Lithuania Page 1 of 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gediminas Kirkilas

Gediminas Kirkilas Lituania, Primer ministro Duración del mandato: 04 de Julio de 2006 - de de Nacimiento: Vilnius, 30 de Agosto de 1951 Partido político: LSDP Profesión : Restaurador artístico y funcionario de partido ResumenLituania estrenó el 4 de julio de 2006 el undécimo primer ministro titular y el decimocuarto gobierno desde la independencia de la URSS en 1990, registros que reflejan el carácter fluido y muchas veces inestable del sistema de partidos de esta democracia parlamentaria. Vicepresidente del Partido Socialdemócrata (LSDP) y hasta ahora ministro de Defensa, Gediminas Kirkilas es un antiguo burócrata comunista cuya carrera política se ha desarrollado bajo el patrocinio del dimitido Algirdas Brazauskas, a quien sustituye en un gobierno de coalición rehecho con nuevos socios. Político moderado capaz de atraer apoyos en el arco ideológico del centroderecha, espera dejar al país listo para entrar en la eurozona poco después de terminar la actual legislatura en 2008. http://www.cidob.org 1 of 4 Biografía 1. Funcionario comunista reconvertido en socialdemócrata 2. Trayectoria como legislador y debut en el Gobierno 3. Sucesor de A. Brazauskas como segunda opción para el puesto de primer ministro 1. Funcionario comunista reconvertido en socialdemócrata El primogénito de los siete vástagos tenidos por un ingeniero y una maestra de escuela recibió la educación escolar en su Vilnius natal y en 1969 emprendió el servicio militar obligatorio en un buque de la Armada soviética. Vuelto a la vida civil en 1972, obtuvo su primer empleo como restaurador de mobiliario artístico, en particular molduras y objetos laminados en oro, en la plantilla del Fondo de Restauración y Conservación de Monumentos, órgano dependiente del Gobierno de la República Socialista Soviética Lituana (RSSL). -

Belarus' Relations with Ukraine and Lithuania Before and After the 2006

47 BELARUS’ RELATIONS WITH UKRAINE AND LITHUANIA BEFORE AND AFTER THE 2006 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS Dzianis Melyantsou, Andrej Kazakevich* Abstract This article contains an analysis of the changes in the Belarus’ foreign policy towards its immediate neighbours, Lithuania and Ukraine. Special attention is given to the analysis of reasons and conditions for such considerable changes in the Belarusian authorities’ policies, and the comparison of policies before and after the “reversal” that took place in 2005–2006. The “reversal” was caused by a number of factors, some of which are dependant on the peculiarities of the political development of Belarus such as the political isolation on the part of the West, the aggravation of relations with Russia, the presidential elections of 2006, and the strengthen- ing of the authoritarian regime. Other factors were of external and regional nature such as the coming into power of new political leaders in the Ukraine in 2004, and the growing acuteness of the energy security problem. For better or worse, the events of 2005–2006 have significantly altered the foreign policy orientation of Belarus, which promises both new challenges and new opportunities. 1. Belarus-Lithuania relations Until recently, Belarus-Lithuania relations remained in the shadow of the official relations between Minsk and Moscow, and only after the presidential elections in 2006 and the changes in the international context did relations between the two neighbouring countries become more dynamic and gain more importance for Belarus. This evolution of bilateral relations can firstly be -ex plained by the deterioration of Russia-Belarus relations, and the actual winding *Dzianis Melyantsou, MA in Political Science, analyst at the Belarusian Institute for Strategic Stu- dies (http://belinstitute.eu), e-mail: [email protected]; Andrej Kazakevich, political analyst, the Head of the Bachelor program “Political Science. -

DEMOCRACY in RUSSIA: MISSION POSSIBLE Andrius Kubilius, MEP EP Standing Rapporteur on Russia Former Prime Minister of Lithuania

NOT FOR SALE DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA: MISSION POSSIBLE Andrius Kubilius, MEP EP Standing Rapporteur on Russia Former Prime Minister of Lithuania COLLECTION OF ARTICLES 1 Democracy in Russia: Mission Possible Foreword Dreams are moving the World forward! The American Dream, since the very beginning of the American history, was a moving force for the American society. Ronald Reagan used to say that “America is too great for small dreams.” One of his great dreams led to the collapse of “the Evil Empire”. On the European continent (at least those of us who come from “the new Europe”), we live with a very clear and big dream of “Europe: whole, free and at peace”. This is a dream to live in the peaceful, stable and prosperous neighbourhood. We were fighting for that dream to become a reality since the very beginning of 1990s, when we were striving for our return to democracy and for our European integration. Unfortunately, fulfilment of the dream of “Europe: whole, free and at peace” is still an unfinished business. Part of the former Soviet Union is still suffering deprived of freedom, democracy and human rights. Today Russia is the biggest victim of that unfinished business and the Kremlin regime is the biggest obstacle for that dream to come true. The hybrid strategy of Putin towards the West was always based on attempts to convince the Western leaders that democracy is not suitable for Russia, which supposedly is a “special case”, because it was always ruled by czars, general secretaries or authoritarian presidents. Meanwhile in the West, there were and still are quite many of those who believe in this propaganda about Russia, and who repeat that democracy in Russia is impossible to achieve, and that the West should simply adapt to such a situation in the European continent. -

Lithuania by Aneta Piasecka

Lithuania by Aneta Piasecka Capital: Vilnius Population: 3.4 million GNI/capita: US$17,170 Source: The data above was provided by The World Bank, World Bank Indicators 2010. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Electoral Process 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Civil Society 1.75 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Independent Media 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Governance* 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.75 2.75 Local Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 Judicial Framework and Independence 1.75 2.00 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.50 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Corruption 3.75 3.75 3.50 3.50 3.75 4.00 4.00 3.75 3.75 3.50 Democracy Score 2.21 2.21 2.13 2.13 2.21 2.21 2.29 2.25 2.29 2.25 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

India-Lithuania Relations

India-Lithuania Relations Political Relations: It is widely acknowledged that there is a close similarity between the Lithuanian and Sanskrit languages, Lithuanian being the Indo-European language grammatically closest to Sanskrit, signifying possible close ancient links. Until conversion to Christianity in 13th century, the people in Lithuania worshipped nature and had a trinity of gods - Perkunas, Patrimpas, and Pikuolis. In more recent times, the first direct knowledge about India reached Lithuania through Lithuanian Christian missionaries who started serving in India since the 16th century. One of the prominent Lithuanian philosophers and ideologists of the 19th century national movement, Vydunas (real name Vilhelmas Storost, 1868-1953; also known as the Mahatma Gandhi of Lithuania) was extremely interested in Indian philosophy and he even created his own philosophical system closely based on the Vedanta. He practised Ayurveda. He argued that before the introduction of Christianity, Lithuanian spiritual culture had a lot of similarities with Hinduism, including the concept of Trinity. Diplomatic Relations: India recognized Lithuania (along with the other Baltic States of Latvia and Estonia) on 7th September 1991 after acceptance of their independence by the erstwhile USSR. Diplomatic relations were established with Lithuania on 25th February 1992. Lithuania opened its Embassy in New Delhi on July 1, 2008 and has an Honorary Consul in Mumbai. An Indian Mission in Vilnius is under consideration. Bilateral Visits: From India: MOS for External Affairs Mrs Preneet Kaur visited Vilnius from March 26-29, 2011. MOS Mrs Preneet Kaur again visited Vilnius on 30 June-02 July 2011 to attend the Ministerial meeting of Community of Democracies. -

General Elections in Lithuania on 11 and 25 October

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN LITHUANIA 11-25TH OCTOBER 2020 European The Farmers and Greens Party Elections monitor (LVZS), led by outgoing Prime Corinne Deloy Minister Saulius Skvernelis, could remain in office after the general election in Lithuania ANALYSIS At the beginning of April, while Lithuanians were in Political observers expect little change in the voting on lockdown the President of the Republic Gitanas Nauseda October 11 and 25. They anticipate that negotiations announced that his fellow-citizens would be called to over a future governing coalition will be lengthy. It could ballot on October 11 and 25 to renew the 141 elected also be unstable. MPs of the Seimas, the only house of parliament. 22 According to the latest opinion poll conducted by the political parties are competing in these parliamentary Spinter Tyrimai Institute, the Homeland Union-Christian elections, 332 people, including 282 affiliated to a Democrats (TS-LKD), the main opposition party led by party and 38 who are running as independents, are Gabrielius Landsbergis, is due to come out ahead with candidates. 21.7% of the vote. It is expected to be followed by the Farmers and Greens Party with 19.4%, the Social Lithuania is governed by a coalition government led by Democratic Party with 12.6%, and the Labour Party Prime Minister Saulius Skvernelis, which includes the with 8.6%, followed by the Freedom Party (Laisves), a LVZS and the Social Democratic Labour Party (LSDDP) social-liberal party led by Ausrinė Armonaite with 6.8% of Gediminas Kirkilas. The government is supported and the Liberal Movement (LRLS) of Eugenijus Gentvilas by “Welfare Lithuania” and the Electoral Action for with 5.9%. -

Lithuania by Aneta Piasecka

Lithuania by Aneta Piasecka Capital: Vilnius Population: 3.4 million GNI/capita: US$14,550 The social data above was taken from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s Transition Report 2007: People in Transition, and the economic data from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators 2008. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Electoral Process 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Civil Society 2.00 1.75 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.75 1.75 Independent Media 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Governance* 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic 2.50 Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a 2.50 2.50 2.50 Local Democratic 2.50 Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a 2.50 2.50 2.50 Judicial Framework 1.75 and Independence 2.00 1.75 2.00 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.50 1.75 Corruption 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.50 3.50 3.75 4.00 4.00 3.75 Democracy Score 2.29 2.21 2.21 2.13 2.13 2.21 2.21 2.29 2.25 * With the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

An Open Letter To

VILNIUS, JULY 2008 AN OPEN LETTER TO HIS EXCELLENCY VALDAS ADAMKUS, PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA CESLOVAS JURSENAS, SPEAKER OF THE SEIMAS OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA GEDIMINAS KIRKILAS, PRIME MINISTER OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA ALGIMANTAS VALANTINAS, PROSECUTOR GENERAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA The prosecutors of Lithuania do not cease to persecute anti-Nazi Jewish partisans. The Prosecution Service’s claims that “hundreds of witnesses are being questioned” are belied by the fact that only Jewish names are being heard in the media: Yitzhak Arad, Fania Brantsovsky, Rachel Margolis, and others. This enables us to conclude that efforts are being made in order to shape Lithuanian public opinion by portraying Jews as primarily responsible for the crimes of the Soviet totalitarian regime. The negative image of anti-Nazi Jewish partisans is being consciously constructed in the mass media. For example, an officer from the Prosecution Service said in public that a search for Fania Brantsovsky was allegedly announced, although this former ghetto prisoner and anti-Nazi partisan has lived in Vilnius for more than 80 years and has a permanent job. We feel that it is our duty to remind the public that the anti-Nazi Jewish partisans were prisoners of the ghettos that had been established by the Nazis and their Lithuanian collaborators, and survived only because they fought an armed fight against Hitlerism. By fighting against Nazism they saved Lithuania’s honor in World War II, and contributed to the Allied forces’ victory against Nazi Germany. During the Nazi occupation, the Nazis and their local collaborators killed more than 220,000 Jews; they destroyed the Lithuanian Jewish community almost completely. -

Lithuania: a Case Study

Adopting the Euro in Midst of Crisis Lithuania: a Case Study Julianne Maila A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies University of Washington Spring 2015 Committee Guntis Smidchens, Chair MiChelle Turnovsky Program authorized to offer degree: Henry M. JaCkson SChool of International Studies ©Copyright 2015 Julianne Maila 2 University of Washington Abstract Adopting the Euro in the Midst of Crisis Lithuania: a Case Study Julianne Maila Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Guntis SmidChens Scandinavian Studies Lithuania has been one of only three nations to adopt the euro sinCe the global finanCial Crisis roCked the world and tested the viability of the Eurozone as a single CurrenCy union. Despite unCertainty about the future of the euro, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia went forward with adoption. This paper examines Lithuania’s road to the euro from 2004, when it joined the European Union, through to entry into the Eurozone on January 1, 2015. It summarizes the costs and benefits of Economic Monetary Union from both an eConomiC and politiCal standpoint, and analyzes the actions and statements of key players – the government, the organized opposition, the Central bank and the general publiC – and their influenCe on the adoption proCess in Lithuania. 3 Table of Contents SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 RESEARCH QUESTIONS ........................................................................................................................... -

2010 M. Liepa Nr

2010 m. liepa Nr. 5 Laikraštis, tęsiantisXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX šimtmetines tradicijas. Leidžiamas nuo XX a. pradžios. PRO MEMORIA ALGIRDUI BRAZAUSKUI Birželio 26 dieną po ilgos ir sunkios ligos lėmė tuo metu gyventi ir dirbti. Mūsų šalis pirmą sykį reiškė nuoširdų solidarumą rinis vaidmuo. 1990 m. kovo 17 d. Lietuvos mirė Lietuvos Nepriklausomos Valstybės toli gražu nebuvo užsikonservavusi, žmonių „partinėms skyryboms“. Respublikos Aukščiausiosios Tarybos buvo Atkūrimo Akto signataras, 1992 – 1993 m. išsilavinimu ir jų profesiniais gebėjimais, 1990 m. sausio 15 d. A. Brazauskas iš- patvirtintas Lietuvos Respublikos Ministro Seimo Pirmininkas, ėjęs Respublikos Prezi- mokslo raida rinktas Lietuvos Pirmininko pavaduotoju. Nepriklausomos dento pareigas, 1993 – 1998 metų kadenci- pernelyg neatsi- TSR Aukščiau- Lietuvos pirmosios Vyriausybės laukė di- jos Lietuvos Respublikos Prezidentas, XII liko nuo laisvų siosios Tarybos deli darbai. Tai buvo akivaizdus Sąjūdžio ir ir XIII Vyriausybių Ministras Pirmininkas Europos tautų. Į Prezidiumo Pir- savarankiškos LKP bendradarbiavimo pa- Algirdas Brazauskas. naują nepriklau- mininku. Vasario vyzdys. Daug rūpesčių ir įtampos pareika- Savo aukščiausią pareigybę jis įvardino somo gyvenimo 7 d. jo vadovau- lavo TSRS ekonominė blokada, kurios tiks- kaip tarnystę tautai ir valstybei: „Valdžią tarpsnį ji įžengė jama LTSR Aukš- las buvo sustabdyti Lietuvos siekį gyventi suprantu kaip didžiausią atsakomybę. Tik turėdama gana čiausioji Taryba nepriklausomai ir sugriauti šalies ūkį. Kaip savo protu, darbštumu, didelėmis valios apsišvietusią vi- priėmė nutari- pastebėjo pats A. Brazauskas: „Būdami ne- pastangomis galime sukurti klestinčią Lie- suomenę...“ mą, panaikinantį priklausomi, dirbome priklausomoje aplin- tuvos valstybę, kurioje būtų gera ir sau- 1988 m., pra- 1940 m. liepos koje, tačiau tvarkėmės taip, kad kuo mažiau gu gyventi kiekvienam piliečiui.“ Tiesos sidėjus tauti- 21 d. -

Konservatorių Ir Socialdemokratų Derybos — Vangios

THE LITHUANIAN WORLD-WIDE DAILY Kaina 50 c KETVIRTADIENIS - THURSDAY, BIRŽELIO - JUNE 8, 2006 Vol. XCVII Nr. 110 Konservatorių ir socialdemokratų derybos — vangios kandžias replikas ir pastabas. Žurnalistams paklausus, kaip Susitikime konservatoriai įteikė vertina tai, kad derybose dalyvauja socialdemokratams susitarimo pro įtakingas socialdemokratas, artimas jektą, kuriame numatyta, kad koali Algirdo Brazausko bendražygis Juo cijoje negali būti susikompromitavu zas Bernatonis, apie kurį konserva sios Darbo partijos ir liberaldemok- toriai nėra labai geros nuomonės, A. ratų bei kita esminė konservatorių Kubilius teigė, jog „tai yra tam tikro sąlyga — „derybų pirmosios inicia požiūrio demonstravimas". tyvos teisė priklauso Seime di Tačiau G. Kirkilas replikavo: džiausią frakciją turinčiai Tėvynės „Norėčiau tokį įvertinimą užsitar Sąjungos frakcijai". nauti, kaip J. Bernatonis. Reiškia, „Konservatoriai jau anksčiau jog geras derybininkas, jei konserva laiko perdavė pasiūlymus. Tai aš toriai jo nenori". Nukelta į 6 psl. jiems patarčiau nežlugdyti derybų tokiais žaidimais. Mes dabar turime užsidaryti ir sėdėti, o žiniasklaidai apie rezultatus visada spėsime pra Šiame nešti, nes toks derybų stilius, mano požiūriu, nelabai tinka", — piktinosi numeryje: kitas socialdemokratų derybininkas, Politikai (iš kairės): Andrius Kubilius, Juozas Olekas ir Gediminas Kirkilas •Lietuvių telkiniuose. prieš susitikimą su prezidentu. Olgos Posaškovos (ELTA) nuotr. krašto apsaugos ministras Gedimi nas Kirkilas. •Kad šuo kepsnio Vilnius, birželio 7 d. (BNS) — Vis dėlto trečiadienį po susitiki Savo ruožtu, konservatorių va nenuneštų. Konservatoriai ir socialdemokratai mo su prezidentu Valdu Adamkumi dovas Andrius Kubilius, padėkojęs •„Apnėštėjimas" nauju tikina planuojantys pradėti derybas per spaudos konferenciją žiniask- už „pamokymus", teigė, jog apie dėl valdančiosios daugumos „nuo laidai konservatorių ir socialdemok- koalicijos sudarymo sąlygas buvo Seimu? balto lapo" ir be išankstinių sąlygų. ratų derybininkai laidė vienas kitam kalbama ir anksčiau. -

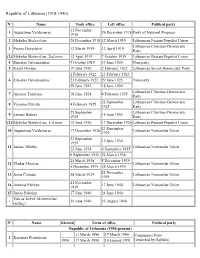

List of Prime Ministers of Lithuania

Republic of Lithuania (1918-1940) Nº Name Took office Left office Political party 11 November 1 Augustinas Voldemaras 26 December 1918 Party of National Progress 1918 2 Mykolas Sleževičius 26 December 1918 12 March 1919 Lithuanian Peasant Populist Union Lithuanian Christian-Democratic 3 Pranas Dovydaitis 12 March 1919 12 April 1919 Party (2) Mykolas Sleževičius, 2nd term 12 April 1919 7 October 1919 Lithuanian Peasant Populist Union 4 Ernestas Galvanauskas 7 October 1919 19 June 1920 Non-party 5 Kazys Grinius 19 June 1920 2 February 1922 Lithuanian Social-Democratic Party 2 February 1922 23 February 1923 6 Ernestas Galvanauskas 23 February 1923 29 June 1923 Non-party 29 June 1923 18 June 1924 Lithuanian Christian-Democratic 7 Antanas Tumėnas 18 June 1924 4 February 1925 Party 25 September Lithuanian Christian-Democratic 8 Vytautas Petrulis 4 February 1925 1925 Party 25 September Lithuanian Christian-Democratic 9 Leonas Bistras 15 June 1926 1925 Party (2) Mykolas Sleževičius, 3rd term 15 June 1926 17 December 1926 Lithuanian Peasant Populist Union 23 September 10 Augustinas Voldemaras 17 December 1926 Lithuanian Nationalist Union 1929 23 September 12 June 1934 1929 11 Juozas Tūbelis Lithuanian Nationalist Union 12 June 1934 6 September 1935 6 September 1935 24 March 1938 24 March 1938 5 December 1939 12 Vladas Mironas Lithuanian Nationalist Union 5 December 1939 28 March 1939 21 November 13 Jonas Černius 28 March 1939 Lithuanian Nationalist Union 1939 21 November 14 Antanas Merkys 17 June 1940 Lithuanian Nationalist Union 1939 15 Justas