Astronomical Observations During Willem Barents's Third Voyage To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arctic Expedition12° 16° 20° 24° 28° 32° Spitsbergen U Svalbard Archipelago 80° 80°

distinguished travel for more than 35 years Voyage UNDER THE Midnight Sun Arctic Expedition12° 16° 20° 24° 28° 32° Spitsbergen u Svalbard Archipelago 80° 80° 80° Raudfjorden Nordaustlandet Woodfjorden Smeerenburg Monaco Glacier The Arctic’s 79° 79° 79° Kongsfjorden Svalbard King’s Glacier Archipelago Ny-Ålesund Spitsbergen Longyearbyen Canada 78° 78° 78° i Greenland tic C rcle rc Sea Camp Millar A U.S. North Pole Russia Bellsund Calypsobyen Svalbard Archipelago Norway Copenhagen Burgerbukta 77° 77° 77° Cruise Itinerary Denmark Air Routing Samarin Glacier Hornsund Barents Sea June 20 to 30, 2022 4° 8° Spitsbergen12° u Samarin16° Glacier20° u Calypsobyen24° 76° 28° 32° 36° 76° Voyage across the Arctic Circle on this unique 11-day Monaco Glacier u Smeerenburg u Ny-Ålesund itinerary featuring a seven-night cruise round trip Copenhagen 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada aboard the Five-Star Le Boréal. Visit during the most 2 Arrive in Copenhagen, Denmark enchanting season, when the region is bathed in the magical 3 Copenhagen/Fly to Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, light of the Midnight Sun. Cruise the shores of secluded Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago/Embark Le Boréal 4 Hornsund for Burgerbukta/Samarin Glacier Spitsbergen—the jewel of Norway’s rarely visited Svalbard 5 Bellsund for Calypsobyen/Camp Millar archipelago enjoy expert-led Zodiac excursions through 6 Cruising the Arctic Ice Pack sandstone mountain ranges, verdant tundra and awe-inspiring 7 MåkeØyane/Woodfjorden/Monaco Glacier ice formations. See glaciers calve in luminous blues and search 8 Raudfjorden for Smeerenburg for Arctic wildlife, including the “King of the Arctic,” the 9 Ny-Ålesund/Kongsfjorden for King’s Glacier polar bear, whales, walruses and Svalbard reindeer. -

Of Penguins and Polar Bears Shapero Rare Books 93

OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS Shapero Rare Books 93 OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS EXPLORATION AT THE ENDS OF THE EARTH 32 Saint George Street London W1S 2EA +44 20 7493 0876 [email protected] shapero.com CONTENTS Antarctica 03 The Arctic 43 2 Shapero Rare Books ANTARCTIca Shapero Rare Books 3 1. AMUNDSEN, ROALD. The South Pole. An account of “Amundsen’s legendary dash to the Pole, which he reached the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram”, 1910-1912. before Scott’s ill-fated expedition by over a month. His John Murray, London, 1912. success over Scott was due to his highly disciplined dogsled teams, more accomplished skiers, a shorter distance to the A CORNERSTONE OF ANTARCTIC EXPLORATION; THE ACCOUNT OF THE Pole, better clothing and equipment, well planned supply FIRST EXPEDITION TO REACH THE SOUTH POLE. depots on the way, fortunate weather, and a modicum of luck”(Books on Ice). A handsomely produced book containing ten full-page photographic images not found in the Norwegian original, First English edition. 2 volumes, 8vo., xxxv, [i], 392; x, 449pp., 3 folding maps, folding plan, 138 photographic illustrations on 103 plates, original maroon and all full-page images being reproduced to a higher cloth gilt, vignettes to upper covers, top edges gilt, others uncut, usual fading standard. to spine flags, an excellent fresh example. Taurus 71; Rosove 9.A1; Books on Ice 7.1. £3,750 [ref: 96754] 4 Shapero Rare Books 2. [BELGIAN ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION]. Grande 3. BELLINGSHAUSEN, FABIAN G. VON. The Voyage of Fete Venitienne au Parc de 6 a 11 heurs du soir en faveur de Captain Bellingshausen to the Antarctic Seas 1819-1821. -

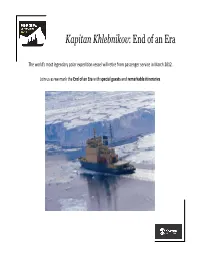

End of an Eraagent

Kapitan Khlebnikov: End of an Era The world’s most legendary polar expedition vessel will retire from passenger service in March 2012. Join us as we mark the End of an Era with special guests and remarkable itineraries. 2 Only 112 people will participate in any one of these historic voyages. As a former guest you can save 5% off the published price of these remarkable expeditions, and be one of the very few who will be able to say—I was on the Khlebnikov at the End of an Era. The legendary icebreaker Kapitan Khlebnikov will retire as an expedition vessel in March 2012, returning to escort duty for ships sailing the Northeast Passage. As Quark's flagship, the vessel has garnered more polar firsts than any other passenger ship. Under the command of Captain Petr Golikov, Khlebnikov circumnavigated the Antarctic continent, twice. The ship was the platform for the first tourism exploration of the Dry Valleys. The icebreaker has transited the Northwest Passage more than any other expedition ship. Adventurers aboard Khlebnikov were the first commercial travelers to witness a total eclipse of the sun from the isolation of the Davis Sea in Antarctica. In 2004, the special attributes of Kapitan Khlebnikov made it possible to visit an Emperor Penguin rookery in the Weddell Sea that had not been visited for 40 years. 3 End of an Era at a Glance Itineraries Start End Special Guests Northwest Passage: West to East July 18, 2010 August 5, 2010 Andrew Lambert, author of The Gates of Hell: Sir John Franklin’s Tragic Quest for the Northwest Passage. -

The Lore of the Stars, for Amateur Campfire Sages

obscure. Various claims have been made about Babylonian innovations and the similarity between the Greek zodiac and the stories, dating from the third millennium BCE, of Gilgamesh, a legendary Sumerian hero who encountered animals and characters similar to those of the zodiac. Some of the Babylonian constellations may have been popularized in the Greek world through the conquest of The Lore of the Stars, Alexander in the fourth century BCE. Alexander himself sent captured Babylonian texts back For Amateur Campfire Sages to Greece for his tutor Aristotle to interpret. Even earlier than this, Babylonian astronomy by Anders Hove would have been familiar to the Persians, who July 2002 occupied Greece several centuries before Alexander’s day. Although we may properly credit the Greeks with completing the Babylonian work, it is clear that the Babylonians did develop some of the symbols and constellations later adopted by the Greeks for their zodiac. Contrary to the story of the star-counter in Le Petit Prince, there aren’t unnumerable stars Cuneiform tablets using symbols similar to in the night sky, at least so far as we can see those used later for constellations may have with our own eyes. Only about a thousand are some relationship to astronomy, or they may visible. Almost all have names or Greek letter not. Far more tantalizing are the various designations as part of constellations that any- cuneiform tablets outlining astronomical one can learn to recognize. observations used by the Babylonians for Modern astronomers have divided the sky tracking the moon and developing a calendar. into 88 constellations, many of them fictitious— One of these is the MUL.APIN, which describes that is, they cover sky area, but contain no vis- the stars along the paths of the moon and ible stars. -

The Ortelius Incident in the Hinlopen Strait—A Case Study on How Satellite-Based AIS Can Support Search and Rescue Operations in Remote Waters

resources Case Report The Ortelius Incident in the Hinlopen Strait—A Case Study on How Satellite-Based AIS Can Support Search and Rescue Operations in Remote Waters Johnny Grøneng Aase 1,2 ID 1 Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 129, Hobart, TAS 7001, Australia; [email protected] 2 Department of Research and Development, Norwegian Defence Cyber Academy, P.O. Box 800, Postmottak, NO-2617 Lillehammer, Norway; [email protected]; Tel.: +47-9285-2550 Received: 26 April 2017; Accepted: 24 July 2017; Published: 27 July 2017 Abstract: In this paper, Automatic Identification System (AIS) data collected from space is used to demonstrate how the data can support search and rescue (SAR) operations in remote waters. The data was recorded by the Norwegian polar orbiting satellite AISSat-1. This is a case study discussing the Ortelius incident in Svalbard in early June 2016. The tourist vessel flying the flag of Cyprus experienced engine failure in a remote part of the Arctic Archipelago. The passengers and crew were not harmed. There were no Norwegian Coast Guard vessels in the vicinity. The Governor of Svalbard had to deploy her vessel Polarsyssel to assist the Ortelius. The paper shows that satellite-based AIS enables SAR coordination centers to swiftly determine the identity and precise location of vessels in the vicinity of the troubled ship. This knowledge makes it easier to coordinate SAR operations. Keywords: tourism; polar; search and rescue; SAR; Arctic; Svalbard; AISSat-1; Ortelius 1. Introduction On Friday 3 June 2016 at 12:30 am local time, the tourist vessel Ortelius reported engine trouble in the vicinity of the Vaigatt Islands in the Hinlopen Strait. -

Magnetic North: Artists and the Arctic Circle

Magnetic north Artists And the Arctic circle On view May 28, 2014 through August 29, 2014 Magnetic North is organized by The Arctic Circle in association with The Farm, Inc. The exhibition is sponsored by the 1285 Avenue of the Americas Art Gallery, in partnership with Jones Lang LaSalle, as a community based public service. IN MEMORY OF TERRY ADKINS (1953–2014) 2013 Arctic Circle Expedition Sarah Anne Johnson Circling the Arctic, 2011 Magnetic North How do people imagine the landscapes they find themselves in? How does the land shape the imaginations of people who dwell in it? How does desire itself, the desire to comprehend, shape knowledge? —Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams he Arctic Circle is a non-profit expeditionary residency program that brings together international groups of artists, writers, composers, architects, scientists, and educators. For Tseveral weeks each year, participants voyage into the open seas and fjords of the Svalbard archipelago aboard a specially equipped sailing vessel. The voyagers live and work together, aiding one another in the daily challenges of conducting research and creating new work based on their experiences. The residency is both a journey of discovery and a laboratory for the convergence of ideas and disciplines. Magnetic North comprises a selection of works by more than twenty visual and sound artists from the 2009–2012 expeditions. The exhibition encompasses a wide range of artistic practices, including photography, video, sound recordings, performance documentation, painting, sculpture, and kinetic and interactive installations. Taken together, the works of art offer unique and diverse perspectives on a part of the world rarely seen by others, conveying the desire to comprehend and interpret a largely uninhabitable and unknowable place. -

Kapitan Khlebnikov

kapitan khlebnikov Expeditions that Mark the End of an Era 1991-2012 01 End of an Era 22 Circumnavigation of the Arctic 03 End of an Era at a Glance 24 Northeast Passage: Siberia and the Russian Arctic 04 Kapitan Khlebnikov 26 Greenland Semi-circunavigation: Special Guests 06 The Final Frontier 10 Northwest Passage: Arctic Passage: West to East 28 Amundsen’s Route to Asia 12 Tanquary Fjord: Western Ross Sea Centennial Voyage: Ellesmere Island 30 Farewell to the Emperors 14 Ellesmere Island and of Antarctica Greenland: The High Arctic 32 Antarctica’s Far East – 16 Emperor Penguins: The Farewell Voyage: Saluting Snow Hill Island Safari the 100th Anniversary of the Australasia Antarctic Expedition. 18 The Weddell Sea and South Georgia: Celebrating the 34 Dates and Rates Heroes of Endurance 35 Inclusions 20 Epic Antarctica via the Terms and Conditions of Sale Phantom Coast and 36 the Ross Sea Only 112 people will participate in any one of these historic voyages. end of an era Join us as we mark the End of an Era with special guests and remarkable itineraries. The legendary icebreaker Kapitan Khlebnikov will retire transited the Northwest Passage more than any other as an expedition vessel in March 2012, returning to expedition ship. Adventurers aboard Khlebnikov were the duty as an escort ship in the Russian Arctic. As Quark’s first commercial travelers to witness a total eclipse of the flagship, the vessel has garnered more polar firsts than sun from the isolation of the Davis Sea in Antarctica. In any other passenger ship. Under the command of Captain 2004, the special attributes of Kapitan Khlebnikov made it Petr Golikov, Khlebnikov circumnavigated the Antarctic possible to visit an Emperor Penguin rookery in the Weddell continent, twice. -

Arctic Saga: Exploring Spitsbergen Via the Faroes and Jan Mayen Three

SPITSBERGEN, THE FAROES & JAN MAYEN SPITSBERGEN, GREENLAND & ICELAND Exploring the Fair Isle coastline; an encounter with Svalbard Reindeer; capturing the scenery. A Zodiac cruise with a view. Arctic Ocean GREENLAND SVALBARD Longyearbyen Bellsund Longyearbyen Hornsund Greenland Sea Arctic Saga: Barents GREENLAND Sea Three Arctic Islands: SVALBARD Jan Mayen FROM Exploring Spitsbergen via OSLO Norwegian Sea Spitsbergen, Greenland and Iceland SOUTHBOUND the Faroes and Jan Mayen Scoresby Atlantic Ocean A Sund RCT TO IC C OSLO Departing from Aberdeen, Scotland, the Arctic Saga voyage visits four remote IRCL Named one of the 50 Tours of a Lifetime by National Geographic Traveler, E Milne Ittoqqortoormiit Arctic islands. Sail through the North Atlantic to Fair Isle, famous for its bird Faroe Islands NORWAY this voyage offers the best of the eastern Arctic in one voyage. You start in Land observatory, followed by two days exploring the Viking and Norse sites on Shetland Spitsbergen, Norway, then sail south to Greenland to explore the world’s Denmark Islands Strait the Faroe Islands. Then it’s onto the world’s northernmost volcanic island, Atlantic Ocean Oslo largest fjord system and end in Iceland. There’s something for everyone: CLE Orkney C CIR ARCTI Jan Mayen. The last two days of your 14-day voyage are spent exploring Islands Fair Isle polar bears, walrus, muskoxen, local culture, ancient Thule settlements, Aberdeen Spitsbergen, always on the lookout for polar bears. hikes along the glacial moraine and tundra, and more. Reykjavik ICELAND Nature is the tour guide: Sea, ice, and weather conditions will determine your trip itinerary. Embrace the unexpected. -

Hacquebord, Louwrens; Veluwenkamp, Jan Willem

University of Groningen Het topje van de ijsberg Boschman, Nienke; Hacquebord, Louwrens; Veluwenkamp, Jan Willem IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Boschman, N., Hacquebord, L., & Veluwenkamp, J. W. (editors) (2005). Het topje van de ijsberg: 35 jaar Arctisch centrum (1970-2005). (Volume 2 redactie) Barkhuis Publishing. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 04-10-2021 Twenty five years of multi-disciplinary research into the17th century whaling settlements in Spitsbergen L. -

Development and Achievements of Dutch Northern and Arctic Cartography

ARCTIC’ VOL. 37, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 1984) P. 493.514 Development and Achievements of Dutch Northern and Arctic Cartography. in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth :Centuries GUNTER. SCHILDER* ther north, as far as the Shetlands the Faroes, in line with INTRODUCTION and the expansion of the Dutch .fishing and trading areas. The During the sixteenth and .seventeenth. centuries, the Dutch Thresmr contains a number of coastal viewsfrom the voyage made. a vital contribution to. the mapphg of the northern and around the North Capeas far as ‘‘Wardhuys”. Although there arctic regions, and their caPtographic work piayed a decisive is no mapofthis region, there is.a map of the coasts of Karelia part in expanding. the ,geographical .knowledgeof that time. and Russia to the east of the White Sea asfar as the Pechora, Amsterdam became the centre.of international map production accompanied by a text with instructionsfor navigation as far as and the map trade. Its Cartographers and publishers acquired Vaygach and Novaya Zemlya (Waghenaer, 1592:fo101-105). their knowledge partly from the results of expeditions fitted A coastal view.of the latter is also given.s The fact that Wag- out by theirfellow countrymen and, partlyfrom foreign henaer had access to original sources is shown by the inclusion voyages of discovery. This paper will describe the growing- in the Thresoor of the only known accountof Olivier Brunel’s Dutch..awarenessof .the northern and arctic regions. stage by voyage to-NovayaZemlya in 1584 (Waghenaer, ‘1592:P104).6 stage and region by region, with the aid of Dutch. maps. Anotherimportant document is WillemBiuentsz’s map of northern Scandinavia, which extends as faras the entrance to THE PROGRESS OF DUTCH KNOWLEDGE IN THE NORTH .the White Sea, and shows.al1 the reefs and shallows(Fig. -

Scott Shapiro November 7, 2014 Attached Are the First Two Chapters

Scott Shapiro November 7, 2014 Attached are the first two chapters from a book manuscript that I am writing with my colleague Oona Hathaway, tentatively titled “THE WORST CRIME OF ALL: THE PARIS PEACE PACT AND THE BEGINNING OF THE END OF WAR.” This cover note is meant to help situate the chapters in the broader project. The first part describes what we call the Old World Order—a system that relied on war as the linchpin of law. The first two chapters center on Grotius and the legal order he helped establish. The subsequent chapters of this part show how war was a source of legal redress and legal rights. The legal rights to territory, people, and goods were decided by war—even ones that were entirely unjust. The second part of the book—comprised of four chapters—tells the story of what we argue is a deep shift in the legal meaning of war—the end of the Old World Order and the beginning of something fundamentally new. This shift, we argue, has consequences not just for states’ recourse to war, but for international law and the international system as a whole. The chapter that begins this second part of the book examines the “war to outlaw war”—the global movement to reject the remedial conception of war that characterized the Old World Order. That chapter ends with the signing of the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact (also called the Paris Peace Pact or Briand-Kellogg Pact). The next chapter examines the consequences that flowed from the decision to reject the legal rules that underpinned the Old World Order without first sorting out the legal rules and institutions that would take their place. -

T Avel Technology Rganisation

T avel Technology rganisation Ill Ill Medieval Europe Papers of the 'Medieval Europe Brugge 1997' Conference Volume 8 edited by Guy De Boe & Frans Verhaeghe LA.P. Rapporten 8 Zellik 1997 I.A.P. Rapporten uitgegeven door I edited by Prof Dr. Guy De Boe T avel echnology ganisation in Medieval Europe Papers of the 'Medieval Europe Brugge 1997' Conference Volume 8 edited by Guy De Boe & Frans Verhaeghe I.A.P. Rapporten 8 Zellik 1997 Een uitgave van het Published by the Instituut voor het Archeologisch Patrimonium Institute for the Archaeological Heritage W etenschappelijke instelling van de Scientific Institution of the Vlaamse Gemeenschap Flemish Community Departement Leefmilieu en Infrastructuur Department of the Environment and Infrastructure Administratie Ruimtelijke Ordening, Huisvesting Administration of Town Planning, Housing en Monumenten en Landschappen and Monuments and Landscapes Doomveld Industrie Asse 3 nr. 11, Bus 30 B -1731 Zellik- Asse Tel: (02) 463.13.33 (+ 32 2 463 13 33) Fax: (02) 463.19.51 (+ 32 2 463 19 51) DTP: Arpuco. Seer.: M. Lauwaert & S. Van de Voorde. ISSN 1372-0007 ISBN 90-75230-09-5 D/1997 /6024/8 08 TRAVEL, TECHNOLOGY AND 0RGANISATION - VERKEERSTECHNOLOGIE EN REIZEN TRANSPORTS ET VOYAGES - VERKEHRSTECHNOLOGIE UND REISEN was organized by Karel Vlierman werd georganiseerd door Hubert De Witte fut organisee par wurde veranstaltet von Preface The medieval world is often perceived as a fairly onwards but also of wrecks dating from Early Modem closed and static society where traffic and travelling times illustrate the point. The technological develop was fairly limited apart from such exceptions as the ments they reflect and which can often be identified Scandinavian regions in the Viking Age and the and documented only through archaeological evidence growing international trading systems which charac deserve attention not only because of their significance terize the development of the economic world parti for trade and exchange but also because they reveal cularly from the 12th century onwards.