Reputation, Celebrity, and the Idea of the Victorian Gentleman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nineteenth-Century British Women Travel Writers and Sport Precious Mckenzie-Stearns University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2007 Venturesome women: Nineteenth-century British women travel writers and sport Precious McKenzie-Stearns University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation McKenzie-Stearns, Precious, "Venturesome women: Nineteenth-century British women travel writers and sport" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2284 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Venturesome Women: Nineteenth-Century British Women Travel Writers and Sport by Precious McKenzie-Stearns A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Pat Rogers, Ph.D. Nancy Jane Tyson, Ph.D. Regina Hewitt, Ph.D. Carolyn Eichner, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 30, 2007 Keywords: sport, bird, kingsley, savory, dixie © Copyright 2007 , Precious McKenzie-Stearns Dedication For Colby and Wyatt Acknowledgements I must begin by acknowledging the members of my committee: Professors Pat Rogers, Nancy Jane Tyson, Regina Hewitt and Carolyn Eichner. Dr. Rogers has given generously of his time throughout this project. He has kindly allowed me the freedom to pursue my academic interests and tackle a noncanonical topic. Dr. Tyson has introduced me to the New Women’s movement and its authors through both her phenomenal course on Victorian Literature and during our lively meetings. -

Miss Lisa Brown's Guide to Dressing for a Regency Ball – Gentlemen's

MMiissss LLiissaa BBrroowwnn’’ss GGuuiiddee ttoo DDrreessssiinngg ffoorr aa RReeggeennccyy BBaallll –– GGeennttlleemmeenn’’ss EEddiittiioonn (and remove string!) Shave Jane Austen & the Regency face every Wednesday and The term “Regency” refers to years between 1811 Sunday as per regulations. and 1820 when George III of the United Kingdom was deemed unfit to rule and his son, later George Other types of facial hair IV, was installed as his proxy with the title of were not popular and were “Prince Regent”. However, “Regency Era” is often not allowed in the military. applied to the years between 1795 and 1830. This No beards, mustaches, period is often called the “Extended Regency” goatees, soul patches or because the time shared the same distinctive culture, Van Dykes. fashion, architecture, politics and the continuing Napoleonic War. If you have short hair, brush it forward into a Caesar cut style The author most closely associated with the with no discernable part. If your Regency is Jane Austen (1775-1817). Her witty and hair is long, put it into a pony tail engaging novels are a window into the manners, at the neck with a bow. lifestyle and society of the English gentry. She is the ideal connexion to English Country Dancing as Curly hair for both men and each of her six books: Pride and Prejudice , Sense women was favored over straight and Sensibility , Emma , Persuasion , Mansfield Par k hair. Individual curls were made and Northanger Abbey, feature balls and dances. with pomade (hair gel) and curling papers. Hair If you are unable to assemble much of a Regency wardrobe, you can still look the part by growing your sideburns The Minimum and getting a Caesar cut If you wish to dress the part of a country gentleman hairstyle. -

Introduction to Edwardian England

Edwardian Beverley: a snapshot in time How much do you know about the Edwardian era in England? Strictly, it was the time of King Edward VII’s brief reign from 1901 to 1910, but is usually considered to extend up to the start of war in 1914. It is often seen as a ‘golden age’, when the world paused between the busy industrialisation of the Victorians and the chaos of global war, after which life changed forever. However, although the Edwardian period was short it was a time of great change, from social reforms to fashion trends and technological advances. One of the key technological developments of the period was the introduction of Kodak’s Brownie camera in 1900, which enabled everybody to make their own record of their surroundings. There is therefore a wonderful photographic record of life in Beverley from the turn of the century, which we have drawn upon in this exhibition as we attempt to put the town into the context of the wider world. Museum Group Collection Online. Science (Y1988.43.3) Creative Commons Licence. 1900 Box Brownie camera Introduction to Edwardian England Samuel Hynes described the Edwardian era as a “leisurely time when There were significant technological advancements, especially in mass women wore picture hats and did not vote, when the rich were not communication (the first wireless signal across the Atlantic was sent in ashamed to live conspicuously and the sun really never set on the British 1901), leisure and entertainment, particularly with the development of the flag”. This perception of a romantic age of long summer afternoons and cinema. -

Victorian Representations of Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU Honors Theses, 1963-2015 Honors Program 2015 Victorian Representations of Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I Grace K. Butkowski College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Butkowski, Grace K., "Victorian Representations of Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I" (2015). Honors Theses, 1963-2015. 69. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/honors_theses/69 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, 1963-2015 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Grace Butkowski Victorian Representations of Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I The rivalry of Mary, Queen of Scots and her English cousin Elizabeth I is a storied one that has consumed both popular and historical imaginations since the two queens reigned in the sixteenth century. It is often portrayed as a tale of contrasts: on one end, Gloriana with her fabled red hair and virginity, the bastion of British culture and Protestant values, valiantly defending England against the schemes of the Spanish and their Armada. On the other side is Mary, Queen of Scots, the enchanting and seductive French-raised Catholic, whose series of tragic, murderous marriages gave birth to both the future James I of England and to schemes surrounding the English throne. -

WHAT IS REGENCY? by Blair Bancroft

WHAT IS REGENCY? By Blair Bancroft Special Note: After Signet and Zebra shut down their traditional Regency lines, I considered scrapping this article, but fortunately trads are showing signs of struggling back to life due to the devotion of authors, readers, small presses, and e-publishers. And, besides, I love the Regency era enough that I’m reluctant to turn my back on the wit and style of Jane Austen, who started it all, or Georgette Heyer, who began the modern revival of what we call “Regency.” Interestingly, what most of us love about these primarily squeaky clean peeks into Britain at the time of Napoleonic wars is exactly what killed them—an emphasis on style, language, and customs of the times, as opposed to the high drama and hot sex of many Regency-set Historicals. So below is my original essay on “What is Regency,” with only a minor update here and there. Hopefully, it will still be helpful to authors attempting to understand why writing in the honored tradition of Jane Austen and Georgette Heyer is not going to get you a New York publisher in this first decade of the twenty-first century. * * * Having been a Regency buff for more years than I care to remember, it was something of a shock to discover my much beloved genre had become the latest rage in Historical Romance. Will it last, or will it bleed to death from some of the massacres perpetrated by authors who may not even know what the “Regency” is, let alone its style, language, clothing, and customs. -

Introduction

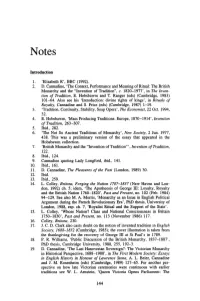

Notes Introduction 1. 'Elizabeth R·. BBC (1992). 2. D. Cannadine. 'The Context. Perfonnance and Meaning of Ritual: The British Monarchy and the "Invention of Tradition". c. 1820-1977'. in The Inven tion of Tradition. E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger (eds) (Cambridge. 1983) 101-64. Also see his 'Introduction: divine rights of kings'. in Rituals of Royalty. Cannadine and S. Price (eds) (Cambridge. 1987) 1-19. 3. 'Tradition. Continuity. Stability. Soap Opera'. The Economist. 22 Oct. 1994. 32. 4. E. Hobsbawm. 'Mass Producing Traditions: Europe. 1870-1914'. Invention of Tradition. 263-307. 5. Ibid .• 282. 6. 'The Not So Ancient Traditions of Monarchy'. New Society. 2 Jun. 1977. 438. This was a preliminary version of the essay that appeared in the Hobsbawm collection. 7. 'British Monarchy and the "Invention of Tradition"'. Invention of Tradition. 122. 8. Ibid .• 124. 9. Cannadine quoting Lady Longford. ibid .• 141. 10. Ibid .• 161. 11. D. Cannadine. The Pleasures of the Past (London. 1989) 30. 12. Ibid. 13. Ibid .• 259. 14. L. Colley. Britons, Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (New Haven and Lon don. 1992) ch. 5; idem. 'The Apotheosis of George ill: Loyalty. Royalty and the British Nation 1760-1820'. Past and Present. no. 102 (Feb. 1984) 94-129. See also M. A. Morris. 'Monarchy as an Issue in English Political Argument during the French Revolutionary Era'. PhD thesis. University of London. 1988. esp. ch. 7. 'Royalist Ritual and the Support of the State'. 15. L. Colley. 'Whose Nation? Class and National Consciousness in Britain 1750-1830'. Past and Present. no. 113 (November 1986) 117. 16. -

Land and Sea Published by Aberdeen University Press

JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 10, Issue 1 Land and Sea Published by Aberdeen University Press in association with The Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies ISSN 1753-2396 Contents The Missing Emigrants: The Wreck of the Exmouth and John Francis Campbell of Islay Sara Stevenson 1 Spin Doctors or Informed Lobbyists? The Voices of Four Presbyterian Ministers in the Emigration of Scots to the Antipodes, 1840–80 Jill Harland 21 Celt, Gael or English? British Ethnic Empathy to Indigenes in the Empire from the Records of British Battalions in the Sub-Continent Peter Karsten 50 ‘The Evils Which Have Arisen in My Country’: Mary Power Lalor and Active Female Landlordism during the Land Agitation Andrew G. Newby 71 The Scottish Landed Estate: Break-up or Survival? Ewen A. Campbell 95 Purpose and the Irish Landed Gentry: The Case of Arthur Hugh Smith Barry, 1843–1925 Ian d’Alton 117 List of Contributors 142 Editorial In recent literature both the Irish and the Scots have been described as ‘migrant peoples’, and both nations have a constantly refreshed relationship with an identifi ed global diaspora. These diaspora in turn exercise real political and cultural power across the Anglophone world. Yet this characteristic of these two Celtic peoples was a direct consequence of the politics of place in the homeland. Both Ireland and Scotland had, and continue to have, a contested relationship to the divisions and subdivisions, the management and improvement of the agricultural land which they inhabit. The Great Famine and the Clearances attest to that. This issue of the Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies brings together a set of occasional papers which refl ect on the complex weave of migration and the politics of land since the nineteenth century. -

Dear Fiona: Letters from a Suspected Soviet

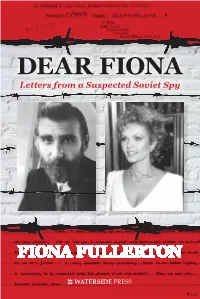

In this poignant and revealing memoir, Fiona DEAR FIONA FIONA DEAR Fullerton tells for the first time the story of Letters from a Suspected Soviet Spy her friendship with Alex Alexandrowicz a category-A high security prisoner who was He was a suspected Cold War spy. to serve 22 years for a crime he didn’t com- mit. Based on their original letters to each She was a KGB double agent in a Bond movie. other, the narrative is one of startling con- trasts — the darkness of a man incarcerated When a prisoner writes to a movie star, the best DEAR FIONA and a woman surrounded by the brightest he can hope for is a signed photo. But when lights of show business. Alex Alexandrowicz wrote to glamorous actress Letters from a Suspected Soviet Spy Fiona Fullerton, he didn’t expect it to lead to a “It is you alone who has given me strength while friendship spanning 30 years. I have been in prison, the strength to restore lost and dying hope into burning resolution”. Fiona Fullerton was for 30 years a leading The book uncovers Alex’s tender poetry, FIONA FULLERTON actress in theatre, television and films. She prison diaries and artwork, often produced is now a property guru, journalist, interior in solitary confinement while Fiona shares designer and author of three books about her doubts about the fragility of celebrity. investing in the property market. She lives in the Cotswolds with her husband and two “Have you ever heard of Nadejda Philaretovna children. von Meck? She and Tchaikovsky were corre- sponding for years, they never met — and yet he produced his finest work for her. -

Entertainment in the Regency

1 Entertainment In the Regency Era Delivered to the Jane Austen Club Calgary Alberta. May 18, 2013 by Ann Craig. Sir 2 When being a part of the audience at other Jasna meeting I often thought about different aspects of the world in Jane’s life and her novels. It’s great looking into different ages on the internet because there is so much information – too much sometimes, in fact, you really can get monumentally side tracked – in fact sometimes forget why you started…..right! I have included some information about the royal family and the different levels of the society because it did play role in who one associates with or not. The goings on in London with royalty got back to the smaller towns and influenced their way of life in how they entertained and who they entertained. If you had an association with members of the royal family, your position in the community would be greatly enhanced. George III in 1762, In Jane’s time, George 111 was the king with his older son George, the Prince of Wales, who later went on to being the Prince Regent and then King George 1V Families members to the king or Queen - sons, daughters brothers sisters aunts uncles etc. etc.etc.ect., were given titles so that everyone would know who they were and so understand how important they all were.- regardless of wealth, looks or intelligence. 3 Sir Walter Elliot is such a case in point. Sir Walter Elliot as played by Colin Redgrave He lives and breathes the importance of “Baronetage” the book that lists all the titled people of which he is one –it is interesting to note that his title was due to his father not for anything he did. -

Leicestershire Worthies1 the Squire De Lisle

LEICESTERSHIRE WORTHIES1 The Squire De Lisle When asked to prepare my Presidential valedictory lecture, I pondered and discussed the approach with the late lamented Dr Alan McWhirr (1937–2010). We decided that it would be a good idea to present a short synopsis of some of our distinguished citizens and to give the talk the title Leicestershire Worthies. I undertook some preliminary research and found that we lacked many details of their lives and many of their portraits. Wherever appropriate I asked the help of my hearers and finally prepared a Curriculum Vitae for 29 people together with their portraits, with the sole exception of Joseph Cradock who is unfortunately still unpictured. The lecture was delivered on October 6th 2011 and I am very pleased that it is being published as I sincerely hope that there are amongst our members some who will be able to help fill the gaps, or even be able to provide better portraits of some of the Worthies. I hope this paper will stimulate further interest in the many and various strands of the history of our county. Squire Gerard De Lisle 1 This paper, entitled Leicestershire Worthies, was delivered by our President, Gerard De Lisle, in October 2011 in the final year of his Presidency. Squire De Lisle was our second three-year President. This paper is presented in the author’s preferred format of an illustrated catalogue. Jill Bourne Hon. Ed. Trans. Leicestershire Archaeol. and Hist. Soc., 87 (2013) 04_de Lisle_015-040.indd 17 26/09/2013 16:44 18 Squire De Lisle I owe a debt of gratitude to many persons who have helped me in this task.2 1. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Marshall, William The creation of Yorkshireness: Cultural identities in Yorkshire c.1850-1918 Original Citation Marshall, William (2011) The creation of Yorkshireness: Cultural identities in Yorkshire c.1850- 1918. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/12302/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ he creation of Yorkshireness Cultural identities in Yorkshire c.1850-1918 WILLIAM MARSHALL A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersield in partial fulilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy he University of Huddersield September 2011 Abstract THE rapid expansion, wider distribution and increased readership of print media in the latter half of the nineteenth century helped to foster the process that has been described as the nationalisation of English culture. -

Elena Rebekka Götting Phd Thesis

CHALLENGING MALENESS – THE NEW WOMAN’S ATTEMPTS TO RECONSTRUCT THE BINARY CODE Elena Rebekka Götting A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2014 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/6612 This item is protected by original copyright Challenging Maleness – The New Woman’s Attempts to Reconstruct the Binary Code Elena Rebekka Götting This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Ph.D. at the University of St Andrews 20.09.2013 Abstract iii THESIS ABSTRACT This thesis explores the construction of masculinity in novels written by New Women authors between the years 1881-1899. The fin de siècle was a period during which gender roles were renegotiated with fervour by both male and female authors, but it was the so-called New Woman in particular who was trying to transform the Victorian notion of femininity to incorporate the demands of the burgeoning women’s movement. This thesis argues that in their fiction, New Women authors often tried to achieve this transformation by creating male characters who were designed to justify and to mitigate the New Woman protagonist’s departure from traditional structures of heterosexual relationships. The methodology underlying this thesis is the notion that men and women were perceived as binary opposites during the Victorian period. I refer to this as the binary code of the sexes. This code assumes that men and women naturally possess diametrically opposed character attributes, and also that “masculine” attributes are perforce better than “feminine” ones.