Investigation of Beef Packers' Use of Alternative Marketing Arrangements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building the Meat Packing Industry in South Omaha, 1883-1898

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 8-1-1989 Building the meat packing industry in South Omaha, 1883-1898 Gail Lorna DiDonato University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation DiDonato, Gail Lorna, "Building the meat packing industry in South Omaha, 1883-1898" (1989). Student Work. 1154. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/1154 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUILDING THE MEAT PACKING INDUSTRY IN SOUTH OMAHA, 1883-1898 A Thesis Presented to the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA AT OMAHA by Gail Lorna DiDonato August, 1989 UMI Number: EP73394 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertaffan PWWfeMng UMI EP73394 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 THESIS ACCEPTANCE Acceptance for the faculty of the Graduate College, University of Nebraska, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts, University of Nebraska at Omaha. -

Hospitality Soap Wrappers Collection 2015.290

Hospitality soap wrappers collection 2015.290 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Hospitality soap wrappers collection 2015.290 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Inventory ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 By state ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Armour's Root Beer

48 Fall 2003 Bottles and Extras stoneware root beer mugs. Their stone- ware root beer mugs held 12 ounces and ARMOUR’S were made by the Sherwood Brothers Pottery in New Brighton, Pennsylvania. Their root beer dispensers were large VERIBEST ceramic containers shaped like barrels. They were imprinted with the slogan: ROOT BEER Armour’s Veribest Root Beer. These dispensers were made by the American Standard Plumbing Supply Company in By Donald Yates from the war. Toledo, Ohio. High quality. The entrepreneur of our story was Philip Originally the Armour Company owned We can start with a quick quiz – How Danforth Armour. Philip was born in 1833 14 acres of the Chicago Stockyards, many of you remember Armour Star Hot on the Armour Family Farm having railroad lines and Dogs? Everybody should, unless you just in upstate New York. I won- refrigerated rail cars, fell off the turnip truck. Or you could have der if they raised cattle on painted with the been a vegetarian, and pretended that hot the farm? He was nineteen promotion: “We Feed the dogs don’t exist! when he headed west for the World.” One of Armour’s Okay, now let's test the other half of California gold rush. By age marketing promotions was your brain. How many of you remember 24, he had saved eight a recommendation that Armour’s Veribest Rootbeer? thousand dollars. ministers would improve If you have heard our lecture on Root Armour started a grain their preaching if they Beer, you will remember that hot dogs and business in Chicago during increased their consump- root beer are American inventions the Civil War. -

Board of Review; Holdings, Opinions and Reviews, Volume VI

Judge Advocate General's Department Holdings, Opinions and ReviftB Voluae VI including CM 202213 to CK 202976 (1934-1935) LA J N y Office of The Judge Advocate General Washington: 1944 01947 CONI'EN'l'S OF '1'0WME VI Cll No. Accused rate Page 202213 Uallon 12 Sep 1934 1 202225 Leach, Staples 15 Aug 1934 11 202243 Ysabel 27 Aug 1934 15 202250 De Ramos 15 Sep 1934 17 202253 Dosher 10 Nov 1934 23 202290 Lowr1 2 Oct 1934 67 202359 Turner 19 Nov 1934 ~ 202366 Fox 8 Oct 1934 129 202479 &.bbington 3 NOT 1934 157 202482 White 5 Nov 1934 165 202601 Sperti 10 Apr 1935 171 202720 Clem 14 Jan 1935 251 202770 Coole7 13 May 1935 259 202782 Roberts 23 Jan 1935 291 202819 Rogers 6 May 1935 303 202846 Shirley 25 liar 1935 337 202849 :Mix 4 Feb 1935 363 202861 Norbeck 4 Feb 1935 369 202928 Cooley 6 liar 1935 371 202940 Riggs 15 Feb 1935 379 202951 Wyatt 14 liar 1935 385 202976 Baker, Krueger, Johnson 2 Mar 1935 389 (1) WAR DEPARTMENT In the office of The Judge Advocate General Washington, D.C. Board of ReTi ew CM 202213 SEP 12 l~.34 UNITED STATES ) UNITED STJ.T&S MILITARY ACADEMY ) v. ) Trial by o.c.M., convened ) at West Point, New York, Private WRRAY E. MALLON ) J'U.ly 10, 1934. Diahono:re.ble (6712062), Dl!XL (U.S.M.A..), ) discharge and confinement for Field Music Detachment. ) three (3) months. West Point, ) New York. REVIEW by the BOA.RD OF REVIEW TtJRNBULL, KING and HA.LL, Judge Advocates. -

Reshaping the U.S. Cattle Industry: Producers and Packers, 1914–1933

Reshaping the U.S. cattle industry: Producers and packers, 1914–1933 by Daniel T. Gresham B.A., Colorado State University, 2006 M.A., Kansas State University, 2014 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract In 1914 the stockmen of the American West launched what they referred to as the “war on the packers.” Desiring more than rhetoric, stockmen donated their own money to finance a producer-led investigation of the big meat packer’s economic power. That investigation ultimately led to a Federal Trade Commission bombshell report that indicted the packers for attempting to control the global food supply, served them a crippling consent decree, and ended with the Packers and Stockyards Act in 1921. Perennial conflict is historians’ standard narrative of the relationship between producers and packers. However, from 1922 to 1933, producers such as John Kendrick, Dan Casement, and O. M. Plummer, cooperated with Thomas E. Wilson and other big packers along associational lines and looked to packers for industry leadership. Although contemporary producers and packers applauded their newfound cooperative attitudes, producers never fully trusted the packers, making this a tenuous cooperation. The political philosophy of associationalism helped legitimize big packer leadership of the industry. Producers’ acceptance of packer leadership is evident in their shared effort to reform the practices of meat retailers, how producers generally supported packer policies, and how they worked through the Federal Farm Board to eliminate middlemen. The packers also created a campaign for increased consumer consumption of meat and cast vegetarians as their common enemy as a way of unifying the livestock industry. -

The Packers and Stockyards Act, 1921

University of Arkansas ∙ System Division of Agriculture [email protected] ∙ (479) 575-7646 An Agricultural Law Research Article The Packers and Stockyards Act, 1921 by Thomas J. Flavin Originally published in GEORGE WASHINGTON LAW REVIEW 26 GEO. WASH. L. REV. 161 (1958) www.NationalAgLawCenter.org THE PACKERS AND STOCKYARDS ACT, 1921 Thomas ]. Flavin· I. INTRODUCTION Current legislative proposals to transfer the regulation of the trade practices of meatpackers in whole or in part from the Secretary of Agriculture to the Federal Trade Commission have brought the Packers and Stockyards Act1 to renewed public attention.2 The act constitutes one of the early major entries of the Federal Government into the regulation of private industry and is antedated in this respect only by the establishment of the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1887 and of the Federal Trade Commission in 1914. For years prior to the enactment of the act in 1921, the largest meat packing companies had been charged with conspiring to control the purchases of livestock, the preparation of meat and meat products and the distribution thereof in this country and abroad. In 1917 President Wilson directed the Federal Trade Commission to investi gate the facts relating to the meatpacking industry and the Commis sion issued a report in July 1918 which concluded that the "Big Five" (Swift, Armour, Cudahy, \\Tilson and Morris) controlled the market in which they bought their supplies and the market in which they sold their products and were reaching for mastery of the trade in meat substitutes such as cheese, eggs, etc., as well. The report pointed out that the monopolistic position of the "Big Five" was based primarily upon their ownership or control of stockyards and essential facilities for the distribution of perishable foods and that control of stockyards carried with it domin:mce over commission finns, dealers, cattle-loan banks, trade publications, etc.3 *Judicial Officer, United States Department of Agriculture. -

Dissertation Full Draft

The Alchemy of Capital: Industrial Waste and the Chemicalization of United States Agriculture By Adam M. Romero A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nathan F. Sayre, Chair Professor Richard A. Walker Professor Robin L. Einhorn Professor Garrison Sposito Spring 2015 The Alchemy of Capital: Industrial Waste and the Chemicalization of United States Agriculture © 2015 Adam M. Romero Abstract The Alchemy of Capital: Industrial Waste and the Chemicalization of United States Agriculture by Adam M. Romero Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Nathan F. Sayre, Chair Along with mechanization and scientific plant breeding, modern forms of industrial agriculture are premised on the use of synthetic chemicals to sustain yield, irrigate fields, decrease erosion, and provide defense against pests and disease. Chemicalized agriculture has its origins in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as the presence of industrially produced chemicals became available on domestic and international markets, as crop production specialized, and as scientists, farmers, and policy makers turned to chemicals to “fix” fertility, pest, and labor issues. While the use of agricultural chemicals has created the conditions for astonishing yields, their generalized use has also resulted in the pollution and degradation of ecosystems, harmful effects on consumers and farm workers, and large greenhouse gas emissions. This dissertation investigates the relationships between the late 19th and early 20th century US mining, chemical, and petroleum refining industries, their waste byproducts, and the promotion and naturalization of economic poisons in US agriculture. -

Union Stock Yards Tour for Students of the Nebraska College of Agriculture Union Stock Yards Company

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraskiana: Resources and Materials on the 37th Nebraskiana Publications State 2-13-1917 Union Stock Yards Tour for Students of the Nebraska College of Agriculture Union Stock Yards Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebraskianapubs Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Agribusiness Commons, Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, Animal Studies Commons, and the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraskiana: Resources and Materials on the 37th State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraskiana Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ~ IfIlm _1m! ~""""'llltmllllI ... nlllllWallUllll"UIIUlIlOKmUIIlIIllItAIUUIIIIUll&III1IUIIUIIIDltIIUUUllWNl_IIIU"ltlUUIIlllfttlHIU8IUIIIIIIWI............wtUI_It~ ~""I"""'nUn""" •. u""""........ ~;I:lf ...~l l lItn.tHtttI"""'"IIH,..... .. IIIII ...m~'""m nlftlloNttHUM' fttl tN'tn ' .....nn'H""'MIH ' ......... IIIU ....IMttIU I "'-6- ~. - II , Gr:e~ngs II Students of the UniversiW II of the State of Nebraska II ~ Ii ~ C.of A. Ii I Ii ! II I ='" II II !)nion Stock Yards Co. II Omaha, Nebraska II Tuesday, February 13. 1917 n - II ~IIIIIIIUlllllllllllllllllHllIllllllIIUUIUIIIUlllllullllllmwllUulullWIIlIIi 111111111'1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII'I'IUIIIIIIIIIIII.IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII11111111'11111111 -

Foreign Claim Settlement Commission of the United States Cuban Claims

Foreign Claim Settlement Commission of the United States Cuban Claims Program Certified Claimant List Claim Decision Amount of Loss Number Number Name of Claimant Type of Loss Type of Loss Detail Location of Property Certified CU-2578 4122 Cuban Electric Company Corporate Assets 267,568,413.62 CU-2622 3578 North American Sugar Industries, Inc. Corporate Assets 97,373,414.72 CU-2619 6049 MOA Bay Mining Company Improved Real Property Oriente, Cuba 88,349,000.00 CU-2776 3824 United Fruit Sugar Company Improved Real Property Havana, Cuba 85,100,147.09 CU-0665 5969 West Indies Sugar Corp. Corporate Assets Oriente, Cuba 84,880,957.55 CU-2445 3969 American Sugar Company Corporate Assets Camaguey, Cuba 81,011,240.24 CU-2615 5013 ITT as Trustee Corporate Assets 80,002,794.14 CU-0938 3838 Exxon Corporation Corporate Assets Havana, Cuba 71,611,002.90 CU-2500 6066 The Francisco Sugar Company Corporate Assets 52,643,438.37 Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide, CU-2-001 CU-2-001 Inc Corporate Assets Havana, Cuba 51,128,926.95 International Telephone and Telegraph CU-2615 5013 Co Corporate Assets 50,676,963.88 CU-1331 4546 Texaco, Inc. Corporate Assets Havana, Cuba 50,081,109.67 CU-2525 6020 Manati Sugar Company Corporate Assets 48,587,847.82 CU-2156 6034 Bangor Punta Corporation Securities Other Cuban Entities 39,078,904.64 CU-2624 6247 Nicaro Nickel Company Corporate Assets 33,014,082.52 CU-1743 6818 The Coca-Cola Company Improved Real Property Havana, Cuba 27,526,239.03 CU-2355 6217 Lone Star Cement Company Corporate Assets Havana, Cuba 24,881,287.00 CU-1850 6817 The New Tuinucu Sugar Company Improved Real Property Las Villas, Cuba 23,336,079.64 CU-0730 4547 Colgate-Palmolive Corporate Assets 14,507,935.04 CU-2526 6057 Braga Brothers, Inc. -

Meatpackers Strike of 1948

1948 Meatpackers Strike by William Lanoue Many were home from war and wanted more than ever to live a long full life. Others had worked long days and nights dur - ing the war to feed the Surveillance photos taken from the Exchange Building show the National Guard troops overseas as well as gathered at the center of Concord Street at the height of the 1948 meatpackers Americans on the home strike. DCHS Collections. front. Some had migrated to the cities from farms and small towns looking for Setting the Stage work. They were raising children and trying to hold bur - Less than three years after the defeat of Nazi geoning families together in the face of a housing short - Germany and Japan, America was already a far different age, fears of inflation and the increasing drumbeat warn - place. Through all but the last few months of the war ing of a new foreign enemy with sympathizers and President Franklin D. Roosevelt had led the United agents in our midst. There were those who wanted States. In fact he was the only president many higher wages now, others more concerned with pen - Americans had ever known. Roosevelt had been elected sions and health care benefits, and still others dedicat - to an unprecedented fourth term in November 1944 with ed to achieving social and political change, sometimes a little known former haberdasher from Missouri on the of radical proportions. ticket. It is hard to argue that Harry S Truman added They lived in Chicago, Kansas City, Omaha -- and much to the campaign, but in April 1945 the former South St. -

October Term, 1946

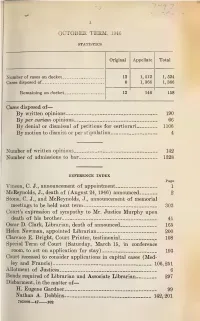

— — ru I OCTOBER TERM, 1946 STATISTICS Original Appellate Total Number of cases on docket 12 1, 512 1, 524 Cases disposed of _______ 0 1, 366 1,366 Remaining on docket __ 12 146 158 Cases disposed of By written opinions 190 By per curiam opinions 66 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 1106 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation 4 Number of written opinions 142 Number of admissions to bar 1328 REFERENCE INDEX Page Vinson, C. J., announcement of appointment 1 McReynolds, J., death of (August 24, 1946) announced 2 Stone, C. J., and McReynolds, J., announcement of memorial meetings to be held next term 303 Court's expression of sympathy to Mr. Justice Murphy upon death of his brother 41 Oscar D. Clark, Librarian, death of announced 165 Helen Newman, appointed Librarian 200 Clarence E. Bright, Court Printer, testimonial 108 Special Term of Court (Saturday, March 15, in conference room, to act on application for stay) 193 Court recessed to consider applications in capital cases (Med- ley and Francis) 106,251 Allotment of Justices 6 Bonds required of Librarian and Associate Librarian 297 Disbarment, in the matter of H. Eugene Gardner 99 Nathan A. Dobbins 142,201 705009—47 102 6 II Continued Disbarment , in the matter of— Page Leonard Eriksson 201, 260 Hulon Capshaw 260,291 Kules of Supreme Court—Rule 2 amended 71 Rules of Civil Procedure—amendments transmitted to Attor- ney General to be reported to Congress 118 Bankruptcy—amendments to general orders and forms 303 Attorney, change of name 212 Counsel appointed (Nos. -

1944 Journal

— — OCTOBER TERM, 1944 STATISTICS Original Appellate Total Number of cases on docket 11 1,382 1,393 0 1,249 1, 249 Remaining on docket . _ 11 133 144 Cases disposed of By written opinions 199 By per curiam opinions 75 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 971 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation 4 Number of written opinions 156 Number of admissions to bar (114 admitted May 21) 1, 200 REFERENCE INDEX President Roosevelt, Court recessed (Saturday session) to attend inauguration of 14S Sutherland, J., resolutions of the Bar presented by George Wharton Pepper 100 Clarke, J., death of (March 22, 1945) announced 198 Court convened at 10 : 30 June 18—adjourned to attend Joint Session of Congress in honor of General Eisenhower and re- convened at 2 : 30. Bonds of Clerk approved 119 Disbarment, etc., In the matter of Hulon Capshaw (committee appointed) 51, 167 J. Whitla Stinson (resignation) 239 Rules of Criminal Procedure prescribed and ordered trans- mitted to Attorney General with request that they be reported to Congress 119 Rules of Criminal Procedure made applicable to appeals by United States under Criminal Appeals Act 12.1 Comisel appointed (Nos. 64, 102, 212, 259, 825) 6, 163, 284 Opinions amended (Nos. 410, 371, 296, 431, 953, 699, 470 and 815) 176, 218, 242, 254, 276, 284, 291 597362—45 102 ir Page Judgments affirmed by equally divided court (Nos. 192, 55) 132, 193 Judgment affirmed on ground that findings (of I. C. C.) are sufficient to support the order, and the evidence is sufficient to support the findings (No.