Heralding a New Enlightenment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transplanting Surrealism in Greece- a Scandal Or Not?

International Journal of Social and Educational Innovation (IJSEIro) Volume 2 / Issue 3/ 2015 Transplanting Surrealism in Greece- a Scandal or Not? NIKA Maklena University of Tirana, Albania E-mail: [email protected] Received 26.01.2015; Accepted 10.02. 2015 Abstract Transplanting the surrealist movement and literature in Greece and feedback from the critics and philological and journalistic circles of the time is of special importance in the history of Modern Greek Literature. The Greek critics and readers who were used to a traditional, patriotic and strictly rule-conforming literature would find it hard to accept such a kind of literature. The modern Greek surrealist writers, in close cooperation mainly with French surrealist writers, would be subject to harsh criticism for their surrealist, absurd, weird and abstract productivity. All this reaction against the transplanting of surrealism in Greece caused the so called “surrealist scandal”, one of the biggest scandals in Greek letters. Keywords: Surrealism, Modern Greek Literature, criticism, surrealist scandal, transplanting, Greek letters 1. Introduction When Andre Breton published the First Surrealist Manifest in 1924, Greece had started to produce the first modern works of its literature. Everything modern arrives late in Greece due to a number of internal factors (poetic collection of Giorgios Seferis “Mythistorima” (1935) is considered as the first modern work in Greek literature according to Αlexandros Argyriou, History of Greek Literature and its perception over years between two World Wars (1918-1940), volume Α, Kastanioti Publications, Athens 2002, pp. 534-535). Yet, on the other hand Greek writers continued to strongly embrace the new modern spirit prevailing all over Europe. -

The Explorations and Poetic Avenues of Nikos Kavvadias

THE EXPLORATIONS AND POETIC AVENUES OF NIKOS KAVVADIAS IAKOVOS MENELAOU * ABSTRACT. This paper analyses some of the influences in Nikos Kavvadias’ (1910-1975) poetry. In particular – and without suggesting that such topic in Kavvadias’ poetry ends here – we will examine the influences of the French poet Charles Baudelaire and the English poet John Mase- field. Kavvadias is perhaps a sui generis case in Modern Greek literature, with a very distinct writing style. Although other Greek poets also wrote about the sea and their experiences during their travelling, Kavvadias’ references and descriptions of exotic ports, exotic women and cor- rupt elements introduce the reader into another world and dimension: the world of the sailor, where the fantasy element not only exists, but excites the reader’s imagination. Although the world which Kavvadias depicts is a mixture of fantasy with reality—and maybe an exaggerated version of the sailor’s life, the adventures which he describes in his poems derive from the ca- pacity of the poetic ego as a sailor and a passionate traveller. Without suggesting that Kavvadias wrote some sort of diary-poetry or that his poetry is clearly biographical, his poems should be seen in connection with his capacity as a sailor, and possibly the different stories he read or heard during his journeys. Kavvadias was familiar with Greek poetry and tradition, nonetheless in this article we focus on influences from non-Greek poets, which together with the descriptions of his distant journeys make Kavvadias’ poems what they are: exotic and fascinating narratives in verse. KEY WORDS: Kavvadias, Baudelaire, Masefield, comparative poetry Introduction From an early age to the end of his life, Kavvadias worked as a sailor, which is precisely why it can be argued that his poetry had been inspired by his numerous travels around the world. -

Author' Graduate Compos of the W Entitled of Moder an MFA Tisch Sc

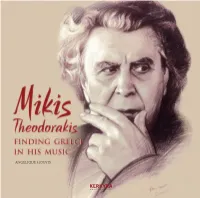

Mikis Theodorakis is a man of many definitions and an inexhaustible supply of talents: poet, musician, composer, MODERN GREEK CULTURE - conductor, political activist, deputy, freedom fighter, exile, partisan, orator and yes, author. Angelique Mouyis’ oeuvre is an important addition to our understanding of his music. And of course, a book about Mikis is also a voyage into modern Greek history and modern Greek culture. Author’s biography ALSO PUBLISHED IN ENGLISH Nick Papandreou, author of Mikis and Manos: A Tale of Two Composers Angelique Mouyis was Coffee Table Books born in Johannesburg, Mikis Theodorakis: My Posters South Africa in 1981 to (bilingual, paperback) Angelique Mouyis has performed a valuable service to the composer and to serious lovers of Greek music by writing about the “other” Theodorakis, a man whose large and impressive body of work in many different Greek-Cypriot parents. In Mikis Theodorakis: My Posters genres deserves better recognition. 2007, under the (bilingual, collector’s edition, supervision of Prof. Jeanne hardcover) Her study is an important contribution to the understanding of Theodorakis’ music, a subject which has MIKIS THEODORAKIS: FINDING GREECE IN HIS MUSIC Zaidel-Rudolph and Prof. Greece Star & Secret Islands been largely neglected by musicologists in his own country, and which deserves to be better known in all its Mary Rörich, she (bilingual) brilliance and abundance by music lovers all over the world. graduated with a Master’s Degree in Music Magical Greece (bilingual, Composition with distinction at the University paperback) Gail Holst-Warhaft, Cornell University of the Witwatersrand, with a research report Magical Greece (bilingual, collector’s edition, hardcover) entitled Mikis Theodorakis and the Articulation A meditation on the perplexity of Greece, the oldest nation but the youngest state, of Modern Greek Identity. -

Modern Greek

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD FACULTY OF MEDIEVAL AND MODERN LANGUAGES Handbook for the Final Honour School in Modern Greek 2020-21 For students who start their FHS course in October 2020 and expect to be taking the FHS examination in Trinity Term 2024 SUB-FACULTY TEACHING STAFF The Sub-Faculty of Byzantine and Modern Greek (the equivalent of a department at other universities) is part of the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages and at present is made up of the following holders of permanent posts: Prof. Marc Lauxtermann (Exeter) 66 St Giles, tel. (2)70483 [email protected] Prof. Dimitris Papanikolaou (St Cross) 47 Wellington Square, tel. (2)70482 [email protected] Dr. Kostas Skordyles (St Peter’s) 47 Wellington Square, tel. (2)70473 [email protected] In addition, the following Faculty Research Fellows, other Faculty members and Emeriti Professors are also attached to the Sub-Faculty and deliver teaching: Prof. Constanze Guthenke Prof. Elizabeth Jeffreys Prof. Peter Mackridge Prof. Michael Jeffreys Dr Sarah Ekdawi Dr Marjolijne Janssen Ms Maria Margaronis 2 FINAL HONOUR SCHOOL DESCRIPTION OF LANGUAGE PAPERS Paper I: Translation into Greek and Essay This paper consists of a prose translation from English into Greek of approximately 250 words and an essay in Greek of about 500-700 words. Classes for this paper will help you to actively use more complex syntactical structures, acquire a richer vocabulary, enhance your command of the written language, and enable you to write clearly and coherently on sophisticated topics. Paper IIA and IIB: Translation from Greek This paper consists of a translation from Greek into English of two texts of about 250 words each. -

How I Came to Translate Karyotakis by Keith Taylor

How I Came to Translate Karyotakis by Keith Taylor Keith Taylor, Univerisity of Michigan faculty member in English and co-winner, along with Prof. Bill Reader of Central Michigan University, of the 2004 Keeley and Sherrard Translation Award discusses the paths he followed on the way to translating the poetry of Kostas Karyotakis It is difficult to follow the paths of imagination and curiosity. But that someone like me-a rather happy protestant from the Canadian prairies-has come to spend a decade or more trying to translate the poems of someone like Kostas Karyotakis-a morose and skeptical Greek who killed himself twenty five years before I was born-is a puzzle that is at least amusing. There are parts to the puzzle that I don't understand and probably never will, but I know that the pieces started falling into place early in my life. My father is a protestant minister from a small and primarily rural denomination and he minored in New Testament Greek in college. Later he spent a couple of decades teaching the basics to the next generation of prairie preachers, so they would all know enough to preach the important sermon on the difference between eros, philos, and agape. The Greek alphabet, a Greek New Testament, and a few dictionaries were always around our house. Of course, I was a rebellious child, and-to my lasting regret- never spent the time to learn even the alphabet from my father, who would have loved to teach it to me. My family moved from western Canada to Indiana when I was a teenager, and for many years I didn't learn to fit in to my new place. -

Tracking the Creative Process of Mikis Theodorakis' Electra

Center for Open Access in Science ▪ https://www.centerprode.com/ojsa.html Open Journal for Studies in Arts, 2020, 3(1), 1-12. ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 ▪ https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojsa.0301.01001k _________________________________________________________________________ Tracking the Creative Process of Mikis Theodorakis’ Electra: An Approach to Philosophical, Esthetical and Musical Sources of his Opera Angeliki Kordellou University of Patras, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Patras, GREECE Department of Theatrical Studies Received: 19 March 2020 ▪ Accepted: 17 May 2020 ▪ Published Online: 28 May 2020 Abstract Taking into consideration Mikis Theodorakis’ autobiography, personal notes, drafts and sketches, several scientific studies about his musical work and by means of an analytical approach of his score for Electra, it seems that tracking its creative process demands a holistic approach including various musical and extra musical parameters. For this reason the aim of this paper is to present an overview of these parameters such as: (a) aspects of the Pythagorean theory of the Universal Harmony which influenced the artist’s worldview and musical creation; (b) the artistic impact of the ancient Greek tragedy and especially of the tragic Chorus on his musical activity; (c) his long term experience in stage music, and particularly music for ancient drama performances; (d) his music for M. Cacoyannis’ movie Electra; (e) the use of musical material deriving from previous compositions of Theodorakis; and (f) the reference to musical elements originating from the Greek musical tradition. Keywords: Electra, Mikis Theodorakis, lyrical tragedy, Greek contemporary music, Greek opera. 1. Introduction The tragic fate of Electra has been the source of artistic expression since antiquity. -

The Dialogic Relationship Between Poems and Paintings and Its Application to Literary Education in High School

The Dialogic Relationship Between Poems and Paintings and its Application to Literary Education in High School La relación dialógica entre poemas y pinturas y su aplicación a la educación literaria en la educación superior La relació dialògica entre poemes i pintures i la seua aplicació a l’educació literària a l’educació superior Marianna Toutziaraki. Phd. Candidate at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece. [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8406-9077 Abstract The purpose of this paper is to discuss the dialogic relationship between literary texts and paintings and the function of painting pictures in the teaching of literature in Secondary Education. The incorporation of paintings into literary education is founded on Bakhtin’s principle of dialogism. The wider spirit of the theory of dialogism allows us to detach the literary text from the solitude of its autonomy, connecting it not only to other literary texts but also to other forms of art, which unfold within a particular historical and cultural context. One example of the dialogic relationship between literature and painting could be the dialogue between the poem ‘We are just some… [battered guitars]’ of the Greek poet Kostas Karyotakis and two paintings of the Austrian artist Egon Schiele, which was deployed in a teaching session for Greek eleventh graders. This sample teaching, thoroughly described in the paper, gave prominence to the dialogic relationship between the poem and the paintings, tracing their analogies on a thematic, stylistic and sociohistorical level. It also brought out the students’ role as active participants in the dialogue between the poem and the paintings and as crucial agents of the meaning- making process. -

Neither Jew Nor Greek, a Memorial for All Gets a $50 Million Gift Athens Remembers the Holocaust – at from the Vagelos’ Long Last

O C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek Americans c v A wEEKly gREEK AmERIcAN PUblIcAtION www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 13, ISSUE 677 October 2-8 , 2010 $1.50 Columbia Med School Neither Jew Nor Greek, A Memorial For All Gets a $50 Million Gift Athens Remembers The Holocaust – At from the Vagelos’ Long Last By Constantine S. Sirigos He is now Chairman of the Board By Sylvia Klimaki TNH Staff Writer of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, TNH Staff Writer Inc. as well as a member of the NEW YORK – Among the most Board of Directors of the Pruden - ATHENS - On a sunny Monday noted philanthropists in Greek tial Insurance Company. A 1955 morning a few months ago, American Society, Roy and Diana graduate of Barnard College, Di - Athens unveiled its first Holo - Vagelos have given their largesse ana Vagelos serves on the Board caust memorial, the last Euro - again, this time a $50 million do - of Trustees of Barnard as vice pean Union capital to commem - nation to Columbia University’s chair of the board and chair of orate its Jewish population that Medical School – his alma mater the Trustee Committee on Cam - was imprisoned and tortured, – to help the noted facility to pus Life. She and Dr. Vagelos and the 65,000 Greek Jews ex - keep producing highly schooled have made generous donations ecuted by the Third Reich. physicians and medical re - to Barnard College and Colum - Greece stood nearly alone in searchers for generations. The bia University Medical Center. -

Gunes Findikoglu Tez Son

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ BATI DİLLERİ ve EDEBİYATLARI ANABİLİM DALI ÇAĞDAŞ YUNAN DİLİ ve EDEBİYATI BİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ YUNAN ŞAİR KOSTAS KARYOTAKİS’İN YAŞAMI, YAPITLARI VE YUNAN ŞİİRİNE ETKİSİ GÜNEŞ FINDIKOĞLU 2501161093 TEZ DANIŞMANI DR. ÖĞR. ÜYESİ İRİNİ SARIOĞLU İSTANBUL – 2020 ÖZ YUNAN ŞAİR KOSTAS KARYOTAKİS’İN YAŞAMI, YAPITLARI ve YUNAN ŞİİRİNE ETKİSİ GÜNEŞ FINDIKOĞLU 19. yüzyılın sonlarında ortaya çıkan sembolizm akımından etkilenerek eserler kaleme alan 1920 Kuşağı şairleri Yunanistan edebiyat tarihi için oldukça önem arz etmektedir. Kısa ömrüne çok sayıda ve nitelikli şiirler sığdırmış olan şair Kostas Karyotakis ise bu edebi kuşağın en önemli temsilcilerinden sayılmaktadır. Türkiye’de konu üzerine yapılmış olan çalışmaların sayısının kısıtlı olması bu çalışmanın yapılmasında önemli bir etkendir. Çalışmada öncelikle Kostas Karyotakis’in yaşadığı dönemin siyasal olayları ve edebi gelişmeleri ele alınarak genel bir tasvir yapılmaya çalışılmış, ardından 32 yıllık yaşamı kronolojik olarak aktarılmıştır. Şairin etkilendiği yerli ve yabancı kaynakların izleri gözlemlendikten sonra ölümünün ardından ortaya çıkan “Karyotakizm” akımının Yunan edebiyatında nasıl bir etki oluşturduğu analiz edilmiştir. Çalışmanın sonunda ise Yunan şairin 22 şiirinin Türkçe çevirisine yer verilmiştir. Anahtar Sözcükler: Yunanistan, Şiir, Sembolizm, 1920 Kuşağı, Kostas Karyotakis iii ABSTRACT LIFE, WORKS AND INFLUENCE ON GREEK POETRY OF GREEK POET KOSTAS KARYOTAKIS GUNES FINDIKOGLU The importance of 1920s poets’, who were influenced by the Symbolism movement that emerged at the end of the 19th century is undeniable for the history of modern Greek literature. The poet Kostas Karyotakis, who has written numerous and qualified poems in his short life, is one of the most significant representatives of this literary generation. The inadequate number of studies conducted on the topic in Turkey is the main cause of the existence of this work. -

The CHARIOTEER an Annual Review of Modern Greek Culture

The CHARIOTEER An Annual Review of Modern Greek Culture NUMBER 14 19 7 2 HOURS OF LIFE a nouvelle by Ange Vlachos EVYTHOS a short story by Andreas Karkavitsas POEMS by aryotakis, Elytis, Vrettakos, Karelli, Sinopoulos, Decavalles, Anagnostakis, Theotoka and W. B. Spanos WOODCUTS by Achilles Droungas BOOK REVIEWS Published by Parnassos, Greek Cultural Society of New York IJ.OO ANT.nNJ-a: aEKABAAAE~ QKEANI~EI IKAPO~ 1970 "I am struck with wonder by the perfection of the form of these poems and by the fine sensibility of the images and thoughts that they emit. I drew great joy from their reading." Takis Papatsonis of the Academy of Athens "The whole collection is held in the same tone, the same deeply moved aware ness of the function of poetry and of the "being" of man, that unspeakable loneliness." George Themelis "[Poems] very Greek. Rich. A scintillation of the potentialities of our lan guage, and a symphony of the grace and joy of sound ... A realm of bril liant forms of speech, which reveals itself' as inexhaustible to the sensitive reader. Words like returning, folding waves, and always multicolored, wet pebbles upon our friendly shores, the mythical ones that build dreams and knowledge and memory, the substance and treasure, of the poet." Zoe Karelli "They are both intimate and strong, and give one a sharp impression of values which I would have found it hard to enunciate, but which are, I suppose, the strongest .part of what is most intimate in the experience of life." Peter Levi, S.J. "A poetry so real and select, which has discovered its true country . -

14 Kostas Karyotakis Kostas Karyotakis (1896-1928) Is Considered by Many Greeks to Be One of Their Most Important Writers Duri

▲ Kostas Karyotakis Kostas Karyotakis (1896-1928) is considered by many Greeks to be one of their most important writers during the years after the First World War and, in particular, after the Greek catastrophe in Asia Minor. He was born in Tripoli in the Peloponnesian peninsula, but spent his childhood in various provincial towns around Greece. After studying law at the University of Athens, he became a civil servant, subject to the whims of his bureaucratic superiors. As a poet, he was influenced by the French symbolists and became the leading Greek example of post- Romantic despair, although his work has a uniquely satirical edge. He published three collections of poems before his suicide in the town of Preveza. The formal precision of his poetry, his dark vision, and his tragic end were enormous influences on later Greek poets. His work has seldom been translated into English. ● 14 karyotakis (p. 14-18) 14 1/27/06, 2:14 PM ■ KOSTAS KARYOTAKIS Joy I hope for flowers even on junipers. The green clearing laughs like my love. The soft pine plays with the sun’s ray. Even graves will smell sweet, like marriage beds. Heartbeat of the forest, a doe darts away. And next to where we had lain wild lilies exude their fragrance and a crimson rose opens, my joy. I see the breeze — it blows in your hair. Your eyes are profound, the road of my life, discovered in April. I no longer feel sorry for the anemone, which our love-wrestling crushes on the ground, as I give myself to the elixir from your lips. -

CP Cavafy Music Resource Guide

C. P. Cavafy Music Resource Guide: Song and Music Settings of Cavafy’s Poetry Researched by Vassilis Lambropoulos Compiled by Peter Vorissis and Artemis Leontis Modern Greek Program & C. P. Cavafy Professorship in Modern Greek Departments of Classical Studies and Comparative Literature University of Michigan Version 2: January 14, 2020 Please send additions and corrections to [email protected] Cavafy Music Resource Guide 1 Cavafy Song Settings: A Music Resource Guide Adamopoulos, Loukas (Αδαμόπουλος, Λουκάς). 1981. «Επέστρεφε» (Come back). Κέρκυρα ’81: Αγώνες ελληνικού τραγουδιού—Τα 30 τραγούδια (Kerkyra ’81: Greek song contest). Αthens: Minos. Setting: «Επέστρεφε» (Come Back). Anabalon, Patricio. 2003. Itaca. Poetas griegas musicalizados. Santiago: Alerce Producciones Fonograficas S.A. Includes the songs “Itaca” (Ithaka), “Regresa” (Come back), “Una Noche/Las Ventanas” (One night / Windows). Anagnostatos, Yiannis (Αναγνωστάτος Γιάννης, also known as Lolek). 2010. «Κεριά». In the compilation Ποιήματα του Κ.Π. Καβάφη (Poems of C.P. Cavafy). Athens: Odos Panos 147 (January–March). (See “Lolek” below). Anestopoulos, Thanos (Ανεστόπουλος, Θάνος). 2001. «Κεριά» (Candles). In Οι ποιητές γυμνοί τραγουδάνε (Poets sing naked). Athens and Patra: Κονσερβοκούτι. For voice and electronic accompaniment or guitar. Composed and sung by Thanos Anestopoulos (Θάνος Ανεστόπουλος) under the pseudonym ΑΣΘΟΝ ΣΑΠΤΟΥΣ ΛΕΟΝΟΣ, an anagram of his name. First released as a cassette by the magazine «Κονσερβοκούτι» (Tin can, the magazine of OEN, Οργάνωση Επαναστατικής Νεολαίας, Organization of Revolutionary Youth). Setting: «Κεριά» (Candles). Angelakis, Manolis (Αγγελάκης, Μανώλης) & τα Θηρία (and the Beasts). 2012. «Απολείπειν ο Θεός Αντώνιον» (The God Abandons Antony). Ο άνθρωπος βόμβα (The bomb man). Patras: Inner Ear. Sung by Manolis Angelakis with rock ensemble.