Collaborations of Martin Scorsese with De Niro And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GANGS of NEW YORK Außer Konkurrenz GANGS of NEW YORK GANGS of NEW YORK Regie:Martin Scorsese

Wettbewerb/IFB 2003 GANGS OF NEW YORK Außer Konkurrenz GANGS OF NEW YORK GANGS OF NEW YORK Regie:Martin Scorsese USA 2002 Darsteller Amsterdam Vallon Leonardo DiCaprio Länge 168 Min. Bill Cutting Daniel Day-Lewis Format 35 mm, Jenny Everdeane Cameron Diaz Cinemascope Boss Tweed Jim Boadbent Farbe Happy Jack John C.Reilly Johnny Sirocco Henry Thomas Stabliste Pfarrer Vallon Liam Neeson Buch Jay Cocks Walter „Monk“ Steven Zaillian McGinn Brendan Gleeson Kenneth Lonergan McGloin Gary Lewis Story Jay Cocks Shang Stephen Graham Kamera Michael Ballhaus Killoran Eddie Marsan Kameraführung Andrew Rowlands Reverend Raleigh Alec McCowen Kameraassistenz Tom Lappin Mr.Schermerhorn David Hemmings Schnitt Thelma Soonmaker Jimmy Spoils Larry Gilliard,Jr. Mitarbeit James Kwei Hell-Cat Maggie Cara Seymour Pat Buba P.T.Barnum Roger Ashton- Ton Ivan Sharrock Griffiths Musik Howard Shore Einarmiger Priester Peter Hugo Daly Production Design Dante Ferreti Daniel Day-Lewis, Leonardo DiCaprio Junger Amsterdam Cian McCormack Ausstattung Stefano Ortolani Junger Johnny Andrew Gallagher Kostüm Sandy Powell O’Connell Philip Kirk Regieassistenz Joseph Reidy GANGS OF NEW YORK Bills Gang Liam Carney Casting Ellen Lewis Das südliche Manhattan in den 60er Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts, einer Zeit Gary McCormack Produktionsltg. Michael Hausman großer Unruhen in den USA – das Land steht kurz vor dem Bürgerkrieg. Für David McBlain Produzenten Alberto Grimaldi die arme Bevölkerung von New York tobt der Kampf allerdings schon lange Jennys Mädchen Katherine Wallach Harvey Weinstein – und zwar direkt vor ihrer Haustür. Korruption bestimmt die Politik, Gesetz- Carmen Hanlon Executive Producers Michael Ovitz Ilaria D’Elia Bob Weinstein losigkeit das Alltagsleben; rivalisierende Gangs kämpfen um die Vorherr- Gangmitglieder Nevan Finnegan Rick Yorn schaft auf den Straßen. -

Martin Scorsese and American Film Genre by Marc Raymond, B.A

Martin Scorsese and American Film Genre by Marc Raymond, B.A. English, Dalhousie University A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fultillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario March 20,2000 O 2000, Marc Raymond National Ubrary BibIiot~uenationak du Cana a uisitiis and Acquisitions et "IBib iogmphk Senrices services bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thése sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copy~@t in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts kom it Ni la thèse N des extraits substantiels may be printed or ohenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract This study examines the films of American director Martin Scorsese in their generic context. Although most of Scorsese's feature-length films are referred to, three are focused on individually in each of the three main chapters following the Introduction: Mean Streets (1 973), nie King of Cornedy (1983), and GoodFellas (1990). This structure allows for the discussion of three different periods in the Amencan cinema. -

The Departed Talent: Matt Damon, Leonardo Dicaprio, Jack Nicholson

The Departed Talent: Matt Damon, Leonardo DiCaprio, Jack Nicholson, Mark Wahlberg, Alec Baldwin, Vera Farmiga, Martin Sheen, Ray Winstone. Date of review: Thursday the 12th of October, 2006. Director: Martin Scorsese Classification: MA (15+) Duration: 152 minutes We rate it: Five stars. For any serious cinemagoer or lover of film as an art form, the arrival of a new film by Martin Scorsese is a reason to get very excited indeed. Scorsese has long been regarded as one of the greatest of America’s filmmakers; since the mid-1980s he has been regarded as one of the greatest filmmakers in the world, period. With landmark works like Taxi Driver (1976), Raging Bull (1980), Goodfellas (1990) and Bringing Out the Dead (1999) to his credit, Scorsese is a director for whom any actor will go the distance, and the casts the director manages to assemble for his every project are extraordinarily impressive. As a visualist Scorsese is a force to be reckoned with, and his soundtracks regularly become known as classic creations; his regular collaborators, including editor Thelma Schoonmaker and cinematographer Michael Ballhaus are the best in their respective fields. Paraphrasing all of this, one could justifiably describe Martin Scorsese as one of the most important and interesting directors on the face of the planet. The Departed, Scorsese’s newest film, is on one level a remake of a very successful Hong Kong action thriller from 2002 called Infernal Affairs. That film, written by Felix Chong and directed by Andrew Lau, set the box office on fire in Hong Kong and became a cult hit around the world. -

Once Upon a Time … in Santa Clarita: Tarantino Movie Opens Thursday

By: Caleb Lunetta, July 25, 2019 Once Upon a Time … In Santa Clarita: Tarantino movie opens Thursday Hollywood director Quentin Tarantino is known for his genre-defying blockbuster films that combine elements of art house, violence and comedy in his Academy Award-winning films. And the San Fernando Valley resident calls Santa Clarita “a special place,” according to local film property owners who have played host to the luminary for his latest film that debuts tonight, “Once Upon a Time … In Hollywood.” The latest installment in the Tarantino filmography follows the story of “a faded television actor and his stunt double (who) strive to achieve fame and success in the film industry during the final years of Hollywood’s Golden Age in 1969 Los Angeles,” according to IMDb.com. The film features Leonardo DiCaprio, Brad Pitt and Margot Robbie. Tarantino and movie fans were given a teaser trailer where the opening shot was that of Melody Ranch’s “Main Street” set. Veluzat said that the production team had been working with the studio for a couple months, from planning to setting up to filming, and for him, it was a special experience. Tarantino has filmed two of his last three movies at Melody Ranch in Newhall, according to studio manager Daniel Veluzat, and he’s praised the SCV in interviews and conversations with local residents. He really does like it here, said Veluzat, in reference to a question about why Tarantino has filmed his movies at Melody Ranch. “He calls it a special place,” he said. And on Thursday night, “Once Upon a Time” opens in theaters across the country, including the Santa Clarita Valley, featuring scenes shot at both Melody Ranch and the Saugus Speedway. -

Toxic Masculinity and the Revolutionary Anti-Hero

FIGHTING HACKING AND STALKING: TOXIC MASCULINITY AND THE REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-HERO A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A In partial fulfillment of 3^ the requirements for the Degree kJQ Masters of Arts *0 4S In Women and Gender Studies by Robyn Michelle Ollodort San Francisco, California May 2017 Copyright by Robyn Michelle Ollodort 2017 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Fighting, Hacking, and Stalking: Toxic Masculinity and the Revolutionary Anti-Hero by Robyn Michelle Ollodort, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in Women and Gender Studies at San Francisco State University. Martha Kenney; Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Women and Gender Studies Professor, History FIGHTING, HACKING, AND STALKING: TOXIC MASCULINITY AND THE REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-HERO Robyn Michelle Ollodort San Francisco, California 2017 Through my analyses of the films Taxi Driver (1976) and Fight Club (1999), and the television series Mr. Robot (2105), I will unpack the ways each text represents masculinity and mental illness through the trope of revolutionary psychosis, the ways these representations reflect contemporaneous political and social anxieties, and how critical analyses of each text can account for the ways that this trope fails to accurately represent the lived experiences of men and those with mental illnesses. In recognizing the harmful nature of each of these representations’ depictions of both masculinity and mental illness, we can understand why such bad tropes circulate, and how to recognize and refuse them, or make them better. -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

Ominous Faultlines in a World Gone Wrong: Courmayeur Noir in Festival Randy Malamud

Ominous Faultlines in a World Gone Wrong: Courmayeur Noir In Festival Randy Malamud In the sublime shadows of the Italian Alps, Courmayeur Confidential, Mulholland Drive, The Dark Knight trilogy), Noir In Festival’s 23-year run suggests America’s monop- hyper-noir (even ‘noirer’ than noir! Sin City, Django Un- 1 oly on this dark cinematic tradition may be on the wane. chained), and tech noir (The Matrix, cyberpunk) it remained The roots of film noir wind broadly through the geogra- a made-in-America commodity. phy of film history. One assumes it’s American to the core: Courmayeur’s 2013 program proved that contemporary Humphrey Bogart, Orson Welles, Dashiell Hammett. But noir, like anything poised to thrive nowadays, is indubita- au contraire, the term itself (obviously) emanates from bly global. Its December event featured Hong Kong film- a Gallic sensibility: French critic Nino Frank planted the maker Johnny To’s wonderfully macabre comedy, Blind flag when he coined ‘‘film noir’’ in 1946. He was discussing Detective (with the funniest crime reenactment scenes American films, but still: it took a Frenchman to appreci- ever); Erik Matti’s Filipino killer-thriller On the Job; and 2 ate them. Or maybe the genre is German, growing out Argentinian Lucı´a Puenzo’s resonantly disturbing Wakol- of Weimar expressionism, strassenfilm (street stories), da, an adaptation of her own novel about Josef Mengele’s 3 Lang’s M. 1960 refuge in a remote Patagonian Naziphile community. In fact, film noir is a hybrid which began to flourish in The Black Lion jury award went to Denis Villeneuve’s 1940s Hollywood, but was molded by displaced Europeans Enemy, a Canadian production adapted from Jose´ Sarama- (Billy Wilder, Alfred Hitchcock, Otto Preminger) and go’s Portuguese novel The Double (and with a bona fide keenly inflected by their continental aesthetic and philo- binational spirit). -

The Color of Money”

David Alciatore, PhD (“Dr. Dave”) ILLUSTRATED PRINCIPLES “Billiards on the Big Screen – The Color of Money” Note: Supporting narrated video (NV) demonstrations, high-speed video (HSV) clips, and technical proofs (TP) can be accessed and viewed online at billiards.colostate.edu. The reference numbers used in the article (e.g., NV A.7) help you locate the resources on the website. If you don’t have access to the Internet, or if you have a slow connection (e.g., a modem), you may want to view the resources from a CD-ROM instead. To order one, send a check or money order (payable to David Alciatore) for $21.45 (includes S&H) to: Pool Book CD; 626 S. Meldrum St.; Fort Collins, CO 80521. The CD-ROM is compatible with both PCs and MACs. This is the second article in my “Billiards on the Big Screen” series, where I illustrate and describe interesting shots from movies with major billiards themes. Last month, I presented some shots from the classic billiards flick: “The Hustler.” By the way, if you want to refer back to any of my previous articles and online resources, you can access them online at billiards.colostate.edu. This month’s article deals with the huge box-office success: “The Color of Money.” In my next two articles, I will show shots from “Pool Hall Junkies” and “Donald in Mathmagic Land.” ”The Color of Money” (1986, Touchstone Pictures) is the story of two hustlers who teach each other a few things about pool and life. Fast Eddie Felson (played by Paul Newman), a seasoned hustler, discovers Vincent (played by Tom Cruise), an immature and young hustler with great talent and potential. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

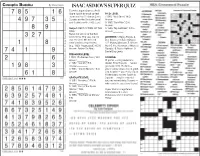

Isaac Asimov's Super Quiz

PAGE 6A WEDNESDAY, JULY 7, 2021 TIMES WEST VIRGINIAN ADVICE Dear Mayo Clinic Q and A: Simplify health Annie Annie Lane goals for success Syndicated Columnist that includes things such as: every other day with a meal. This can be By Cynthia Weiss – Ridding homes of any desserts, candy, something you can easily manage and Mayo Clinic News Network soda and processed food. feel successful with. Just remember not Dear Mayo Clinic: I am a mom of three – Promising to buy and eat only whole to overload it with dressing. Or instead of kids under 10, and I have struggled with foods made from scratch. grabbing a handful of chips for a snack, Twin brothers weight loss for years. I am challenged – Going to the gym five or more days a grab an apple or a cheese stick. Consider the between family and work obligations to week and working out for an hour each time. same substitutions for your children so you maintain a healthy lifestyle. I always start – Hiring a life coach to help get their life won’t be tempted. can’t get along off strong, but then I get overwhelmed and together. Over time, one change will lead to stop. Last month, despite trying to eat right – Reducing work stress. another. As you implement healthy things Dear Annie: I come from a big family. I and working out daily, I gained weight after Does this sound familiar? into your routine, you will build more have seven brothers and two sisters, and I’m two weeks instead of losing it. -

Scorses by Ebert

Scorsese by Ebert other books by An Illini Century roger ebert A Kiss Is Still a Kiss Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook Behind the Phantom’s Mask Roger Ebert’s Little Movie Glossary Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion annually 1986–1993 Roger Ebert’s Video Companion annually 1994–1998 Roger Ebert’s Movie Yearbook annually 1999– Questions for the Movie Answer Man Roger Ebert’s Book of Film: An Anthology Ebert’s Bigger Little Movie Glossary I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie The Great Movies The Great Movies II Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert Your Movie Sucks Roger Ebert’s Four-Star Reviews 1967–2007 With Daniel Curley The Perfect London Walk With Gene Siskel The Future of the Movies: Interviews with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas DVD Commentary Tracks Beyond the Valley of the Dolls Casablanca Citizen Kane Crumb Dark City Floating Weeds Roger Ebert Scorsese by Ebert foreword by Martin Scorsese the university of chicago press Chicago and London Roger Ebert is the Pulitzer The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 Prize–winning film critic of the Chicago The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London Sun-Times. Starting in 1975, he cohosted © 2008 by The Ebert Company, Ltd. a long-running weekly movie-review Foreword © 2008 by The University of Chicago Press program on television, first with Gene All rights reserved. Published 2008 Siskel and then with Richard Roeper. He Printed in the United States of America is the author of numerous books on film, including The Great Movies, The Great 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 Movies II, and Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert, the last published by the ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18202-5 (cloth) University of Chicago Press. -

Understanding Steven Spielberg

Understanding Steven Spielberg Understanding Steven Spielberg By Beatriz Peña-Acuña Understanding Steven Spielberg Series: New Horizon By Beatriz Peña-Acuña This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Beatriz Peña-Acuña Cover image: Nerea Hernandez Martinez All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0818-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0818-7 This text is dedicated to Steven Spielberg, who has given me so much enjoyment and made me experience so many emotions, and because he makes me believe in human beings. I also dedicate this book to my ancestors from my mother’s side, who for centuries were able to move from Spain to Mexico and loved both countries in their hearts. This lesson remains for future generations. My father, of Spanish Sephardic origin, helped me so much, encouraging me in every intellectual pursuit. I hope that contemporary researchers share their knowledge and open their minds and hearts, valuing what other researchers do whatever their language or nation, as some academics have done for me. Love and wisdom have no language, nationality, or gender. CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 3 Spielberg’s Personal Context and Executive Production Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 19 Spielberg’s Behaviour in the Process of Film Production 2.1.