Balance of Threat of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue Towards China's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Claim of Sovereignty Over Spratly and Paracel Islands: a Historical and Legal Perspective Teh-Kuang Chang

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 23 | Issue 3 1991 China's Claim of Sovereignty over Spratly and Paracel Islands: A Historical and Legal Perspective Teh-Kuang Chang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Teh-Kuang Chang, China's Claim of Sovereignty over Spratly and Paracel Islands: A Historical and Legal Perspective, 23 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 399 (1991) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol23/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. China's Claim of Sovereignty Over Spratly and Paracel Islands: A Historical and Legal Perspective Teh-Kuang Chang* I. INTRODUCTION (Dn August 13, 1990, in Singapore, Premier Li Peng of the People's Re- public of China (the PRC) reaffirmed China's sovereignty over Xisha and Nansha Islands.1 On December. 29, 1990, in Taipei, Foreign Minis- ter Frederick Chien stated that the Nansha Islands are territory of the Republic of China.2 Both statements indicated that China's claim to sov- ereignty over the Paracel and Spratly Islands was contrary to the claims of other nations. Since China's claim of Spratly and Paracel Islands is challenged by its neighboring countries, the ownership of the islands in the South China Sea is an unsettled international dispute.3 An understanding of both * Professor of Political Science, Ball State University. -

Defining EEZ Claims from Islands: a Potential South China Sea Change

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2014 Defining EEZ claims from islands: A potential South China Sea change Robert Beckman National University of Singapore, [email protected] Clive Schofield University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Beckman, Robert and Schofield, Clive, "Defining EEZ claims from islands: A potential South China Sea change" (2014). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 1409. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/1409 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Defining EEZ claims from islands: A potential South China Sea change Abstract In the face of seemingly intractable territorial and maritime disputes in the South China Sea, the article examines how the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC), sets out what maritime claims States can make in the South China Sea and how it establishes a framework that will enable States to either negotiate maritime boundary agreements or negotiate joint development arrangements (JDAs) in areas of overlapping maritime claims. It provides an avenue whereby the maritime claims of the claimants can be brought into line with international law, potentially allowing for meaningful discussions on cooperation and maritime joint development based on areas of overlapping maritime claims defined on the basis of the LOSC. -

Spratly Islands

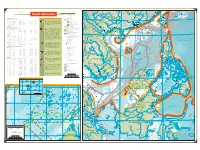

R i 120 110 u T4-Y5 o Ganzhou Fuqing n h Chenzhou g Haitan S T2- J o Dao Daojiang g T3 S i a n Putian a i a n X g i Chi-lung- Chuxiong g n J 21 T6 D Kunming a i Xingyi Chang’an o Licheng Xiuyu Sha Lung shih O J a T n Guilin T O N pa Longyan T7 Keelung n Qinglanshan H Na N Lecheng T8 T1 - S A an A p Quanzhou 22 T'ao-yüan Taipei M an T22 I L Ji S H Zhongshu a * h South China Sea ng Hechi Lo-tung Yonaguni- I MIYAKO-RETTO S K Hsin-chu- m c Yuxi Shaoguan i jima S A T21 a I n shih Suao l ) Zhangzhou Xiamen c e T20 n r g e Liuzhou Babu s a n U T Taichung e a Quemoy p i Meizhou n i Y o J YAEYAMA-RETTO a h J t n J i Taiwan C L Yingcheng K China a a Sui'an ( o i 23 n g u H U h g n g Fuxing T'ai- a s e i n Strait Claimed Straight Baselines Kaiyuan H ia Hua-lien Y - Claims in the Paracel and Spratly Islands Bose J Mai-Liao chung-shih i Q J R i Maritime Lines u i g T9 Y h e n e o s ia o Dongshan CHINA u g B D s Tropic of Cancer J Hon n Qingyuan Tropic of Cancer Established maritime boundary ian J Chaozhou Makung n Declaration of the People’s Republic of China on the Baseline of the Territorial Sea, May 15, 1996 g i Pingnan Heyuan PESCADORES Taiwan a Xicheng an Wuzhou 21 25° 25.8' 00" N 119° 56.3' 00" E 31 21° 27.7' 00" N 112° 21.5' 00" E 41 18° 14.6' 00" N 109° 07.6' 00" E While Bandar Seri Begawan has not articulated claims to reefs in the South g Jieyang Chaozhou 24 T19 N BRUNEI Claim line Kaihua T10- Hsi-yü-p’ing Chia-i 22 24° 58.6' 00" N 119° 28.7' 00" E 32 19° 58.5' 00" N 111° 16.4' 00" E 42 18° 19.3' 00" N 108° 57.1' 00" E China Sea (SCS), since 1985 the Sultanate has claimed a continental shelf Xinjing Guiping Xu Shantou T11 Yü Luxu n Jiang T12 23 24° 09.7' 00" N 118° 14.2' 00" E 33 19° 53.0' 00" N 111° 12.8' 00" E 43 18° 30.2' 00" N 108° 41.3' 00" E X Puning T13 that extends beyond these features to a hypothetical median with Vietnam. -

South China Sea Disputes: China Has Evidence of Historical Claims

www.rsis.edu.sg No. 165 – 15 August 2014 RSIS Commentary is a platform to provide timely and, where appropriate, policy-relevant commentary and analysis of topical issues and contemporary developments. The views of the authors are their own and do not represent the official position of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU. These commentaries may be reproduced electronically or in print with prior permission from RSIS and due recognition to the author(s) and RSIS. Please email: [email protected] for feedback to the Editor RSIS Commentaries, Mr Yang Razali Kassim. South China Sea Disputes: China Has Evidence of Historical Claims By Li Dexia & Tan Keng Tat Synopsis China possesses historical references dating back to the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127AD). They cannot be fairly presented in a two-page commentary. Commentary BILL HAYTON, in his RSIS Commentary entitled The Paracels: Historical Evidence Must Be Examined,’ asserted that "Advocates of the Chinese territorial claim to the islands of the South China Sea frequently cite vague historical references in support of their arguments". This assertion in the 3 July 2014 article has no merit. China’s territorial claim is based on centuries of verifiable historical records, long-term use, treaties, international/customary laws plus records from the prodigious sea voyages of the Yuan and Ming dynasties. China was the world's predominant maritime power between 1292 to 1433. Early Chinese references to Paracels To obliquely imply China was incapable of first discovery of islands in the South China Sea flies in the face of logic. To expect anyone to present the litany of verifiable evidence, dating from the Northern Song dynasty would require a monograph, not a two-page commentary. -

International Law Rules and Historical Evidences Supporting China's Title to the South China Sea Islands Jianming Shen

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review Volume 21 Article 1 Number 1 Fall 1997 1-1-1997 International Law Rules and Historical Evidences Supporting China's Title to the South China Sea Islands Jianming Shen Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_international_comparative_law_review Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Jianming Shen, International Law Rules and Historical Evidences Supporting China's Title to the South China Sea Islands, 21 Hastings Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 1 (1997). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol21/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. International Law Rules and Historical Evidences Supporting China's Title to the South China Sea Islands By JIANMING SHEN, S.J.D. * Table of Contents I. Introduction .........................................................................................2 Il. Rules of Title Applicable to Barely Inhabitable Territories ................. 7 A. General Modes of Territorial Acquisition .................................... 7 B. Criteria for Sovereignty over Uninhabitable Islands ......................... 10 III. China's Historic Title to the Xisha and Nansha Islands ...................... 15 A. Discovery and Expeditions Prior to the Han Dynasty .................. 15 B. Chinese Activities between the Han and Song Dynasties ............ 17 C. The Qian Li Changsha and Wanli Shitang of the Song Dynasty ...... 21 D. Chinese Activities in the Yuan Dynasty .................................... 27 E. Chinese Activities During the Ming and Qing Dynasties ........... -

What's Wrong with the Status Quo in the South China Sea?

What’s wrong with the status quo in the South China Sea? Bill Hayton Author – South China Sea: the struggle for power in Asia Associate Fellow, Chatham House @bill_hayton WHAT IS THE STATUS QUO? PRC occupies all Paracels plus 7 features in Spratlys. Taiwan occupies Itu Aba Vietnam occupies 21 features in Spratlys plus 6 underwater banks Philippines occupies 9/10 features in Spratlys; Malaysia occupies 5 reefs WHAT WOULD PEACE LOOK LIKE? • Does China intend to occupy every single feature within the U-shaped line? • Or does China accept that any agreement will have to involve compromise on territorial claims? • Does China agree that UNCLOS sets the rules for resource allocation and maritime rules everywhere? • Are the claimants prepared to accept the use of critical historical evidence in resolving the disputes? WHERE DO THREATS COME FROM? 1. Claimant states that refuse to accept compromise on territorial claims 2. Claimant states that deny the role of UNCLOS in the South China Sea 3. Specifically, claims to ‘historic rights’ are a clear threat to peace VIETNAM’S TROUBLES… Repsol drilled appraisal well in Block 136-03 in June 2017 General Fan Changlong visited Madrid and Hanoi to order the drilling to stop General Fan threatened attacks on Vietnamese positions on Vanguard Bank INDONESIA’S TROUBLES… Atlas found aboard Chinese fishing boat Gui Bei Yu in May 2016 Published by a state-owned publishing house Blatant violation of UNCLOS – yet standard issue for Chinese fishing boats MALAYSIA’S TROUBLES Chinese vessels on station at Luconia Shoals -

Vietnam's Different Negotiations with China Over Two Islands Dispute: Paracel and Spratly

VIETNAM'S DIFFERENT NEGOTIATIONS WITH CHINA OVER TWO ISLANDS DISPUTE: PARACEL AND SPRATLY BY MISS LUONG ANH LINH A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (ASIA PACIFIC STUDIES) THAMMASAT INSTITUTE OF AREA STUDIES THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC YEAR 2018 COPY RIGHT OF THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY Ref. code: 25616066090124ABM VIETNAM'S DIFFERENT NEGOTIATIONS WITH CHINA OVER TWO ISLANDS DISPUTE: PARACEL AND SPRATLY BY MISS LUONG ANH LINH A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (ASIA PACIFIC STUDIES) THAMMASAT INSTITUTE OF AREA STUDIES THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC YEAR 2018 COPY RIGHT OF THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY Ref. code: 25616066090124ABM THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY THAMMASAT INSTITUTE OF AREA STUDIES THESIS BY MISS LUONG ANH LINH ENTITLED VIETNAM'S DIFFERENT NEGOTIATIONS WITH CHINA OVER TWO ISLANDS DISPUTE: PARACEL AND SPRATLY was approved as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Asia Pacific Studies) on ................................................. Chairman (Lecturer Lasse Schuldt, Ph.D.) Member and Advisor (Lecturer Takashi Tsukamoto, Ph.D.) Member (Professor Robin Ramcharan, Ph.D.) Director (Associate Professor Suphat Suphachalasai, Ph.D.) Ref. code: 25616066090124ABM (1) Thesis Title VIETNAM'S DIFFERENT NEGOTIATIONS WITH CHINA OVER TWO ISLANDS DISPUTE: PARACEL AND SPRATLY Author Miss Luong Anh Linh Degree Master of Arts (Asia Pacific Studies) Major Field/Faculty/University Master of Arts (Asia Pacific Studies) Thammasat Institute of Area Studies Thammasat University Thesis Advisor Takashi Tsukamoto, Ph.D. Academic Year 2018 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to examine Vietnam‖s both bilateral and multilateral negotiations with China over Paracel and Spratly Islands, and to analyze why the dispute has yet to be negotiated via DOC (Declaration of Conduct) and Code of Conduct (COC). -

Chelonia Mydas) Nests Were Geolocated Xuande Islands (Amphitrite Group) in the Northeast (Fig

Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 2019, 18(1): 000–000 Guangdong Province, historically the largest known doi:10.2744/CCB-1307.1 nesting ground in China, has been monitored by local Ó 2019 Chelonian Research Foundation officers for more than a decade. However, the estimated number of nests has seen a dramatic decline from 53 mean Nest Productivity for Green Turtles (Chelonia nests/yr (range, 19À83) in the 1980s, to 25 nests/yr (range, mydas) at Qilianyu of Xuande Islands, South 1À61) in the 1990s, to fewer than 20 (range, 0À53) in the China Sea, P.R. China: Preliminary Findings 2000s and fewer than 5 nests/yr (range, 0À10) in the 2010s, mainly because of past overharvesting for nesting 1 2 3 YUYAN JIA ,JING WANG ,GEORGE H. BALAZS , females and eggs, coastal development, and pollution 1,* (Chan et al. 2007; Wang and Li 2008). In Lamma Island of AND MIN LIU Hong Kong, the estimated annual number of nests ranged 1State Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Science, College of from 8 to 0 from the 1990s, as reported by government Ocean and Earth Sciences, Xiamen University, Xiamen City, Fujian officers (Chan et al. 2007; Ng et al. 2014). In Taiwan, the Province, P.R. China total number of annual nests are no more than 20 spread [[email protected]; [email protected]]; among the different islands (including Lanyu Island, 2 Conservation International Foundation—China Program, Beijing, Penghu Islands, and Xiaoliuqiu Island) (Chen and Cheng P.R. China [[email protected]]; 1995; Cheng et al. 2008, 2009; Lo et al. -

The Modern Origins of China's South China Sea Claims

MCXXXX10.1177/0097700418771678Modern ChinaHayton 771678research-article2018 Article Modern China 1 –44 The Modern Origins of © The Author(s) 2018 Reprints and permissions: China’s South China sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700418771678DOI: 10.1177/0097700418771678 Sea Claims: Maps, journals.sagepub.com/home/mcx Misunderstandings, and the Maritime Geobody Bill Hayton1 Abstract This article offers a new account of the development of China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea. It argues that a collective Chinese belief in a “historic claim” to the reefs and rocks therein emerged in distinct episodes during the first half of the twentieth century, partly in response to perceived threats to the country’s sovereignty but mainly as attempts to shore up declining nationalist legitimacy. It situates the claim within efforts by Chinese intellectual and state elites to construct a national “geobody” in the first decades of the twentieth century. It argues that this was not a process of documenting a preexisting claim but of imagining and asserting one through the mobilization of both emotion and archival documents. Moreover, this account emphasizes the importance of the acquisition of knowledge from foreign sources and the confusion that entailed. The legacy of this confused claim-making shapes South China Sea geopolitics today. Keywords Paracel, Pratas, Spratly, sovereignty, territory, geography, U-shaped line, 9- dash line 1Asia-Pacific Programme, Chatham House, London, UK Corresponding Author: Bill Hayton, Asia-Pacific Programme, Chatham House, 10 St James’s Square, London, SW1Y 4LE, UK. Email: [email protected] 2 Modern China 00(0) The origins of China’s claims in the South China Sea have been remarkably understudied given the amount of political attention those claims currently attract. -

Marriage of Blogs and News: Opposites Attract?

Marriage of blogs and news: Opposites attract? An exploration of content similarity政 between治 the blogs and traditional news of major international media organizations大 立 學 國 ‧ ‧ N a y t t i i s o r n a e l i v C n hengchi U Ralph Jennings June 2013 1 MASS MEDIA, BLOGS 治 政 大 立 學 國 ‧ ‧ N a y t t i i s o r n e a i v l C n hengchi U 2 MASS MEDIA, BLOGS Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction What’s next if the media blend news with blogs………………………………..4 Literature review….………………….….…………………………………………5 History of blogs…………………………………………………………….....5 News gathering and news writing.....................................................................7 Reader involvement in news stories…………………….……………….………9 Media-technology convergence政 history………………………………治 .……..10 Blogs and mass media...……………………………………………大 .……….13 立 Media coverage: South China Sea issue of 2012...…………………………學 .16 Research questions國 ….……………………………………………………….20 Methodology....…………………..…….………………………………‧ .………...21 ‧ Grounded theoryN approach…………………………………………………..21 a y t Content sources…t ..…………………………………………………………i .22 io s Short e-mail interviewsn with journalists……………………………………r ..26 a e l i v Results…….…………………… C.………………………………………n .………..27 hengchi U Content survey….…….……...…………………………………….………….27 Fact and opinion………………………………………………………. 28 Writing styles……………………………………………………………………30 Type, purpose of story………………………………………………………….32 Summary of content trends……………………………………………...36 Analysis of interviews with journalists--..……………………....…………….38 Gatekeeping by editors………………………………………………….38 -

Calculating China's Advances in the South China Sea

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1998-03-01 Dragon in the shadows: calculating China's advances in the South China Sea Studeman, Michael William Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/8276 WOXUBF 01 SCHOOL VAL rGRA TE 01 MOr CA - NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS DRAGON IN THE SHADOWS: CALCULATING CHINA'S ADVANCES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA by Michael William Studeman March, 1998 Thesis Advisor: Solomon Karmel Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited, REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED March 1998 Master's Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE d DRAGON IN THE SHADOWS: 5. FUNDING NUMBERS CALCULATING CHINA'S ADVANCES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA 6. AUTHOR(S) MICHAEL WILLIAM STUDEMAN 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION Monterey CA 93943-5000 REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE UNIVERSITY of NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE ACADEMY SFRATLY8: M AREA of FUTURE GOJ^FL^GT ©R PEACE

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE ACADEMY SFRATLY8: m AREA OF FUTURE GOJ^FL^GT ©R PEACE ? BY ARUJUNAN NARAYANAN NOVEMBER 1989 A SUB-THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES I CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT. MAPS. ABBREVIATIONS. GLOSSARY. 1. INTRODUCTION. 2. THE SPRATLYS. 3. SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ISLANDS. (a) Strategic significance. (b) Economic significance. 4. THE CLAIMANTS, AND THE BASIS OF THEIR CLAIMS. (a) Peoples' Republic of China. (b) Republic of China. (c) Socialist Republic of Vietnam. (d) Philippines. (e) Malaysia. 5.ASSESSMENT0F EACH CLAIM. 6. FUTURE PROSPECTS. (a) Reemergence of the PRC as a maritime power in the South China Sea. (b) Possibility of maintaining the status quo. (c) Possibility of cooperation amongst the other contestants against the PRC (d) Super power intervention. (e) Emergence of Malay regionalism. (f) Reemergence of Japan as a military power. (g) Joint authority. (h) Negotiation & settlement II 7. CONCLUSION. BIBLIOGRAPHY. APPENDIX. 111 DEDICATED TO: MY FATHER NARAYANAN FOR TEACHING ME THE VALUE OF WORK. MY MOTHER VEERAMAH WHO TAUGHT ME TO LOVE HUMANITY. MY WIFE ANGAMAH FOR HER PATIENCE. IV Preface and acknowledgement. This sub-thesis is the result of assistance given by many good-hearted individuals. Without their help, it would not be possible for me to pursue the study and to complete the work within the given time. At the University College, Australian Defence Force Academy, I was fortunate to have Dr. Carlyle A. Thayer, to whom the credit, if any, should go. His encouragement, advice and guidance were of great help.