Copyright by Audrey Russek 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014

Kansas History A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014 A collaboration of the Kansas Historical Foundation and the Department of History at Kansas State University A Show of Patriotism German American Farmers, Marion County, June 9, 1918. When the United States formally declared war against Onaga. There are enough patriotic citizens of the neighborhood Germany on April 6, 1917, many Americans believed that the to enforce the order and they promise to do it." Wamego mayor war involved both the battlefield in Europe and a fight against Floyd Funnell declared, "We can't hope to change the heart of disloyal German Americans at home. Zealous patriots who the Hun but we can and will change his actions and his words." considered German Americans to be enemy sympathizers, Like-minded Kansans circulated petitions to protest schools that spies, or slackers demanded proof that immigrants were “100 offered German language classes and churches that delivered percent American.” Across the country, but especially in the sermons in German, while less peaceful protestors threatened Midwest, where many German settlers had formed close- accused enemy aliens with mob violence. In 1918 in Marion knit communities, the public pressured schools, colleges, and County, home to a thriving Mennonite community, this group churches to discontinue the use of the German language. Local of German American farmers posed before their tractor and newspapers published the names of "disloyalists" and listed threshing machinery with a large American flag in an attempt their offenses: speaking German, neglecting to donate to the to prove their patriotism with a public display of loyalty. -

Hispanic Archival Collections Houston Metropolitan Research Cent

Hispanic Archival Collections People Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

Houston Chronicle Index to Mexican American Articles, 1901-1979

AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE This index of the Houston Chronicle was compiled in the Spring and summer semesters of 1986. During that period, the senior author, then a Visiting Scholar in the Mexican American Studies Center at the University of Houston, University Park, was engaged in researching the history of Mexican Americans in Houston, 1900-1980s. Though the research tool includes items extracted for just about every year between 1901 (when the Chronicle was established) and 1970 (the last year searched), its major focus is every fifth year of the Chronicle (1905, 1910, 1915, 1920, and so on). The size of the newspaper's collection (more that 1,600 reels of microfilm) and time restrictions dictated this sampling approach. Notes are incorporated into the text informing readers of specific time period not searched. For the era after 1975, use was made of the Annual Index to the Houston Post in order to find items pertinent to Mexican Americans in Houston. AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE by Arnoldo De Leon and Roberto R. Trevino INDEX THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE October 22, 1901, p. 2-5 Criminal Docket: Father Hennessey this morning paid a visit to Gregorio Cortez, the Karnes County murderer, to hear confession November 4, 1901, p. 2-3 San Antonio, November 4: Miss A. De Zavala is to release a statement maintaining that two children escaped the Alamo defeat. History holds that only a woman and her child survived the Alamo battle November 4, 1901, p. -

Felix Tijerina

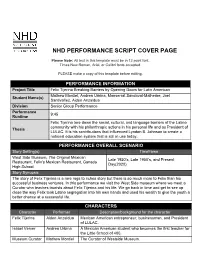

NHD PERFORMANCE SCRIPT COVER PAGE Please Note: All text in this template must be in 12 point font. Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri fonts accepted. PLEASE make a copy of this template before editing. PERFORMANCE INFORMATION Project Title Felix Tijerina Breaking Barriers by Opening Doors for Latin American Mathew Montiel, Andrea Urbina, Monserrat Sandoval-Malherbe, Joel Student Name(s) Santivañez, Aiden Anzaldua Division Senior Group Performance Performance 9:45 Runtime Felix Tijerina tore down the social, cultural, and language barriers of the Latino community with his philanthropic actions in his personal life and as President of Thesis LULAC. It is his contributions that influenced Lyndon B. Johnson to create a national education system that is still in use today. PERFORMANCE OVERALL SCENARIO Story Setting(s) Timeframe West Side Museum, The Original Mexican Late 1920’s, Late 1950’s, and Present Restaurant, Felix’s Mexican Restaurant, Ganado Day(2020) High School Story Synopsis The story of Felix Tijerina is a rare rags to riches story but there is so much more to Felix than his successful business ventures. In this performance we visit the West Side museum where we meet a Curator who teaches tourists about Felix Tijerina and his life. We go back in time and get to see up close the way Felix took Latino segregation into his own hands and used his wealth to give the youth a better chance at a successful life. CHARACTERS Character Performer Description/background for the character Felix Tijerina Aiden Anzaldua Mexican American entrepreneur, businessman, and President of LULAC. Isabel Verver Andrea Urbina A Mexican American student who becomes the first teacher for the Little School of 400. -

Building the Meat Packing Industry in South Omaha, 1883-1898

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 8-1-1989 Building the meat packing industry in South Omaha, 1883-1898 Gail Lorna DiDonato University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation DiDonato, Gail Lorna, "Building the meat packing industry in South Omaha, 1883-1898" (1989). Student Work. 1154. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/1154 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUILDING THE MEAT PACKING INDUSTRY IN SOUTH OMAHA, 1883-1898 A Thesis Presented to the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA AT OMAHA by Gail Lorna DiDonato August, 1989 UMI Number: EP73394 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertaffan PWWfeMng UMI EP73394 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 THESIS ACCEPTANCE Acceptance for the faculty of the Graduate College, University of Nebraska, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts, University of Nebraska at Omaha. -

There Are Eight Million Stories in My Albums. This Is One of Them... Coon Chicken Inn Was an American Chain of Four Restaurants

There are eight million stories in my albums. This is one of them... Coon Chicken Inn was an American chain of four restaurants founded by Maxon Lester Graham and Adelaide Burt in 1925, which prospered until the late 1950s. The restaurant's name uses an ethnic slur, and the trademarks and entrances of the restaurants were designed to look like a smiling blackface caricature of an African-American porter. The smiling capped porter head also appeared on menus, dishes, and promotional items. African Americans opposed this blatant display of racism. In 1930, the Seattle branch of the National Association for the Advancement for Colored People (NAACP) and Seattle’s African American newspaper The Northwest Enterprise protested the opening of the local Coon Chicken Inn by threatening Graham with a lawsuit for libel and defamation of race. In response, Graham agreed to change the style of advertising by removing the word ‘Coon’ from the restaurant’s delivery car, repainting the ‘Coon head’ entrance to the restaurant, and canceling an order of 1,000 automobile tire covers. This small stride, however, was not enough to fully erase the image of the caricature from Seattle. Graham violated his agreement with the NAACP but managed to evade the lawsuit by changing the color of the Coon logo from black to blue. The first Coon Chicken Inn was opened in suburban Salt Lake City, Utah in 1925. In 1929, another restaurant was opened in then-suburban Lake City, Seattle, and a third was opened in the Hollywood District of Portland, Oregon, in 1931. A fourth location was advertised but never opened in Spokane, Washington. -

On Whiteness As Property and Racial Performance As Political Speech

PASSING AND TRESPASSING IN THE ACADEMY: ON WHITENESS AS PROPERTY AND RACIAL PERFORMANCE AS POLITICAL SPEECH Charles R. Lawrence IIl* 1. INTRODUCING OUR GRANDMOTHERS Cheryl Harris begins her canonical piece, Whiteness as Property, by in troducing her grandmother Alma. Fair skinned with straight hair and aquiline features, Alma "passes" so that she can feed herself and her two daughters. Harris speaks of Alma's daily illegal border crossing into this land reserved for whites. After a day's work, Alma returns home each evening, tired and worn, laying aside her mask and reentering herself.! "No longer immediately identifiable as 'Lula's daughter,' Alma could enter the white world, albeit on a false passport, not merely passing, but trespassing. "2 In this powerful metaphorical narrative of borders and trespass, of masking and unmasking, of leaving home and returning to reenter one self, we feel the central truths of Harris's theory. She asserts that white ness and property share the premise and conceptual nucleus of a right to exclude,3 that the rhetorical move from slave and free to black and white was central to the construction of race,4 that property rights include intan gible interests,s that their existence is a matter of legal definition, that the * Professor of Law, William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawaii. B.A. 1965, Haverford College; J.D. 1969 Yale Law School. The author thanks the William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawaii at Manoa, the UCLA Law School Critical Race Studies Program and the I, Too, am Harvard Blacktavism Conference 2014 where earlier versions of this paper were presented. -

1920 Patricia Ann Mather AB, University

THE THEATRICAL HISTORY OF WICHITA, KANSAS ' I 1872 - 1920 by Patricia Ann Mather A.B., University __of Wichita, 1945 Submitted to the Department of Speech and Drama and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Redacted Signature Instructor in charf;& Redacted Signature Sept ember, 19 50 'For tne department PREFACE In the following thesis the author has attempted to give a general,. and when deemed.essential, a specific picture of the theatre in early day Wichita. By "theatre" is meant a.11 that passed for stage entertainment in the halls and shm1 houses in the city• s infancy, principally during the 70' s and 80 1 s when the city was still very young,: up to the hey-day of the legitimate theatre which reached. its peak in the 90' s and the first ~ decade of the new century. The author has not only tried to give an over- all picture of the theatre in early day Wichita, but has attempted to show that the plays presented in the theatres of Wichita were representative of the plays and stage performances throughout the country. The years included in the research were from 1872 to 1920. There were several factors which governed the choice of these dates. First, in 1872 the city was incorporated, and in that year the first edition of the Wichita Eagle was printed. Second, after 1920 a great change began taking place in the-theatre. There were various reasons for this change. -

A QED Framework for Nonlinear and Singular Optics

A QED framework for nonlinear and singular optics A thesis submitted by: Matt M. Coles as part of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the School of Chemistry University of East Anglia Norwich NR4 7TJ © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. The research in this thesis has not been submitted previously for a degree at this or any other university. Except where explicitly mentioned, the work is of my own. M. M. Coles January 2014 Abstract The theory of quantum electrodynamics is employed in the description of linear and nonlinear optical effects. We study the effects of using a two energy level approximation in simplifying expressions obtained from perturbation theory, equivalent to truncating the completeness relation. However, applying a two-level model with a lack of regard for its domain of validity may deliver misleading results. A new theorem on the expectation values of analytical operator functions imposes additional constraints on any atom or molecule modelled as a two-level system. We introduce measures designed to indicate occasions when the two-level approximation may be valid. Analysis of the optical angular momentum operator delivers a division into spin and orbital parts satisfying electric-magnetic democracy, and determine a new compartmentalisation of the optical angular momentum. An analysis is performed on the recently rediscovered optical chirality, and its corresponding flux, delivering results proportional to the helicity and spin angular momentum in monochromatic beams. -

Investigation of Beef Packers' Use of Alternative Marketing Arrangements

Investigation of Beef Packers’ Use of Alternative Marketing Arrangements United States Department of Agriculture Grain Inspection, Packers and Stockyards Administration Packers and Stockyards Program Western Regional Office 3950 Lewiston St., Suite 200 Aurora, CO 80011-1556 July 2014 Investigation of Beef Packers’ Use of Alternative Marketing Arrangements Executive Summary The USDA’s Grain Inspection, Packers and Stockyards Administration (GIPSA) conducted an investigation in response to complaints by participants in the cattle industry that the top four beef packers used committed supplies1 in ways that were anticompetitive. Their concern was that by using committed supplies and formula pricing, (referred to in this report as “alternative marketing arrangements” or AMAs) the cash market was less competitive resulting in lower fed cattle prices. Investigators from GIPSA’s Western Regional Office Business Practices Unit of the Packers and Stockyards Program (P&SP) conducted the investigation. This report details the methods and findings of the investigation, the purpose of which was to determine if the use of AMAs violates the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 (Act). P&SP investigators conducted numerous interviews and collected written statements from cattle producers, sellers, feeders, industry organizations, and the packers. The investigation examined confidential transaction data from USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS), and confidential transaction data from the four largest beef packers and various cattle sellers. The report documents the structure of fed cattle markets and confirms that, in general, the markets are highly concentrated, especially at the regional level and with regard to negotiated cash sales. Negotiated cash market purchases made up about 39 percent of total fed cattle purchases in the United States in 2009. -

Representations of Blackface and Minstrelsy in Twenty- First Century Popular Culture

Representations of Blackface and Minstrelsy in Twenty- First Century Popular Culture Jack HARBORD School of Arts and Media University of Salford, Salford, UK Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, June 2015 Table of Contents List of Figures iii Acknowledgements vii Abstract viii Introduction 1 1. Literature Review of Minstrelsy Studies 7 2. Terminology and Key Concepts 20 3. Source Materials 27 4. Methodology 39 5. Showing Blackface 5.1. Introduction 58 5. 2. Change the Joke: Blackface in Satire, Parody, and Irony 59 5. 3. Killing Blackface: Violence, Death, and Injury 95 5. 4. Showing Process: Burnt Cork Ritual, Application, and Removal 106 5. 5. Framing Blackface: Mise-en-Abyme and Critical Distance 134 5. 6. When Private goes Public: Blackface in Social Contexts 144 6. Talking Blackface 6. 1. Introduction 158 6. 2. The Discourse of Blackface Equivalency 161 6. 3. A Case Study in Blackface Equivalency: Iggy Azalea 187 6. 4. Blackface Equivalency in Non-African American Cultural Contexts 194 6. 5. Minstrel Show Rap: Three Case Studies 207 i Conclusions: Findings in Contemporary Context 230 References 242 ii List of Figures Figure 1 – Downey Jr. playing Lazarus playing Osiris 30 Figure 2 – Blackface characters in Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show 64 Figure 3 – Mantan: Cotton plantation/watermelon patch 64 Figure 4 – Mantan: chicken coup 64 Figure 5 – Pierre Delacroix surrounded by African American caricature memorabilia 65 Figure 6 – Silverman and Eugene on return to café in ‘Face -

Hospitality Soap Wrappers Collection 2015.290

Hospitality soap wrappers collection 2015.290 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Hospitality soap wrappers collection 2015.290 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Inventory ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 By state .......................................................................................................................................................