The Color of Odors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A to Z Glossary of Wine Terms

A to Z Glossary of Wine Terms A ABV (Alcohol by Volume) - A measure of the alcohol concentration of a wine, usually expressed as a percentage. Acidic - A tart, sour, or fresh feeling in the mouth when you taste the wine. Aeration - Adding oxygen to the wine to soften tannins. Aggressive – Wine tasting term describing a wine that is either too tannic, too acidic, or a combina- tion of both. Alcohol - Ethanol; in wine it is produced via fermentation with yeast and sugar. Alcoholic – Wine tasting term indicating high alcohol. A wine with a noticeably high alcohol con- tent; perceived as a hotness in the wine. Angular – Wine tasting term used to describe young wines that display predominately sharp, bitter, or tart flavor characteristics. AOC (Appellation d’origine contrôlée) - A term in the French wine designation system which means “controlled designation of origin.” It identifies the location or region where a wine is made. Appearance - In general, the term appearance is used to describe the clarity of a wine. Appellation - A designated wine growing area governed by specific rules regarding the wine grapes grown and wine produced in the specific appellation areas. Aroma - A wine’s scent characteristics; very closely tied in with the flavors. Aromatic - Varieties of grapes that have especially noticeable aromas. Some aromatic grapes in- clude Viognier, Torrontés, Gewürztraminer, Riesling, Muscat, and Pinot Gris. Aromatized – A wine that is infused with botanicals. Vermouth is an aromatized wine. Assemblage - A method of blending wine before bottling. Astringent – A wine tasting term meaning the wine leaves the mouth feeling overwhelmingly dry. -

Phenolic Compounds As Markers of Wine Quality and Authenticity

foods Review Phenolic Compounds as Markers of Wine Quality and Authenticity Vakare˙ Merkyte˙ 1,2 , Edoardo Longo 1,2,* , Giulia Windisch 1,2 and Emanuele Boselli 1,2 1 Faculty of Science and Technology, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Piazza Università 5, 39100 Bozen-Bolzano, Italy; [email protected] (V.M.); [email protected] (G.W.); [email protected] (E.B.) 2 Oenolab, NOI Techpark South Tyrol, Via A. Volta 13B, 39100 Bozen-Bolzano, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0471-017691 Received: 29 October 2020; Accepted: 28 November 2020; Published: 1 December 2020 Abstract: Targeted and untargeted determinations are being currently applied to different classes of natural phenolics to develop an integrated approach aimed at ensuring compliance to regulatory prescriptions related to specific quality parameters of wine production. The regulations are particularly severe for wine and include various aspects of the viticulture practices and winemaking techniques. Nevertheless, the use of phenolic profiles for quality control is still fragmented and incomplete, even if they are a promising tool for quality evaluation. Only a few methods have been already validated and widely applied, and an integrated approach is in fact still missing because of the complex dependence of the chemical profile of wine on many viticultural and enological factors, which have not been clarified yet. For example, there is a lack of studies about the phenolic composition in relation to the wine authenticity of white and especially rosé wines. This review is a bibliographic account on the approaches based on phenolic species that have been developed for the evaluation of wine quality and frauds, from the grape varieties (of V. -

Irrigation and Leaf Removal Effects on Polyphenolic Content of Grapes and Wines Produced from Cv

Available online: www.notulaebotanicae.ro Print ISSN 0255-965X; Electronic 1842-4309 Not Bot Horti Agrobo, 2016, 44(1):133-139. DOI:10.15835/nbha44110254 Original Article Irrigation and Leaf Removal Effects on Polyphenolic Content of Grapes and Wines Produced from cv. ‘Agiorgitiko’ (Vitis vinifera L.) Evangelia CHORTI1, Maria KYRALEOU2, Stamatina KALLITHRAKA2, Manolis PAVLIDIS2, Stefanos KOUNDOURAS3, Ioannis KANAKIS4, Yorgos KOTSERIDIS2* 1Cooperative Winery of Nemea, 130 Papaconstantinou av., 20500 Nemea, Greece; [email protected] 2Agricultural University of Athens, Department of Food Science & Technology, 75 Iera Odos, 11855 Athens, Greece ; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] (*corresponding author) 3Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of Agriculture, Laboratory of Viticulture, 54124, Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] 4Fassoulis Grapevine Nurseries, 20500 Leontio - Nemea, Greece; [email protected] Abstract Vitis vinifera L. cv. ‘Agiorgitiko’ is one of the most important red grape varieties of Greece, cultivated almost exclusively in the region of Nemea in north-eastern Peloponnese. This work aimed to study the influence of some commonly applied viticultural practices on the polyphenolic composition of ‘Agiorgitiko’. Leaf removal at veraison, irrigation, and a combination of both, were applied and the phenolic content of the grapes and of the produced wines was compared. The results showed that leaf removal decreased berry size, enhanced total anthocyanin, total phenol and malvidin 3-O-monoglucoside accumulation in skins and increased the amount of extractable anthocyanins in the juice. The combination of irrigation and leaf removal caused a significant increase in total phenols in the skin and in the amount of extractable anthocyanins in juice. -

The Effect of Grape Ripening Stage on Red Wine Color

THE EFFECT OF GRAPE RIPENING STAGE ON RED WINE COLOR EFFET DE LA MATURATION SUR LA COULEUR DES VINS ROUGES A.B. BAUTISTA-ORTÍN1, J.I. FERNÁNDEZ-FERNÁNDEZ2, J.M. LÓPEZ-ROCA1 and E. GÓMEZ-PLAZA*1 1 : Departamento de Tecnología de Alimentos, Nutrición y Bromatología, Facultad de Veterinaria, Universidad de Murcia. Campus de Espinardo, 30071 Murcia, Espagne 2 : I.M.I.D.A. Ctra. La Alberca s/n, 30150 Murcia, Espagne Abstract : The physico-chemical and chromatic characteristics of grapes (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Monastrell) harvested at six dif- ferent degree of ripeness (from August 16 to October 24, 2002) and that of the wines obtained from these grapes have been stu- died. The grape anthocyanins content (mg/kg of berry fresh weight) was maximum in those grapes harvested on September 11 and 16 (804.1 and 822.6 mg/kg, respectively) and decreased for grapes harvested in October. However, the results showed that the grapes with the highest anthocyanin concentration did not lead to the highest colored wines. The wines elaborated from grapes harvested on October 16 (671.9 mg of anthocyanins per kg of berry fresh weight) had the best chromatic characteristics and better withstood aging in the bottle; the extent of cell wall degradation in overly matured grapes probably facilitated the extraction of phenolic compounds from skins. However, the chromatic quality of wines made from grapes harvested one week later (October 24, the most mature grapes) was lower than that from October 16, with lower color intensity (13 % lower in the wine elaborated from grapes harvested in October 24) and a percentage of yellow color 6 % higher in this wine. -

Determination of Wine Color by UV-VIS Spectroscopy, Johan

Determination of wine colour by UV-VIS Spectroscopy following Sudraud method Johan Leinders, Product Manager Spectroscopy 1 1. A bit of background Why measure the colour of wine? •Verification of lot-to-lot consistency in wine color, particularly with varietal blends. •Monitoring color consistency over a season and from season-to-season. •Monitoring the change in wine color over time. 2 1. A bit of background 3 1. A bit of background Soil composition (available trace elements) will have an impact on the final properties. Elements like potassium in combination with grape properties will influence the final colour. 4 1. A bit of background High K concentrations are typical for red wines; equilibrium between K, tartaric acid and anthocyanin pigments complex, which is responsible for the red colour. Anthocyanin is a natural colorant which is found in leaves and grapes. About 250 different variations of the anthocyanin complex are known. They all contain the structure of the common “Flavin” molecule which will be substituted at 7 possible positions from simple -OH to complex sugar molecules. R1 R2 Fig. 2: Flavene is the base of the anthocyan 0 R3 structure, R1 to R7 represent organic groups R7 which will generate the difference among the anthocyanes R4 5 R6 R5 2. Wine Colour Determination The definition of wine colour: analysis of absorption spectra of wine samples are required. Physically, the colour is a light characteristic, measurable in terms of intensity and wavelength. Anthocyanin pigments are absorbing in the GREEN portion of the visible spectra, giving to human eye the sensation of colour RED. -

[email protected] Lusso Means “Luxury

Lusso Lusso means “luxury” in Italian. This luxurious Cabernet Sauvignon contains fruit from the St. Helena Appellation of Napa Valley and is 100% Estate Grown. Lusso comes from the best grapes we grow. Vintage: 2015 Harvest Notes: Problem free harvest that produced clean, healthy grapes resulting in high-quality wines despite the drought and a very small crop with a little uneven ripening. Picking ended in October. Blend: 100% Cabernet Sauvignon Vintage: 2014 Harvest Notes: A dream vintage, with high quality throughout. Drought conditions and small crop size did prove to be minor irritants. Everything was ready to pick in mid- August. Tasting Notes: This wine has aromas of black licorice, nutmeg, and red currant with hints of mocha and cherry concluding with a velvet-like texture and silky finish. Blend: 100% Cabernet Sauvignon Vintage: 2013 Harvest Notes: An ideal growing season with dry conditions and a long, sunny summer. Despite being a drought year it is worthy to be called superior. Tasting Notes: Aged 27 months on new French Oak this wine showcases flavors of blackberries, vanilla and espresso. This handcrafted Cabernet lingers on your palate long after the wine has left your glass. Blend: 100% Cabernet Sauvignon Vintage: 2012 Harvest Notes: An ideal season with no frosts, a mild spring and summer and a tranquil fall. We are elated by the quality and quantity of the 2012 harvest. There is a level of excellence that supersedes past vintages, going back decades. Tasting Notes: A youthful and exuberant purple hue offers classic Cabernet aromas of cassis, cocoa and brambly black cherries. -

The Influence of Cabernet Sauvignon Grape Maturity on the Concentration and Extraction of Colour and Phenolic Compounds in Wine

The influence of Cabernet Sauvignon grape maturity on the concentration and extraction of colour and phenolic compounds in wine Cynthia C. Yonker A thesis submitted for fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Adelaide School of Agriculture, Food and Wine September 2012 Table of Contents Summary .............................................................................................................................................. vi Declaration .......................................................................................................................................... viii Statement of the contributions of jointly authored papers ..................................................................... ix Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. xi Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... xiii List of Figures and Tables .................................................................................................................. xvi 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 General description of phenolic compounds in grapes and wines -

Colour Evolution of Rosé Wines After Bottling

Colour Evolution of Rosé Wines after Bottling B. Hernández, C. Sáenz*, C. Alberdi, S. Alfonso and J.M. Diñeiro Departamento de Física, Universidad Pública de Navarra, Campus Arrosadía, 31006 Pamplona, Navarra (SPAIN) Submitted for publication: July 2010 Accepted for publication: September 2010 Key words: Colour appearance, wine colour, rosé wine, colour measurement, colour evolution This research reports on the colour evolution of six rosé wines during sixteen months of storage in the bottle. Colour changes were determined in terms of CIELAB colour parameters and in terms of the common colour categories used in visual assessment. The colour measurement method reproduces the visual assessment conditions during wine tasting with respect to wine sampler, illuminating source, observing background and sample-observer geometry. CIELAB L*, a*, b*, C* and hab colour coordinates were determined at seven different times (t = 0, 20, 80, 153, 217, 300 and 473 days). The time evolution of colour coordinate values was studied using models related to linear, quadratic and exponential rise to a maximum. Adjusted R2, average standard error and CIELAB ΔE* colour difference were used to compare models and evaluate their performance. For each colour coordinate, the accuracy of model predictions was similar to the standard deviation associated with a single measurement. An average ΔE* = 0.92 with a 90 percentile value ΔE*90% = 1.50 was obtained between measured and predicted colour. These values are smaller than human colour discrimination thresholds. The classification into colour categories at different times depends on the wine sample. It was found that all wines take three to four months to change from raspberry to strawberry colour and seven to eight months to reach the redcurrant category. -

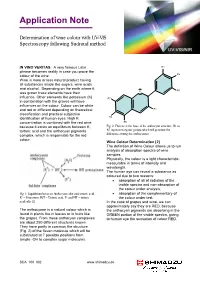

Application UV Wine Colour

Application Note Determination of wine colour with UV-VIS Spectroscopy following Sudraud method IN VINO VERITAS. A very famous Latin R1 phrase becomes reality in case you prove the colour of the wine. R2 Wine is more or less natural product having all substances inside like sugars, wine acids and alcohol. Depending on the earth where it R3 was grown trace elements have their 0 influence. Other elements like potassium (K) R7 in combination with the graves will have influences on the colour. Colour can be white and red or different depending on theoretical R4 classification and practical subjective identification of human eyes. High K R6 concentration is combined with the red wine R5 because it exists an equilibrium between K, Fig. 2: Flavene is the base of the anthocyan structure, R1 to tartaric acid and the anthocyan pigments R7 represent organic groups which will generate the complex, which is responsible for the red difference among the anthocyanes colour. Wine Colour Determination [2] The definition of Wine Colour allows us to run analysis of absorption spectra of wine samples. Physically, the colour is a light characteristic, measurable in terms of intensity and wavelength. The human eye can reveal a substance as coloured due to two reasons: • absorption of all of radiation of the visible spectra and non-absorption of the colour under analysis; Fig. 1: Equilibrium between Anthocyan color and tartaric acid, • absorption of the complementary of K+ = Potassium, H2T = Tartaric acid, T= and HT- = tartaric the colour under test. acid salts [1] In the case of grapes and wine, we can approximately say they are RED, because The anthocyane is a natural colour which is the anthocyan pigments are absorbing in the found in plants like in leaves or in fruits like GREEN portion of the visible spectra, giving the grapes. -

Kisi Wine and Food Pairing Light Yellow-Colored and Classic Style Kisi Wines Go Best with Seafood, Steamed �Sh, Meat Salads and Become Gold As They Age

KISI Kisi is one of the leading Kakhetian white vaieties after Rkatsiteli and Mtsvane Kakhuri. It has become espacially popular during the last few years. This varietal is common in the eastern part of Georgia and belongs to the family of Kakhetian grape varieties. According to scientists, Kisi occupies an medium place between Mtsvane and Rkatsiteli. Some believe it is the hybrid of these two varieties. It is relatively low-yielding harvested neither early nor late. Kisi Terroir It includes Telavi, Kvareli and Akhmeta regions. This variety is found mainly in the village of Maghraani, Akhmeta region, as well as in the villages of Argokhi and Babaneuri. Kisi has much expanded throughout Kakheti in the recent years. The Description of the Wine Traditional Kakhetian (qvevri) wines as well as KISI HARVESTING IN BABANEURI classic (European) style wines are made from Kisi. They have profound, mouth-lling presence of aromas and taste. Those that are classic in style are medium-bodied, whereas, qvevri style Kisi wines are relatively intense and full-bodied. Rarely, they are also aged in oak. Aromas Kakhetian style Kisi wines made in qvevri are perfumed with aromas of dried apricot, Imeretian saron, Georgian spices, candied nuts, orange zest, tobacco and walnuts. Classic style Kisi wines have the aromas of citrus, ripe pear, peach, sweetbrier tincture, white plum and herbs. Best Kisi Wines Classic style Mstvane Kisi wine of Telavi Marani has become the most famous brand during the last few years. Other classic style Kisi wines are produced by Viniveria, Lukasi, and Kindzmarauli Marani. The Kindzmarauli corporation also makes a semi-sweet Kisi wine. -

Winemaking Basics-Bruce Hagen.Pdf

Winemaking Basics Bruce Hagen Sourcing grapes: good wine starts with good grapes Ripeness: is generally expressed as percent sugar or °Brix (°B). The normal range is 22 – 26°B (17.5 to 19 for sparkling and 21 for some ‘crisp’ and austere whites). Use a hydrometer or a refractometer to check it. If you harvest much above 26, you should consider diluting the juice (must) with water to adjust it to downward a bit, depending on the alcohol level you are comfortable with. The problem with making wines from high °Brix grapes is that the resulting alcohol level will be high. The fermentation may stop (stick) and the wine may taste hot. Therefore, you should consider diluting the must or juice, if the sugar level is much above 26 (see adjusting the °Brix below). The alcohol conversion factor for most yeasts is about .57, but ranges from .55 to as high as .64. Multiply the °B by the conversion factor to determine the probable alcohol level: ex 26°B x .57 = 14.8%. If the °B level is 27, the resulting alcohol level will be 15.4 —very hot! If you dilute to 25, the alcohol will be 14.25%. If you dilute it to 24ºB, the alcohol will be 13.7% —quite acceptable. Whites vs. reds: § White grapes are de-stemmed, crushed, and pressed before fermentation. § Skin contact is relatively short. § Red grapes are typically de-stemmed, crushed, cold-soaked (optional), and he wine pressed off the skins and seeds after fermentation. Skin contact is lengthy, so color and tannins are more intense. -

The Effect of Terroir on Wine Business Model in Burgundy: to Make Wine Or to Sell Harvest?

Georges Giraud The Effect of Terroir on Wine Business Model in Burgundy: To Make Wine or to Sell Harvest? Georges Giraud UMR 1041 CESAER INRA AgroSup Dijon, France [email protected] Abstract The paper explores the strategies of the wine stakeholders with respect to outsourcing versus integration of the wine-making process by analyzing original and recent data issued from the companies producing wine in Burgundy. Our research question is: Does terroir matter for wine business model between staying viticulturist or becoming winemaker? We investigate this question within the mosaic of the Burgundian vineyard. A Principal Components Analysis highlights the latent variables explaining the different strategies of stakeholders in Burgundy, and a cluster analysis tries at identifying the differences existing between the winegrowers, with a special focus on the viticulturists and the winemakers. The results show that the strategies of the Burgundian wine stakeholders with respect to outsourcing vs. integration differ according to the level of Appellation d’Origine. Consequently the terroir operates as discriminant factor between outsourcing whether integrating some, if not all, of the stages of the wine-making process, including sales. Each sub-region of the Burgundian vineyard has a specific business model strongly related to the territory nesting the wine estates. 1 Introduction Even though outsourcing is considered by literature on management science as a useful trait for efficient business everywhere by reducing the agency costs, it was found that, most often, the stakeholders who process top quality products are prone to integrate the stages of working out. Other factors taken into consideration are the risks of loss of core knowledge and the increased costs.