Unconventional Wisdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

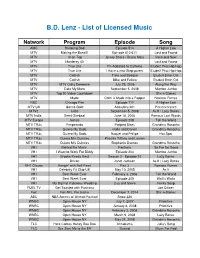

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

Constructions of Deviance and the Performance Of

“WHAT DON’T BLACK GIRLS DO?” : CONSTRUCTIONS OF DEVIANCE AND THE PERFORMANCE OF BLACK FEMALE SEXUALITY by KIARA M. T. HILL JENNIFER SHOAFF, COMMITTEE CHAIR UTZ MCKNIGHT RACHEL RAIMIST A THESIS In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Gender and Race Studies in the Graduate School of the University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2015 Copyright Kiara Monique Hill 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This research interrogates the ways in which Black women process and negotiate their sexual identities. By connecting the historical exploitation of Black female bodies to the way Black female deviant identities are manufactured and consumed currently, I was able to show not only the evolution of Black women’s attitudes towards sexuality, but also the ways in which these attitudes manifest when policing deviancy amongst each other. Chapter 1 gives historical insight to the way that deviancy has been inextricably linked to the construction of Blackness. Using the Post-Reconstruction Era as my point of entry, I demonstrate the ways in which Black bodies were stigmatized as sexually deviant, and how the use of Black caricatures buttressed the consumption of this narrative by whites. I explain how countering this narrative became fundamental to the evolution of Black female sexual politics, and how ultimately bodily agency was later restored through sexual deviancy. Chapter 2 interrogates the way “authenticity” is propagated within the genre of reality TV. Black women are expected to perform deviant identities that coincide with controlling images so that the “authenticity” of Black womanhood is consumed by mainstream audiences. -

Egister Volume Lxix, No

EGISTER VOLUME LXIX, NO. 30. EED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, JANXTARY .16, 1947 SECTION ONE—PAGES 1. TO The Register Again Red Bank Savings Father And Daughter ^acred Concert Monmouth PaYk Gets Heads The List Killed By Train Triplets, All Boys, ] A sample check up'.of 49 of the And Loan Ass'n Word, has been received of the Sunday Night In better weekly newspapers of the sudden passing of Worth Rhodes June 19 -July 30 Date nation, all members of the Audit Has Good Year Bushnell, 42, and his soven-year-old For Episcopal Rector Bureau of Circulation and the daughter Parmly of Mendenhall, Methodist Church Greater Weeklies division of the Pa., who were instantly killed Sat- American Press association, shows Statement By Its urday, January 4, near their home. Elizabeth Waddell Local-Track Is In Excellent Shape— that the average of this group .ran Mr. Busnell and his daughter were Rev. And Mrs. Spofford, Jr., 6,117 lines of national advertising President Offered To in their car and stopped at a cross- Of Fair Haven Is during November. They ranged ing to allow a train to go by. just Are The Proud Parents • . Racing Commission Issues Schedule torn a high of 20,207 lines to a low Tho Public as the train approached tho cross- Soloist Of Evening of 1,358 lines. ing the Bushnell car suddenly •+• Timothy Spofford, 15-montl Monmouth Park will. open its It is pleasing to the publisher Assets of the Red Bank Sayings sprang ahc^d right In front of the A sacred concert sponsored , by son of Rev. -

Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-2-2017 On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy Evan Nave Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Nave, Evan, "On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 697. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/697 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON MY GRIND: FREESTYLE RAP PRACTICES IN EXPERIMENTAL CREATIVE WRITING AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY Evan Nave 312 Pages My work is always necessarily two-headed. Double-voiced. Call-and-response at once. Paranoid self-talk as dichotomous monologue to move the crowd. Part of this has to do with the deep cuts and scratches in my mind. Recorded and remixed across DNA double helixes. Structurally split. Generationally divided. A style and family history built on breaking down. Evidence of how ill I am. And then there’s the matter of skin. The material concerns of cultural cross-fertilization. Itching to plant seeds where the grass is always greener. Color collaborations and appropriations. Writing white/out with black art ink. Distinctions dangerously hidden behind backbeats or shamelessly displayed front and center for familiar-feeling consumption. -

A History of Morgan County, Utah Centennial County History Series

610 square miles, more than 90 percent of which is privately owned. Situated within the Wasatch Mountains, its boundaries defined by mountain ridges, Morgan Countyhas been celebrated for its alpine setting. Weber Can- yon and the Weber River traverse the fertile Morgan Valley; and it was the lush vegetation of the pristine valley that prompted the first white settlers in 1855 to carve a road to it through Devils Gate in lower Weber Canyon. Morgan has a rich historical legacy. It has served as a corridor in the West, used by both Native Americans and early trappers. Indian tribes often camped in the valley, even long after it was settled by Mormon pioneers. The southern part of the county was part of the famed Hastings Cutoff, made notorious by the Donner party but also used by Mormon pioneers, Johnston's Army, California gold seekers, and other early travelers. Morgan is still part of main routes of traffic, including the railroad and utility lines that provide service throughout the West. Long known as an agricultural county, the area now also serves residents who commute to employment in Wasatch Front cities. Two state parks-Lost Creek Reservoir and East A HISTORY OF Morgan COUY~Y Linda M. Smith 1999 Utah State Historical Society Morgan County Commission Copyright O 1999 by Morgan County Commission All rights reserved ISBN 0-913738-36-0 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 98-61320 Map by Automated Geographic Reference Center-State of Utah Printed in the United States of America Utah State Historical Society 300 Rio Grande Salt Lake City, Utah 84 101 - 1182 Dedicated to Joseph H. -

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/4/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 Am 7:30 8 Am 8:30 9 Am 9:30 10 Am 10:30 11 Am 11:30 12 Pm 12:30 2 CBS Football New York Jets at Miami Dolphins

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/4/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS Football New York Jets at Miami Dolphins. (6:30) (N) Å NFL Paid Program Tunnel to Towers Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Cycling Presidents Action Sports (N) Å Volleyball Auto Racing 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife Women’s Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Buffalo Bills. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Igby Goes Down ››› 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Cooking Pépin Baking Lidia 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Orphans of the Genocide 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bob Show Bob Show Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY) The Karate Kid ››› 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program The Sorcerer’s Apprentice ›› (2010) (PG) Hook ››› (1991, Fantasía) Dustin Hoffman, Robin Williams. -

1 United States District Court for The

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ________________________________________ ) VIACOM INTERNATIONAL INC., ) COMEDY PARTNERS, ) COUNTRY MUSIC TELEVISION, INC., ) PARAMOUNT PICTURES ) Case No. 1:07-CV-02103-LLS CORPORATION, ) (Related Case No. 1:07-CV-03582-LLS) and BLACK ENTERTAINMENT ) TELEVISION LLC, ) DECLARATION OF WARREN ) SOLOW IN SUPPORT OF Plaintiffs, ) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR v. ) PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT ) YOUTUBE, INC., YOUTUBE, LLC, and ) GOOGLE INC., ) Defendants. ) ________________________________________ ) I, WARREN SOLOW, declare as follows: 1. I am the Vice President of Information and Knowledge Management at Viacom Inc. I have worked at Viacom Inc. since May 2000, when I was joined the company as Director of Litigation Support. I make this declaration in support of Viacom’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment on Liability and Inapplicability of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act Safe Harbor Defense. I make this declaration on personal knowledge, except where otherwise noted herein. Ownership of Works in Suit 2. The named plaintiffs (“Viacom”) create and acquire exclusive rights in copyrighted audiovisual works, including motion pictures and television programming. 1 3. Viacom distributes programs and motion pictures through various outlets, including cable and satellite services, movie theaters, home entertainment products (such as DVDs and Blu-Ray discs) and digital platforms. 4. Viacom owns many of the world’s best known entertainment brands, including Paramount Pictures, MTV, BET, VH1, CMT, Nickelodeon, Comedy Central, and SpikeTV. 5. Viacom’s thousands of copyrighted works include the following famous movies: Braveheart, Gladiator, The Godfather, Forrest Gump, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Top Gun, Grease, Iron Man, and Star Trek. -

Volume 50 • Number 3 • May 2009

VOLUME 50 • NUMBER 3 2009 • MAY Feedback [ [FEEDBACK ARTICLE ] ] May 2009 (Vol. 50, No. 3) Feedback is an electronic journal scheduled for posting six times a year at www.beaweb.org by the Broadcast Education Association. As an electronic journal, Feedback publishes (1) articles or essays— especially those of pedagogical value—on any aspect of electronic media: (2) responsive essays—especially industry analysis and those reacting to issues and concerns raised by previous Feedback articles and essays; (3) scholarly papers: (4) reviews of books, video, audio, film and web resources and other instructional materials; and (5) official announcements of the BEA and news from BEA Districts and Interest Divisions. Feedback is editor-reviewed journal. All communication regarding business, membership questions, information about past issues of Feedback and changes of address should be sent to the Executive Director, 1771 N. Street NW, Washington D.C. 20036. SUBMISSION GUIDELINES 1. Submit an electronic version of the complete manuscript with references and charts in Microsoft Word along with graphs, audio/video and other graphic attachments to the editor. Retain a hard copy for refer- ence. 2. Please double-space the manuscript. Use the 5th edition of the American Psychological Association (APA) style manual. 3. Articles are limited to 3,000 words or less, and essays to 1,500 words or less. 4. All authors must provide the following information: name, employer, professional rank and/or title, complete mailing address, telephone and fax numbers, email address, and whether the writing has been presented at a prior venue. 5. If editorial suggestions are made and the author(s) agree to the changes, such changes should be submitted by email as a Microsoft Word document to the editor. -

Toward a Poetics of Animality: Hofmannsthal, Rilke, Pirandello, Kafka

Toward a Poetics of Animality: Hofmannsthal, Rilke, Pirandello, Kafka Kári Driscoll Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Kári Driscoll All rights reserved Abstract Toward a Poetics of Animality: Hofmannsthal, Rilke, Pirandello, Kafka Kári Driscoll Toward a Poetics of Animality is a study of the place and function of animals in the works of four major modernist authors: Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Rainer Maria Ril- ke, Luigi Pirandello, and Franz Kafka. Through a series of close readings of canonical as well as lesser-known texts, I show how the so-called “Sprachkrise”—the crisis of language and representation that dominated European literature around 1900—was inextricably bound up with an attendant crisis of anthropocentrism and of man’s rela- tionship to the animal. Since antiquity, man has been defined as the animal that has language; hence a crisis of language necessarily called into question the assumption of human superiority and the strict division between humans and animals on the ba- sis of language. Furthermore, in response to author and critic John Berger’s provoca- tive suggestion that “the first metaphor was animal,” I explore the essential and constantly reaffirmed link between animals and metaphorical language. The implica- tion is that the poetic imagination and the problem of representation have always on some level been bound up with the figure of the animal. Thus, the ‘poetics of animal- ity’ I identify in the authors under examination gestures toward the origin of poetry and figurative language as such. -

Mount Dragon

Mount Dragon by Douglas Preston, 1956– Co-Author Lincoln Child Published: 1996 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Dedication Introduction & PART I … PART II … PART III … Epilogue * * * * * Mount Dragon is a work of fiction. The GeneDyne corporation, the Foundation for Genetic Policy, the Holocaust Memorial Fund, the Holocaust Research Foundation, Hemocyl, PurBlood, X-FLU— and, of course, Mount Dragon itself—are all products of the authors’ imaginations. Any resemblance of these or other entities in the novel to existing entities is purely coincidental. All characters and events portrayed herein are fictitious. Nothing should be interpreted as expressing the policies or depicting the procedures of any corporation, institution, university, or governmental department or agency. J J J J J I I I I I To Jerome Preston, Senior —D. P. To Luchie; my parents; and Nina Soller —L. C. Our symbols shout at the universe, They fly off, like hunters’ arrows Into the night sky. Or knapped spearpoints into flesh. They race like fires across plains, Driving buffalo. —Franklin Butt One window upon Apocalypse is more than enough. —Susan Wright/Robert L. Sinsheimer, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists Introduction The sounds drifted over the long green lawn, so faint they could have been the crying of ravens in the nearby wood, or the distant braying of a mule on the farm across the brown river. The peace of the spring morning was almost undisturbed. One had to listen carefully to the sounds to make certain they were screams. The massive bulk of Featherwood Park’s administrative building lay half-hidden beneath ancient cottonwood trees. -

The Tailor of Panama

The Tailor of Panama by John Le Carré, 1931– Published: 1963 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Dedication & Chapter 1 … thru … Chapter 24 Acknowledgements * * * * * This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. J J J J J I I I I I In memory of Rainer Heumann, literary agent, gentleman, and friend „Quel Panama! “(1) Chapter 1 It was a perfectly ordinary Friday afternoon in tropical Panama until Andrew Osnard barged into Harry Pendel’s shop asking to be measured for a suit. When he barged in, Pendel was one person. By the time he barged out again Pendel was another. Total time elapsed: seventy-seven minutes according to the mahogany- cased clock by Samuel Collier of Eccles, one of the many historic features of the house of Pendel & Braithwaite Co. Limitada, Tailors to Royalty, formerly of Savile Row, London, and presently of the Vía España, Panama City. Or just off it. As near to the España as made no difference. And P & B for short. The day began prompt at six, when Pendel woke with a jolt to the din of band saws and building work and traffic in the valley and the sturdy male voice of Armed Forces Radio. “I wasn’t there, it was two other blokes, she hit me first, and it was with her consent, Your Honour,” he informed the morning, because he had a sense of impending punishment but couldn’t place it. -

The FCC and Reality Television Briana N

S avannah Law Review VOLUME 5 │ NUMBER 1 The False Reality of the African American Culture: The FCC and Reality Television Briana N. Tookes* Abstract Television is the gateway of communication across the world, as it projects the news, educational information, and entertainment for viewers. However, television gives false perceptions about the realities of the world, especially pertaining to different cultures, such as the African American culture. Since the beginning of television, the perception of African Americans and their culture has continued to be displayed under a false light: a demeaning light that gives viewers skewed perceptions about the truths of the African American community. Today, reality television itself plays a huge role in creating this “false reality” of the lives of African Americans in the entertainment world or the pathway for an African American to be successful in America. These issues partly rise from television regulation (or the lack thereof) and how past and current regulation has led to the continuous exploitation of African American culture in reality television. This Note will call out the real issues of reality television, and show that television regulation is needed in areas where the public’s interest is protected, show that content regulation laws should be reevaluated, and show that extending game show regulation to reality television regulation may prevent exploitation. Also, a change in reality television would be impactful if African American participants did not allow themselves to be subject to images that degrade themselves to be aired to the public eye, which not only affects them, but also the entire African American culture as well.