VISITING the VIDEOGAME THEME PARK Bobby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

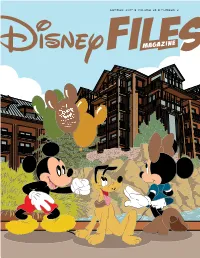

Summer 2017 • Volume 26 • Number 2

sUMMER 2017 • Volume 26 • Number 2 Welcome Home “Son, we’re moving to Oregon.” Hearing these words as a high school freshman in sunny Southern California felt – to a sensitive teenager – like cruel and unusual punishment. Save for an 8-bit Oregon Trail video game that always ended with my player dying of dysentery, I knew nothing of this “Oregon.” As proponents extolled the virtues of Oregon’s picturesque Cascade Mountains, I couldn’t help but mourn the mountains I was leaving behind: Space, Big Thunder and the Matterhorn (to say nothing of Splash, which would open just months after our move). I was determined to be miserable. But soon, like a 1990s Tom Hanks character trying to avoid falling in love with Meg Ryan, I succumbed to the allure of the Pacific Northwest. I learned to ride a lawnmower (not without incident), adopted a pygmy goat and found myself enjoying things called “hikes” (like scenic drives without the car). I rafted white water, ate pink salmon and (at legal age) acquired a taste for lemon wedges in locally produced organic beer. I became an obnoxiously proud Oregonian. So it stands to reason that, as adulthood led me back to Disney by way of Central Florida, I had a special fondness for Disney’s Wilderness Lodge. Inspired by the real grandeur of the Northwest but polished in a way that’s unmistakably Disney, it’s a place that feels perhaps less like the Oregon I knew and more like the Oregon I prefer to remember (while also being much closer to Space Mountain). -

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Disney Pinocchio Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LEVEL 3: DISNEY PINOCCHIO PDF, EPUB, EBOOK M Williams | 24 pages | 21 Feb 2012 | Pearson Education Limited | 9781408288610 | English | Harlow, United Kingdom Level 3: Disney Pinocchio PDF Book The Fairy cryptically responds that all inhabitants of the house, including herself, are dead, and that she is waiting for her coffin to arrive. Just contact our customer service department with your return request or you can initiate a return request through eBay. Reviews No reviews so far. The article or pieces of the original article was at Disney Magical World. Later, she reveals to Pinocchio that his days of puppethood are almost over, and that she will organize a celebration in his honour; but Pinocchio is convinced by his friend, Candlewick Lucignolo to go for Land of Toys Paese dei Balocchi a place who the boys don't have anything besides play. After Pinocchio find her tombstone instead of house she appears later in different forms including a giant pigeon. The main danger are the rocks. They can't hurt you, but if they grab you they'll knock you to a lower level. After finishing this last routine you beat the level. Il giorno sbagliato. By ryan level Some emoji powers don't change As the player levels Up, the emojis are available for fans to play 6 with a blue Emoji with The article or pieces of the original article was at Disney Magical World. Venduto e spedito da IBS. The order in which you should get the pages is: white, yellow, blue and red. To finish the level, you have to kill all the yellow moths. -

The Aristocats the CAST (In Order of Appearance)

=============================================================================== Disney Classic Animated Feature ARISTOCATS script (version 1.0) Disney Disclaimer: This script is taken from numerous viewings of the Feature feature and is not an official script by all means. Portions of Films: this script are copyrighted by Walt Disney Company and are used without permission. The Aristocats THE CAST (in order of appearance) Awards Opening Song Vocals Maurice Chevalier Madame Adelaide Bonfamille Hermione Baddelay Cast Edgar Roddy Maude-Roxby Duchess Eva Gabor Contents Berlioz Dean Clark Frou-frou Nancy Kulp Film Info Georges Hautecourt Charles Lane Marie Liz English Income Toulouse Gary Dubin Roquefort Sterling Holloway Napoleon Pat Buttram Info Lafayette George Lindsey Driver (milkman) Pete Renoudet Mistakes Amelia Gabble Carole Shelley Abigail Gabble Monica Evans Movie Posters Chef (le Petit Cafe): Uncle Waldo: Bill Thompson Songlyrics Scat Cat: Scatman Crothers Italian Cat: Vito Scotti English Cat: Lord Tim Hudson Russian Cat: Thurl Ravenscroft Chinese Cat: Paul Winchell Driver (postman): Mac (postman): OPENING CREDITS Walt Disney Productions presents the Aristocrats "The Aristocats" sung by Maurice Chevalier [Marie, Berlioz, and Toulouse in pencil animation run throught the screen, Toulouse stops, takes away the letter R from the title and pushes the right part of it back. the title now reads] the AristoCats Color by Technicolor Story: Larry Clemmons Vance Gerry Ken Anderson Frank Thomas Eric Cleworth Julius Svendsen Ralph Wright Based -

Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 1 year for only $29.99* *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. Subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com, or send a check or money order to: Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480 Be sure to include your name, mailing address, and email address! If you have any questions about subscribing, you can contact us at [email protected] or visit us online! Cover Photography © Garry Rollins Issue 67 Fall 2019 Welcome to Galaxy’s Edge: 64 A Travellers Guide to Batuu Contents Disney News ............................................................................ 8 Calendar of Events ...........................................................17 The Spooky Side MOUSE VIEWS .........................................................19 74 Guide to the Magic of Walt Disney World by Tim Foster...........................................................................20 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................24 Shutters and Lenses by Mike Billick .........................................................................26 Travel Tips Grrrr! 82 by Michael Renfrow ............................................................36 Hangin’ With the Disney Legends by Jamie Hecker ....................................................................38 Bears of Disney Disney Cuisine by Erik Johnson ....................................................................40 -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature

Brown, Noel. " An Interview with Steve Segal." Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature. By Susan Smith, Noel Brown and Sam Summers. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 197–214. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501324949.ch-013>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 03:24 UTC. Copyright © Susan Smith, Sam Summers and Noel Brown 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 97 Chapter 13 A N INTERVIEW WITH STEVE SEGAL N o e l B r o w n Production histories of Toy Story tend to focus on ‘big names’ such as John Lasseter and Pete Docter. In this book, we also want to convey a sense of the animator’s place in the making of the fi lm and their perspective on what hap- pened, along with their professional journey leading up to that point. Steve Segal was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1949. He made his fi rst animated fi lms as a high school student before studying Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he continued to produce award- winning, independent ani- mated shorts. Aft er graduating, Segal opened a traditional animation studio in Richmond, making commercials and educational fi lms for ten years. Aft er completing the cult animated fi lm Futuropolis (1984), which he co- directed with Phil Trumbo, Segal moved to Hollywood and became interested in com- puter animation. -

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Upholding the Disney Utopia Through American Tragedy: a Study of the Walt Disney Company’S Responses to Pearl Harbor and 9/11

Upholding the Disney Utopia Through American Tragedy: A Study of The Walt Disney Company's Responses to Pearl Harbor and 9/11 Lindsay Goddard Senior Thesis presented to the faculty of the American Studies Department at the University of California, Davis March 2021 Abstract Since its founding in October 1923, The Walt Disney Company has en- dured as an influential preserver of fantasy, traditional American values, and folklore. As a company created to entertain the masses, its films often provide a sense of escapism as well as feelings of nostalgia. The company preserves these sentiments by \Disneyfying" danger in its media to shield viewers from harsh realities. Disneyfication is also utilized in the company's responses to cultural shocks and tragedies as it must carefully navigate maintaining its family-friendly reputation, utopian ideals, and financial interests. This paper addresses The Walt Disney Company's responses to two attacks on US soil: the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the attacks on September 11, 200l and examines the similarities and differences between the two. By utilizing interviews from Disney employees, animated film shorts, historical accounts, insignia, government documents, and newspaper articles, this paper analyzes the continuity of Disney's methods of dealing with tragedy by controlling the narrative through Disneyfication, employing patriotic rhetoric, and reiterat- ing the original values that form Disney's utopian image. Disney's respon- siveness to changing social and political climates and use of varying mediums in its reactions to harsh realities contributes to the company's enduring rep- utation and presence in American culture. 1 Introduction A young Walt Disney craftily grabbed some shoe polish and cardboard, donned his father's coat, applied black crepe hair to his chin, and went about his day to his fifth-grade class. -

The Effect of Exposure to an Agressive Cartoon on Children's Play. INSTITUTION Beaver Coll., Glenside, Pa

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 055 297 CG 006 673 AUTHOR Cameron, Samuel M.; And Others TITLE The Effect of Exposure to an Agressive Cartoon on Children's Play. INSTITUTION Beaver Coll., Glenside, Pa. PUB DATE Apr 71 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at Annual Meeting of Eastern Psychological Association, New York, N. Y., April 15-17, 1971 EDRS PRICE MF-S0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Aggression; *Behavior; Behavior Theories; Learning; Pictorial Stimuli; *Play; *Preschool Children; *Stimulus Behavior; Violence; Visual Stimuli ABSTRACT The authors discuss their replications of 2 prominent studies in the area of modeling aggressive behavior; those of Lovaas and Bandura. In the first, they predicted that, given the same socio-economic background, there would be no differences between black and white children in the amount of aggressive play subsequent to viewing an aggressive cartoon. No significant differences are shown between the experimental and control groups for either blacks or whites. The second study, in which 43 pre-schoolers were divided into 3 subject groups, varied the level of aggressive content by showing a different cartoon to each group. It was assumed that the children exposed to the most aggression would emit the most aggressive responses in a subsequent free play period. Again, no significant differences were found. The authors discuss their inability to demonstrate a previously well-documented effect. (TL) TheEffect of Exposure to cm Aggressive Cartoon on Children's Play' - Samuel M, Cameron, Linda K Abraham, and Jean B, Chernicoff Beaver College A series of studies by Bandura and associates (Bandura, Ross, and Ross, 1961; i963) has indicated that children will model novel aggressive behaviors shown by a mai life, film, or ''cartoon"model , These studies also show that aggressive play behaviors other than the ravel ones being modeled will also show an increase subsequent to the child's viewing an aggressive scene-. -

A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2019 FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum Alan Bowers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons Recommended Citation Bowers, Alan, "FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1921. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1921 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum by ALAN BOWERS (Under the Direction of Daniel Chapman) ABSTRACT In my dissertation inquiry, I explore the need for utopian based curriculum which was inspired by Walt Disney’s EPCOT Center. Theoretically building upon such works regarding utopian visons (Bregman, 2017, e.g., Claeys 2011;) and Disney studies (Garlen and Sandlin, 2016; Fjellman, 1992), this work combines historiography and speculative essays as its methodologies. In addition, this project explores how schools must do the hard work of working toward building a better future (Chomsky and Foucault, 1971). Through tracing the evolution of EPCOT as an idea for a community that would “always be in the state of becoming” to EPCOT Center as an inspirational theme park, this work contends that those ideas contain possibilities for how to interject utopian thought in schooling. -

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop.