BY David Stick Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Hatteras National Seashore

05 542745 ch05.qxd 3/23/04 9:01 AM Page 105 CHAPTER 5 Cape Hatteras National Seashore Driving along Hatteras and Ocracoke islands national seashore and other nature preserves are on a narrow strip of sand with the ocean close wild and beautiful. Being here, it’s easy to on both sides, you may think that the Outer imagine what it was like when the first English Banks are a geographic miracle. Why should colonists landed more than 400 years ago, or this razor-thin rim of sand persist far out in the when the Wright brothers flew the first airplane sea? How wild it seems, a land of windy beach over a century ago. Both events are well inter- with no end, always in motion, always vulner- preted at their sites. The area is fascinating eco- able to the next, slightly larger wave. There’s so logically, too. Here, north and south meet, the much here to see and learn, and so much soli- mix of ocean currents, climate, fresh and salt tude to enjoy. You’re like a passenger on an water, and geography creating a fabulous diver- enormous ship, and unpredictable nature is the sity of bird and plant life at places like the Pea captain. Island National Wildlife Refuge (p. 124) and Oddly, many people don’t see Cape Hatteras Nags Head Woods Ecological Preserve (p. 124). this way. When they think of the Outer Banks, In this sense, the area is much like Point Reyes, they think of Nags Head or Kill Devil Hills, its counterpart on the West Coast, covered in towns where tourist development has pushed chapter 21, “Point Reyes National Seashore.” right up to the edge of the sea and, in many And for children, the national seashore is a places, gotten really ugly. -

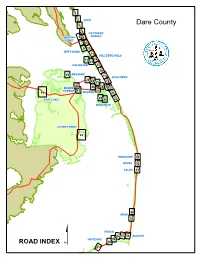

Road Index Books

1 2 DUCK 3 Dare County 4 SOUTHERN SHORES MARTINS 5 6 POINT 7 8 9 10 KITTY HAWK 11 KILL DEVIL HILLS 14 12 13 COLINGTON 15 16 45 MASHOES 17 NAGS HEAD 23 24 25 18 42 MANNS 26 28 19 20 HARBOR 43 27 46 MANTEO 21 EAST LAKE 29 30 22 WANCHESE STUMPY POINT 44 RODANTHE 31 WAVES 32 SALVO 33 34 AVON 35 FRISCO 38 37 36 BUXTON HATTERAS 39 ROAD INDEX $ 40 41 N BAUM TRL S BAUM TRL DUCK RD - NC 12 A B STATIONBAY DRIVE MARTIN LANE VIREO WAY QUAIL WAY GANNET WAXWING LANE LANE WAXWING GANNET COVE COURT HERON LN BLUE RUDDY DUCK LN PELICAN WAY TERNLN ROYAL LANE BUNTING SHEARWATER WAY BUNTING BUNTINGLN WAY C D SKIMMER WAY WAY SKIMMER OYSTER CATCHER LN SANDPIPERCOVE OCEAN PINES DRIVE FLIGHT DR OCEAN BAY BLVD CLAY ST ACORN OAK AVE SOUND SEA AVE MAPLE WILLOW DRIVE ELM DRIVE CYPRESS DRIVE DRIVE CEDAR DRIVE HILLSIDE COURT CARROL DR - SR 1408 ° Duck 1 CYPRESS CEDAR DRIVE WILLOW DRIVE DRIVE MAPLE DRIVE CARROL DR - SR 1408 CAFFEYS HILLSIDE COURT COURT SEA TERN DRIVE QUARTERDECK DRIVE TRINITIE DR MALLARD DRIVE COURT RENE DIANNE ST FRAZIER COURT A OLD SQUAW DRIVE SR 1474 BUFFELL HEAD RD - SR 1473 SPRIGTAIL DRIVE SR 1475 CANVAS BACK DRIVE SR 1476 WOOD DUCK DRIVE SR 1477 PINTAIL DRIVE SR 1478 WIDGEON DR - SR 1479 BALDPATE DRIVE WHISTLING B SWAN DR N SNOW GEESE DR S SNOW GEESE DR SPYGLASS ROAD SANDCASTLE SPINDRIFTLANE COURT COURT PUFFER NOR BANKS DR SAILFISH SNIPE CT COURT WINDSURFER COURT SUNFISH COURT DUCK ROAD - NC 12 C § DUCK VOLUNTEER FIRE DEPT D SANDY RIDGE ROAD 2 TOPSAIL COURT SPINNAKER MAINSAILCOURT COURT FORESAIL COURT WATCHSHIPS DR BARRIER ISLAND STATION Duck -

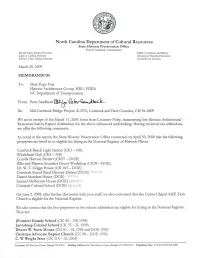

State Historic Preservation Office Peter B

North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Peter B. Sandbeck, Administrator Beverly Eaves Perdue, Governor Office of Archives and History Linda A. Carlisle, Secretary Division of Historical Resources Jeffrey J. Crow, Deputy Secretary David Brook, Director March 20, 2009 MEMORANDUM To: Mary Pope Furr Historic Architecture Group, HEU, PDEA NC Department of Transportation From: Peter Sandbeck Re: Mid-Cm-rituck Bridge Project, R-2576, Currituck and Dare Counties, CH 94-0809 We are in receipt of the March 11, 2009, letter from Courtney Foley, transmitting her Historic Architectural Resources Survey Report Addendum for the above referenced undertaking. Having reviewed the addendum, we offer the following comments. As noted in the report, the State Historic Preservation Office concurred on April 30, 2008 that the following properties are listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Girrituck Beach Light Station (CK1 — NR) Whalehead Club (CK5 — NR) Corolla Historic District (CK97 — DOE) Ellie and Blanton Saunders Decoy Workshop (CK99 — DOE) Dr. W. T. Griggs House (CK 103 — DOE) Currituck Sound Rural Historic District (DOE) Cle-01 09- Daniel Saunders House (DOE) (2,140 101 Samuel McHorney House (DOE) G4-00111 Coinjock Colored School (DOE) Oy_011,, On June 2, 2008, after further discussion with your staff, we also concurred that the Center Chapel A_ME Zion Church is eligible for the National Register. We also concur that the five properties in the subject addendum are eligible for listing in the National Register. They are: (Former) Grandy School (CK 40 — NR 1998) Jarvisburg Colored School (CK 55 — SL 1999) Dexter W. -

BUILDING Bridges to a Better Economy Viewfinder Ll 2007 Fa Eastthe Magazine of East Carolina University

2007 LL fa EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy BUILDING BrIDGes to a better economy vIewfINDer 2007 LL fa EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy 12 feaTUres BUilDing BriDges 12 Creating more jobs is the core of the university’s newBy Steve focus Tuttle on economic development. From planning a new bridge to the Outer Banks to striking new partnerships with relocating companies, ECU is helping the region traverse troubled waters. TUrning The PAGE 18 Shirley Carraway ’75 ’85 ’00 rose steadily in her careerBy Suzanne in education Wood from teacher to principal to superintendent. “I’ve probably changed my job every four or five years,” she says. 18 22 “I’m one of those people who like a challenge.” TeaChing sTUDenTs To SERVE 22 Professor Reginald Watson ’91 is determined toBy walkLeanne the E. walk,Smith not just talk the talk, about the importance of faculty and students connecting with the community. “We need to keep our feet in the world outside this campus,” he says. FAMILY feUD 26 As another football game with N.C. State ominouslyBy Bethany Bradsher approaches, Skip Holtz is downplaying the importance of the contest. And just as predictably, most East Carolina fans are ignoring him. DeParTMeNTs froM oUr reaDers 3 The eCU rePorT 4 26 FALL arTs CalenDar 10 BookworMs PiraTe naTion Dowdy student stores stocks books 34 for about 3,500 different courses and expects to move about one million textbooks into the hands of students during the hectic first CLASS noTes weeks of fall semester. Jennifer Coggins and Dwayne 37 Murphy are among several students who worked this summer unpacking and cataloging thousands of boxes of new books. -

Bibliography of North Carolina Underwater Archaeology

i BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH CAROLINA UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY Compiled by Barbara Lynn Brooks, Ann M. Merriman, Madeline P. Spencer, and Mark Wilde-Ramsing Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Division of Archives and History April 2009 ii FOREWARD In the forty-five years since the salvage of the Modern Greece, an event that marks the beginning of underwater archaeology in North Carolina, there has been a steady growth in efforts to document the state’s maritime history through underwater research. Nearly two dozen professionals and technicians are now employed at the North Carolina Underwater Archaeology Branch (N.C. UAB), the North Carolina Maritime Museum (NCMM), the Wilmington District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE), and East Carolina University’s (ECU) Program in Maritime Studies. Several North Carolina companies are currently involved in conducting underwater archaeological surveys, site assessments, and excavations for environmental review purposes and a number of individuals and groups are conducting ship search and recovery operations under the UAB permit system. The results of these activities can be found in the pages that follow. They contain report references for all projects involving the location and documentation of physical remains pertaining to cultural activities within North Carolina waters. Each reference is organized by the location within which the reported investigation took place. The Bibliography is divided into two geographical sections: Region and Body of Water. The Region section encompasses studies that are non-specific and cover broad areas or areas lying outside the state's three-mile limit, for example Cape Hatteras Area. The Body of Water section contains references organized by defined geographic areas. -

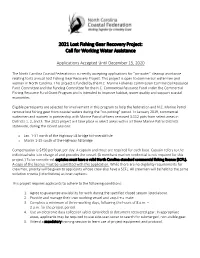

2021 Lost Fishing Gear Recovery Project: Call for Working Water Assistance

2021 Lost Fishing Gear Recovery Project: Call for Working Water Assistance Applications Accepted Until December 15, 2020 The North Carolina Coastal Federation is currently accepting applications for “on-water” cleanup assistance relating to its annual Lost Fishing Gear Recovery Project. This project is open to commercial watermen and women in North Carolina. This project is funded by the N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission Commercial Resource Fund Committee and the Funding Committee for the N.C. Commercial Resource Fund under the Commercial Fishing Resource Fund Grant Program and is intended to improve habitat, water quality and support coastal economies. Eligible participants are selected for involvement in this program to help the federation and N.C. Marine Patrol remove lost fishing gear from coastal waters during the “no-potting” period. In January 2019, commercial watermen and women in partnership with Marine Patrol officers removed 3,112 pots from select areas in Districts 1, 2, and 3. The 2021 project will take place in select areas within all three Marine Patrol Districts statewide, during the closed seasons: o Jan. 1-31 north of the Highway 58 bridge to Emerald Isle o March 1-15 south of the Highway 58 bridge Compensation is $450 per boat per day. A captain and mate are required for each boat. Captain refers to the individual who is in charge of and provides the vessel. (A merchant mariner credential is not required for this project.) To be considered, captains must have a valid North Carolina standard commercial fishing license (SCFL). A copy of the license must be submitted with this application. -

Supplemental Article to Where Is the Lost Colony?

Challenges to living by the sea A supplement to the serial story, Where is The Lost Colony? written by Sandy Semans, editor, Outer Banks Sentinel The thin ribbon of sand that forms the chain of islands known as the Outer Banks is bounded on the east by the Atlantic Ocean and on the west by the sounds. The shapes of the islands and the inlets that run between them continue to be altered by hurricanes, nor’easters and other weather events. Inlets that often proved to be moving targets created access to the ocean and the sounds. Inlets were formed and then later filled with sand and disappeared. Maps of the coastline show many places named “New Inlet,” although currently there is no inlet there. The one exception has been Ocracoke Inlet between Ocracoke and Portsmouth islands. Marine geologists estimate that the existing inlet — with some minor changes — has been in place for at least 2500 years. During the English exploration of the 1500’s, most likely the ships came through this inlet, making it a long sail to Roanoke Island. At that time, there was a small shallow inlet between Hatteras and Ocracoke islands, but the shallow inlet probably was avoided for fear of going aground. By the early 1700s, this inlet had filled in, and the two became just one long island. But in 1846, a hurricane created two major inlets. One, now called Oregon Inlet, sliced through the sand, leaving today’s Pea Island to the south and Bodie Island to the north. And a second inlet, now known as Hatteras Inlet, once again separated Hatteras Island from Ocracoke Island. -

An Historical Overviw of the Beaufort Inlet Cape Lookout Area of North

by June 21, 1982 You can stand on Cape Point at Hatteras on a stormy day and watch two oceans come together in an awesome display of savage fury; for there at the Point the northbound Gulf Stream and the cold currents coming down from the Arctic run head- on into each other, tossing their spumy spray a hundred feet or better into the air and dropping sand and shells and sea life at the point of impact. Thus is formed the dreaded Diamond Shoals, its fang-like shifting sand bars pushing seaward to snare the unwary mariner. Seafaring men call it the Graveyard of the Atlantic. Actually, the Graveyard extends along the whole of the North Carolina coast, northward past Chicamacomico, Bodie Island, and Nags Head to Currituck Beach, and southward in gently curving arcs to the points of Cape Lookout and Cape Fear. The bareribbed skeletons of countless ships are buried there; some covered only by water, with a lone spar or funnel or rusting winch showing above the surface; others burrowed deep in the sands, their final resting place known only to the men who went down with them. From the days of the earliest New World explorations, mariners have known the Graveyard of the Atlantic, have held it in understandable awe, yet have persisted in risking their vessels and their lives in its treacherous waters. Actually, they had no choice in the matter, for a combination of currents, winds, geography, and economics have conspired to force many of them to sail along the North Carolina coast if they wanted to sail at all!¹ Thus begins David Stick’s Graveyard of the Atlantic (1952), a thoroughly researched, comprehensive, and finely-crafted history of shipwrecks along the entire coast of North Carolina. -

Cape Fear Sail & Power Squadron

Cape Fear Sail & Power Squadron We are America’s Boating Club® NORTH CAROLINA OCEAN INLETS Listed in order of location north to south Oregon Inlet Outer Banks. Northern-most ocean inlet in NC. Located at the north end of New Topsail Inlet Near ICW Mile 270. As of July Hatteras Island. Provides access to Pamlico Sound. 7, ’20, the inlet was routinely passable by medium Federally maintained.* See Corps of Engineers and small vessels at higher states of the tide. survey1 However, buoys were removed in 2017 due to shoaling, so the channel is currently unmarked. See Hatteras Inlet Outer Banks. Located between Corps of Engineers survey Hatteras and Ocracoke Islands. Provides access to Pamlico Sound. Once inside the inlet itself, the Little Topsail Inlet Located ½ N.M. SW of New passage of a lengthy inshore channel is required to Topsail Inlet. Not normally passable and does not access the harbor or navigable portions of Pamlico currently connect to navigable channels inshore. Sound. Rich Inlet Located between Topsail and Figure 8 Ocracoke Inlet Outer Banks. Located at S end Islands near ICW Mile 275. of Ocracoke Is. Provides access to Pamlico Sound. Once inside the inlet itself, the passage of a shifting Mason Inlet Located between Figure 8 Island and inshore channel named Teaches Hole is required to Wrightsville Beach island near ICW Mile 280. access the harbor or navigable portions of Pamlico Dredged in 2019 but not buoyed as of July 31, ’20. Sound. Buoyed & lighted as of June 29, ’19. See Corps of Engineers surveys1 (for the inlet) and (for Masonboro Inlet Located between Wrightsville Teaches Hole). -

Tursiops Truncatus) Sighted in the Roanoke Sound, NC Jacquelyn Salguero

Delineating the northern extent of common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) sighted in the Roanoke Sound, NC Jacquelyn Salguero Introduction Common bottlenose dolphins (hereafter referred to as bottlenose dolphins), Tursiops truncatus, inhabit temperate and tropical waters across the world, including both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans of the United States (Rice, 1998). Within these regions, two main morphotypes of bottlenose dolphins can be distinguished: pelagic and coastal. In the western North Atlantic, along the Eastern United States, coastal populations are managed as distinct stocks, where a “stock” is defined as a group of animals that occupy the same area and interbreed (Rosel et al., 2009). Despite being highly mobile with a continuous range, coastal Atlantic bottlenose dolphins have been classified into two main ecotypes based on their primary habitat: “migratory coastal” found along the coastline and “estuarine” primarily residing in areas such as estuaries, bays, and harbors (Hayes et al., 2017, Toth et al., 2012). For management purposes, a number of estuarine stocks have been defined based on their spatial and temporal ranging patterns despite no clear spatial barrier to dispersal, migration, and gene flow (Rosel et al., 2009). This pattern of divergence without physical barriers, or sympatry, within inshore populations of bottlenose dolphins can also be seen in populations of bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops aduncus, in Moreton Bay, Australia. Significant genetic divergence was found along the small geographic region of Moreton Bay, showing patterns of fine-scale discrete population structuring depending on the varying water depths in the Southern and Northern regions of the bay (Ansmann et al., 2012). Another example of this overlapping spatial distribution within bottlenose dolphin populations can be found in Southern Georgia and Jacksonville, Florida estuarine systems which are approximately 80 km apart (Rosel et al., 2009). -

Occurrence, Distribution and Reproductive Status of Female Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops Truncatus) in Roanoke Sound, NC

Occurrence, Distribution and Reproductive Status of Female Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in Roanoke Sound, NC By Waverly Reibel Dr. Andrew J. Read, Advisor April 23rd, 2020 Master’s Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Environmental Management degree in the Nicholas School of the Environment of Duke University. Executive Summary I examined the spatial distribution of bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) nursery groups in Roanoke Sound, NC, to gain insight into how environmental parameters affect site fidelity, and to determine whether habitat use patterns change based on the reproductive state of females. I performed a home range analysis of mature females and compiled information on interbirth intervals and length of calf dependency to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the ecology and life history of this age and sex class of estuarine dolphins. I analyzed photo- identification survey data from Roanoke Sound collected over 11 years (2008-2019) to determine core usage areas of female bottlenose dolphins with respect to reproductive state. I compared the location and extent of kernel density estimates of home ranges for nursery groups and non- nursery groups. Many nursery groups are observed in this area during spring and summer, leading to the hypothesis that Roanoke Sound is an important nursery habitat. The importance of this area to lactating females may be attributable to its relatively shallow depth and abundant seagrass beds, which provide protection and a relatively plentiful supply of prey. In Roanoke Sound, nursery groups (n = 170) were significantly (p < 0.00001) larger than non-nursery groups (n = 68) with a mean of 12 individuals per sighting, while non-nursery groups had an average group size of 4 individuals. -

Manteo Harbor Report

A CULTURAL RESOURCE EVALUATION OF SUBMERGED LANDS AFFECTED BY THE 400TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION Manteo, North Carolina Conducted By Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources Richard W. Lawrence, Head Leslie S. Bright Mark Wilde-Ramsing Report Prepared by Mark Wilde-Ramsing November, 1983 Abstract Field investigations of the submerged bottom lands at Manteo, North Carolina were carried out by the Underwater Archaeology Branch, Division of Archives and History, Department of Cultural Resources. The purpose of these investigations was to identify historically and/or archaeologically significant cultural materials lying within the area to be affected by construction of a bridge and canal system and berthing area proposed for the 400th Anniversary Celebration (1984 to 1987) on Roanoke Island. Initially, a systematic survey of the project area was performed using a proton precession magnetometer to isolate magnetic disturbances, any of which might be generated by cultural material. Following this, a diving and probing search was conducted on isolated magnetic targets to determine the source. With the exception of the remains of a sunken vessel, Underwater Site #0001ROS, all magnetic disturbances were attributed to cultural debris of recent origin (twentieth century) and were determined historically and archaeologically insignificant. Recommendations for the sunken vessel located on the south side of the proposed berthing area are (1) complete avoidance of the site during construction activities, or (2) further