Games and Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theescapist 055.Pdf

in line and everything will be just fine. two articles I fired up Noctis to see the Which, frankly, is about how many of us insanity for myself. That is the loneliest think to this day. With the exception of a game I’ve ever played. For those of you who fell asleep during very brave few. the classical mythology portion of your In response to “Development in a - Danjo Olivaw higher education, the stories all go like In this issue of The Escapist, we take a Vacuum” from The Escapist Forum: this: Some guy decides he no longer look at the stories of a few, brave souls As for the fact that thier isolation has In response to “Footprints in needs the gods, sets off to prove as in the game industry who, for better or been a benefit to them rather than a Moondust” from The Escapist Forum: much and promptly gets smacked down. worse, decided that they, too, were hindrance, that’s what I discussed with I’d just like to say this was a fantastic destined to make their dreams a reality. Oveur (Nathan Richardsson) while in article. I think I’ll have to read Olaf Prometheus, Sisyphus, Icarus, Odysseus, Some actually succeeded, while others Vegas earlier this year at the EVE the stories are full of men who, for crashed and burned. We in the game Gathering. The fact that Iceland is such whatever reason, believed that they industry may not have jealous, angry small country, with a very unique culture were not bound by the normal gods against which to struggle, but and the fact that most of the early CCP constraints of mortality. -

(With) Videogame History Moving Beyond Retrogaming Ahm, Kristian Redhead

(Re)Playing (with) Videogame History Moving Beyond Retrogaming Ahm, Kristian Redhead Publication date: 2018 Citation for published version (APA): Ahm, K. R. (2018, Sep 12). (Re)Playing (with) Videogame History: Moving Beyond Retrogaming. https://www.academia.edu/37325146/_Re_Playing_with_Videogame_History_Moving_beyond_Retrogaming Download date: 26. sep.. 2021 (Re)Playing (with) Videogame History Moving beyond Retrogaming by Kristian Redhead Ahm Master’s Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in IT – Games At The IT-University of Copenhagen, Center for Computer Games Research September 2018 Under the Supervision of Associate Professor Hans-Joachim Backe Resumé Forfatteren af dette speciale har foretaget en kvalitativ undersøgelse, hvor 9 spillere af gamle spil, også kaldet retrogamere, er blevet interviewet om deres motivationer for at spille gamle spil, hvordan de spiller dem og hvor længe. Ved at indtage et fænomenologisk ståsted, ønsker dette speciale at undersøge, hvordan disse gamle spil manifesterer sig i respondenternes livsverdener og hvad dette indebærer for deres opfattelse og brug af disse gamle spil. Denne undersøgelse er blevet betragtet som frugtbar, da den kan problematisere og videreudvikle den nuværende akademiske diskurs omkring retrogaming, der reducerer alle nutidige interaktioner med gamle spil til en aktivitet, der er motiveret af nostalgi. Ved at analysere de indsamlede interviewdata, argumenteres der i dette speciale for, at der eksisterer flere motivationer til at spille gamle spil, udover nostalgi. Dette speciale identificerer fire motivationer udover nostalgi. Den første type, kaldet amatørarkæologen, er interesseret i at spille ”dårlige” og kuriøse gamle spil, på grund af en form for ironisk nydelse og historisk nysgerrighed. -

Deus Ex (2000) by Ion Storm Inc

A zeitgeist game is reflective of its corresponding social climate. Titles that gain zeitgeist status have in some way challenged the norms of their associated era and revolutionised a pre-established genre by bending traditional conventions. Thus, zeitgeist titles are also timeless. They transcend time, remaining popular and famous due to the societal standpoints they raise and the impact their innovation has on the wider gaming communities and markets. Sci-Fi cyberpunk FPS/RPG Deus Ex (2000) by Ion Storm Inc. is an example of one such title that has built upon its sociological, artistic and technical influences to create a game that resonates innovation through its unique application of emergent gameplay; driven by character interaction and choice. Through analysis of these three fundamental influences in relation to the unique emergent gameplay construction of Deus Ex and correspondingly by comparing the game with its peers gives insight into how this game achieved zeitgeist status. Deus Ex was not the first game to challenge the norm by hybridising FPS/RPG genres. It was inspired by the gameplay of previous FPS/RPG 90’s games Ultima Underworld (1992) and System Shock (1994) by Looking Glass. (Spector, 2000). However, Spector also states he wanted to build upon the foundation laid by these games. He goes on to say his influence for the setting of the game came from his research into millennial conspiracies and his wife’s obsession with the X-Files. (2000). The game world of Deus Ex acts as a basis for the innovative success of its emergent gameplay. Without a lively game world gameplay choices would feel uninspiring. -

Session Rooms / Salles De Conférences 12 Dec / Déc 13

SESSION ROOMS / SALLES DE CONFÉRENCES 12 DEC / DÉC ND ND 9 - 9:30 AM OPENING CEREMONY with Vibe Avenue ROOM 210H - 2 FLOOR / CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST in the Business Lounge ROOM 210D - 2 FLOOR (for Business Pass holders only) Sponsored by COGECO PEER 1 9:30 - 10:30 AM OPENING KEYNOTE Fireside Chat: StudioMDHR and the Cuphead Craze by Chad Moldenhauer, Jared Moldenhauer and Maja Moldenhauer - StudioMDHR, Moderated by Jason Della Rocca, Programming Chair ROOM 210H - 2ND FLOOR ND 10:30 - 11 AM COFFEE BREAK (30 MINUTES) in the Expo Floor ROOM 210ABCDFG - 2 FLOOR Sponsored by WB GAMES Montreal ARTS AND ANIMATION AUDIO BUSINESS & MARKETING GAME DESIGN INDUSTRY & ADVOCACY PROD AND PROJECT PROGRAMMING & TECH. MIXED SESSIONS SPONSORED SESSIONS ROOM: 510B ROOM: 510D ROOM: 511C ROOM: 511D ROOM: 511E MANAGEMENT ROOM: 511B ROOM: 510AC ROOM: 511A 5TH FLOOR 5TH FLOOR 5TH FLOOR 5TH FLOOR 5TH FLOOR ROOM: 511F 5TH FLOOR 5TH FLOOR 5TH FLOOR 5TH FLOOR 11 AM - 12 PM Inspired world building Music theory for sound To self-publish or not to Designing and evaluating Thrive games: design Production, the Indie way: Cache coherent data: Leveling up your eSports Raphael Lacoste - Ubisoft design Vincent Gagnon - self-publish? An indie spectator experiences in recipes for empathy 3 methods for sanity and why you should care Tony broadcast: creating revolutionary Ubisoft survival guide to eSports Pejman games and beyond Heidi success Samantha Cook - Albrecht - Riot Games interactive streams for spectators self-publishing in the Mirza-Babaei - Execution McDonald - iThrive Games Artifact 5, Tanya Short - Jacob Navok - Genvid mobile F2P world David P. -

Comics and Videogames

14 Creating Lara Croft The meaning of the comic books for the Tomb Raider franchise Josefa Much Since the creation of Lara Croft in 1996, it seems impossible to imagine the game industry without her. Her pop-cultural impact certainly affected the gaming industry, but the expansion of her character into a whole franchise has also immortalized her through action figures, cosplay, music videos, and appearances in many other media. If you take a closer look at the franchise, you will find a number of different videogames for different gaming platforms as well as three action films, six novels, and many comic books. Shortly after the release of the very firstTomb Raider game in 1996, the comic book pub- lisher Top Cow released a crossover with their own heroine Sara Pezzini aka Witchblade and Lara Croft: Tomb Raider/ Witchblade (Turner 1997, 1998). The Witchblade comic books were one of Top Cow’s most prominent series. As a result, something very interesting happened: Lara Croft was introduced into a new universe beyond her own games, and thus into a new storyworld. She became part of the Top Cow universe as both franchises collided. Two years later, the Tomb Raider received her own stand- alone comic book series. It not only focused on her adventures, but also on her personal thoughts and approach, introducing different characters and friends of hers. Later on, this would be used to create new crossovers with different Top Cow characters (e.g., Dark Crossing [Holland and Turner 2000a, 2000b]; Endgame [Rieber and Green 2003a, 2003b, 2003c; Silvestri and Tan 2003; Turner 2002c]; the Magdalena crossover [Bonny and Basaldua 2004a, 2004b, 2004c]; the Fathom/ Witchblade/ Tomb Raider crossover [Turner 2000, 2002a, 2002b]). -

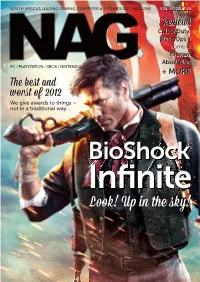

Bioshock Infinite

SOUTH AFRICA’S LEADING GAMING, COMPUTER & TECHNOLOGY MAGAZINE VOL 15 ISSUE 10 Reviews Call of Duty: Black Ops II ZombiU Hitman: Absolution PC / PLAYSTATION / XBOX / NINTENDO + MORE The best and wors t of 2012 We give awards to things – not in a traditional way… BioShock Infi nite Loo k! Up in the sky! Editor Michael “RedTide“ James [email protected] Contents Features Assistant editor 24 THE BEST AND WORST OF 2012 Geoff “GeometriX“ Burrows Regulars We like to think we’re totally non-conformist, 8 Ed’s Note maaaaan. Screw the corporations. Maaaaan, etc. So Staff writer 10 Inbox when we do a “Best of [Year X]” list, we like to do it Dane “Barkskin “ Remendes our way. Here are the best, the worst, the weirdest 14 Bytes and, most importantly, the most memorable of all our Contributing editor 41 home_coded gaming experiences in 2012. Here’s to 2013 being an Lauren “Guardi3n “ Das Neves 62 Everything else equally memorable year in gaming! Technical writer Neo “ShockG“ Sibeko Opinion 34 BIOSHOCK INFINITE International correspondent How do you take one of the most infl uential, most Miktar “Miktar” Dracon 14 I, Gamer evocative experiences of this generation and make 16 The Game Stalker it even more so? You take to the skies, of course. Contributors 18 The Indie Investigator Miktar’s played a few hours of Irrational’s BioShock Rodain “Nandrew” Joubert 20 Miktar’s Meanderings Infi nite, and it’s left him breathless – but fi lled with Walt “Shryke” Pretorius 67 Hardwired beautiful, descriptive words. Go read them. Miklós “Mikit0707 “ Szecsei 82 Game Over Pippa -

006NAG June 2013

SOUTH AFRICA’S LEADING GAMING, COMPUTER & TECHNOLOGY MAGAZINE Vol. 16 Issue THREE CALL OF DUTY: GHOSTS PC / PLAYSTATION / XBOX / NINTENDO We go to Los Angeles to stroke some beards and fi ddle PLEASE TRY TO with man stuff UNDERSTAND Intel IDF 2013 Beijing: 4th generation core technology We insert our probes deep into the soft meaty insides of 2K’s latest alien mystery Editor Michael “RedTide“ James [email protected] Contents Assistant editor Geoff “GeometriX“ Burrows Staff writer Dane “Barkskin “ Remendes Features Contributing editor Lauren “Guardi3n “ Das Neves 30 CALL OF DUTY:DU GHOSTS ComeCome on, you had to knowkno this was bound to happen. Technical writer 2013’s2013’s Call of Dutyy wantswant you to pay close attention Neo “ShockG“ Sibeko RegularsRegulars to its new enengine,gine, new sstoryline,t new player-triggered events andand new dogdog companion,com all so that when the International correspondent 1010 Ed’sEd’s NoteNote gamegame releases you’reyou’re readyrea for a bit of expectedly Miktar “Miktar” Dracon 12 InboxInbox familiar,familiar, ggoodood ol’ COD. 16 BytesBytes Contributors 53 home_codedhome_coded Rodain “Nandrew” Joubert Walt “Shryke” Pretorius 62 EverythingEverything elseelse 44 THE BUREAU:BUREA Miklós “Mikit0707 “ Szecsei XCOMXCOM DECLASSIFIEDDECLASS Pippa “UnexpectedGirl” Tshabalala It’sIt’s baaaaack! 2K2K Marin’sMarin’s XCOM has fl ipped itself on its Tarryn “Azimuth “ Van Der Byl head, adopting a diff erenteren approach in turning XCOM Adam “Madman” Liebman OpinionOpinion intointo a more hands-on, acaction-oriented alien-bashing Wesley “Cataclysm” Fick 16 I, GamGamerer experience with enoughenough tactical depth to satisfy anyoneanyone lookinlookingg for a bit more intelligence in their 1188 ThThee GaGameme SStalkertalker Art director shooters. -

42Pcpowerplay

42 PCPOWERPLAY THE MASTER OF IMMERSION Warren Spector talks choice and consequence, why playstyle matters, and the future of the PC’s most captivating sub-genre ORIGIN, LooKING GlASS, f I pulled out a gun in this restaurant, Spector holsters his weapon. it would be the biggest moment of “We’re the only medium that asks AND IoN STORM. ULTIMA “I my life,” says Warren Spector. We’re questions. That is the fundamental UNDERWORLD, SYSTEM having lunch on Melbourne’s Southbank difference between games and everything Promenade, overlooking the Yarra River. else. Not to do that is a sin.” SHOCK, AND DEUS EX. His hand appears from his pocket, I decide it’s probably best to ask thumb and forefinger extended in the another question. THESE ARE SOME OF THE shape of a pistol. He takes aim over MOST IMPORTANT PC my shoulder at a quiet man enjoying an PUNK PHILOSOPHY equally quiet seafood platter. Talk to people at Spector’s studio, Junction DEVEloPERS, AND THEIR “That guy is going to start screaming,” Point, and they’ll describe him as the guy MOST ENTHRAllING GAMES. he says. The man doesn’t notice. who yells all the time. Spector changes targets, acquiring a “I have very little patience for fools,” THEY All BEloNG TO A FAMILY fashionable young couple sitting behind he tells me. “If I think you’re stupid, him. “Those people over there are going to you’re going to know about it. I’m a real KNOWN AS THE IMMERSIVE draw their own guns,” he calculates. jerk, honestly.” SIMULATION. -

Deus Ex Human Revolution Pc Games Download Megasync Deus Ex: Human Revolution - V1.2.633.0 +11 Trainer - Download

deus ex human revolution pc games download megasync Deus Ex: Human Revolution - v1.2.633.0 +11 Trainer - Download. Gameplay-facilitating trainer for Deus Ex: Human Revolution . This trainer may not necessarily work with your copy of the game. file type Trainer. file size 181.4 KB. last update Tuesday, October 18, 2011. Report problems with download to [email protected] In order to unpack this file after download, please enter the following password: trainer . For unpacking files we recommend using a free software - 7-Zip. Unzip the contents of the archive, run the trainer, and then the game. During the game you will be able to use the following keys: NUMPAD1 -unlimited amount of Ammo. NUMPAD2 -you do not need to reload weapons. NUMPAD + -maximum power. NUMPAD4 -single attack opponent neutralizes. NUMPAD5 -add 100 experience points (you can type a different value in the trainer) NUMPAD6 -add 1000 credits (you can type a different value in the trainer) NUMPAD7 � adding 10 points to Praxis (you can type a different value in the trainer) NUMPAD8 -running without any restrictions. NUMPAD9 -unlimited battery power. NUMPAD0 -counter to stop the passage of time while solving mini-games hack. Please Note! Trainer works only with version 1.2.633.0 of the game! Last update: Tuesday, October 18, 2011 Genre: RPG File size: 181.4 KB. Note: The cheats and tricks listed above may not necessarily work with your copy of the game. This is due to the fact that they generally work with a specific version of the game and after updating it or choosing another language they may (although do not have to) stop working or even malfunction. -

Patterns of Play: Play-Personas in User-Centred Game Development

Patterns of Play: Play-Personas in User-Centred Game Development Alessandro Canossa Anders Drachen Denmark Design School / IO Interactive Center for Computer Games Research, Strandboulevarden 47, 2100 Copenhagen Ø, IT University of Copenhagen Denmark / Rued Langgaards Vej 7, 2300 Copenhagen, Kalvebod Brygge 4, 1354 Copenhagen K, Denmark, Denmark [email protected] [email protected] /[email protected] ABSTRACT towards being put in charge of the content, to a smaller or In recent years certain trends from User-Centered design greater degree, as is evidenced by the sales figures of titles have been seeping into the practice of designing computer such as Little Big Planet [5a], Spore [7a] and The Sims 3 games. The balance of power between game designers and [9a]. players is being renegotiated in order to find a more active role for players and provide them with control in shaping Other games, such as Fallout 3 [2a], Grand theft Auto IV the experiences that games are meant to evoke. A growing [4a], The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion [8a], retain complete player agency can turn both into an increased sense of creative control but opt for open worlds and modular player immersion and potentially improve the chances of narratives to increase player’s agency. critical acclaim. There seem to be a push for games to become more This paper presents a possible solution to the challenge of democratic, the power balance between game designers and involving the user in the design of interactive entertainment players could be shifting. The dictatorship of game by adopting and adapting the "persona" framework designers, holding all the cards and slowly revealing the introduced by Alan Cooper in the field of Human Computer game at their own pace to the players, is coming to terms Interaction. -

Integrating Emergence and Progression

Integrating Emergence and Progression Joris Dormans Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences Duivendrechtsekade 36-38 1096 AH, Amsterdam, the Netherlands +31 20 595 1686 [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper investigates how structures of emergence and progression in games might be integrated. By leveraging the formalism of Machination diagrams, the shape of the mechanics that typically control progression in games are exposed. Two strategies to create mechanics that control progression but exhibit more emergent behavior by including feedback loops are presented and discussed. Keywords game design, emergence, progression, level design INTRODUCTION Games are complex rule based systems that exhibit many emergent properties on the one hand, but must deliver a well-designed, natural flowing user experience on the other. These two aspects of games, often referred to as “emergence” and “progression” respectively (Juul, 2002, 2005), are generally considered be two different ways of creating gameplay challenges. Put simply, with emergence relatively simple rules lead to much variation in gameplay, whereas with progression many predesigned challenged are ordered sequentially. According to Jesper Juul, “emergence is the primordial game structure” (Juul, 2002, 324); and is the result of the many possible outcomes made possible by the rules in board games, card games, strategy games and many action games. Games of this type can be in many different states: the displacement of a single pawn by one square in a Chess game can make a huge difference. The number of possible combinations of pieces on a Chess board is huge, yet the rules easily fit on a single page. Something similar can be said of the placements of residential zones in the simulation game SimCity (Maxis Software, 1989) or the placement of a units in the strategy game like Starcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, 1998). -

L'evoluzione Della Relazione Uroborica Fra Videogioco E Musica: Il Singolare Caso Di Transculturalità Dell'industria Videoludica Giapponese

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Economia e Gestione delle Arti e delle Attività culturali Dipartimento di Filosofia e Beni culturali Tesi di Laurea L'evoluzione della relazione uroborica fra videogioco e musica: il singolare caso di transculturalità dell'industria videoludica giapponese Relatore: Giovanni De Zorzi Correlatrice: Maria Roberta Novielli Laureando: Enrico Pittalis Numero di Matricola: 871795 Anno accademico 2018/2019 Sessione Straordinaria Ringrazio Valentina, la persona più preziosa, senza cui questo lavoro non sarebbe stato possibile. Ringrazio i miei relatori, i professori Giovanni De Zorzi e Maria Roberta Novielli, che mi hanno guidato lungo questo percorso con grande serietà. Ringrazio i miei amici per i tanti consigli, confronti e spunti di riflessione che mi hanno dato. Ringrazio il Dott. Tommaso Barbetta per avermi incoraggiato ed aiutato a trovare gli obiettivi e il Prof. Toshio Miyake per avermi suggerito dei materiali di approfondimento. Ringrazio il Prof. Marco Fedalto per avermi dato importantissimi consigli. Ringrazio i miei genitori per avermi sostenuto nelle mie scelte, anche le più stravaganti. Glossario: - Anime: termine con cui si fa riferimento alle serie televisive animate prodotte in Giappone, spesso adattamenti televisivi di romanzi brevi o manga, talvolta videogiochi. - Arcade: prestito linguistico dall’inglese, termine con cui ci si riferisce alle “Macchine da gioco”, costituita fisicamente da un videogioco posto all'interno di un cabinato di grandi dimensioni operabile a monete o gettoni, che normalmente viene posto in postazioni pubbliche come sale giochi, bar, talvolta cinema e centri commerciali. L’Etimologia è incerta, probabilmente derivante da “Arcata” facente riferimento storicamente a lunghi viali sotto i portici dei borghi, dove si trovavano le botteghe e luoghi dediti al divertimento.