Anthony Pritchard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alo-Decals-Availability-And-Prices-2020-06-1.Pdf

https://alodecals.wordpress.com/ Contact and orders: [email protected] Availability and prices, as of June 1st, 2020 Disponibilité et prix, au 1er juin 2020 N.B. Indicated prices do not include shipping and handling (see below for details). All prices are for 1/43 decal sets; contact us for other scales. Our catalogue is normally updated every month. The latest copy can be downloaded at https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. N.B. Les prix indiqués n’incluent pas les frais de port (voir ci-dessous pour les détails). Ils sont applicables à des jeux de décalcomanies à l’échelle 1:43 ; nous contacter pour toute autre échelle. Notre catalogue est normalement mis à jour chaque mois. La plus récente copie peut être téléchargée à l’adresse https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. Shipping and handling as of July 15, 2019 Frais de port au 15 juillet 2019 1 to 3 sets / 1 à 3 jeux 4,90 € 4 to 9 sets / 4 à 9 jeux 7,90 € 10 to 16 sets / 10 à 16 jeux 12,90 € 17 sets and above / 17 jeux et plus Contact us / Nous consulter AC COBRA Ref. 08364010 1962 Riverside 3 Hours #98 Krause 4.99€ Ref. 06206010 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #50 Miles 5.99€ Ref. 06206020 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #54 Wietzes 5.99€ Ref. 08323010 1963 Nassau Trophy Race #49 Butler 3.99€ Ref. 06150030 1963 Sebring 12 Hours #11 Maggiacomo-Jopp 4.99€ Ref. 06124010 1964 Sebring 12 Hours #16 Noseda-Stevens 5.99€ Ref. 08311010 1965 Nürburgring 1000 Kms #52 Sparrow-McLaren 5.99€ Ref. -

TOYOTA GAZOO Racing Outlines 2019 Motorsports Activities(E

February7, 2019 Toyota Motor Corporation GAZOO Racing Company TOYOTA GAZOO Racing Outlines 2019 Motorsports Activities TOYOTA GAZOO Racing is a racing company positioning motorsports activities as the basis of our quest to create ever-better cars. From products developed through these activities to the establishment of the GR Garage, TOYOTA GAZOO Racing’s motorsports activities have been promoted as a comprehensive method of increasing numbers of car fans. At last month’s North American International Auto Show in Detroit, we unveiled the new “Supra,” which is set to become the first global model in the GR series line-up. The new Supra incorporates the knowledge and know-how that TOYOTA GAZOO Racing has accumulated thus far, and has been developed with the goal of enabling customers to fully experience the joy of driving. We have positioned the new Supra as our flagship model and, by feeding back knowledge gained through motorsports activities into the development of new products, we intend to further expand the GR series line-up. In 2018, TOYOTA GAZOO Racing achieved the long-desired goal of winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans and also secured the WRC manufacturers’ title, demonstrating that the challenges we have embarked on are leading to concrete results. However, we will not rest on our laurels. In order to deliver the anticipation and excitement of driving to a wider audience, we will engage in the motorsports activities listed below in 2019. TOYOTA GAZOO Racing will compete in the 2019-2020 WEC season. (The driver line-up will be announced at a later date.)With team line-ups, we will also compete in the Nürburgring 24 Hours Endurance Race and other races in Japan respectively. -

Clark Races by Place

www.lotus30.com Jimmy Clark's Competition Data - www.lotus30.com Below is a list of all of the races in which Jimmy Clark competed during his life. The data has been sorted by Place. Source: Gauld, Graham, Jim Clark Remembered, Arco Publishing Company, Inc., New York, 1975 Reprinted with permission kindly given by Graham Gauld. Place (Result) Date Event Circuit Car Comment 1st 6/3/1956 Saloons over 2,000 cc Stobs Camp Sprint Sunbeam Mk3 (Clark's own private car) 1st 9/30/1956 Modified saloons (unlimited) Winfield Sprint Sunbeam Mk3 (Clark's own private car) 1st 9/30/1956 Modified saloons under 1,500 cc Winfield Sprint saloon) 1st 9/30/1956 Saloons under 1,200 cc Winfield Sprint saloon) 1st 9/30/1956 Saloons unlimited Winfield Sprint Sunbeam Mk3 (Clark's own private car) 1st 10/5/1957 BMRC Trophy Charterhall Porsche 1600S (Scott Watson's 1600 Super) 1st 10/6/1957 Modified saloons (unlimited) Winfield Sprint Porsche 1600S (Scott Watson's 1600 Super) 1st 4/5/1958 Racing Cars, over 500 cc Full Sutton Jaguar D-type (Border Rievers D-type chassis XKD 517) 1st 4/5/1958 Sports Cars, unlimited Full Sutton Jaguar D-type (Border Rievers D-type chassis XKD 517) 1st 4/20/1958 Saloons under 2,000 cc Winfield Sprint Porsche 1600S (Scott Watson's 1600 Super) 1st 5/24/1958 Formula Libre Full Sutton Jaguar D-type (Border Rievers D-type chassis XKD 517) 1st 5/24/1958 Saloons and GT Cars, unlimited Full Sutton Porsche 1600S (Scott Watson's 1600 Super) 1st 5/24/1958 Sports Cars, unlimited Full Sutton Jaguar D-type (Border Rievers D-type chassis XKD 517) 1st -

EUROPEAN LE MANS SERIES 4 Hours of Silverstone Qualifying Practice Provisional Classification Nr

EUROPEAN LE MANS SERIES 4 Hours of Silverstone Qualifying Practice Provisional Classification Nr. Team Drivers Car Cl Ty Time Lap Total Gap Kph 1 21 DragonSpeed H. HEDMAN / N. LAPIERRE / B. HANLEY Oreca 07 - Gibson LMP2 D 1:44.040 6 6 - - 204.2 2 32 United Autosports W. OWEN / H. DE SADELEER / F. ALBUQUERQUE LIGIER JSP217 - Gibson LMP2 D 1:44.314 5 5 +0.274 +0.274 203.7 3 39 Graff E. TROUILLET / P. PETIT / E. GUIBBERT Oreca 07 - Gibson LMP2 D 1:45.163 6 7 +1.123 +0.849 202.0 4 22 G-Drive Racing M. ROJAS / R. HIRAKAWA / L. ROUSSEL Oreca 07 - Gibson LMP2 D 1:45.216 6 6 +1.176 +0.053 201.9 5 25 Algarve Pro Racing A. RODA / M. MCMURRY / A. PIZZITOLA LIGIER JSP217 - Gibson LMP2 D 1:45.235 2 3 +1.195 +0.019 201.9 6 34 Tockwith Motorsports N. MOORE / P. HANSON LIGIER JSP217 - Gibson LMP2 D 1:46.397 5 7 +2.357 +1.162 199.7 7 49 High Class Racing D. ANDERSEN / A. FJORDBACH Dallara P217 - Gibson LMP2 D 1:46.408 6 7 +2.368 +0.011 199.6 8 23 Panis Barthez Competition F. BARTHEZ / T. BURET / N. BERTHON LIGIER JSP217 - Gibson LMP2 M 1:46.792 5 7 +2.752 +0.384 198.9 9 28 Idec Sport Racing P. LAFARGUE / P. LAFARGUE / D. ZOLLINGER LIGIER JSP217 - Gibson LMP2 M 1:47.948 6 6 +3.908 +1.156 196.8 10 29 Racing Team Nederland J. LAMMERS / F. -

BRDC Bulletin

BULLETIN BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB DRIVERS’ RACING BRITISH THE OF BULLETIN Volume 30 No 2 • SUMMER 2009 OF THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB Volume 30 No 2 2 No 30 Volume • SUMMER 2009 SUMMER THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB President in Chief HRH The Duke of Kent KG Volume 30 No 2 • SUMMER 2009 President Damon Hill OBE CONTENTS Chairman Robert Brooks 04 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 56 OBITUARIES Directors 10 Damon Hill Remembering deceased Members and friends Ross Hyett Jackie Oliver Stuart Rolt 09 NEWS FROM YOUR CIRCUIT 61 SECRETARY’S LETTER Ian Titchmarsh The latest news from Silverstone Circuits Ltd Stuart Pringle Derek Warwick Nick Whale Club Secretary 10 SEASON SO FAR 62 FROM THE ARCHIVE Stuart Pringle Tel: 01327 850926 Peter Windsor looks at the enthralling Formula 1 season The BRDC Archive has much to offer email: [email protected] PA to Club Secretary 16 GOING FOR GOLD 64 TELLING THE STORY Becky Simm Tel: 01327 850922 email: [email protected] An update on the BRDC Gold Star Ian Titchmarsh’s in-depth captions to accompany the archive images BRDC Bulletin Editorial Board 16 Ian Titchmarsh, Stuart Pringle, David Addison 18 SILVER STAR Editor The BRDC Silver Star is in full swing David Addison Photography 22 RACING MEMBERS LAT, Jakob Ebrey, Ferret Photographic Who has done what and where BRDC Silverstone Circuit Towcester 24 ON THE UP Northants Many of the BRDC Rising Stars have enjoyed a successful NN12 8TN start to 2009 66 MEMBER NEWS Sponsorship and advertising A round up of other events Adam Rogers Tel: 01423 851150 32 28 SUPERSTARS email: [email protected] The BRDC Superstars have kicked off their season 68 BETWEEN THE COVERS © 2009 The British Racing Drivers’ Club. -

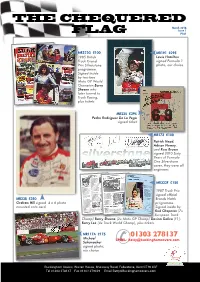

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

Investigation Into the Provenance of the Chassis Owned by Bruce Linsmeyer

Investigation into the provenance of the chassis owned by Bruce Linsmeyer Conducted by Michael Oliver November 2011-August 2012 1 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Design, build and development .............................................................................................................. 6 The month of May ................................................................................................................................ 11 Lotus 56/1 - Qualifying ...................................................................................................................... 12 56/3 and 56/4 - Qualifying ................................................................................................................ 13 The 1968 Indy 500 Race ........................................................................................................................ 14 Lotus 56/1 – Race-day livery ............................................................................................................ -

20 7584 7403 E-Mail [email protected] 1958 Brm Type 25

14 QUEENS GATE PLACE MEWS, LONDON, SW7 5BQ PHONE +44 (0)20 7584 3503 FAX +44 (0)20 7584 7403 E-MAIL [email protected] 1958 BRM TYPE 25 Chassis Number: 258 Described by Sir Stirling Moss as the ‘best-handling and most competitive front-engined Grand Prix car that I ever had the privilege of driving’, the BRM P25 nally gave the British Formula One cognoscenti a rst glimpse of British single seater victory with this very car. The fact that 258 remains at all as the sole surviving example of a P25 is something to be celebrated indeed. Like the ten other factory team cars that were to be dismantled to free up components for the new rear-engined Project 48s in the winter of 1959, 258 was only saved thanks to a directive from BRM head oce in Staordshire on the express wishes of long term patron and Chairman, Sir Alfred Owen who ordered, ‘ensure that you save the Dutch Grand Prix winner’. Founded in 1945, as an all-British industrial cooperative aimed at achieving global recognition through success in grand prix racing, BRM (British Racing Motors) unleashed its rst Project 15 cars in 1949. Although the company struggled with production and development issues, the BRMs showed huge potential and power, embarrassing the competition on occasion. The project was sold in 1952, when the technical regulations for the World Championship changed. Requiring a new 2.5 litre unsupercharged power unit, BRM - now owned by the Owen Organisation -developed a very simple, light, ingenious and potent 4-cylinder engine known as Project 25. -

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0001 Victory Circle #4012, WG 1951 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0002 1959 Sports Car Grand Prix Weekend 1959 D-0003 A Gullwing at Twilight 1959 D-0004 At the IMRRC The Legacy of Briggs Cunningham Jr. 1959 D-0005 Legendary Bill Milliken talks about "Butterball" Nov 6,2004 1959 D-0006 50 Years of Formula 1 On-Board 1959 D-0007 WG: The Street Years Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1948 D-0008 25 Years at Speed: The Watkins Glen Story Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1972 D-0009 Saratoga Automobile Museum An Evening with Carroll Shelby D-0010 WG 50th Anniversary, Allard Reunion Watkins Glen, NY D-0011 Saturday Afternoon at IMRRC w/ Denise McCluggage Watkins Glen Watkins Glen October 1, 2005 2005 D-0012 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival Watkins Glen 2005 D-0013 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen 1952 D-0014 1951-54 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1951-54 D-0015 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend 1952 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1952 D-0016 Ralph E. Miller Collection Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1949 Watkins Glen 1949 D-0017 Saturday Aternoon at the IMRRC, Lost Race Circuits Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 2006 D-0018 2005 The Legends Speeak Formula One past present & future 2005 D-0019 2005 Concours d'Elegance 2005 D-0020 2005 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival, Smalleys Garage 2005 D-0021 2005 US Vintange Grand Prix of Watkins Glen Q&A w/ Vic Elford 2005 D-0022 IMRRC proudly recognizes James Scaptura Watkins Glen 2005 D-0023 Saturday -

Latest Paintings

ULI EHRET WATERCOLOUR PAINTINGS Latest Paintings& BEST OF 1998 - 2015 #4 Auto Union Bergrennwagen - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 30 x 90 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #200 Bernd Rosemeyer „Auto Union 16 Cylinder“ - On canvas: 120 x 160 cm, 100 x 140 cm, 70 x 100 cm, 50 x 70 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #468 Rudolf Carraciola / Mercedes W154 - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 30 x 90 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #52 Hermann Lang „Mercedes Silberpfeil“ #83 Bernd Rosemeyer „Weltrekordfahrt 1936“ - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 30 x 90 cm - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 40 x 80 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #291 Richard Seaman „Donington GP 1937“ - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 40 x 80 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #88 Stirling Moss „Monza Grand Prix 1955“ - On canvas: 120 x 160 cm, 180 x 100 cm, 80 x 150 cm, 60 x 100 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #277 Jean Pierre Wimille „Talbot Lago T26“ - On canvas: 160 x 120 cm, 150 x 100 cm, 120 x 70 cm, 60 x 40 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #469 Tazio Nuvolari / Auto Union D-Type / Coppa Acerbo 1938 - On canvas: 180 x 120 cm, 160 x 90 cm, 140 x 70 cm, 90 x 50 cm, 50 x 30 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm - Original: framed 50 x 70 cm, 1.290 Euros original -

Metal Memory Excerpt.Pdf

In concept, this book started life as a Provenance. As such, it set about to verify the date, location and driver history of the sixth Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa produced, serial number 0718. Many an automotive author has generously given of his time and ink to write about the many limited series competition cars to come from Maranello individually and as a whole. The 250 TR has been often and lovingly included. Much has been scholastic in its veracity, some, adding myth to the legend. After a year's investigation on 0718, and many more on Ferrari's operation, the author has here constructed a family photo album, with interwoven narrative. The narrative is the story that came forward from the author's investigation and richly illustrative interviews conducted into 0718 specifically. To provide a deeper insight into the 250 TR itself we delve into the engineering transformation within Maranello that resulted in the resurrection of the competition V-12 engine, the unique (to the firm at that point) chassis it was placed in, and a body design that gave visual signature to this 1958 customer sports racer. From these elements was composed the publication you now hold. It is the Provenance of a Ferrari, that became the telling of a fifty-year-old mystery, red herrings and all. Table of Contents PROLOGUE 10 CHAPTER TEN TIME CAPSULE 116 CHAPTER ONE THERE IT WAS AGAIN 14 1959 VACA VALLEY GRAND PRIX 135 CHAPTER TWO TRS & MEXICO AT THE TIME 19 CHAPTER ELEVEN RAPIDLY, THROUGH THE CALIFORNIA LANDSCAPE 148 1959 RIVERSIDE GP FOR SPORTSCARS 26 1961 SACRAMENTO -

BELGIAN GRAND PRIX 28 - 30 August

BELGIAN GRAND PRIX 28 - 30 August fter a weekend off, The FIA Formula One World Championship CIRCUIT DE SPA-FRANCORCHAMPS Abegins its third triple-header of 2020, heading to Spa- Length of lap: Francorchamps for Round Seven, the Belgian Grand Prix. 7.004km Lap record: Spa has more outstanding features than many race tracks and its 1:46.286 (Valtteri Bottas, Mercedes, characteristics lead to some interesting set-up decisions. The two 2018) long, full-throttle sections of the first and third sectors push teams to Start line/finish line offset: 0.124km reduce drag – but the longer, intricate middle sector, in which much Total number of race laps: 44 of the lap-time is made or lost, makes for a complicated choice of Total race distance: downforce levels: too high and the car cannot attack or defend on 308.052km the long straights; too low and too much time is lost in the middle Pitlane speed limits: of the lap. It’s a conundrum that often sees teams reach different 80km/h in practice, qualifying, and conclusions – which makes for an interesting grand prix. the race Prompted by a 2019 race in which no driver used the C1 tyre, and CIRCUIT NOTES seven of the ten points-scoring cars ran a one-stop strategy, Pirelli ► The length of the wall on the have chosen to come down a compound for 2020, with the C2, C3 right hand side at the exit of and C4 available this weekend. Turn 1 (Endurance Pit Entry) has been extended. Another potential factor this weekend is the use of fresh engines.