The Celestial Law1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9575 State St. Sandy, Utah

2019 SALT LAKE SYMPOSIUM THE FUTURE OF FAITH MOUNTAIN AMERICA 9575 State St. JULY 31- EXPO CENTER Sandy, Utah AUG 03 INDEX OF PARTICIPANTS GUIDE TO NUMBERING: WEDNESDAY = 000s, THURSDAY = 100s, FRIDAY = 200s, SATURDAY = 300s ALLRED, JANICE 321 DRAUGHON, KRISTEN 358 KESLER, JOHN 374 PETREY, TAYLOR 111 ALLRED, JOSH 122, 165, 231, EASTMAN, ALAN 242 KESLER, JOHN T. 175 PINBOROUGH, ELIZABETH 127 337, 358 EASTMAN, VICKIE 242 KIMBALL, CHRISTIAN 251 PLATT, MCKAY LYMAN 162 ANDERSON, DEVERY 142 ECCLESTON, MICHAEL 171 KIMBALL, TOM 124, 132, 314 POOL, JERILYN HASSELL 343, ASLAN, REZA 91 FLAMM, BRENT 154, 212 KLEIN, LINDA KAY 291 391 BAIRD, JOSHUA 356 FLAMM, LANEECE 155, 222, KOSKI, JENNIFER 162, 173, 261, POPPLETON, LANDON 365 BAKER, PAULA 166, 331, 377 356 275 PUGLSEY, MARK 373 BARKDULL, NATALIE SHEP- FLORMAN, STEVE 125, 223, LARSEN, JOHN 173 QUINN, D. MICHAEL 233, 273 HERD 121, 136, 163 235, 252 LAURITZEN, RACHAEL 157 RANSOM, DEVEN 272 BARLOW, LISA 171 FOSTER, CRAIG L. 368 LENART, TANNER 171 RASHETA, ANISSA 172 BARNARD, CHELSI 391 FRAZIER, GRANT 275 LIU, TIMOTHY 377 REEL, BILL 355 BARRUS, CLAIR 211, 323, 364 FURR, KELLY 237 LOGAN, AMY 212 REES, BOB 133, 175, 216, 201, BATEMAN, ROMAN 177 GARRETT, JAKE 176 LOPEZ, FRANCHESCA 275 266, 271 BENNET, RICK C. 327 GHNEIM, JABRA 354 MACKAY, LACHLAN 353 REES, GLORIA 133, 374 BENNETT, JIM 213 GOMEZ, BECKY 271, 357, 378 MANDELIN, NATALIE SPERRY RFM 267 BENNETT, RICK C. 218, 225 GONZALEZ, YOSHIMI FEY 227, 131, 226, 322 ROBERTS, ALICE FISHER 336, BENNETT, TOM 122, 215, 324, 268, 314 MARQUARDT, H. MICHAEL 211, 351, 372 265 GREENWELL, ROBERT A. -

Byu Religious Education WINTER 2015 REVIEW

byu religious education WINTER 2015 REVIEW CALENDAR COMMENTS INTERVIEWS & SPOTLIGHTS STUDENT & TEACHER UPDATES BOOKS Keith H. Meservy Off the Beaten Path message from the deans’ office The Blessing of Positive Change B righam Young University’s Religious Studies Center (RSC) turns forty this year. Organized in 1975 by Jeffrey R. Holland, then dean of Religious Instruction, the RSC has been the means of publishing and disseminat- ing some of the best Latter-day Saint scholarship on the Church during the past four decades. The RSC continues to be administered and supported by Religious Education. One notable example of RSC publishing accomplish- ments is the journal Religious Educator. Begun in 2000, this periodical continues to provide insightful articles for students of scripture, doctrine, and quality teaching and learning practices. Gospel teachers in wards and branches around the world as well as those employed in the Church Educational System continue to access this journal through traditional print and online options. Alongside the Religious Educator, important books continue to be published by the RSC. For example, the RSC published the Book of Mormon Symposium Series, which has resulted in nine volumes of studies on this key Restoration scripture (1988–95). Two other important books from 2014 are By Divine Design: Best Practices for Family Success and Happiness and Called to Teach: The Legacy of Karl G. Maeser. For some years now the RSC has also provided research grants to faculty at BYU and elsewhere who are studying a variety of religious topics, texts, and traditions. And the RSC Dissertation Grant helps provide funds for faithful Latter-day Saint students who are writing doctoral dissertations on religious topics. -

Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects by Eugene England

Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects By Eugene England This essay is the culmination of several attempts England made throughout his life to assess the state of Mormon literature and letters. The version below, a slightly revised and updated version of the one that appeared in David J. Whittaker, ed., Mormon Americana: A Guide to Sources and Collections in the United States (Provo, Utah: BYU Studies, 1995), 455–505, is the one that appeared in the tribute issue Irreantum published following England’s death. Originally published in: Irreantum 3, no. 3 (Autumn 2001): 67–93. This, the single most comprehensive essay on the history and theory of Mormon literature, first appeared in 1982 and has been republished and expanded several times in keeping up with developments in Mormon letters and Eugene England’s own thinking. Anyone seriously interested in LDS literature could not do better than to use this visionary and bibliographic essay as their curriculum. 1 ExpEctations MorMonisM hAs bEEn called a “new religious tradition,” in some respects as different from traditional Christianity as the religion of Jesus was from traditional Judaism. 2 its beginnings in appearances by God, Jesus Christ, and ancient prophets to Joseph smith and in the recovery of lost scriptures and the revelation of new ones; its dramatic history of persecution, a literal exodus to a promised land, and the build - ing of an impressive “empire” in the Great basin desert—all this has combined to make Mormons in some ways an ethnic people as well as a religious community. Mormon faith is grounded in literal theophanies, concrete historical experience, and tangible artifacts (including the book of Mormon, the irrigated fields of the Wasatch Front, and the great stone pioneer temples of Utah) in certain ways that make Mormons more like ancient Jews and early Christians and Muslims than, say, baptists or Lutherans. -

Changes in Seniority to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2009 Changes in Seniority to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Travis Q. Mecham Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Mecham, Travis Q., "Changes in Seniority to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints" (2009). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 376. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/376 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHANGES IN SENIORITY TO THE QUORUM OF THE TWELVE APOSTLES OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS by Travis Q. Mecham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: _______________________ _______________________ Philip Barlow Robert Parson Major Professor Committee Member _______________________ _______________________ David Lewis Byron Burnham Committee Member Dean of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2009 ii © 2009 Travis Mecham. All rights reserved. iii ABSTRACT Changes in Seniority to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by Travis Mecham, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2009 Major Professor: Dr. Philip Barlow Department: History A charismatically created organization works to tear down the routine and the norm of everyday society, replacing them with new institutions. -

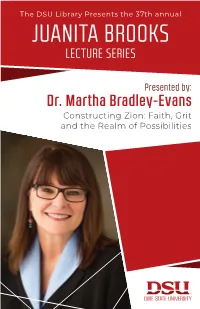

Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

The DSU Library Presents the 37th annual JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES Presented by: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit and the Realm of Possibilities THE JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES PRESENTS THE 37TH ANNUAL LECTURE APRIL 1, 2020 DIXIE STATE UNIVERSITY Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit, and the Realm of Possibilities By: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Copyright 2020, Dixie State University St. George, Utah 84770. All rights reserved 2 3 Juanita Brooks Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author. She is recognized, by scholarly consensus, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been lifelong friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her work through this lecture series. Dixie State University and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner family. 5 the Honorary AIA Award from AIA Utah. In 2014 the Outstanding Achievement Award from the YWCA and was made a fellow of the Utah State Historical Society. She is the past vice chair of the Utah State Board of History, a former chair of the Utah Heritage Foundation. Dr. Bradley’s numerous publications include: Kidnapped from that Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists; The Four Zinas: Mothers and Daughters on the Frontier; Pedastals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority and Equal Rights; Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet, 1839- 1844; Plural Wife: The Autobiography of Mabel Finlayson Allred, and Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet 1839-44 among others. -

July 25-28 Sandy, Utah Mountain America Expo

MOUNTAIN AMERICA EXPO CENTER JULY 25–28 JULY 25-28 SANDY, UTAH MOUNTAIN AMERICA EXPO CENTER INDEX OF PARTICIPANTS GUIDE TO NUMBERING: WEDNESDAY = 000s, THURSDAY = 100s, FRIDAY = 200s, SATURDAY = 300s ADAMS, STIRLING 354 ENGLISH, JONATHON 157, LARSEN, JOHN 364 POOL, JERILYN HASSELL 142, ALEXANDER, THOMAS G. 328, 376 LARSEN, STEPHENIE 326 236, 332, 367 171 ENGLISH, SARAH JOHNSON LAW, ROBBIE 153, 175 POPPLETON, LANDON 166 ALLRED, JANICE 361 176, 316, 357 LEAVITT, PETER 234 PORTER, PERRY 252, 262 ALLRED, JOSH 174, 226 FARR, AMANDA 276 LIND, MINDY STRATFORD 292 POTTER, KELLI D. 233 ANDERSON, DEVERY 171, 374 FIRMAGE, EDWIN B. 314 LINES, KENNETH 164 PRINCE, GREGORY 291 ANDERSON, LAVINA FIELDING FIRMAGE, SARAH E. 314 LINKHART, ROBIN 91 PULIDO, MARTIN 122 171 FORD, GARY 161 LISMAN, STEPHANIE SHUR- QUINN, D. MICHAEL 351 APPLEGATE, KEILANI 214 FREDERICKSON, RON 124 TLIFF 162, 277 REEL, BILL 331, 352 BAKER, JACOB 334 FROST, JAKE 292, 342 LIVESEY, JARED 272 REES, BOB 124, 163, 211, 238, BARLOW, PHIL 377 FULLER, BERT 268, 342 LONG, MATT 366 264, 301, 356, 377 BARNARD, CHELSI 164, 224, FURR, KELLY 232 LUKE, JEANNINE 321 REEVE, W. PAUL 111 336 GALVEZ, SAMY 315 MACKAY, LACHLAN 223, 371 RENSHAW, JERALEE 176 BARRUS, CLAIR 311 GEISNER, JOE 278, 351 MANDELIN, NATALIE SPERRY REX, JIMMY 332 BARRUS, CLAIR 278, 311 GLASSCOCK, RANDY 236 214, 332, 362, 378 RHEES, KELLY 355 BENNETT, APRIL YOUNG 275 GLENN, TYLER 214 MANGELSON, BRITTANY 223 RICHEY, ROSS 132, 224 BENNETT, RICK 271, 377 GREENWELL, ROBERT A. 222 MARQUARDT, H. MICHAEL 311 RIESS, JANA 152, 372 BENNETT, TOM 133, 151 GRIFFITH, JAY 356 MCCLEARY, PATRICK C. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999

Journal of Mormon History Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 1 1999 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1999) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 25 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Table of Contents CONTENTS LETTERS viii ARTICLES • --David Eccles: A Man for His Time Leonard J. Arrington, 1 • --Leonard James Arrington (1917-1999): A Bibliography David J. Whittaker, 11 • --"Remember Me in My Affliction": Louisa Beaman Young and Eliza R. Snow Letters, 1849 Todd Compton, 46 • --"Joseph's Measures": The Continuation of Esoterica by Schismatic Members of the Council of Fifty Matthew S. Moore, 70 • -A LDS International Trio, 1974-97 Kahlile Mehr, 101 VISUAL IMAGES • --Setting the Record Straight Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, 121 ENCOUNTER ESSAY • --What Is Patty Sessions to Me? Donna Toland Smart, 132 REVIEW ESSAY • --A Legacy of the Sesquicentennial: A Selection of Twelve Books Craig S. Smith, 152 REVIEWS 164 --Leonard J. Arrington, Adventures of a Church Historian Paul M. Edwards, 166 --Leonard J. Arrington, Madelyn Cannon Stewart Silver: Poet, Teacher, Homemaker Lavina Fielding Anderson, 169 --Terryl L. -

Emma Hale Smith on the Stage

Emma Hale Smith on the Stage: The One Woman Play By Christopher James Blythe Made possible by a grant from the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts, Art for Uncertain Times For well over a century, Emma Hale Smith was the arch-apostate of the Latter-day Saint imagination. She had betrayed her husband, lied about plural marriage, refused to go West, and encouraged her son to take the lead of a rival church. Fast forward to the late twentieth century and the faithful had thoroughly embraced Smith as a key figure among the early righteous. Emma’s redemption began slowly as Latter-day Saint writers took care to emphasize her contributions to the faith while paying less attention to what had been considered her mistakes. While historians and church leaders paved the way for this reorientation, it was the arts that resurrected and reformed the Elect Lady in the Saints’ imagination. Beginning in the 1970s, there were a series of theatrical performances, multiple works of art, and a handful of popular books devoted to presenting Emma Hale Smith in a kinder light. Thom Duncan’s The Prophet and later Buddy Youngreen’s Yesterday and Forever brought the story of Emma and Joseph’s love affair to the stage in the mid-1970s. These productions were part of what scholar and playwright Mahonri Stewart has called the “‘boom period’ of Mormon drama in the 1970s.”1 In this essay, I turn our attention in a different direction to the burgeoning genre of theatrical monologues – the solo performance. Specifically, I document the one-woman plays that brought audiences face to face with a sympathetic Emma Hale Smith who beckoned for their understanding. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Goodbye I Love You by Carol Lynn Pearson the Overeducated Housewife

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Goodbye I Love You by Carol Lynn Pearson The Overeducated Housewife. Just another boring blog about a boring housewife… Repost: my review of Carol Lynn Pearson’s Goodbye, I Love You… Here’s another reposted Epinions review from May 2008 that I’m trying to save from obscurity. I’m posting it as/is. You never know what will happen in a relationship, even when it seems to be made in heaven… In her 1986 book Goodbye, I Love You , Carol Lynn Pearson explains what it was like for her to be Mormon and married to a gay man. When she met her husband, Gerald Pearson, for the first time, Carol Lynn Pearson thought he “shone”. In warm, glowing terms, Pearson describes the man whose charisma had captivated her at a party she attended back in the spring of 1965. Gerald had been telling a funny story about his days as an Army private, posted at Fort Ord. Carol Lynn Pearson enjoyed the story, and yet she was horrified that the Army had deigned to turn this gentle soul into a killer. Later, Carol Lynn had a conversation with Gerald and discovered that he’d just returned from a two year LDS church mission in Australia and was preparing to finish his college education at Brigham Young University (BYU) in Provo, Utah. Pearson had already earned two degrees at BYU, both in drama. The two had a lot in common besides theatre and religion. As good Mormons, they also felt the pressure to be married, especially since neither of them was getting any younger. -

Brigham Young and Eliza R. Snow

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 40 Issue 2 Article 5 4-1-2001 The Lion and the Lioness: Brigham Young and Eliza R. Snow Jill Mulvay Derr Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Derr, Jill Mulvay (2001) "The Lion and the Lioness: Brigham Young and Eliza R. Snow," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 40 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol40/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Derr: The Lion and the Lioness: Brigham Young and Eliza R. Snow FIG i eliza R snow ca 1868 69 photograph brigham young possibly march 11186911 1869 photo by charles R savage church archives graph by charles R savage courtesy gary and carolynn ellsworth Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2001 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 40, Iss. 2 [2001], Art. 5 the lion and the lioness brigham young and eliza R snow jill mulvay derr he was born in 1801 she in 1804 he was a man known for his humor and gruffnessgruffhess she a woman known for her sobriety and refinement he preached unforgettable sermons though he never learned to spell she wrote reams of poetry and songs he provided her a home as one of his wives for thirty years but she never took his name both he and she were passionately devoted to the prophet joseph smith and his expansive -

Bear River Heritage Area Book

Bear River heritage area Idaho Utah — Julie Hollist Golden Cache Bear Lake Pioneer Spike Valley Country Trails Blessed by Water Worked by Hand The Bear River Heritage Area — Blessed by Water, Worked by Hand fur trade, sixteen rendezvous were held—four in The Bear River those established by more recent immigrants, like Welcome to the Bear what is now the Bear River Heritage Area, and the The head of the Bear River in the Uinta people from Japan, Mexico, Vietnam and more. other twelve within 65 to 200 miles. Cache Valley, Mountains is only about 90 miles from where it Look for cultural markers on the landscape, River Heritage Area! which straddles the Utah-Idaho border (and is ends at the Great Salt Lake to the west. However, like town welcome signs, historic barns and It sits in a dry part of North America, home to Logan, Utah, and Preston, Idaho, among the river makes a large, 500-mile loop through hay stacking machines, clusters of evergreen yet this watershed of the Bear River is others), was named for the mountain man practice three states, providing water, habitat for birds, fish, trees around old cemeteries and town squares of storing (caching) their pelts there. and other animals, irrigation for agriculture and that often contain a church building (like the greener than its surroundings, offering hydroelectric power for homes and businesses. tabernacles in Paris, Idaho; and Brigham City, a hospitable home to wildlife and people Nineteenth Century Immigration Logan, and Wellsville, Utah, and the old Oneida alike. Early Shoshone and Ute Indians, The Oregon Trail brought thousands Reading the Landscape Stake Academy in Preston, Idaho). -

A Lady's Life Among the Mormons

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Exposé of Polygamy: A Lady's Life among the Mormons Fanny Stenhouse Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Stenhouse, T. B. H., & DeSimone, L. W. (2008). Expose ́ of polygamy: A lady's life among the Mormons. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exposé of Polygamy A Lady’s Life among the Mormons Volume 10 Life Writings of Frontier Women Used by permission, Utah State Historical Society, all rights reserved. Fanny Stenhouse. Exposé of Polygamy: A Lady’s Life among the Mormons Fanny Stenhouse Edited by Linda Wilcox DeSimone Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 2008 Copyright © 2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 www.usu.edu/usupress Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper ISBN: 978–0–87421–713–1 (cloth) ISBN: 978–0–87421–714–8 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stenhouse, T. B. H., Mrs., b. 1829. Exposé of polygamy : a lady’s life among the Mormons / Fanny Stenhouse ; edited by Linda Wilcox DeSimone. p. cm. – (Life writings of frontier women ; v. 10) Originally published: New York : American News Co., 1872.