The Bloomsbury Short Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the Short Story in English, 50 | Spring 2008 Beyond the Boundaries of Language: Music in Virginia Woolf’S “The String Quar

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 50 | Spring 2008 Special issue: Virginia Woolf Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quartet” Émilie Crapoulet Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/690 ISSN : 1969-6108 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Rennes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 juin 2008 ISSN : 0294-04442 Référence électronique Émilie Crapoulet, « Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quartet” », Journal of the Short Story in English [En ligne], 50 | Spring 2008, mis en ligne le 01 juin 2011, consulté le 03 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/690 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 3 décembre 2020. © All rights reserved Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quar... 1 Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quartet” Émilie Crapoulet “its [sic] music I want; to stimulate & suggest” (Woolf 1978a: 320) 1 From an author who felt that “the only thing in this world is music - music and books and one or two pictures” (1975: 41), and who, in her earliest years, humorously toyed with the idea of founding a colony “where there shall be no marrying - unless you happen to fall in love with a symphony of Beethoven” (1975: 41-42), it is hardly surprising that music was an art which directly inspired Virginia Woolf’s own literary compositions, playing a central role in her work as a writer. Woolf’s early technical proficiency,1 -

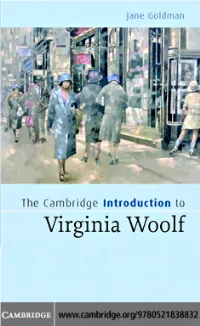

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf for Students of Modern Literature, the Works of Virginia Woolf Are Essential Reading

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf For students of modern literature, the works of Virginia Woolf are essential reading. In her novels, short stories, essays, polemical pamphlets and in her private letters she explored, questioned and refashioned everything about modern life: cinema, sexuality, shopping, education, feminism, politics and war. Her elegant and startlingly original sentences became a model of modernist prose. This is a clear and informative introduction to Woolf’s life, works, and cultural and critical contexts, explaining the importance of the Bloomsbury group in the development of her work. It covers the major works in detail, including To the Lighthouse, Mrs Dalloway, The Waves and the key short stories. As well as providing students with the essential information needed to study Woolf, Jane Goldman suggests further reading to allow students to find their way through the most important critical works. All students of Woolf will find this a useful and illuminating overview of the field. JANE GOLDMAN is Senior Lecturer in English and American Literature at the University of Dundee. Cambridge Introductions to Literature This series is designed to introduce students to key topics and authors. Accessible and lively, these introductions will also appeal to readers who want to broaden their understanding of the books and authors they enjoy. Ideal for students, teachers, and lecturers Concise, yet packed with essential information Key suggestions for further reading Titles in this series: Bulson The Cambridge Introduction to James Joyce Cooper The Cambridge Introduction to T. S. Eliot Dillon The Cambridge Introduction to Early English Theatre Goldman The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf Holdeman The Cambridge Introduction to W. -

Virginia Woolf & String Quartets Concert

Virginia Woolf & String Quartets Robinson College Chapel Cambridge 3 November 2016, 7.45pm Kreutzer Quartet Peter Sheppard Skærved – Violin Mihailo Trandafilovski – Violin Clifton Harrison – Viola Neil Heyde – Cello Kindly supported by PREFACE Welcome to the third concert of ‘Virginia Woolf & Music’. The project explores the role of music in Woolf’s life and afterlives: it includes new commissions, world premieres and little-known music by women composers. Outreach activities and educational resources have been central to the project since it began in 2015. Concerts on Woolf and Bloomsbury continue throughout 2016- 17. For further details see: http://virginiawoolfmusic.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk Woolf (1882-1941) was a knowledgeable, almost daily, listener to ‘classical’ music, fascinated by the cultural practice of music and by the relationships between music and writing. Towards the end of her life she famously remarked, ‘I always think of my books as music before I write them’. Her writing continues to inspire composers who have set her words or responded more obliquely to her work. This concert takes its cue from Woolf’s extraordinary experimental short fiction, ‘The String Quartet’ (1921). The work explores the pleasures and frustrations of ‘capturing’ music in language. Juxtaposing the banal remarks that frame the performance with the exuberant flights of fancy that unfold during the playing, Woolf’s work celebrates music’s capacity to stimulate memories and associations. And it celebrates too music’s own ‘weaving’ into a formal ‘pattern’ and ‘consummation’. On 7 March 1920, Woolf attended a concert that included a Schubert quintet ‘to take notes for my story’. -

Archetypal Figures in Mrs Dalloway

Modern Language Society ARCHETYPAL FIGURES IN "MRS DALLOWAY" Author(s): Jacqueline E. M. Latham Source: Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, Vol. 71, No. 3 (1970), pp. 480-488 Published by: Modern Language Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43342569 Accessed: 28-10-2019 13:19 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Modern Language Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Neuphilologische Mitteilungen This content downloaded from 143.107.3.152 on Mon, 28 Oct 2019 13:19:53 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 480 ARCHETYPAL FIGURES IN MRS D ALLOW AY Although Septimus Smith's recurring visions in Mrs Dalloway are clearly significant, no one has identified the elements of which they are composed. Two important image clusters frequently reappear; the first is centred on the figure of a man isolated and suffering: "His body was macerated until only the nerve fibres were left. It was spread like a veil upon a rock. He lay very high, on the back of the world."1 The second image has as its centre a drowned sailor and suggests that pain has given way to peace. -

Virginia Woolf's Short Fiction: a Study of Its Relation

VIRGINIA WOOLF'S SHORT FICTION: A STUDY OF ITS RELATION TO THE STORY GENRE; AND AN EXPLICATION OF THE KNOWN STORY CANON by David Roger Tallentire B.Sc, The University of British Columbia, 1963 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard. THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1968 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirement for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date /&, /?6S ii ABSTRACT The short stories of Virginia Woolf have never re• ceived serious scrutiny, critics determinedly maintaining that the novels contain the heart of the matter and that the sto• ries are merely preparatory exercises. Mrs. Woolf, however, provides sufficient evidence that she was "on the track of real discoveries" in the stories, an opinion supported by her Bloomsbury mentors Roger Fry and Lytton Strachey. A careful analysis of her twenty-one known stories suggests that they are indeed important (not merely peripheral to the novels and criticism) and are successful in developing specific techniques and themes germane to her total canon. -

The Critical and Artistic Reception of Beethoven's

THE CRITICAL AND ARTISTIC RECEPTION OF BEETHOVEN’S STRING QUARTET IN C♯ MINOR, OP. 131 Megan Ross A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Annegret Fauser Aaron Harcus Mark Katz ©2019 Megan Ross ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Megan Ross: The Critical and Artistic Reception of Beethoven’s String Quartet in C♯-Minor, Op. 131 (Under the direction of Mark Evan Bonds) Long viewed as the unfortunate products of a deaf composer, Ludwig van Beethoven’s “late” works are now widely regarded as the pinnacle of his oeuvre. While the reception of this music is often studied from the perspective of multiple works, my dissertation offers a different perspective by examining in detail the critical and artistic reception of a single late work, the String Quartet in C♯ minor, Op. 131. Critics have generally agreed that the string quartets best exemplify the composer’s late style, and that of these, Op. 131 stands out as the paradigmatic late quartet. I argue that this is because Op. 131 exhibits the greatest concentration of features typically associated with the late style. It is formally unconventional, with seven movements of grotesquely different proportions, to be played continuously, without a pause, as if to insist on the unity of the whole. It conspicuously avoids a sonata-form movement until its finale, opening instead with an extended fugue; the sonata-form finale, in turn, quotes from the fugue, again reinforcing the notion of formal wholeness. -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83883-2 - The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf Jane Goldman Index More information Index 1917 Club 16 Austen, Jane 41, 42, 47, 76 Abdication Crisis 33 Pride and Prejudice 76 Action 74 autobiography 1–2 Addison 113 avant-garde 12, 13, 14, 17, 21, 25–6, Aeschylus 113 32, 36, 38, 50, 87, 94, 109, 133 Agamemnon 113 Africa 41, 82 Bagenal, Barbara 15 Albert Hall 12 Banfield, Ann 33, 135 Alexandra, Queen 70 Barrett, Eileen 134 Albee, Edward 35 Barrett, Miche`le 103, 122, 131, 133 allegory 46, 63, 70, 71, 75, 78, 115 Barrett-Browning, Elizabeth 24, 75, Allen, Walter 129, 138 76, 77 America 4, 34, 58 Barrie, J. M. 124 androgyny 50, 54, 59, 68, 73, 97, Battle of Britain 84 100–1, 130, 133 Bazin, Nancy Topping 130 antifascism 22–3, 26, 32 BBC 117 exhibitions 23 Beaverbrook, Lord 22 Annual International Conference on Beddingham 13 Virginia Woolf 125 Beer, Gillian 64, 75, 87, 132, 133 Antigone 41, 111 Beethoven, Ludwig van 70 anti-imperialism 14, 32, 75 Bell, Angelica 16, 21 anti-Semitism 30, 82 Bell, Clive 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 18, Apollo 68 29, 32, 41, 43, 130, 131, 132 Ariosto Art 15 Orlando Furioso 66–7 Old Friends 29, 138 Aristophanes 113 Bell, Julian 10, 24, 85 Aristotle 52 Bell, Quentin 12, 21, 29, 138 art 32, 33, 41, 52, 58, 61, 62, 75, 79, 82, Virginia Woolf: A Biography 10, 13, 83, 85, 93, 131 24, 27–9, 31, 32 Artists International Association 23 Bell, Vanessa (ne´e Stephen) 4, 5, 6–7, 8, Asheham House 13, 16 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, Athenaeum 49 21, 23, 24, 28, 32, 47, 50, 60, 70, Auden, W. -

Film Music and Film Genre

Film Music and Film Genre Mark Brownrigg A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Stirling April 2003 FILM MUSIC AND FILM GENRE CONTENTS Page Abstract Acknowledgments 11 Chapter One: IntroductionIntroduction, Literature Review and Methodology 1 LiteratureFilm Review Music and Genre 3 MethodologyGenre and Film Music 15 10 Chapter Two: Film Music: Form and Function TheIntroduction Link with Romanticism 22 24 The Silent Film and Beyond 26 FilmTheConclusion Function Music of Film Form Music 3733 29 Chapter Three: IntroductionFilm Music and Film Genre 38 FilmProblems and of Genre Classification Theory 4341 FilmAltman Music and Genre and GenreTheory 4945 ConclusionOpening Titles and Generic Location 61 52 Chapter Four: IntroductionMusic and the Western 62 The Western and American Identity: the Influence of Aaron Copland 63 Folk Music, Religious Music and Popular Song 66 The SingingWest Cowboy, the Guitar and other Instruments 73 Evocative of the "Indian""Westering" Music 7977 CavalryNative and American Civil War WesternsMusic 84 86 PastoralDown andMexico Family Westerns Way 89 90 Chapter Four contd.: The Spaghetti Western 95 "Revisionist" Westerns 99 The "Post - Western" 103 "Modern-Day" Westerns 107 Impact on Films in other Genres 110 Conclusion 111 Chapter Five: Music and the Horror Film Introduction 112 Tonality/Atonality 115 An Assault on Pitch 118 Regular Use of Discord 119 Fragmentation 121 Chromaticism 122 The A voidance of Melody 123 Tessitura in extremis and Unorthodox Playing Techniques 124 Pedal Point -

The String Quartet”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenEdition Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 50 | Spring 2008 Special issue: Virginia Woolf Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quartet” Émilie Crapoulet Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/690 ISSN : 1969-6108 Éditeur Presses universitaires d'Angers Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 juin 2008 ISSN : 0294-04442 Référence électronique Émilie Crapoulet, « Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quartet” », Journal of the Short Story in English [En ligne], 50 | Spring 2008, mis en ligne le 01 juin 2011, consulté le 01 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/690 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 1 mai 2019. © All rights reserved Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quar... 1 Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quartet” Émilie Crapoulet “its [sic] music I want; to stimulate & suggest” (Woolf 1978a: 320) 1 From an author who felt that “the only thing in this world is music - music and books and one or two pictures” (1975: 41), and who, in her earliest years, humorously toyed with the idea of founding a colony “where there shall be no marrying - unless you happen to fall in love with a symphony of Beethoven” (1975: 41-42), it is hardly surprising that music was an art which directly inspired Virginia Woolf’s own literary compositions, playing a central role in her work as a writer. -

Of Mice and Men (I)

UNIT-1 STEINBECK: OF MICE AND MEN (I) Structure 1.0 Objective 1.1 Introduction 1.2 John Steinbeck: A Biographical Sketch 1.3 Of Mice and Men 1.3.1 Plot Summary 1.4 Chapterwise Summary and Analysis 1.4.1 Chapter One 1.4.2 Chapter Two 1.4.3 Chapter Three 1.4.4 Chapter Four 1.4.5 Chapter Five 1.4.6 Chapter Six 1.5 Let Us Sum Up 1.6 Review Questions 1.7 Bibliography 1.0 Objective In this unit we shall study John Steinbeck’s famous novella Of Mice and Men. We shall give you a detailed summary of the novel chapter wise and make a critical analysis of each. 1.1 Introduction Of Mice and Men is a novella written by Nobel Prize-winning author John Steinbeck. Published in 1937, it tells the tragic story of George Milton and Lennie Small, two displaced migrant ranch workers during the Great Depression in California. Based on Steinbeck’s own experiences as a bindle stiff in the 1920s (before the arrival of the Okies he would vividly describe in The Grapes of Wrath), the title is taken from Robert Burns’s poem, To a Mouse, which read: “The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men / Gang aft agley.” Required reading in many high schools, Of Mice and Men has been a frequent target of censors for what some consider offensive and vulgar language; consequently, it appears on the American Library 1 Association’s list of the Most Challenged Books of 21st Century. 1.2 John Steinbeck: A Biographical Sketch John Steinbeck was born in Salinas, California, on February 27, 1902 of German and Irish ancestry. -

The Unveiling of the Soul at Work in Virginia Woolf's "Mrs. Dalloway"

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1994 "Musing among the vegetables"| The unveiling of the soul at work in Virginia Woolf's "Mrs. Dalloway" Margaret Leigh Tillman The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Tillman, Margaret Leigh, ""Musing among the vegetables"| The unveiling of the soul at work in Virginia Woolf's "Mrs. Dalloway"" (1994). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1433. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1433 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TiLtMAN Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montaxia Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes " or "No " and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's .Signature tV) TiTi \ Date: ^ 1^^^ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undeitaker only with the author's exnlicit consent "MUSING AMONG THE VEGETABLES": The Unveiling of the Soul at Work in Virginia Woolf's Mrs,Dalloway by Margaret Leigh Tillman B.A., College of William and Mary, 1988 M.F.A., University of Montana, 1994 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1994 Approved by of Examiners Dean, Graduate School If. -

Humor and Wit in Virginia Woolf's Writing

Moments of Laughter: Humor and Wit in Virginia Woolf’s Writing When reading Woolf’s work, it is easy to focus on the instances of death and the general sense of foreboding that one feels. Whether the reader knows anything biographical of Virginia Woolf or not, it is common to say that all her stories seem to be depressing and centered around death. Because this is such a natural response, it would not be very interesting to study all the references and allusions to death in her writing. After all, in each of her novels that we’ve read so far, a main character has died. It is much more interesting, instead, to look at Woolf’s humor and the way in which she incorporates this into her work. Humor and wit in Woolf’s work are often overlooked, as they tend to be overshadowed by the gloominess so often associated with her. One aspect of the brilliancy of her writing, however, is this combination of tragedy and humor. We can’t say that her work is all funny or all tragic, and it is this blurring of the genres that is important. Woolf’s wit and humor help us understand her writing. Her focus was on representing real life and reality, and reality is the combination of humor and tragedy. Before we look at this blurring and its importance, we should first look at some examples of humor and wit in Woolf’s work, starting with her first book. The Voyage Out was Woolf’s first novel, and it is a serious, rather traditional book.