Connecting Science and Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taxonomic Recovery of the Ant Cricket Myrmecophilus Albicinctus from M. Americanus (Orthoptera, Myrmecophilidae)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeysTaxonomic 589: 97–106 (2016)recovery of the ant cricket Myrmecophilus albicinctus from M. americanus... 97 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.589.7739 SHORT COMMUNICATION http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Taxonomic recovery of the ant cricket Myrmecophilus albicinctus from M. americanus (Orthoptera, Myrmecophilidae) Takashi Komatsu1, Munetoshi Maruyama1 1 Kyushu University, Hakozaki 6-10-1, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka 812-8581 Fukuoka, Japan Corresponding author: Takashi Komatsu ([email protected]) Academic editor: F. Montealegre-Z | Received 8 January 2016 | Accepted 12 April 2016 | Published 16 May 2016 http://zoobank.org/9956EB10-A4CE-4933-A236-A34D809645E8 Citation: Komatsu T, Maruyama M (2016) Taxonomic recovery of the ant cricket Myrmecophilus albicinctus from M. americanus (Orthoptera: Myrmecophilidae). ZooKeys 589: 97–106. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.589.7739 Abstract Myrmecophilus americanus and M. albicinctus are typical myrmecophilous insects living inside ant nests. These species are ecologically important due to the obligate association with tramp ant species, includ- ing harmful invasive ant species. However, the taxonomy of these “white-banded ant crickets” is quite confused owing to a scarcity of useful external morphological characteristics. Recently, M. albicinctus was synonymized with M. americanus regardless of the apparent host use difference. To clarify taxonomical relationship between M. albicinctus and M. albicinctus, we reexamined morphological characteristics of both species mainly in the viewpoint of anatomy. Observation of genitalia parts, together with a few external body parts, revealed that M. albicinctus showed different tendency from them of M. americanus. Therefore, we recover M. albicinctus as a distinct species on the basis of the morphology. -

New Pseudophyllinae from the Lesser Antilles (Orthoptera: Ensifera: Tettigoniidae)

Zootaxa 3741 (2): 279–288 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3741.2.6 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:156FF18E-0C3F-468C-A5BE-853CAA63C00F New Pseudophyllinae from the Lesser Antilles (Orthoptera: Ensifera: Tettigoniidae) SYLVAIN HUGEL1 & LAURE DESUTTER-GRANDCOLAS2 1INCI, UPR 3212 CNRS, Université de Strasbourg; 21, rue René Descartes; F-67084 Strasbourg Cedex. E-mail: [email protected] 2Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Département systématique et évolution, UMR 7205 CNRS, Case postale 50 (Entomologie), 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05, France. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Two new Cocconitini Brunner von Wattenwyl, 1895 species belonging to Nesonotus Beier, 1960 are described from the Lesser Antilles: Nesonotus caeruloglobus Hugel, n. sp. from Dominica, and Nesonotus vulneratus Hugel, n. sp. from Martinique. The songs of both species are described and elements of biology are given. The taxonomic status of species close to Nesonotus tricornis (Thunberg, 1815) is discussed. Key words: Orthoptera, Pseudophyllinae, Caribbean, Leeward Islands, Windward islands, Dominica, Martinique Résumé Deux nouvelles sauterelles Cocconotini Brunner von Wattenwyl, 1895 appartenant au genre Nesonotus Beier, 1960 sont décrites des Petites Antilles : Nesonotus caeruloglobus Hugel, n. sp. de Dominique, et Nesonotus vulneratus Hugel, n. sp. de Martinique. Le chant des deux espèces est décrit et des éléments de biologie sont donnés. Le statut taxonomique des espèces proches de Nesonotus tricornis (Thunberg, 1815) est discuté. Introduction Cocconotini species occur in most of the Lesser Antilles islands, including small and dry ones such as Terre de Haut in Les Saintes micro archipelago (S. -

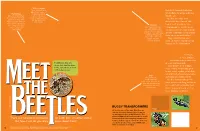

Buggy Transformers

Wing Coverings They’re called elytra It’s liftoff! A scarab beetle (see (EL-ih-truh), and most Flight Wings beetles have them. photo) flaps its wings and rises Also called hind wings, Elytra are hard and into the air. they’re thin and delicate. tough. They protect the Beetles aren’t the best When not being used, delicate flight wings they fold under the elytra. underneath. fliers in the insect world. But But when it’s time to fly, that doesn’t stop them from these wings pop open Antennas and beat up and Most beetles use them being among the world’s great- down rapidly. for smelling. But some est success stories. Out of all the can use them for tasting, feeling, or even swimming species of animals on our planet, or fighting! They can be three out of ten are beetles! shaped like clubs, saw blades, feathers, They crawl, fly, hop, and or strings of beads. swim on every continent except Antarctica. You’ll find them in forests, deserts, prairies, mountain regions, and even Fossils like this one in your own backyard. show that beetles have Some beetles look strange. been around for at least Parts of their bodies may grow 300 million years. horns, crests, spikes, or brushes. Several beetles have long snouts, Legs Like all insects, and many are wildly colorful. beetles have six Beetles do weird things, too. jointed legs. Most beetles have two tiny claws on Some species eat dung, and a few the tip of each leg for even squirt out hot liquids. -

Growing a Wild NYC: a K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum Was Made Possible Through the Generous Support of Our Funders

A K-5 URBAN POLLINATOR CURRICULUM Growing a Wild NYC LESSON 1: HABITAT HUNT The National Wildlife Federation Uniting all Americans to ensure wildlife thrive in a rapidly changing world Through educational programs focused on conservation and environmental knowledge, the National Wildlife Federation provides ways to create a lasting base of environmental literacy, stewardship, and problem-solving skills for today’s youth. Growing a Wild NYC: A K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum was made possible through the generous support of our funders: The Seth Sprague Educational and Charitable Foundation is a private foundation that supports the arts, housing, basic needs, the environment, and education including professional development and school-day enrichment programs operating in public schools. The Office of the New York State Attorney General and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation through the Greenpoint Community Environmental Fund. Written by Nina Salzman. Edited by Sarah Ward and Emily Fano. Designed by Leslie Kameny, Kameny Design. © 2020 National Wildlife Federation. Permission granted for non-commercial educational uses only. All rights reserved. September - January Lesson 1: Habitat Hunt Page 8 Lesson 2: What is a Pollinator? Page 20 Lesson 3: What is Pollination? Page 30 Lesson 4: Why Pollinators? Page 39 Lesson 5: Bee Survey Page 45 Lesson 6: Monarch Life Cycle Page 55 Lesson 7: Plants for Pollinators Page 67 Lesson 8: Flower to Seed Page 76 Lesson 9: Winter Survival Page 85 Lesson 10: Bee Homes Page 97 February -

James K. Wetterer

James K. Wetterer Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University 5353 Parkside Drive, Jupiter, FL 33458 Phone: (561) 799-8648; FAX: (561) 799-8602; e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, Seattle, WA, 9/83 - 8/88 Ph.D., Zoology: Ecology and Evolution; Advisor: Gordon H. Orians. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY, East Lansing, MI, 9/81 - 9/83 M.S., Zoology: Ecology; Advisors: Earl E. Werner and Donald J. Hall. CORNELL UNIVERSITY, Ithaca, NY, 9/76 - 5/79 A.B., Biology: Ecology and Systematics. UNIVERSITÉ DE PARIS III, France, 1/78 - 5/78 Semester abroad: courses in theater, literature, and history of art. WORK EXPERIENCE FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY, Wilkes Honors College 8/04 - present: Professor 7/98 - 7/04: Associate Professor Teaching: Biodiversity, Principles of Ecology, Behavioral Ecology, Human Ecology, Environmental Studies, Tropical Ecology, Field Biology, Life Science, and Scientific Writing 9/03 - 1/04 & 5/04 - 8/04: Fulbright Scholar; Ants of Trinidad and Tobago COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, Department of Earth and Environmental Science 7/96 - 6/98: Assistant Professor Teaching: Community Ecology, Behavioral Ecology, and Tropical Ecology WHEATON COLLEGE, Department of Biology 8/94 - 6/96: Visiting Assistant Professor Teaching: General Ecology and Introductory Biology HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Museum of Comparative Zoology 8/91- 6/94: Post-doctoral Fellow; Behavior, ecology, and evolution of fungus-growing ants Advisors: Edward O. Wilson, Naomi Pierce, and Richard Lewontin 9/95 - 1/96: Teaching: Ethology PRINCETON UNIVERSITY, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology 7/89 - 7/91: Research Associate; Ecology and evolution of leaf-cutting ants Advisor: Stephen Hubbell 1/91 - 5/91: Teaching: Tropical Ecology, Introduction to the Scientific Method VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY, Department of Psychology 9/88 - 7/89: Post-doctoral Fellow; Visual psychophysics of fish and horseshoe crabs Advisor: Maureen K. -

James K. Wetterer

James K. Wetterer Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University 5353 Parkside Drive, Jupiter, FL 33458 Phone: (561) 799-8648; FAX: (561) 799-8602; e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, Seattle, WA, 9/83 - 8/88 Ph.D., Zoology: Ecology and Evolution; Advisor: Gordon H. Orians. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY, East Lansing, MI, 9/81 - 9/83 M.S., Zoology: Ecology; Advisors: Earl E. Werner and Donald J. Hall. CORNELL UNIVERSITY, Ithaca, NY, 9/76 - 5/79 A.B., Biology: Ecology and Systematics. UNIVERSITÉ DE PARIS III, France, 1/78 - 5/78 Semester abroad: courses in theater, literature, and history of art. WORK EXPERIENCE FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY, Wilkes Honors College 8/04 - present: Professor 7/98 - 7/04: Associate Professor Teaching: Principles of Ecology, Behavioral Ecology, Human Ecology, Environmental Studies, Tropical Ecology, Biodiversity, Life Science, and Scientific Writing 9/03 - 1/04 & 5/04 - 8/04: Fulbright Scholar; Ants of Trinidad and Tobago COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, Department of Earth and Environmental Science 7/96 - 6/98: Assistant Professor Teaching: Community Ecology, Behavioral Ecology, and Tropical Ecology WHEATON COLLEGE, Department of Biology 8/94 - 6/96: Visiting Assistant Professor Teaching: General Ecology and Introductory Biology HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Museum of Comparative Zoology 8/91- 6/94: Post-doctoral Fellow; Behavior, ecology, and evolution of fungus-growing ants Advisors: Edward O. Wilson, Naomi Pierce, and Richard Lewontin 9/95 - 1/96: Teaching: Ethology PRINCETON UNIVERSITY, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology 7/89 - 7/91: Research Associate; Ecology and evolution of leaf-cutting ants Advisor: Stephen Hubbell 1/91 - 5/91: Teaching: Tropical Ecology, Introduction to the Scientific Method VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY, Department of Psychology 9/88 - 7/89: Post-doctoral Fellow; Visual psychophysics of fish and horseshoe crabs Advisor: Maureen K. -

Research Article Nonintegrated Host Association of Myrmecophilus Tetramorii, a Specialist Myrmecophilous Ant Cricket (Orthoptera: Myrmecophilidae)

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Psyche Volume 2013, Article ID 568536, 5 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/568536 Research Article Nonintegrated Host Association of Myrmecophilus tetramorii, a Specialist Myrmecophilous Ant Cricket (Orthoptera: Myrmecophilidae) Takashi Komatsu,1 Munetoshi Maruyama,2 and Takao Itino1,3 1 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Shinshu University, 3-1-1 Asahi, Matsumoto, Nagano 390-8621, Japan 2 Kyushu University Museum, Hakozaki 6-10-1, Fukuoka 812-8581, Japan 3 Institute of Mountain Science, Shinshu University, 3-1-1 Asahi, Matsumoto, Nagano 390-8621, Japan Correspondence should be addressed to Takashi Komatsu; [email protected] Received 10 January 2013; Accepted 19 February 2013 Academic Editor: Alain Lenoir Copyright © 2013 Takashi Komatsu et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Myrmecophilus ant crickets (Orthoptera: Myrmecophilidae) are typical ant guests. In Japan, about 10 species are recognized on the basis of morphological and molecular phylogenetic frameworks. Some of these species have restricted host ranges and behave intimately toward their host ant species (i.e., they are host specialist). We focused on one species, M. tetramorii, which uses the myrmicine ant Tetramorium tsushimae as its main host. All but one M. tetramorii individuals were collected specifically from nests of T. tsushimae in the field. However, behavioral observation showed that all individuals used in the experiment received hostile reactions from the host ants. There were no signs of intimate behaviors such as grooming of hosts or receipt of mouth-to-mouth feeding from hosts, which are seen in some host-specialist Myrmecophilus species among obligate host-ant species. -

Encyclopedia of Social Insects

G Guests of Social Insects resources and homeostatic conditions. At the same time, successful adaptation to the inner envi- Thomas Parmentier ronment shields them from many predators that Terrestrial Ecology Unit (TEREC), Department of cannot penetrate this hostile space. Social insect Biology, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium associates are generally known as their guests Laboratory of Socioecology and Socioevolution, or inquilines (Lat. inquilinus: tenant, lodger). KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium Most such guests live permanently in the host’s Research Unit of Environmental and nest, while some also spend a part of their life Evolutionary Biology, Namur Institute of cycle outside of it. Guests are typically arthropods Complex Systems, and Institute of Life, Earth, associated with one of the four groups of eusocial and the Environment, University of Namur, insects. They are referred to as myrmecophiles Namur, Belgium or ant guests, termitophiles, melittophiles or bee guests, and sphecophiles or wasp guests. The term “myrmecophile” can also be used in a broad sense Synonyms to characterize any organism that depends on ants, including some bacteria, fungi, plants, aphids, Inquilines; Myrmecophiles; Nest parasites; and even birds. It is used here in the narrow Symbionts; Termitophiles sense of arthropods that associated closely with ant nests. Social insect nests may also be parasit- Social insect nests provide a rich microhabitat, ized by other social insects, commonly known as often lavishly endowed with long-lasting social parasites. Although some strategies (mainly resources, such as brood, retrieved or cultivated chemical deception) are similar, the guests of food, and nutrient-rich refuse. Moreover, nest social insects and social parasites greatly differ temperature and humidity are often strictly regu- in terms of their biology, host interaction, host lated. -

Os Nomes Galegos Dos Insectos 2020 2ª Ed

Os nomes galegos dos insectos 2020 2ª ed. Citación recomendada / Recommended citation: A Chave (20202): Os nomes galegos dos insectos. Xinzo de Limia (Ourense): A Chave. https://www.achave.ga /wp!content/up oads/achave_osnomesga egosdos"insectos"2020.pd# Fotografía: abella (Apis mellifera ). Autor: Jordi Bas. $sta o%ra est& su'eita a unha licenza Creative Commons de uso a%erto( con reco)ecemento da autor*a e sen o%ra derivada nin usos comerciais. +esumo da licenza: https://creativecommons.org/ icences/%,!nc-nd/-.0/deed.g . 1 Notas introdutorias O que cont n este documento Na primeira edición deste recurso léxico (2018) fornecéronse denominacións para as especies máis coñecidas de insectos galegos (e) ou europeos, e tamén para algúns insectos exóticos (mostrados en ám itos divulgativos polo seu interese iolóxico, agr"cola, sil!"cola, médico ou industrial, ou por seren moi comúns noutras áreas xeográficas)# Nesta segunda edición (2020) incorpórase o logo da $%a!e ao deseño do documento, corr"xese algunha gralla, reescr" ense as notas introdutorias e engádense algunhas especies e algún nome galego máis# &n total, ac%éganse nomes galegos para 89( especies de insectos# No planeta téñense descrito aproximadamente un millón de especies, e moitas están a"nda por descubrir# Na )en"nsula * érica %a itan preto de +0#000 insectos diferentes# Os nomes das ol oretas non se inclúen neste recurso léxico da $%a!e, foron o xecto doutro tra allo e preséntanse noutro documento da $%a!e dedicado exclusivamente ás ol oretas, a!ela"ñas e trazas . Os nomes galegos -

Wood As We Know It: Insects in Veteris (Highly Decomposed) Wood

Chapter 22 It’s the End of the Wood as We Know It: Insects in Veteris (Highly Decomposed) Wood Michael L. Ferro Living trees are all alike, every decaying tree decays in its own way. —with apologies to Tolstoy Abstract The final decay stage of wood, termed veteris wood, is a dynamic habitat that harbors high biodiversity and numerous species of conservation concern and is vital for keystone and economically important species. Veteris wood is characterized by chemical and structural degradation, including absence of bark, oval bole shape, and invasion by roots, and includes red rot, mudguts, and sufficiently decayed wood in living trees and veteran trees. Veteris wood may represent up to 50% of the volume of woody debris in forests and can persist from decades to centuries. Economically important and keystone species such as the black bear [Ursus americanus (Pallas)] and pileated woodpecker [Dryocopus pileatus (L.)] are directly impacted by veteris wood. Nearly every order of insect contains members dependent on veteris wood, including species of conservation concern such as Lucanus cervus (L) (Lucanidae) and Osmoderma eremita (Scopoli) (Scarabaeidae). Due to the extreme time needed for formation, veteris wood may be of particular conservation concern. Veteris wood is ideal for research because invertebrates within it can be collected immediately after sampling. Imaging techniques such as Lidar, photogram- metry, and sound tomography allow for modeling the interior and exterior aspects of woody debris, including veteran trees, and, if coupled with faunal surveys, would make veteris wood and veteran trees some of the best understood keystone habitats. M. L. Ferro (*) Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, Clemson University Arthropod Collection, 277 Poole Agricultural Center, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA This is a U.S. -

New Canadian and Ontario Orthopteroid Records, and an Updated Checklist of the Orthoptera of Ontario

Checklist of Ontario Orthoptera (cont.) JESO Volume 145, 2014 NEW CANADIAN AND ONTARIO ORTHOPTEROID RECORDS, AND AN UPDATED CHECKLIST OF THE ORTHOPTERA OF ONTARIO S. M. PAIERO1* AND S. A. MARSHALL1 1School of Environmental Sciences, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G 2W1 email, [email protected] Abstract J. ent. Soc. Ont. 145: 61–76 The following seven orthopteroid taxa are recorded from Canada for the first time: Anaxipha species 1, Cyrtoxipha gundlachi Saussure, Chloroscirtus forcipatus (Brunner von Wattenwyl), Neoconocephalus exiliscanorus (Davis), Camptonotus carolinensis (Gerstaeker), Scapteriscus borellii Linnaeus, and Melanoplus punctulatus griseus (Thomas). One further species, Neoconocephalus retusus (Scudder) is recorded from Ontario for the first time. An updated checklist of the orthopteroids of Ontario is provided, along with notes on changes in nomenclature. Published December 2014 Introduction Vickery and Kevan (1985) and Vickery and Scudder (1987) reviewed and listed the orthopteroid species known from Canada and Alaska, including 141 species from Ontario. A further 15 species have been recorded from Ontario since then (Skevington et al. 2001, Marshall et al. 2004, Paiero et al. 2010) and we here add another eight species or subspecies, of which seven are also new Canadian records. Notes on several significant provincial range extensions also are given, including two species originally recorded from Ontario on bugguide.net. Voucher specimens examined here are deposited in the University of Guelph Insect Collection (DEBU), unless otherwise noted. New Canadian records Anaxipha species 1 (Figs 1, 2) (Gryllidae: Trigidoniinae) This species, similar in appearance to the Florida endemic Anaxipha calusa * Author to whom all correspondence should be addressed. -

Insect Stuff.Indd

COLEOPTERA AROUND THE WORLD Purpose of activity: To get an overview of the great variety of insects within the order Coleoptera. Description of game: Players listen to clues about beetles and weevils, and then try to guess which one is being described. They find the picture on the map and put their token on it. When the answer is given, if they were correct, they receive a picture of that beetle to pin onto their “collection.” The clues can be adjusted to suit the knowledge level of your players. There isn’t any official “winner” of the game. This might sound lame, but it actually worked very well in my classroom. They were very enthusiastic simply about collecting and pin- ning the beetle pictures. Target age group: 8 to 12 Time needed: For set up, about 15 minutes or so (just some cutting and a little pasting). For playing, the time can be very flexible. You need not use all the insects if time is short. Materials needed: -- color copies of the pattern pages -- scissors -- glue stick and clear tape -- tokens to mark player positions on map -- long pins (such as quilting pins that have a colored ball at the top) -- a Styrofoam or cardboard sheet onto which the insect pictures can be pinned NOTE: If using pins is not an option, the pictures can be tacked with glue stick onto a piece of paper. How to set up: 1) Trim off the edges that are labeled TRIM. 2) Put the 6 map sections together to make the board. The trimmed edges will overlap onto the untrimmed edges.