Sikkim Earthquake of 14 February 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notified Urban Areas for the Purpose of Implementing Various Schemes, Construction, Regulation of Buildings, Collection of Taxes and User Charges

GOVERNMENT OF SIKKJM URBAN DEVELOPMENT AND HOUSING DEPARTMENT GANCTOK N0. GOS/UD&HD/6(345)2005/3918 Dated: 19.02.2007 N O T I F I C A T I O N In exercise of the powers conferred by Sub-Section (2) of Section 7 of the Sikkim Allotment of House Sites and Construction of Building (Regulation and Control) Act, 1985 (Act No.11 of 1985) the State Government hereby declares the following bazaars as notified Urban Areas for the purpose of implementing various schemes, Construction, Regulation of buildings, collection of taxes and user charges. EAST DISTRICT Bazaar Class-I Gangtok, including Chandmari, Deorali and including Tadong, Rongneck, Burtuk, Bhojoghari, Syari, Tathangchen, Sichey and Arithang, Bazaar Class-II Rangpo, Ranipool, Pakyong Rhenock, Singtam and Rongli Bazaar Class-III Dikchu (E), Makha, Sang, Rorathang, Middle Camp 32 Nos, Penlong, Lingdok, Lingtam and Sirwani, Rural Marketing Centers Phadamchen, Kupup, Sherathang, Samdong, Ranka Central Pandam, Martam, Saramsa, Sumik Linzey, Tintek, Chandey Kyonglasla, Thegu, Lingtam, Jaluk, Sisney, Barapathing, Mamring, Machong, Chalisey, (Rhenock) Reshi(E), East Pendam, Kopchey, Dalapchand, Aritar, Chujachen, Rolep, Parakha, Rumtek, Lower Samdong, Duga and Tshongu. NORTH DISTRICT Bazar Class II Mangan Bazaar Class-III Dikchu (N), Phensong, Phodong and Chungthang. Rural Marketing Center Payong, Kabi, Namak, Ramthang, Singhik,Pakshep, Manuel, Naga Sangkalang, Hee-Gyathang, Pashingdong, Phidang, Tumlong, Phamtan, Bakcha, Lachen, Lachung, Linzya and Tingbong. SOUTH DISTRICT Bazar Class II Jorethang, Namchi, Melli, Ravongla Bazaar Class-III Simchuthang (Manglay), Majhitar, Temi Bazar, Damthang, Namthang, Kewzing, Yangang and Ralong. Rural Marketing Center Nandugoan, Tenzor, Maniram, Bhanjyang, Phungbhanjyang, Ratepaney, Tokal Bermiok, “O” Tarku, Ben Bazar, sadam, Melli Dara, Payong, Sukrabarey (sadam), Sumbuk, Turuk, Kitam, Wok, Lingmoo, Lingi Payong, Namphok, manpur, and Gumpa Gurpisey. -

ANSWERED ON:07.12.2015 Special Tourism Package for NER Misra Shri Pinaki;Sarmah Shri Ram Prasad

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA TOURISM LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:1252 ANSWERED ON:07.12.2015 Special Tourism Package for NER Misra Shri Pinaki;Sarmah Shri Ram Prasad Will the Minister of TOURISM be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government has any proposal to sanction Special Tourism Package for the North-Eastern region of the country; (b) if so, the details thereof and if not, the reasons therefor; and (c) the details of the number of tourists who visited the North-Eastern region during the last three years and current year? Answer MINISTER OF STATE FOR TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) (DR. MAHESH SHARMA) (a) and (b): No, Madam. Development and promotion of tourism is primarily the responsibility of the State Governments/UT Administrations. However, Ministry of Tourism provides Central Financial Assistance (CFA) to State Governments/Union Territory Administrations for various tourism projects subject to availability of funds, inter-se priority, liquidation of pending utilization certificates against the funds released earlier and adherence to the relevant scheme guidelines. Further, the following initiatives are taken by the Government of India to promote tourism in North Eastern Region: (i) Provision of complimentary space to the North Eastern States in India Pavilions set up at major International Travel Fairs and Exhibitions. (ii) 100% central financial assistance for organizing fairs & festivals is allowed to the North Eastern States. (iii) Ministry of Tourism, as part of its on-going activities, annually releases print, electronic, online and outdoor media campaigns in the international and domestic markets, under the Incredible India brand-line, to promote various tourism destinations and products of the country, including the lesser known destinations which have tourism potential. -

List of Jfmcs and Edcs in Sikkim

,©≥¥ ض *&-#≥ °Æ§ %$#≥ ©Æ 3©´´©≠ !≥ ØÆ *°Æ East Wildlife FDA S.No. JFMC/EDC President Member Secretary 1 Tsangu Shri Tamding Dhotopa RO (WL) Kyongnosla 2 Kyongnosla Shri Shyam Bdr. Gajmer RO (WL) Kyongnosla 3 Tumin Shri Lok Nath Sapkota ACF(WL) Fambonglho 4 Rakdong Shri Harka Bdr. Chettri ACF(WL) Fambonglho 5 Samdong Shri Nandi Kishore Nirola ACF(WL) Fambonglho 6 Simick Shri Jaga Nath Adhikari ACF(WL) Fambonglho 7 Martam Shri Rinzing Lama RO (WL) Fambonglho East 8 Sang Shri Phuchung Bhutia RO (WL) Fambonglho East 9 Ray Shri Rinchen Lepcha. RO (WL) Fambonglho East 10 Ranka Shri Bijay Rai RO (WL) Fambonglho East 11 Rumtek Shri Tshering Bhutia RO (WL) Fambonglho East 12 Pangthang Shri Shiva Kumar Chettri ACF(WL) Fambonglho 13 Regu Shri Nakul Rai ACF (WL) Pangolakha South 14 Dhalapchen Shri Mani Prasad Rai ACF (WL) Pangolakha South 15 Siganaybas Shri Mingmar Sherpa ACF (WL) Pangolakha South 16 Padamchen Shri Norbu Sherpa RO (WL) Pangolakha North Smt. Kalzang Dechen 17 Kupup RO (WL) Pangolakha North Bhutia 18 Gnathang-Zaluk Smt. Sonam Uden Bhutia RO (WL) Pangolakha North West Wildlife FDA S.No. JFMC/EDC President Member Secretary 1 Ribdi Shri Passang Dorjee Sherpa RO (WL) Barsey 2 Sombarey Shri Migma Sherpa RO (WL) Barsey 3 Soreng Shri Urgen Sherpa RO (WL) Barsey 4 Bermoik Martam Shri karma Sonam Sherpa RO (WL) Barsey 5 Hee Patal Shri Kenzang Bhutia RO (WL) Barsey 6 Dentam Shri Gyalpo Sherpa RO (WL) Barsey 7 Uttarey Shri Lal Bdr. Rai RO (WL) Barsey 8 Sribadam Shri Nanda Kr. Gurung RO (WL) Barsey 9 Okhrey Shri Sangay Shi Sherpa RO (WL) Barsey South Wildlife FDA S.No. -

India-China Border Trade Through Nathu La Pass: Prospects and Impediments

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 38 Number 1 Article 7 June 2018 India-China Border Trade Through Nathu La Pass: Prospects and Impediments Pramesh Chettri Sikkim University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Chettri, Pramesh. 2018. India-China Border Trade Through Nathu La Pass: Prospects and Impediments. HIMALAYA 38(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol38/iss1/7 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. India-China Border Trade Through Nathu La Pass: Prospects and Impediments Acknowledgements The author wishes to express his sincere gratitude to the peer reviewers for their valuable review of the article, and to Mark Turin, Sienna R. Craig, David Citrin, and Mona Bhan for their editorial support, which helped to give it the present shape. The author also wants to extend his appreciation to the Commerce and Industries and Tourism Department in the Government of Sikkim, to Sikkim University Library, and to the many local traders of Sikkim with whom he spoke while conducting this research. This research article is available in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol38/iss1/7 India-China Border Trade Through Nathu La Pass: Prospects and Impediments Pramesh Chettri This paper attempts to examine and analyze aspects, the Nathu La border trade has faced the prospects and impediments of the many problems. -

Mani Shankar Aiyar

Connectivity Issues in India’s Neighbourhood © Asian Institute of Transport Development, New Delhi. First published 2008 All rights reserved The views expressed in the publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations to which they belong or that of the Board of Governors of the Institute or its member countries. Published by Asian Institute of Transport Development 13, Palam Marg, Vasant Vihar, New Delhi-110 057 INDIA Phone: +91-11-26155309 Telefax: +91-11-26156294 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.aitd.net Contents Foreword i Connectivity: An Overview iii Perspectives on Northeast Connectivity 1 Mani Shankar Aiyar Imperatives of Connectivity 10 B. G. Verghese Connectivity and History: A Short Note 20 TCA Srinivasa-Raghavan India-China Connectivity: Strategic Implications 26 Gen. V. P. Malik Maritime Connectivity: Economic and Strategic Implications 36 Vijay Sakhuja Infrastructure, Northeast and Its Neighbours: Economic and Security Issues 66 Manoj Pant India-China Border Trade Connectivity: Economic and Strategic Implications and India’s Response 93 Mahendra P. Lama Connectivity with Central Asia – Economic and Strategic Aspects 126 Rajiv Sikri China’s Thrust at Connectivity in India’s Neighbourhood 146 TCA Rangachari Foreword The land and maritime connectivity have played a crucial role in political and economic evolution of the nation states. With a view to exploring the developments in this area in India’s neighbourhood, the Asian Institute of Transport Development held a one-day seminar on May 24, 2008 at India International Centre, New Delhi. The seminar was inaugurated by Hon'ble Mr. -

Disaster Management Plan-(2020-21) East Sikkim-737101

DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-(2020-21) EAST SIKKIM-737101 Prepared by: District Disaster Management Authority, East District Collectorate, East Sichey, Gangtok 1 FOREWORD Recent disasters, including the Earthquake which occurred on 18th September 2011 have compelled us to review our Disaster Management Plan and make it more stakeholders friendly. It is true that all the disasters have been dealt significantly by the state ensuring least damage to the human life and property. However, there is a need to generate a system which works automatically during crisis and is based more on the need of the stakeholders specially the community. Further a proper co-ordination is required to manage disasters promptly. Considering this we have made an attempt to prepare a Disaster Management Plan in different versions to make it more user-friendly. While the comprehensive Disaster Management Plan based on vulnerability mapping and GIS Mapping and minute details of everything related to management of disasters is underway, we are releasing this booklet separately on the Disaster Management Plan which is basically meant for better coordination among the responders. The Incident Command System is the part of this booklet which has been introduced for the first time in the East District. This booklet is meant to ensure a prompt and properly coordinated effort to respond any crisis. A due care has been taken in preparing this booklet, however any mistakes will be immediately looked into. All the stakeholders are requested to give their feedback and suggestions for further improvements. Lastly, I want to extend my sincere thanks to the Government, the higher authorities and the Relief Commissioner for the support extended to us and especially to my team members including ADM/R, SDM/Gangtok, District Project Officer and Training Officer for the hard work they have put in to prepare this booklet. -

Government of India Ministry of Tourism Lok Sabha

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF TOURISM LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.†3760 ANSWERED ON 19.03.2018 IDENTIFICATION OF TOURIST PLACES IN JHARKHAND †3760. SHRI RAM TAHAL CHOUDHARY: SHRI HARINARAYAN RAJBHAR: Will the Minister of TOURISM be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government has identified certain locations to be developed as tourist places in various States of the country during the last three years and if so, the details thereof, location-wise, State/UT- wise including Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar; (b) whether the Government has formulated any scheme/plan in this regard; and (c) if so, the details thereof and if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE FOR TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) (SHRI K.J. ALPHONS) (a) to (c): The Ministry of Tourism under its scheme of Swadesh Darshan- Integrated development of theme based tourist circuits has identified fifteen thematic circuits for development namely; North East Circuit, Buddhist Circuit, Himalayan Circuit, Coastal Circuit, Krishna, Circuit Desert Circuit, Tribal Circuit, Eco Circuit, Wildlife Circuit, Rural circuit, Spiritual Circuit, Ramayana Circuit, Heritage Circuit, Sufi Circuit and Tirthankar Circuit. Under the scheme of PRASHAD- National Mission on Pilgrimage Rejuvenation and Spiritual, Heritage Augmentation Drive, 25 sites have been identified for development namely Amaravati, Srisailam and Tirupati (Andhra Pradesh), Kamakhya (Assam), Patna and Gaya (Bihar), Dwarka and Somnath (Gujarat), Hazratbal and Katra (Jammu & Kashmir), Deogarh (Jharkhand), Guruvayoor (Kerala), Omkareshwar (Madhya Pradesh), Trimbakeshwar (Maharashtra), Puri (Odisha), Amritsar (Punjab), Ajmer (Rajasthan), Kanchipuram and Vellankani (Tamil Nadu), Varanasi, Ayodhya and Mathura (Uttar Pradesh), Badrinath and Kedarnath (Uttarakhand) and Belur (West Bengal). The State/UT-wise details of projects sanctioned under the above schemes including Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are annexed. -

Registered Ngo's in Sikkim

LIST OF ORGANISATION S.L.No. Name/Address Districts 1 Sikkim Soldiers' Rest House Comm. East Sikkim Gangtok, East Sikkim 2 Sikkimese Ex-Servicemen Asso. East Sikkim Gangtok, East Sikkim 3 Sikkim Social Welfare Society East Sikkim Gangtok, East Sikkim 4 National Spiritual Assembly Of Bahai's East Sikkim Gangtok, East Sikkim 5 Denzong Tashi Yargey East Sikkim Gangtok, East Sikkim 6 MIG Library East Sikkim Gangtok, East Sikkim 7 Orchids Musical Group East Sikkim Gangtok, East Sikkim 8 Sikkim Students' Association East Sikkim Delhi, Gangtok, East Sikkim 9 Sikkim Students' association East Sikkim Kalimpong, Gangtok, East Sikkim 10 Sasurali Pariwars East Sikkim West Point Gangtok, East Sikkim 11 SNT Drivers' Welfare Association East Sikkim Gangtok, East Sikkim 12 Sikkim Motor Transport Workers' Asso. East Sikkim Singtam, East Sikkim 13 Asamartha Sahayata Samity Duga, East sikkim East Sikkim 14 Youths' Library Gangtok, East Sikkim East Sikkim 15 Sarswati Library Tarethang, East Sikkim East Sikkim 16 Sikkim Small Farmers' Dev. Agency Gangtok, East Sikkim East Sikkim 17 Generation Gap Gangtok, East Sikkim East Sikkim 18 Sikkim Buddhist Association Gangtok, East Sikkim East Sikkim 19. Young Sikkim [Yuwa Sikkim] 20. Sikkim Byapari Sangh Gangtok, East Sikkim East Sikkim 21. Sikkim Govt. Employees' Asso. Gangtok, East Sikkim East Sikkim 22. Biswakarma Kaylan Samity Development Area, Gangtok, East Sikkim East Sikkim 23 Sikkim Mahila Kaylan Sangh Ranipool, East sikkim East Sikkim 24 Sangeet Kala Kendra Gangtok, East Sikkim East Sikkim 25 Himali Sangeet Sangh Gangtok, East Sikkim East Sikkim 26 Udvikas Kala Pratisthan Gangtok, East Sikkim East Sikkim 27 SNT Workers' Asso. Gangtok, East Sikkim East Sikkim 28 Army Wives' Welfare Asso. -

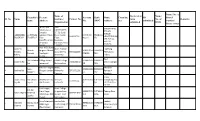

Sl. No Name Guardin's Name Present Address Name of Institute/ Organisation Contact No. Account No. Bank /IFSC Home Address Const

Name/ No. of Name of Decleration Name/ Guardin's Present Account Bank Home Constitue ID Hostel Sl. No Name Institute/ Contact No. form No. of Remarks name Address No. /IFSC Address ncy submitted warden/ Organisation submitted HOD House owner (B-301) Shri JAIN SINGITHANG, Balaji Sarovar, UNIVERSITY, BELOW Pattandur #17,Sheshadri PUBLIC ABHISHEK s/o PUNAM Agrahara Village Road, Gandhi 065350700 YESB0000 1 9008695790 GROUND,NAM PRADHAN PRADHAN Main Nagar, 002334 653 CHI-737126, Road,Whitefield, Bengaluru, SOUTH Bengaluru – Karnataka, India SIKKIM. 560066, – 560009 Near IAS Colony Aadarsh Alakh Prakash Lapthang Ganesh Sargeen Chowk 919010059 UTIB0003 2 Krishna Goyal Shimla 9593224605 Thekabung Sharma Panthgatti 976422 761 Kafley University Linkey Shimla East Dal Bahadur College Hostel HVPM College 379687635 SBIN0021 3 Aadarsh Rai 7602680858 Sikkim,Gangto Rai room no.6 Maharashtra 38 763 k Antriksh Height Amity Marchak Beeru 343033099 SBIN0008 4 Aaditya Rai Gurgaon sector University 9971591131 Ranipool Bangdel 55 287 84 Haryana Gangtok Amba Aadon Thing Nim Dorjee Dist.Mandi,Hima Abhilashi 2039812192 SBIN0009 Chungthang,Nea 5 7876300852 Lepcha Lepcha chal Pradesh University 1 036 r ICDS,Sikkim- 737133 Smithnagar, Doon College S/o Jag Prem Nagar of agriculture 918597571 PYTM012 Tadong Dara 6 Aaron Lepcha Tshering 8597571870 Dehradun,Uttra Science and 870 3456 Gaon Lepcha khand Technology Annafisher path Sanaka Edu Ladhaki Abhijeet Bishwa nath 867610100 CNRB000 7 Bidhanagar Trust Group of 7501810936 Mansion Vajra Sharma Sharma 8826 8676 West -

Total East Gangtok Sumin Lingzey Mangthang 18 2.89 133 21.38 195 31.3505 270 43.41 5 0.80 1 0.16 622 East Gangtok Sumin Lingzey

WARD-WISE POPULATION BY SOCIAL GROUP DistrictSub-Division GPU Ward Bhutia Lepcha Schedule Tribe Other Backward Class Most Backward Class Schedule Caste Unreserved Population Population % Population % Population % Population % Population % Population % Total East Gangtok Sumin Lingzey Mangthang 18 2.89 133 21.38 195 31.3505 270 43.41 5 0.80 1 0.16 622 East Gangtok Sumin Lingzey Upper Sumin 357 73.76 0 0.00 15 3.10 91 18.80 0 0.00 21 4.34 484 East Gangtok Sumin Lingzey Middle Sumin (Sumin Gumpa) 177 59.20 32 10.70 35 11.71 55 18.39 0 0.00 0 0.00 299 East Gangtok Sumin Lingzey Lower Sumin 82 13.10 111 17.73 347 55.43 65 10.38 13 2.08 8 1.28 626 East Gangtok Sumin Lingzey Lower Linzey 16 2.97 36 6.69 397 73.79 44 8.18 0 0.00 45 8.36 538 East Gangtok Sumin Lingzey Upper Lingzey 37 7.58 115 23.57 168 34.43 167 34.22 1 0.20 0 0.00 488 East Gangtok West Pendam Ralang 200 26.35 114 15.02 236 31.09 126 16.60 72 9.49 11 1.45 759 East Gangtok West Pendam Syapley 30 5.48 46 8.41 267 48.81 181 33.09 18 3.29 5 0.91 547 East Gangtok West Pendam Sakhu 16 2.47 18 2.78 431 66.51 127 19.60 38 5.86 18 2.78 648 East Gangtok West Pendam Khanigaon 0 0.00 56 9.02 277 44.61 197 31.72 90 14.49 1 0.16 621 East Gangtok West Pendam Singleybong 0 0.00 115 19.33 241 40.50 158 26.55 74 12.44 7 1.18 595 East Gangtok West Pendam Bordang 35 4.99 110 15.69 138 19.69 87 12.41 309 44.08 22 3.14 701 East Gangtok West Pendam Sawney 97 7.42 241 18.43 248 18.96 445 34.02 273 20.87 4 0.31 1308 East Gangtok Central Pendam Karmithang 0 0.00 53 6.91 576 75.10 36 4.69 59 7.69 43 5.61 -

SIKKIM PARYAVARAN MAHOTSAV, JUNE 15-30, 2016 DETAILS of SEEDLING DISTRIBUTION BOOTHS Sl District Range Location Contact No

SIKKIM PARYAVARAN MAHOTSAV, JUNE 15-30, 2016 DETAILS OF SEEDLING DISTRIBUTION BOOTHS Sl District Range Location Contact No. Remarks No Vajra/Gtk/Tathangchen 1 Zero point Resting Shed RO(T) Gangtok coverage area Chandmari Community Chandmari/Decheling/Ronge 2 RO(T) Gangtok Hall (Car Parking k/Bhusuk/Upper Chandmari Forest Secretariat, 3 RO(T) Gangtok Deorali/Syari/Tadong/NH 31 Deorali 4 5th mile, Tadong RO(T) Gangtok Lumsey/Samdur/Tadong Gangtok Lingdok/Penlong/Navey/Shot 5 Lingdok Forest Nursery RO(T) Gangtok ak 6 Makha RO(T) Gangtok Dikchu/Makha/Ralap Ranka/Lingdum/Sangtong/Pe 7 Lingdum Forest Nursery RO(T) Gangtok rbing/ Dhajey 8 Tumin Forest Check post RO(T) Gangtok Tumin/Namrang 9 Samdong RO(T) Gangtok 10 Lower Kambal RO(T) Gangtok 3rd Mile/4th Mile/6th 11 4th mile Nursery RO(T)Kyongnosla Mile/7th Mile 15th mile Police 12 Kyongnosla RO(T)Kyongnosla 15th Mile/Chipso Checkpost 13 Thegu RO(T)Kyongnosla Thegu/Yakla 14 Kupup RO(T)Kyongnosla Sherathang/Kupup 15 Khamdong BAC RO(T)Singtam Khamdong 16 Dipudara Dipudara/Thasa/Dungdung RO(T)Singtam 17 Sirwani RO(T)Singtam Sirwani Chisopani Singtam Forest 18 Singtam Checkpost RO(T)Singtam Singtam Bageykhola Forest 19 East Baghey/Bardang/Majhitar Nursery RO(T)Singtam 20 Rangpo Block Office RO(T)Singtam Rangpo 21 Duga BAC Duga/Central pendam/Sajong RO(T)Singtam 22 Sang Forest Nursery RO(T)Singtam Sang/Nazitam 23 Ranipul Forest Checkpost ROT() Ranipul Ranipul/Samdur 24 Rumtek ROT() Ranipul Rumtek/Sajong/Ray Mindu Ranipul 25 Block OfficeAssam Linzey ROT() Ranipul Nandok/Assam Gairigaon 26 Saramsa Garden ROT() Ranipul Saramsa East Sl District Range Location Contact No. -

Government of India Ministry of Tourism Lok Sabha

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF TOURISM LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.2204 ANSWERED ON 24.12.2018 SCHEME FOR UPGRADING SHANTINIKETAN 2204. DR. ANUPAM HAZRA: Will the Minister of TOURISM be pleased to state: (a) the role and responsibility of the Ministry of tourism relating to selecting and upgrading a tourist spot into an international tourist spot in any State in the country; (b) whether the Government has any projects/schemes for upgrading Shantiniketan in West Bengal into an international tourist spot; (c) if so, the details thereof; and (d) whether the Government has such projects/schemes for some other tourist spots within the country and, if so, the details thereof? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE FOR TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) (SHRI K.J. ALPHONS) (a): Identification and development of tourist sites/destinations is primarily the responsibility of the State Governments/Union Territory (UT) Administrations. However, Ministry of Tourism under the Schemes of Swadesh Darshan – Integrated Development of Theme Based Tourist Circuits and PRASHAD (National Mission on Pilgrimage Rejuvenation and Spiritual, Heritage Augmentation Drive) provides central financial assistance to State Governments/UT Administrations for the development of tourism infrastructure in the country. (b) and (c): The projects under the above schemes are identified for development in consultation with the State Governments/UT Administrations and are sanctioned subject to availability of funds, submission of suitable detailed project reports, adherence to scheme guidelines and utilization of funds released earlier. The Ministry of Tourism has not sanctioned any project for development of Shantiniketan in West Bengal under the above schemes. (d): The list of projects sanctioned under the Swadesh Darshan and PRASHAD schemes is given at the Annexure.