGS Why couldn’t I notice that you were so pretty, little violet? Mravalzhamier (Long Life) is a supra song from —Because your heart is closed for love. Kakheti (a region in eastern Georgia). The Now I met a new gardener who filled me with Geor gian supra (“table party”) usually begins cares and love. with Mravalzhamier, creating a fes tive mood. He talked to me sweetly and held me on his lap. As voices rise, so does the spirit of everyone at the table. The gathering becomes a celebration. Circle Dance is from Svaneti, a mountainous nurtsa ikharos mterma chvenzeda, region in northwest Georgia. -

TCHAIKOVSKY Liturgy of St

TCHAIKOVSKY Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom Nine Sacred Choruses Latvian Radio Choir Sigvards Kļava PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840–1893) Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, Op. 41 (1878) Liturgiya svyatogo Ioanna Zlatousta 1. After first Antiphon: Glory to the Father | Posle pervovo antifona: Slava Otsu i Sïnu 3:04 2 After the Little Entrance: Come, Let Us Worship | Posle malovo fhoda: Pridiite, poklonimsa 3:43 3. Cherubic Hymn | Heruvimskaya pesn: Izhe Heruvim 6:02 4. The Creed | Simvol verï 4:48 5. After the Creed: A Mercy of Peace | Posle Simvola verï: Milost mira 4:24 6. After the exclamation ‘Thine own of Thine…’: We Hymn to Thee |Posle vozglasheniya ”Tvoya ot Tvoih...”: Tebe poem 2:41 7. After the words ‘Especially for our most holy…’: Hymn to the Mother of God | Posle slov “Izriadno o presviatey...”: Dostoyno yest 3:26 8. The Lord’s Prayer: Our Father | Molitva Gospodnya: Otche nash 3:25 9. The Communion Hymn: Praise the Lord | Prichastnïy stih: Hvalite Gospoda 2:32 10. After the exclamation ‘In the fear of God…’: We have seen the True Light! | Posle vozglasheniya ”So strahom Bozhïim...”: Videhom svet istinï 3:26 Nine Sacred Choruses (1884–85) Devjati duhovno-muzykalnyh sotshinenij 11. Cherubic Hymn I | Heruvimskaya pesn I 6:05 12. Cherubic Hymn II | Heruvimskaya pesn II 5:51 13. Cherubic Hymn III | Heruvimskaya pesn III 6:01 14. We Hymn to Thee |Tebe poem 3:20 15. Hymn to the Mother of God | Dostoyno yest 3:03 16. Our Father | Otche nash 3:16 17. Blessed are They | Blazheni, yazhe ibral 3:23 18. -

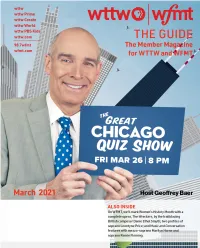

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

Among the Religious Functions Social Is One of the Most Important One

Demuri Jalaghonia , (Georgia) PhD, Professor at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Faculty of Humanities; Head of the Academic-Research Institute of Philosophy; Head of the Chair for Political Philosophy. GEORGIAN THEOLOGISTS ON THE INTITUTION OF MARRIAGE Among the religious functions social is one of the most important one. Religion actually influences the society, persons’ consolidations and individuals by means of belief, religious feelings and cult activities. Confessions, of course differ from each-other according to their aims and the means of implementation though each of them accomplish their specific social destination functions. Emil Durkheim points out that religion depicts not only the society structure but it supports to make it stable, religion has a uniting function as it concentrates men’s attention and inspires them with hope1. In traditional minor cultures, Durkheim proves, all the sides of life are precisely described by the religion. On the one part religious habits create new ideas and thinking categories, on the other part make the already established valuables steady. Religion is not only consecutive feelings and activities but it actually defines the rule of thinking of a man in traditional cultures2. As Michel Mill points out in spite of in what way the religious dimension will be displayed in social life we must always remember that the decrease of the religion political role do not at all mean an eradication of religious personal belief or social functions. Religious belief does not recently define functioning rules of states though it plays a vast role not only in personal but also in social lives. Very often theories of secularization meticulously define the place of religion in the present society and identify the weakening of traditional institution with the end of religion3. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS About Seraphic Fire . 4 About Patrick Dupré Quigley . .. 5 About Elena Sharkova . 6 Program . 7 Text & Translations . 8 Artists . 15 Artist Biographies . 16 Administration . 24 Our Supporters . 27 Two-Time GRAMMY® Nominee Oct 2017 Nov 2017 Dec 2017 Jan 2018 Feb 2018 Mar 2018 "After celebrating 15 years, this next season provides an eclectic musical journey through masterworks of cultural significance like Brahms’ timeless Liebeslieder Waltzes, as well as through high-quality under-performed music like David Lang's The Little Match Girl Passion. Our 16th Season continues to put South Florida at the center of artistic innovation with the country’s finest vocal artists performing history’s awe-inspiring repertoire." Apr 2018 May 2018 Patrick Dupré Quigley, Founder & Artistic Director Subscriptions Now on Sale! Subscribe at SeraphicFire.org or 305.285.9060 ABOUT SERAPHIC FIRE ABOUT PATRICK DUPRÉ QUIGLEY Led by Founder and Artistic Director Patrick Dupré appearance by conductor Elena Sharkova . The Quigley, Seraphic Fire brings top ensemble singers season also features collaborations with organist and instrumentalists from around the country to Nathan Laube and violinist Matthew Albert . perform repertoire ranging from Gregorian chant and Baroque masterpieces, to Mahler and newly Recognized as “one of the best excuses for commissioned works by this country’s leading living in Miami” (el Nuevo Herald) because of its composers . Two of the ensemble’s recordings, “vivid, sensitive performances” (The Washington Brahms: Ein Deutsches -

Resolutionsofthe2020diocesan

IN THE NAME OF THE HOLY AND LIFEGIVING TRINITY! We, the clergy, monastics, and representatives of the people of God, ordained and elected members to the Annual Assembly of the Serbian Orthodox Diocese of Eastern America, of the Serbian Orthodox Church, have gathered together at the Church of Saint Sava of Serbia in the God-protected City of Saint Petersburg, Florida on February 27 and 28, in the Year of Our Lord 2020. Today, as we celebrate the memory of Saint Onesimus, Apostle of the Seventy, and Venerable Paphnutius the Recluse of the Kiev Caves, the Holy Spirit has gathered us in the community of the Body of Christ that He might bring us closer to our Heavenly Father. Having announced the fullness of God’s Church, gathered around our Bishop, Father and Archpastor Irinej, we greet the fullness of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the person of His Holiness, the Archbishop of Pec, Metropolitan of Belgrade-Karlovac, and Serbian Patriarch Irinej and his Delegation. We also greet the members of the Episcopal Council of the Serbian Orthodox Church in North, Central and South America, as well as the members of the Central Church Council of the Serbian Orthodox Dioceses in the United States of America, Canada, and Central and South America. From this place we greet His Royal Highness, Crown Prince Alexander, Heir to the Throne, and his wife, Her Royal Highness Princess Katherine. We express our steadfast support for His Grace our Bishop Irinej, the Diocesan Council and the Diocesan Executive Board of the Serbian Orthodox Diocese of Eastern America, as well as the leadership of our Holy Church in our Serbian Fatherland, in the Region, and in the Diaspora, and to all persons of good will. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

3 Historical and Political Geography

World Regional Geography Book Series Series Editor E.F.J. de Mulder Haarlem, The Netherlands What does Finland mean to a Fin, Sichuan to a Shichuanian, and California to a Californian? How are physical and human geographical factors reflected in their present-day inhabitants? And how are these factors interrelated? How does history, culture, socio-economy, language and demography impact and characterize and identify an average person in such regions today? How does that determine her or his well-being, behaviour, ambitions and perspectives for the future? These are the type of questions that are central to The World Regional Geography Book Series, where physically and socially coherent regions are being characterized by their roots and future perspectives described through a wide variety of scientific disciplines. The Book Series presents a dynamic overall and in-depth picture of specific regions and their people. In times of globalization renewed interest emerges for the region as an entity, its people, its land- scapes and their roots. Books in this Series will also provide insight in how people from dif- ferent regions in the world will anticipate on and adapt to global challenges as climate change and to supra-regional mitigation measures. This, in turn, will contribute to the ambitions of the International Year of Global Understanding to link the local with the global, to be proclaimed by the United Nations as a UN-Year for 2016, as initiated by the International Geographical Union. Submissions to the Book Series are also invited on the theme ‘The Geography of…’, with a relevant subtitle of the authors/editors choice. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Since its launch in 1982, the Marco Polo label has for over twenty years sought to draw attention to unexplored repertoire.␣ Its main goals have been to record the best music of unknown composers and the rarely heard works of well-known composers.␣ At the same time it originally aspired, like Marco Polo himself, to bring something of the East to the West and of the West to the East. For many years Marco Polo was the only label dedicated to recording rare repertoire.␣ Most of its releases were world première recordings of works by Romantic, Late Romantic and Early Twentieth Century composers, and of light classical music. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again, particularly those whose careers were affected by political events and composers who refused to follow contemporary fashions.␣ Of particular interest are the operas by Richard Wagner’s son Siegfried, who ran the Bayreuth Festival for so many years, yet wrote music more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck. To Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich, Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan), and Bruder Lustig, which further explores the mysterious medieval world of German legend is now added Der Heidenkönig (The Heathen King).␣ Other German operas included in the catalogue are works by Franz Schreker and Hans Pfitzner. Earlier Romantic opera is represented by Weber’s Peter Schmoll, and by Silvana, the latter notable in that the heroine of the title remains dumb throughout most of the action.