A Changing Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

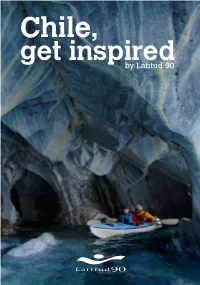

Latitud 90 Get Inspired.Pdf

Dear reader, To Latitud 90, travelling is a learning experience that transforms people; it is because of this that we developed this information guide about inspiring Chile, to give you the chance to encounter the places, people and traditions in most encompassing and comfortable way, while always maintaining care for the environment. Chile offers a lot do and this catalogue serves as a guide to inform you about exciting, adventurous, unique, cultural and entertaining activities to do around this beautiful country, to show the most diverse and unique Chile, its contrasts, the fascinating and it’s remoteness. Due to the fact that Chile is a country known for its long coastline of approximately 4300 km, there are some extremely varying climates, landscapes, cultures and natures to explore in the country and very different geographical parts of the country; North, Center, South, Patagonia and Islands. Furthermore, there is also Wine Routes all around the country, plus a small chapter about Chilean festivities. Moreover, you will find the most important general information about Chile, and tips for travellers to make your visit Please enjoy reading further and get inspired with this beautiful country… The Great North The far north of Chile shares the border with Peru and Bolivia, and it’s known for being the driest desert in the world. Covering an area of 181.300 square kilometers, the Atacama Desert enclose to the East by the main chain of the Andes Mountain, while to the west lies a secondary mountain range called Cordillera de la Costa, this is a natural wall between the central part of the continent and the Pacific Ocean; large Volcanoes dominate the landscape some of them have been inactive since many years while some still present volcanic activity. -

New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005-2015)

New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005-2015) Paul Rumney Merchant St John’s College August 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005 – 2015) Paul Rumney Merchant This thesis explores the potential of domestic space to act as the ground for new forms of community and sociability in Argentine and Chilean films from the early twenty-first century. It thus tracks a shift in the political treatment of the home in Southern Cone cinema, away from allegorical affirmations of the family, and towards a reflection on film’s ability to both delineate and disrupt lived spaces. In the works examined, the displacement of attention from human subjects to the material environment defamiliarises the domestic sphere and complicates its relation to the nation. The house thus does not act as ‘a body of images that give mankind proofs or illusions of stability’ (Bachelard), but rather as a medium through which identities are challenged and reformed. This anxiety about domestic space demands, I argue, a renewal of the deconstructive frameworks often deployed in studies of Latin American culture (Moreiras, Williams). The thesis turns to new materialist theories, among others, as a supplement to deconstructive thinking, and argues that theorisations of cinema’s political agency must be informed by social, economic and urban histories. The prominence of suburban settings moreover encourages a nuancing of the ontological links often invoked between cinema, the house, and the city. The first section of the thesis rethinks two concepts closely linked to the home: memory and modernity. -

M U R a L I S M Identity & Revolution January 30 - February 29, 2020

M U R A L I S M Identity & Revolution January 30 - February 29, 2020 1.XXX Tina Modotti XXX Diego Rivera Mural, "The World Today and Tomorrow", Palacio Nacional, Mexico City 1929-1935 Gelatin Silver Print 7 3/8 x 9 1/2 in. n.s (Inv# 73859) 2.XXX Tina Modotti XXX "Sickle, Bandolier & Guitar" ca. 1927 Platinum print 6 7/8 in. x 8 3/4 in. 5/30 Signed, titled and dated on recto and verso (Inv# 64908) 3.XXX Edward Weston XXX Tina Reciting 1926 Gelatin silver print, printed later 9 1/2 x 7 1/4 in. Printed by Cole Weston (Inv# 32799) 4.XXX Florence Arquin XXX Frida Kahlo with Corset Painted with Fetus and Hammer & Sickle. 1951 Gelatin silver print 10 x 8 in. n.s (Inv# 60897) 5.XXX Lucienne Bloch XXX Frida in Front of Proletarian Unity from the mural "Portrait of America" for the New Workers School, NY 1933 Gelatin Silver Print 11 1/2 x 7 1/2 in. Signed in pencil on recto (Inv# 76522) 6.XXX Anonymous XXX Mural by David Alfaro Siqueiros, De Porfirismo a la Revolucion (From the Dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz to the Revolution) Chapultepec Castle, Chapultepec Park, Mexico City 1944 Gelatin silver print 8 x 10 in. Labeled on verso (Inv# 60001) 7.XXX Guillermo Zamora XXX David Alfaro Siqueiros 1946 Gelatin silver print 13 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. n.s (Inv# 100769) 8.XXX Héctor García XXX José Clemente Orozco 1945 Gelatin silver print, printed 1996 14 x 11 in. -

The Street Art Culture of Chile and Its Power in Art Education

Culture-Language-Media Degree of Master of Arts in Upper Secondary Education 15 Credits; Advanced Level “We Really Are Not Artists, We Are Military. We Are Soldiers” The Street Art Culture of Chile and its Power in Art Education “Vi är inte konstnärer, vi är militärer. Vi är sodlater” Gatukonstkulturen i Chile och dess påverkan på bildundervisning Granlund, Magdalena Silén, Maria Master of Art in Secondary Education: 300 Credits. Examiner: Edström, Ann-Mari. Opposition Seminar: 31/05/2018. Supervisor: Mars, Annette. Foreword We would like to give a big thanks to all those whom have helped made this thesis possible: to all the people we have been interviewing and that have been showing us the streets of Santiago and Valparaiso. To Kajsa, Micke and Robbin for making sure we met the right people while conducting this study. To Annette Mars for all the guidance prior- and during the conducting of this thesis. To Mauricio Veliz Campos for all the support we were given during the minor field studies scholarship application, as well as during our time in Santiago. To Vinboxgruppis for your constant support during the last five years. And last but not least to SIDA, for the trust and financial support. Thank you! This thesis is written during the spring of 2018. We, the writers behind this thesis, have both come up with the purpose, research questions, method, interview guide, as well as been taking visual street notes together. 2 Abstract This thesis describes the street art culture of Chile and its power in art education. The thesis highlights the didactic questions what, how and why. -

1 El Museo Nacional De Bellas Artes De Santiago

UNIVERSUM • Vol. 31 • Nº 1 • 2016 • Universidad de Talca Te National Museum of Fine Arts of Santiago and its publications (1922-2009) Albert Ferrer Orts – Alberto Madrid Letelier Pp. 141 a 151 THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS OF SANTIAGO AND ITS PUBLICATIONS (1922-2009)1 El Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Santiago (Chile) a través de sus publicaciones: 1922-2009 Albert Ferrer Orts* Alberto Madrid Letelier** 1 Tis article forms part of the project “Ausencia de una política o política de la ausencia. Institucionalidad y desarrollo de las artes visuales en Chile 1849-1973” Fondecyt Nº 1140370, whose co-researcher is one of the authors of this publication. Tis paper was initially sent for review in Spanish, and it has been translated into English with the support of the Project FP150008, “Aumento y mejora del índice de impacto y de la internacionalización de la revista Universum por medio de la publicación de un mayor número de artículos en inglés.” Fund for publication of Scientifc Journals 2015, Scientifc Information Program, Scientifc and Technological Research National Commission (Conicyt), Chile. Este artículo fue enviado a revisión inicialmente en español y ha sido traducido al inglés gracias al Proyecto FP150008, “Aumento y mejora del índice de impacto y de la internacionalización de la revista Universum por medio de la publicación de un mayor número de artículos en inglés”. Fondo de Publicación de Revistas Científcas 2015, Programa de Información Científca, Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científca y Tecnológica (Conicyt), Chile. * Faculty of Art, Universidad de Playa Ancha de Ciencias de la Educación. Valparaíso, Chile. -

SYLLABUS GLOBAL OPPORTUNITIES CHILEAN CULTURE Universidad De Los Andes, Santiago, Chile January 2Nd – January 23Rd, 2019

SYLLABUS GLOBAL OPPORTUNITIES CHILEAN CULTURE Universidad de los Andes, Santiago, Chile January 2nd – January 23rd, 2019 COURSE: GO CHILEAN CULTURE PREREQUISITES: None CREDITS: EVALUATIONS: 2 week program: 3 US Credits / 6 ECTS Written paper and presentation about Credits chosen topic related to Chilean Culture. 3 week program: 4 US Credits / 8 ECTS Online Placement Test for Language Course. Credits Final Language Exam. TOTAL HOURS: ON CAMPUS LECTURES: CULTURAL AND ACADEMIC TRIPS AND 2 week program: 40 2 week program: 30 hours ACTIVITIES: hours 3 week program: 44 hours 2 week program: 15 hours 3 week program: 60 3 week program: 20 hours hours COURSE DESCRIPTION This course’s main objective is to give students a deep understanding of Chile’s culture through a sociological point of view from the Prehispanic Period, until today, and how it has evolved through the different migratory waves. Additionally, the course will present a general view of Chile’s current cultural scenario through different perspectives. Finally, this course includes a Language Unit, that can be either Spanish for non-Spanish speakers, or English for Spanish speakers. METHODOLOGY AND ACTIVITIES This course will include lectures by different UANDES professors and external lecturers, that will involve student interaction. Students will have to choose a topic related to Chilean Culture on which they will work through the duration of the program and will have to present it at the end of the course. They will be graded in accordance to the development of the paper, and the final presentation. Finally, the language course will include a final exam during the last week of the program. -

Embodied Absence Chilean Ar

Embodied Absence Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Carpenter Center Embodied Absence for the Visual Arts Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Oct 27, 2016–Jan 8, 2017 Works by Elías Adasme, Carmen This exhibition is co-organized Beuchat with Felipe Mujica and with DRCLAS as part of its research Johanna Unzueta, CADA (Colectivo project Conceptual Stumblings. Acciones de Arte), Francisco Copello, Exhibition and program support Luz Donoso, Juan Downey, Carlos is also provided by Harvard Leppe, Catalina Parra, Lotty University Committee on the Rosenfeld, UNAC (Unión por la Arts. The first iteration, Embodied Cultura), Cecilia Vicuña, and Raúl Absence: Ephemerality and Zurita with Cristóbal Lehyt Collectivity in Chilean Art of the 1970s (September 2015–January Guest curated by Liz Munsell, 2016), was organized by Museo Assistant Curator of Contemporary de la Solidaridad Salvador Art & Special Initiatives, Museum of Fine Allende, Santiago, Chile, with its Arts, Boston, and visiting curator, David substantial support in research Rockefeller Center for Latin American and production of works, in Studies (DRCLAS), Harvard University collaboration with DRCLAS. Embodied Absence Liz Munsell Following the U.S.-backed coup d’état in 1973,1 Chilean artists residing in Santiago and abroad created artworks that spoke to their experience of political, social, and geographic marginalization. Inside the country, they adopted the highly coded languages of conceptual art to evade censorship, exhibited work in public space in lieu of institutional support, and formed independently run galleries and artist collectives to protect their individual identities. Artists abroad staged public events and made artwork in solidarity with those at home. Their exhibitions, performances, interventions, and workshops spread awareness among international audiences and broke down isolating conditions within Chile. -

Issue 1 in This Issue

winter 2015 | volume xlvi | issue 1 in this issue Debates: Exclusiones Racismos y exclusión en América Latina: Interdisciplina, otros saberes e interseccionalidad por OLIVIA GALL Rezago epistémico y (auto)exclusión académica: Las ciencias sociales paraguayas en el concierto internacional por LUIS ORTIZ y JOSÉ GALEANO Homofobia na América Latina: Exclusão, violência e justiça por HORACIO F. SÍVORI ¿Cómo construyen crítica las comunidades indígenas? Un acercamiento a las formas de la exclusión epistémica por GLADYS TZUL TZUL The Exclusions of Gender in Neoliberal Policies and Institutionalized Feminisms by VERÓNICA SCHILD The Exclusion of (the Study of) Religion in Latin American Gender Studies by ELINA VUOLA Exclusions dans les études latino-américaines francophones au Québec par ANAHI MORALES HUDON Challenging Northern Hegemony: Toward South-South Dialogue in Latin American Studies by VASUNDHARA JAIRATH Exclusiones crónicas y ciudadanías flexibles: La soledad de los migrantes latinoamericanos en el espacio transatlántico por LILIANA SUÁREZ NAVAZ Ayotzinapa: ¿Fue el Estado? Reflexiones desde la antropología política en guerrero por ROSALVA AÍDA HERNÁNDEZ CASTILLO y MARIANA MORA President Debra Castillo Cornell University [email protected] Vice President Gilbert Joseph Yale University Past President Merilee Grindle Table of Contents Harvard University Treasurer Timothy J. Power University of Oxford 1 From the President | by DEBRA CASTILLO EXECUTIVE COUNCIL For term ending May 2015: DEBATES: EXCLUSIONES Claudio A. Fuentes, Universidad Diego -

Emelina Fuente S of Linare S, Eighty -Eight Years Old, Playing the Rabel, an Archaic Folk Violin of Chile

Emelina Fuente s of Linare s, eighty -eight years old, playing the rabel, an archaic folk violin of Chile. THE DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE, INSTITUTE FOR MUSICAL RESEARCH, UNIVERSITY OF CHILE Manuel Dannemann HISTORY The progenitor of the present Folklore Department of the In- stitute for Musical Research in the Faculty of Musical Arts and Sciences at the University of Chile in Santiago, was the Institute for Folk Music Research, established in 1943 upon the initiative of a committee composed of Eugenio Pereira, Alfonso Letelier, Vicente Salas, Carlos ~avin,Carlos Isamitt, Jorge Urrutia and Filomena Salas. Some members of this committee were also members of the Faculty of Fine Arts of that time, which encouraged this venture. Among the first activities of the newly formed Institute was the sponsorship of a series of concerts of folk and indigenous music performed by professional and amateur groups in various theatres in Santiago. During the same period the Symphony Orchestra of Chile gave concerts of Chilean art music influenced by the folk music of the country. Although these were not performances by groups of the culture in which the music originated, the music played was care- fully selected for its authenticity. The principal purpose of these concerts was to acquaint the public with the traditional music of Chile. The publication of the pamphlet, Chile? which was a guide to the afore- mentioned concerts, also served this purpose. However, its basic function was that of offering a total picture of the extant folk music. In addition, it included articles dealing with the methods used in the specialized study of folk music. -

5D717d90e4e9a8155e7e1974b

1 * Palenquero, Colombia, 1950's. 5,4 x 5,4 cm. Contacto vintage plata/gelatina !eneral Castaños # – 1% &'q., (004. )adri*. +,- 91.10.0#0 /ax- 9154 0(# www.freijofineart.com [email protected] . +exto- 0uan 1ngel 2ela *el Campo Comisaria*o 3 *iseño *el catálogo- Manuel !lez. /rei5o 6*ita- /rei5o /ine 7rt S.L. /otograf:a: /undaci;n Leo Mati' < =e la edici;n, Frei5o Fine 7rt 8.9. < =el texto, 0uan 1ngel 2ela del Campo < =e la obra, Fundaci;n Leo )ati' 4 DE M7>? A SEP+&6)@AE, 01 5 PAB9?!? )anuel !le'. Frei5o C Pentagrama es un pro3ecto que nace en un intento *e aunar una pasi;n que me Da acompa"a*o a lo largo *e to*a la vi*a, la mEsicaF 3 *e otra pasi;n que Da DecDo algo mu3 similar, la ,otogra,:a. De 9eo )ati' se Da Dabla*o mucDo, 3 se Da expuesto otro tanto, sin ir m4s le5os, @otero Di'o su primera 3 segun*a exposici;n en la galer:a que abri; )ati' all4 por los a"os 50 en @ogot4. )ati' expuso en el Mo)7, *e Gueva >orH, en el )IG79 *e )Jxico, en Italia, en Par:s, en 2ene'uela, 7ustralia, 0ap;n, por mucDos pa:ses 3 ciu*a*es se Dan po*i*o contemplar sus emotivas instant4neas. Ka Dabi*o gran*es exposiciones *e las sesiones con Fri*a LalDo, con 8iqueirosF *e sus ,otogra,i4s In*ustriales abstractas, pero 5am4s se Da DecDo ninguna acerca *e la pasi;n que sent:a 9eo por la mEsica. -

Oposición Y Democracia

Oposición 11 y democracia Soledad Loaeza Soledad Loaeza Nueva edición con nota introductoria 11 Consulta el catálogo de publicaciones del INE Cuadernos de Divulgación de la Cultura Democrática Cultura la de Divulgación de Cuadernos 1 Oposición y democracia Soledad Loaeza Oposición y democracia Soledad Loaeza Nueva edición con nota introductoria 11 Instituto Nacional Electoral Consejero Presidente Dr. Lorenzo Córdova Vianello Consejeras y Consejeros Electorales Mtra. Norma Irene De la Cruz Magaña Dr. Uuc-Kib Espadas Ancona Dra. Adriana Margarita Favela Herrera Mtro. José Martín Fernando Faz Mora Dra. Carla Astrid Humphrey Jordan Dr. Ciro Murayama Rendón Mtra. Dania Paola Ravel Cuevas Mtro. Jaime Rivera Velázquez Dr. José Roberto Ruiz Saldaña Mtra. Beatriz Claudia Zavala Pérez Secretario Ejecutivo Lic. Edmundo Jacobo Molina Titular del Órgano Interno de Control Lic. Jesús George Zamora Director Ejecutivo de Capacitación Electoral y Educación Cívica Mtro. Roberto Heycher Cardiel Soto Oposición y democracia Soledad Loaeza Primera edición, 1996 Primera edición en este formato, 2020 D.R. © 2020, Instituto Nacional Electoral Viaducto Tlalpan núm. 100, esquina Periférico Sur Col. Arenal Tepepan, 14610, México, Ciudad de México ISBN obra completa impresa: 978-607-8772-11-7 ISBN volumen impreso: 978-607-8772-22-3 ISBN obra completa electrónica: 978-607-8772-90-2 ISBN volumen electrónico: 978-607-8790-01-2 El contenido es responsabilidad de la autora y no necesariamente representa el punto de vista del INE Impreso en México/Printed in Mexico Distribución -

Informe De Autoevalu

ÍNDICE 5. EVALUACIÓN DE LAS ACTIVIDADES SUSTANTIVAS DESARROLLADAS EN EL PERIODO ENERO-DICIEMBRE 2015 1. PRESENTACIÓN GENERAL Y SÍNTESIS DE PRINCIPALES RESULTADOS 3 1.1 LAS DIVISIONES ACADÉMICAS 3 1.2 PROGRAMAS INTERDISCIPLINARIOS 5 1.3 CIDE REGIÓN CENTRO 6 1.3.1 Investigación 6 1.3.2 Docencia y formación de recursos humanos 7 1.3.3 Vinculación e impacto regional 8 1.3.4 Actividades de difusión y divulgación 8 2. PLANTA ACADÉMICA Y PROFESORES INVESTIGADORES TITULARES (PIT) 9 3. INFORME DE ACTIVIDADES SUSTANTIVAS 16 3.1 INVESTIGACIÓN 16 3.1.1 Resultados de investigación 16 3.1.2 Reconocimientos al trabajo académico de los profesores investigadores durante el 2015 23 4. AVANCE DE LOS PROYECTOS ESTRATÉGICOS DEL PROGRAMA ANUAL DE TRABAJO 2015 27 4.1 OBJETIVOS Y PROYECTOS ESTRATÉGICOS 27 4.2 FONDOS INSTITUCIONALES 34 4.3 FORMACIÓN DE RECURSOS HUMANOS DE EXCELENCIA: NUEVOS PROGRAMAS DE POSGRADO 35 4.4 USO DE TECNOLOGÍAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN Y COMUNICACIÓN (TIC) 35 4.4.1 Librería virtual y divulgación de investigaciones 36 4.4.2 Boletines semanales 36 4.4.3 Redes Sociales 37 4.5 DOCENCIA 37 4.5.1. REPORTE DE ACTIVIDADES 37 4.5.1.1. Oferta educativa y matrícula estudiantil 37 4.5.1.2. Pertenencia al Programa Nacional de Posgrados de Calidad (PNPC) 38 4.5.1.3. Reconocimientos externos obtenidos por alumnos y exalumnos 38 4.5.1.4. Acciones de respuesta a las observaciones del Comité de Evaluación Externa 39 4.5.1.5. Revisión del Reglamento de Docencia 41 4.2.1.6.