Virginia Woolf Miscellany, Issue 93, Spring/Summer 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Journal of the Short Story in English, 50 | Spring 2008 Beyond the Boundaries of Language: Music in Virginia Woolf’S “The String Quar

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 50 | Spring 2008 Special issue: Virginia Woolf Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quartet” Émilie Crapoulet Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/690 ISSN : 1969-6108 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Rennes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 juin 2008 ISSN : 0294-04442 Référence électronique Émilie Crapoulet, « Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quartet” », Journal of the Short Story in English [En ligne], 50 | Spring 2008, mis en ligne le 01 juin 2011, consulté le 03 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/690 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 3 décembre 2020. © All rights reserved Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quar... 1 Beyond the boundaries of language: music in Virginia Woolf’s “The String Quartet” Émilie Crapoulet “its [sic] music I want; to stimulate & suggest” (Woolf 1978a: 320) 1 From an author who felt that “the only thing in this world is music - music and books and one or two pictures” (1975: 41), and who, in her earliest years, humorously toyed with the idea of founding a colony “where there shall be no marrying - unless you happen to fall in love with a symphony of Beethoven” (1975: 41-42), it is hardly surprising that music was an art which directly inspired Virginia Woolf’s own literary compositions, playing a central role in her work as a writer. Woolf’s early technical proficiency,1 -

Complete Production History 2018-2019 SEASON

THEATER EMORY A Complete Production History 2018-2019 SEASON Three Productions in Rotating Repertory The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity October 23-24, November 3-4, 8-9 • Written by Kristoffer Diaz • Directed by Lydia Fort A satirical smack-down of culture, stereotypes, and geopolitics set in the world of wrestling entertainment. Mary Gray Munroe Theater We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Südwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 October 25-26, 30-31, November 10-11 • Written by Jackie Sibblies Drury • Directed by Eric J. Little The story of the first genocide of the twentieth century—but whose story is actually being told? Mary Gray Munroe Theater The Moors October 27-28, November 1-2, 6-7 • Written by Jen Silverman • Directed by Matt Huff In this dark comedy, two sisters and a dog dream of love and power on the bleak English moors. Mary Gray Munroe Theater Sara Juli’s Tense Vagina: an actual diagnosis November 29-30 • Written, directed, and performed by Sara Juli Visiting artist Sara Juli presents her solo performance about motherhood. Theater Lab, Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts The Tatischeff Café April 4-14 • Written by John Ammerman • Directed by John Ammerman and Clinton Wade Thorton A comic pantomime tribute to great filmmaker and mime Jacques Tati Mary Gray Munroe Theater 2 2017-2018 SEASON Midnight Pillow September 21 - October 1, 2017 • Inspired by Mary Shelley • Directed by Park Krausen 13 Playwrights, 6 Actors, and a bedroom. What dreams haunt your midnight pillow? Theater Lab, Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts The Anointing of Dracula: A Grand Guignol October 26 - November 5, 2017 • Written and directed by Brent Glenn • Inspired by the works of Bram Stoker and others. -

Chekhov's Names 71 Creature-The Sea Gull," 14 As Nina Used to Be

Chekhov's Nam.es JOHN P. PAULS The funny names, the droll expressions, the comic phrases he invented have passed into Russian speech ... 1 THE MASTERFUL AUTHOR of provincial frustration, A.P. Chekhov (1860-1904), regarded his unique lyrical plays of inaction as comedies, including his last masterpiece, The Cherry Orchard (1904). Yet, some American critics recently wrote of Uncle Vanya (1897), which Chekhov himself described as only "scenes from country life," as being "totally tragic." 2 Perhaps this superficial inconsistency could be answered by the casual yet valid statement of Slonim: And while the young humorist yielded to his gaiety, the mature writer evinced a melancholy tolerance of human frailties. 3 As in real life, so in Chekhov's plays, the comic goes hand in hand with the tragic, so well manifested earlier in Gogol's works ("laughter through tears"). Generally speaking, Chekhov's characters, though often pathetic, lack the dignity and stature of traditional tragic characters. They are frequently a mixture of pity and sympathetic ridicule, and can hardly qualify as being truly tragic. 4 The basic theme of Chekhov's subtle dramas is that the life of the provincial neurotic intelligentsia is dull, boring and frustrating, especially in view of the fact· that the characters lack the inner resources to escape the trifles of life, and to make their existence more rewarding. There is little excitement in routine work, in playing cards out of boredom, in bickering with the family, or in drinking vodka out of frustration. Long before Sherwood Anderson or Sinclair Lewis, Chekhov probed the dullness of middle-class life and described boredom as the most prevalent disease of modern times. -

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf for Students of Modern Literature, the Works of Virginia Woolf Are Essential Reading

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf For students of modern literature, the works of Virginia Woolf are essential reading. In her novels, short stories, essays, polemical pamphlets and in her private letters she explored, questioned and refashioned everything about modern life: cinema, sexuality, shopping, education, feminism, politics and war. Her elegant and startlingly original sentences became a model of modernist prose. This is a clear and informative introduction to Woolf’s life, works, and cultural and critical contexts, explaining the importance of the Bloomsbury group in the development of her work. It covers the major works in detail, including To the Lighthouse, Mrs Dalloway, The Waves and the key short stories. As well as providing students with the essential information needed to study Woolf, Jane Goldman suggests further reading to allow students to find their way through the most important critical works. All students of Woolf will find this a useful and illuminating overview of the field. JANE GOLDMAN is Senior Lecturer in English and American Literature at the University of Dundee. Cambridge Introductions to Literature This series is designed to introduce students to key topics and authors. Accessible and lively, these introductions will also appeal to readers who want to broaden their understanding of the books and authors they enjoy. Ideal for students, teachers, and lecturers Concise, yet packed with essential information Key suggestions for further reading Titles in this series: Bulson The Cambridge Introduction to James Joyce Cooper The Cambridge Introduction to T. S. Eliot Dillon The Cambridge Introduction to Early English Theatre Goldman The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf Holdeman The Cambridge Introduction to W. -

Selected Works of Lu Hsun

7 =-t SELECTED 1{ORKS OF VO L[I ME FOU R Y,.rj\\r^r 1!a- r.-::4i r.ar\. SELECTED WORKS OF LU HSUN VOLUME FOUR i-, :'fir 4\. itr .y 2 Lu Hsun with his wife and son Taken in September 1933 FOREIGN LANGUAGES PRESS PEKING 1960 T EDITOR'S NOTE Translated by Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang 'Ihe essays in this volume come from four collections: Frinqed Literature* and three volumes of Essays of Chieh.-chieh-ting. Fringed Literature, a collection of sixty-one essays written in 1934, was first published in 1936. The thirty- six essays in the first series of Essagrs of Chieh-chieh-ting were also written in 1934, the forty-eight in the second series in 1935, and the thirty-five in the third series in 1936. The three collections of Essays oJ Chieh-chieh-ting were all published in July 1937 after Lu Hsun's death, the first two having been edited by Lu Hsun, the last by his wife Hsu Kuang-ping. Between 1934 and 1936, when the essays in this volume were written, the spearhead of Japanese invasion had struck south from the northeastern provinces to Pe- king and Tientsin. On April 17, 1934, the Japanese imperialists openly declared that China belonged to their sphere of influence. In 1935, Ho Ying-chin signed the Ho-Umezu Agreement whereby the Kuomin- tang government substantially surrendered China's sovereign rights in the provinces of Hopei and Chahar. In November of the same year, the Japanese occupied Inner Mongolia and set up a puppet "autonomous gov- ernment" there. -

Abstract Volume

T I I II I II I I I rl I Abstract Volume LPI LPI Contribution No. 1097 II I II III I • • WORKSHOP ON MERCURY: SPACE ENVIRONMENT, SURFACE, AND INTERIOR The Field Museum Chicago, Illinois October 4-5, 2001 Conveners Mark Robinbson, Northwestern University G. Jeffrey Taylor, University of Hawai'i Sponsored by Lunar and Planetary Institute The Field Museum National Aeronautics and Space Administration Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 LPI Contribution No. 1097 Compiled in 2001 by LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under Contract No. NASW-4574 with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, education, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any paper or portion thereof requires the written permission of the authors as well as the appropriate acknowledgment of this publication .... This volume may be cited as Author A. B. (2001)Title of abstract. In Workshop on Mercury: Space Environment, Surface, and Interior, p. xx. LPI Contribution No. 1097, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. This report is distributed by ORDER DEPARTMENT Lunar and Planetary institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113, USA Phone: 281-486-2172 Fax: 281-486-2186 E-mail: order@lpi:usra.edu Please contact the Order Department for ordering information, i,-J_,.,,,-_r ,_,,,,.r pA<.><--.,// ,: Mercury Workshop 2001 iii / jaO/ Preface This volume contains abstracts that have been accepted for presentation at the Workshop on Mercury: Space Environment, Surface, and Interior, October 4-5, 2001. -

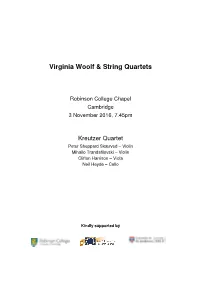

Virginia Woolf & String Quartets Concert

Virginia Woolf & String Quartets Robinson College Chapel Cambridge 3 November 2016, 7.45pm Kreutzer Quartet Peter Sheppard Skærved – Violin Mihailo Trandafilovski – Violin Clifton Harrison – Viola Neil Heyde – Cello Kindly supported by PREFACE Welcome to the third concert of ‘Virginia Woolf & Music’. The project explores the role of music in Woolf’s life and afterlives: it includes new commissions, world premieres and little-known music by women composers. Outreach activities and educational resources have been central to the project since it began in 2015. Concerts on Woolf and Bloomsbury continue throughout 2016- 17. For further details see: http://virginiawoolfmusic.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk Woolf (1882-1941) was a knowledgeable, almost daily, listener to ‘classical’ music, fascinated by the cultural practice of music and by the relationships between music and writing. Towards the end of her life she famously remarked, ‘I always think of my books as music before I write them’. Her writing continues to inspire composers who have set her words or responded more obliquely to her work. This concert takes its cue from Woolf’s extraordinary experimental short fiction, ‘The String Quartet’ (1921). The work explores the pleasures and frustrations of ‘capturing’ music in language. Juxtaposing the banal remarks that frame the performance with the exuberant flights of fancy that unfold during the playing, Woolf’s work celebrates music’s capacity to stimulate memories and associations. And it celebrates too music’s own ‘weaving’ into a formal ‘pattern’ and ‘consummation’. On 7 March 1920, Woolf attended a concert that included a Schubert quintet ‘to take notes for my story’. -

Elective English - III DENG202

Elective English - III DENG202 ELECTIVE ENGLISH—III Copyright © 2014, Shraddha Singh All rights reserved Produced & Printed by EXCEL BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi-110028 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara SYLLABUS Elective English—III Objectives: To introduce the student to the development and growth of various trends and movements in England and its society. To make students analyze poems critically. To improve students' knowledge of literary terminology. Sr. Content No. 1 The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 2 A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 3 Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 4 Ode to the West Wind by P.B.Shelly. The Vendor of Sweets by R.K. Narayan 5 How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 6 The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 7 Love Lives Beyond the Tomb by John Clare. The Traveller’s story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 8 Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 9 Next Sunday by R.K. Narayan 10 A Lickpenny Lover by O’ Henry CONTENTS Unit 1: The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 1 Unit 2: A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 7 Unit 3: Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 21 Unit 4: Ode to the West Wind by P B Shelley 34 Unit 5: The Vendor of Sweets by R K Narayan 52 Unit 6: How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 71 Unit 7: The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 84 Unit 8: Love Lives beyond the Tomb by John Clare 90 Unit 9: The Traveller's Story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 104 Unit 10: Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 123 Unit 11: Next Sunday by -

Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner Photographs, Negatives and Clippings--Portrait Files (A-F) 7000.1A

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c84j0chj No online items Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner photographs, negatives and clippings--portrait files (A-F) 7000.1a Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Hirsch. Data entry done by Nick Hazelton, Rachel Jordan, Siria Meza, Megan Sallabedra, and Vivian Yan The processing of this collection and the creation of this finding aid was funded by the generous support of the Council on Library and Information Resources. USC Libraries Special Collections Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California, 90089-0189 213-740-5900 [email protected] 2012 April 7000.1a 1 Title: Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner photographs, negatives and clippings--portrait files (A-F) Collection number: 7000.1a Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 833.75 linear ft.1997 boxes Date (bulk): Bulk, 1930-1959 Date (inclusive): 1903-1961 Abstract: This finding aid is for letters A-F of portrait files of the Los Angeles Examiner photograph morgue. The finding aid for letters G-M is available at http://www.usc.edu/libraries/finding_aids/records/finding_aid.php?fa=7000.1b . The finding aid for letters N-Z is available at http://www.usc.edu/libraries/finding_aids/records/finding_aid.php?fa=7000.1c . creator: Hearst Corporation. Arrangement The photographic morgue of the Hearst newspaper the Los Angeles Examiner consists of the photographic print and negative files maintained by the newspaper from its inception in 1903 until its closing in 1962. It contains approximately 1.4 million prints and negatives. The collection is divided into multiple parts: 7000.1--Portrait files; 7000.2--Subject files; 7000.3--Oversize prints; 7000.4--Negatives. -

Modern Sedimentation Patterns in Lake El'gygytgyn, NE Russia, Derived from Surface Sediment and Inlet Streams Samples V Wennrich University of Cologne

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 2013 Modern sedimentation patterns in Lake El'gygytgyn, NE Russia, derived from surface sediment and inlet streams samples V Wennrich University of Cologne Alexander Francke University of Wollongong, [email protected] A Dehnert Swiss Federal Nuclear Safety Inspectorate ENSI O Juschus Eberswalde University for Sustainable Development T Leipe Leibniz Institute For Baltic Sea Research See next page for additional authors Publication Details Wennrich, V., Francke, A., Dehnert, A., Juschus, O., Leipe, T., Vogt, C., Brigham-Grette, J., Minyuk, P. S., Melles, M. et al (2013). Modern sedimentation patterns in Lake El'gygytgyn, NE Russia, derived from surface sediment and inlet streams samples. Climate of the Past, 9 135-148. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Modern sedimentation patterns in Lake El'gygytgyn, NE Russia, derived from surface sediment and inlet streams samples Abstract Lake El'gygytgyn/NE Russia holds a continuous 3.58 Ma sediment record, which is regarded as the most long-lasting climate archive of the terrestrial Arctic. Based on multi-proxy geochemical, mineralogical, and granulometric analyses of surface sediment, inlet stream and bedrock samples, supplemented by statistical methods, major processes influencing the modern sedimentation in the lake were investigated. Grain-size parameters and chemical elements linked to the input of feldspars from acidic bedrock indicate a wind- induced two-cell current system as major driver of sediment transport and accumulation processes in Lake El'gygytgyn. -

Archetypal Figures in Mrs Dalloway

Modern Language Society ARCHETYPAL FIGURES IN "MRS DALLOWAY" Author(s): Jacqueline E. M. Latham Source: Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, Vol. 71, No. 3 (1970), pp. 480-488 Published by: Modern Language Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43342569 Accessed: 28-10-2019 13:19 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Modern Language Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Neuphilologische Mitteilungen This content downloaded from 143.107.3.152 on Mon, 28 Oct 2019 13:19:53 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 480 ARCHETYPAL FIGURES IN MRS D ALLOW AY Although Septimus Smith's recurring visions in Mrs Dalloway are clearly significant, no one has identified the elements of which they are composed. Two important image clusters frequently reappear; the first is centred on the figure of a man isolated and suffering: "His body was macerated until only the nerve fibres were left. It was spread like a veil upon a rock. He lay very high, on the back of the world."1 The second image has as its centre a drowned sailor and suggests that pain has given way to peace.