Sivens: the Removal of the French Territory by Means of Planning and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secretaire D'état Aux Petites Et Moyennes Entreprises

ARNAUD MONTEBOURG MINISTRE DU REDRESSEMENT PRODUCTIF AGENDA PRESSE PREVISIONNEL D’ARNAUD MONTEBOURG SEMAINE DU 26 NOVEMBRE AU 2 DECEMBRE Paris, vendredi 23 novembre 2012 N° 224 LUNDI 26 NOVEMBRE 10H30 – 11H30 Entretien avec M. Raphaël DU MERAC, Président de Talents Home 12H00 – 13H00 Entretien avec M. Jean-Bertrand DRUMMEN, Président de la Conférence générale des juges consulaires de France 14H00 – 18H00 Visite de l’entreprise Duralex à La Chapelle Saint-Mesmin (Loiret) 18H00 – 20H30 Intervention d’Arnaud MONTEBOURG dans le cadre de la table ronde organisée par la Fondation Res Publica sur la réindustrialisation, Maison de l’Amérique Latine MARDI 27 NOVEMBRE 9H15 – 13H00 Réunion du 8ème comité d’orientation stratégique des éco-industries, présidée par Arnaud MONTEBOURG et Mme Delphine BATHO, Ministre de l’Ecologie, du Développement durable et de l’Energie, suivie de la visite et de l’inauguration par les deux ministres du Salon International des Equipements, des Technologies et des Services de l’Environnement Pollutec 2012, Lyon 16H30 – 17H00 Intervention d’Arnaud MONTEBOURG dans le cadre du colloque « Les rencontres de l'industrie compétitive, retrouver le chemin de la croissance » organisé par Les Echos 20H30 – 22H30 Rencontre avec l’Association Française des Entreprises Privées, à l’invitation de M. Pierre PRINGUET, Président de l’AFEP MERCREDI 28 NOVEMBRE 9H00 – 9H40 Intervention d’Arnaud MONTEBOURG dans le cadre du colloque organisé par l’Union Française de l’Electricité (UFE) sur la transition énergétique et la politique industrielle, 28 avenue George V Paris 10H00 – 11H30 Conseil des Ministres, Palais de l’Elysée 11H30 – 12H30 Remise des insignes de Grand Croix de l'Ordre National du Mérite au Premier Ministre M. -

Official Journal C 3 of the European Union

Official Journal C 3 of the European Union Volume 62 English edition Information and Notices 7 January 2019 Contents IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2019/C 3/01 Euro exchange rates .............................................................................................................. 1 NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES 2019/C 3/02 Notice inviting proposals for the transfer of an extraction area for hydrocarbon extraction ................ 2 2019/C 3/03 Communication from the Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Policy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands pursuant to Article 3(2) of Directive 94/22/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the conditions for granting and using authorisations for the prospection, exploration and production of hydrocarbons ................................................................................................... 4 V Announcements PROCEDURES RELATING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COMPETITION POLICY European Commission 2019/C 3/04 Prior notification of a concentration (Case M.9148 — Univar/Nexeo) — Candidate case for simplified procedure (1) ........................................................................................................................ 6 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance. OTHER ACTS European Commission 2019/C 3/05 Publication of the amended single document following the approval of a minor amendment pursuant to the second subparagraph of Article 53(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 ............................. -

Les Vins Alexander Krossa Alexander Discovered His Passion for Wine in the Family Vineyard in the 90S

Les Vins Alexander Krossa Alexander discovered his passion for wine in the family vineyard in the 90s. Willing to go further, he created a company dedicated to Languedoc wines. As a real pioneer and visionary, Alexander La Croix des Marchands Krossa combines technical and commercial Cuvée Tradition know-how to the service of partner winegrowers. His philosophy: AOP Gaillac professionalize the relationship with foreign clients mastering the technical Soil: Clay gravel terraces of the processes, selection and blending with his Tarn partners. Varietals: Syrah, Duras, Braucol Vinification: Domaine La Croix des Marchands: Harvested by hand at optimal maturity, destemming and crushing. Traditional vatting (20 This is a place where began a two thousand days). 18 months aging in vats. year old love story between the earth and Early bottling to preserve freshness. the vines. This crossroad of potters in the Gallo-Roman era was called “The Tasting notes: Merchant’s Cross.” The name has remained Beautiful shining color with ruby through the centuries and proves that this sheen. A typical spicy nose. Round place was destined to receive vines. in the mouth with spicy and silky Montans, near the town of Gaillac, was a tannins. Gentle finish with small major center of potteries where amphorae dark fruit flavors. marked with the “Croix des Marchands” symbol were filled with this precious nectar Food pairings: Perfect with dishes and later found as far as Southern Spain with sauces, meats and cheese. and Northern Scotland. Service temperature: 18°C The “Croix des Marchands” vineyard of 69 acres is situated near Montans. “Château Palvié” possesses 49 acres of clay- limestone land in Cahuzac sur Vère. -

Arrêté Cadre Interdépartemental Du Portant Définition D'un Plan D'action Sécheresse Pour Le Sous-Bassin Du Tarn

PRÉFET DU TARN DIRECTION DÉPARTEMENTALE DES TERRITOIRES Service eau, environnement et urbanisme Pôle eau et biodiversité Bureau ressources en eau Arrêté cadre interdépartemental du portant définition d'un plan d'action sécheresse pour le sous-bassin du Tarn Les préfets des départements de l’Aveyron, du Gard, de la Haute-Garonne, de l’Hérault, du Lot, de Lozère, du Tarn, de Tarn-et-Garonne, Vu le code civil et notamment les articles 640 à 645, Vu le code de la santé publique, livre III, Vu le code de l’environnement et notamment les articles L.211-3, L.215-7 à L.215-13, L.432- 5 et R.211-66 à R.211-74, Vu le code pénal et notamment son livre Ier – titre III, Vu le code général des collectivités territoriales, notamment son article L. 2215-1, Vu la loi du 16 octobre 1919 modifiée relative à l'utilisation de l'énergie hydraulique, Vu le décret n° 2004-0374 du 29 avril 2004 relatif aux pouvoirs des Préfets, à l'organisation et à l'action des services de l'Etat dans les régions et les départements, Vu le schéma directeur d'aménagement et de gestion des eaux 2010-2015 du bassin Adour- Garonne approuvé le 1er décembre 2009, Vu l'arrêté cadre interdépartemental du 29 juin 2004 de définition d'un plan d'action sécheresse pour le sous-bassin du Tarn, Vu le plan de gestion des étiages (PGE) du bassin versant du Tarn approuvé le 8 février 2010, Considérant la nécessité d'une cohérence de la gestion des situations de crise au niveau de l'ensemble du bassin Tarn, conformément aux principes de l'article L 211-3 du code de l'environnement. -

GENERAL ELECTIONS in FRANCE 10Th and 17Th June 2012

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN FRANCE 10th and 17th June 2012 European Elections monitor Will the French give a parliamentary majority to François Hollande during the general elections on Corinne Deloy Translated by Helen Levy 10th and 17th June? Five weeks after having elected the President of the Republic, 46 million French citizens are being Analysis called again on 10th and 17th June to renew the National Assembly, the lower chamber of Parlia- 1 month before ment. the poll The parliamentary election includes several new elements. Firstly, it is the first to take place after the electoral re-organisation of January 2010 that involves 285 constituencies. Moreover, French citizens living abroad will elect their MPs for the very first time: 11 constituencies have been espe- cially created for them. Since it was revised on 23rd July 2008, the French Constitution stipulates that there cannot be more than 577 MPs. Candidates must have registered between 14th and 18th May (between 7th and 11th May for the French living abroad). The latter will vote on 3rd June next in the first round, some territories abroad will be called to ballot on 9th and 16th June due to a time difference with the mainland. The official campaign will start on 21st May next. The French Political System sembly at present: - the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP), the party of The Parliament is bicameral, comprising the National former President of the Republic Nicolas Sarkozy, posi- Assembly, the Lower Chamber, with 577 MPs elected tioned on the right of the political scale has 313 seats; by direct universal suffrage for 5 years and the Senate, – the Socialist Party (PS) the party of the new Head the Upper Chamber, 348 members of whom are ap- of State, François Hollande, positioned on the left has pointed for 6 six years by indirect universal suffrage. -

Dourgne Sacré Champion Du Tarn

Numéro 33 – Mai 2012 Dourgne sacré Champion du Tarn Magazine d’information édité par le District du Tarn de Football Responsable de la publication : Commission Communication Rédacteur : Franck FERNANDEZ Crédit photo : DTF – Louis GOULESQUE Collaborateurs: Sébastien Bosc, David Welferinger, Sonia Lagasse, Romain Bortolotto. 1 SOMMAIRE AGENDA Page 2 : Agenda Samedi 26 mai à Rigaud Finale du Challenge Trouche à 14h Page 3-4 : Actualité Lescure 3 – Fréjeville Les distinctions individuelles en Excellence Finale du Challenge Manens à 17h Albi Mahorais – Sorèze Page 5 : Tournoi Le Trophée Alain Bénédet – Valence OF Finale de la Coupe du Tarn à 20h Marssac 2 - Dourgne Page 6 : Portrait Laurie et Romain Cabanel - Lacaune Dimanche 3 juin Finale de la Coupe du Midi féminines Page 7 : Football féminin Asptt Albi 2 – TFC2 Les classements Finale du Challenge Souchon Page 8 : Football d’animation Gaillac – St Jean SO St Amans Samedi 16 juin Page 9 : l’ITW décalé Assemblée Générale d’été - Lavaur Mathieu Baudoui – ES Viviers Pages 10-11 : Technique Perfectionnement aux techniques de conduites, dribbles et contrôles pour éliminer un adversaire. CHALLENGE DU JEUNE EDUCATEUR Le District du Tarn de Football organise pour la 5e année consécutive le Challenge du Jeune Educateur. Vous Le soualais Dauer (en-haut) termine meilleur buteur en pouvez télécharger le dossier de Excellence pour la seconde fois consécutive devant le candidature ainsi que le règlement du marssacois André (ci-dessous). Challenge sur le site Internet du DTF. Cette opération a pour but de donner un coup de projecteur sur des jeunes (filles ou garçons) âgés entre 15 et 20 ans qui ont fait le choix de donner de leur temps libre au football en encadrant des équipes lors des entraînements et/ou des rencontres du samedi. -

Action Institutionnelle

Service des droits des femmes et de l’égalité entre les femmes et les hommes Synthèse de l’actualité 18 mai 2012 Action institutionnelle Le président de la République a nommé un gouvernement paritaire Le président de la République, François HOLLANDE, a nommé, le mercredi 16 mai 2012, les membres du nouveau Gouvernement sur la proposition du Premier ministre, Jean‐Marc AYRAULT. La composition du Gouvernement a été annoncée par Pierre‐René LEMAS, Secrétaire général de la présidence de la République. S’il marque le retour d'un ministère chargé de l’égalité entre les femmes et les hommes de plein exercice, le nouveau gouvernement est aussi le premier gouvernement paritaire de l'histoire politique française. Dix‐sept femmes sont en effet nommées sur les trente‐quatre membres du nouveau gouvernement, une « promesse tenue » soulignée par l’ensemble des médias. Les gouvernements de François FILLON nommés en mai et juin 2007 avaient été qualifiés de « paritaire » dans la presse (synthèse du 21 mai et 28 juin 2007). Avec sept femmes ministres sur quinze le premier gouvernement était de fait le plus féminisé de la Ve République, mais les observatrices féministes notaient déjà une régression en juin avec onze femmes et vingt‐deux hommes sur trente‐trois membres, et surtout l’absence d’un ministère en charge des droits des femmes et de l’égalité entre les femmes et les hommes. (Photo © Présidence de la République ‐ P. SEGRETTE). Najat VALLAUD‐BELKACEM, ministre des Droits des femmes, porte‐parole du Gouvernement « La création d’un ministère des droits des femmes est la première étape d’une politique que je souhaite ambitieuse et qui, à mon sens, doit être au cœur du projet de société de la gauche, que je veux porter » écrivait François HOLLANDE dans « Garantir les droits des femmes et transformer la société vers plus d’égalité ‐ 40 engagements pour l'égalité femmes‐ hommes » (synthèse du 11 mai). -

Dialogue N°27

État civil du 1er mai 2016 au 31 octobre 2016 Naissance Léopold CARDON né le 11 mai 2016 à LAVAUR Juliette NGUYEN née le 2 juin 2016 à ALBI Robin ALBERT né le 6 juin 2016 à TOULOUSE Ahausiolésio TALALUA RENAULT né le 20 juillet 2016 à ALBI Jules JIMENEZ né le 24 août 2016 à ALBI Morgane RODRIGUEZ née le 22 septembre 2016 à ALBI Andrea CHEREAU né le 22 octobre 2016 à ALBI Félicitations aux heureux parents et bienvenue à tous ces petits Montanais à qui nous souhaitons tout le bonheur possible. Mariage Lydie VERGNES et Frédéric BRUN le 18 juin 2016 Virginie DUCROCQ et Frédéric KOPACZ le 2 juillet 2016 Julie FOULQUIER et Julien CROUZET le 20 août 2016 Tous nos vœux de bonheur aux mariés. Déceès Joël HOUDAYER décédé le 12 mai 2016 à TOULOUSE André RODIERE décédé le 3 juin 2016 à ALBI Francette ICHER décédée le 15 juin 2016 à TOULOUSE Georgette BÉZIOS décédée le 29 juin 2016 à MONTANS Louisa ROQUES décédée le 8 juillet 2016 à MONTANS Fatma BADJI décédée le 8 juillet 2016 à GAILLAC Lydia GIRARD décédée le 21 juillet 2016 à MONTANS Arnaud BONNEVILLE décédé le 15 août 2016 à ALBI Nous renouvelons aux familles nos plus sincères condoléances 2 était il y a déjà 25 ans, en novembre 1992, que notre Communauté de Com- munes Tarn et Dadou fut créée. A l’époque, elle paraissait déjà immense avec C’ses 29 communes, aujourd’hui au 1er janvier 2017, elle va fusionner avec deux Communautés de Communes voisines, Vère-Grésigne et Cora, ce qui porte le nombre à 63 communes et 70 000 habitants. -

Sentier Autour De L'eau

m o c . s e d i t s a b - e l b o n g i v - e m s i r u o t . w w w ARN téléchargeables sur : sur téléchargeables ARN T RANDO ches fi Autres i n f o @ r a n d o - t a r n . c o m w w w . r a n d o n n e e - t a r n . c o m 05 63 47 73 06 73 47 63 05 T . él : : 14 , rue Timbal - Hôtel Reynès 81000 81000 Reynès Hôtel - Timbal rue ALBI Montans, sur la place du village ! village du place la sur Montans, DESTINATIONS TARNAISES - ESPACE RANDO ESPACE - TARNAISES DESTINATIONS allez faire un tour à l’archéosite de l’archéosite à tour un faire allez les trésors archéologiques de l’époque, de archéologiques trésors les e e e d d s s e e r r u u t t c c u u r r t t s s a a r r f f n n i i s s e e s s u u e e r r b b m m o o n n info e e d d @gaillac-bastides.com r r u u o o j j Pour en savoir plus et découvrir et plus savoir en Pour T é l . : 08 05 40 08 28 28 08 40 05 08 : . (gratuit) décorées était connue dans tout l’empire. tout dans connue était décorées 8 1 3 1 0 - L I S L E S U R T A R N production de poteries moulées et et moulées poteries de production P l a c e P a u l S a i s s a c turel a n trimoine a P Lors de la période gallo-romaine la gallo-romaine période la de Lors A c c u e i l d e L i s l e s u r T a r n ville à fort rayonnement commercial. -

Restauration Du Tescou Et Tescounet

Restauration du Tescou et Tescounet Le mot du Président Créé en 2007, notre syndicat est enfin entré dans sa phase active avec une première tranche de travaux réalisée en 2009/2010 sur les départements du Tarn et du Tarn et Garonne. Ces premiers travaux, un baptême pour notre syndicat, se sont bien passés et ont donnés de bons résultats, cela grâce aux entreprises mais aussi à vous propriétaires. Il s’agit maintenant d’entretenir ces zones déboisées afin d’éviter des repousses importantes et indésirables. Je compte sur votre civilité et votre amour de la nature pour cela. La deuxième tranche de travaux s’est déroulée en début 2011 (janvier-mars) sur les deux départements et nous conti- nuerons tous les ans jusqu’à l’accomplissement final de notre mission. Je remercie une nouvelle fois les Conseils Généraux des trois départements Tarn, Tarn et Garonne et Haute-Garonne ainsi que l’Agence de l’Eau Adour-Garonne et le Conseil Régional Midi-Pyrénées de nous suivre et de nous aider dans ces travaux. J.C. BOURGEADE, Président du Syndicat Mixte du Tescou et Tescou- La réalisation des travaux de restauration du Tescou et du Tescounet Réalisés dans le cadre d'un programme pluriannuel, les travaux de restauration intègrent un ordre de priorité et les spécificités des différents tronçons pour faire face aux besoins les plus pressants. Chaque année, ils sont confiés à des entreprises spécialisées dans le cadre d’un marché public de travaux et visent à une amélioration de l’état général de la rivière. Ils consistent en un rattrapage du cours d’eau après des années d’abandon et font appel à des techniques forestières et de génie végétal (coupe sélective, recépage, élagage, gestion des embâcles…). -

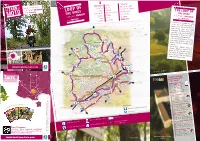

Loop of the Vines Couffouleux St

THETARN BY Loop of the vines i n between vineyard and forests MOTO Rabastens Mauriac Campagnac LOOP OF Couffouleux Broze Forêt de la Grésigne THE VINES Loupiac Montels St. Martin de l’Espinas in between vineyard Lisle-sur-Tarn Cahuzac-sur-Vère Forêt de Sivens Montans Andillac Les Barrières and forests w Gaillac Vieux Salvagnac THE LOOP OF Senouillac Le Verdier Rabastens THE VINES in between vineyard and forests In between the lowland, the valley of the Tarn and the vineyard of Gaillac on the side of the hills, this loop crosses some very varied landscapes. It follows mainly some calm little roads and it will enlight the tourists of bikers who like to alternate visits and wild nature. Lots of sites invite to a break : browse in the historic heart of a town in red bricks, to admire an old church, visit a winery… env. 140 km Among these multiple places to discover : Rabastens, Lisle-sur-Tarn, www.tourisme-tarn.com Gaillac and the vineyard of Gaillac, the forests of Grésigne and Sivens who in Autumn offer the surprising show of the Roaring Stags. Vineyard - Andillac TOURIST OFFICES & information desk on the circuit Bastides & Vignoble du Gaillac - 81600 ( catégorie II ) Office de tourisme de Pays Abbaye Saint-Michel - Gaillac in local tourist offi e circuits ces : Tel.: +33 (0)5 63 57 14 65 all th Find [email protected] www.tourisme-vignoble-bastides.com Avec Créations,Vent d’Autan - Phovoir. / Office of Rabastens - 81800 Hôtel de la Fite TM 2, rue Amédée de Clausade Tel.: +33 (0)5 63 40 65 65 Follow us : [email protected] www.tourisme-vignoble-bastides.com www.facebook.com/tarntourisme.sudouest Office of Lisle-sur-tarn - 81310 TM RoadTrip, D.Viet / CRTMP, J.L. -

Le Nouveau Plan De Gestion Du Tescou Et Du Tescounet : 2019-2024

Travaux envisagés Le nouveau Plan de Gestion du Tescou Actions sur les zones humides Recensement et du Tescounet : 2019-2024 Gestion/Restauration Sensibilisation Zones humides fonctionnelles présentes sur le bassin versant du Tescou Autres actions sur les cours d’eau Le mot du Président Chantiers pilotes de restitution de débit sur 2 retenues J.C. BOURGEADE, Contrôle des points d’accès du bétail : mise en défens, points d’abreuve Président du Syndicat Mixte du Tescou et Tescounet. ment stabilisés ou en retrait du cours d’eau Mise en défens et point d’abreuvement Un nouveau petit journal pour notre syndicat. hors cours d’eau (bassin Cérou-Vère) Nous avons accueilli un nouveau technicien, M Yann LAURENT depuis presque 3 ans maintenant. A ce jour, nous Sensibilisation et communication autour de nos actions avons pratiquement travaillé sur la totalité des rivières Tescou et Tescounet et je dois remercier les propriétai- res riverains, les agriculteurs car ces travaux se sont déroulés dans de bonnes conditions. Le mot du riverain J’ai pu apprécier tout au long de ces travaux la participation des riverains avec les entreprises et le Syndicat. Propriétaires d'un moulin qui enjambe le Tescou sur la commune de LISLE SUR TARN , nous jouissons d'un cadre de vie agréable qui nous impose, à juste titre, des responsabilités quant à la vie de la rivière. Lancés Nous engageons un nouveau Plan Pluriannuel de Gestion, très ambitieux, se conformant aux nouvelle normes et lois depuis peu dans la restauration de notre ancien moulin nous nous devons de respecter les règles environne- sur le domaine des milieux aquatiques.