Staging Matters: Mirrors and Memories Mark Gisbourne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bregenz's Floating Stage

| worldwide | austria PC Control 04 | 2016 Art, technology and nature come together to deliver a great stage experience Advanced stage control technology produces magical moments on Bregenz’s floating stage The seventy-year history of the Bregenz Festival in Austria has been accompanied by a series of technical masterpieces that make watching opera on Lake Constance a world-famous experience. From July to August, the floating stage on Lake Constance hosts spectacular opera performances that attract 7,000 spectators each night with their combination of music, singing, state-of-the- art stage technology and effective lighting against a spectacular natural backdrop. For Giacomo Puccini’s “Turandot”, which takes place in China, stage designer Marco Arturo Marelli built a “Chinese Wall” on the lake utilizing complex stage machinery controlled by Beckhoff technology. | PC Control 04 | 2016 worldwide | austria © Bregenzer Festspiele/Karl Forster © Bregenzer Festspiele/Karl The centerpiece of the floating stage is the round area at its center with an extendable rotating stage and two additional performance areas below it. The hinged floor features a video wall on its under- side for special visual effects, projecting various stage setting images. The tradition of the Bregenz Festival goes back to 1946, when the event started The backdrop that Marco Arturo Marelli designed for “Turandot” consists with a performance of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s musical comedy “Bastian of a 72-meter-long wall that snakes across the stage like a giant dragon. A and Bastienne” on two gravel barges anchored in the harbor. The space on the sophisticated structure of steel, concrete and wood holds the 29,000 pieces barges soon became too small, and the organizers decided to build a real stage in place. -

Saison 2017/18 Établissement Public Salle De Concerts Grande-Duchesse Joséphine-Charlotte

Saison 2017/18 Établissement public Salle de Concerts Grande-Duchesse Joséphine-Charlotte Philharmonie Luxembourg Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg Saison 2017/18 Nous remercions nos partenaires qui, Partenaires d’événements: en associant leur image à la Philharmonie et à l’Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg et en soutenant leur programmation, permettent leur diversité et l’accès à un public plus large. Partenaire officiel: Partenaire automobile exclusif: Partenaires média: Sommaire / Inhalt / Content Une extraordinaire diversité 4 Découvrir la musique Musek erzielt (4–8 ans) 216 Bienvenue! 6 L’imagination au pouvoir Philou F (5–9 ans) 218 POST Luxembourg – Partenaire officiel 11 Artiste en résidence: Jean-François Zygel 118 Philou D (5–9 ans) 222 Dating 122 Familles (6–106 ans) 226 Les dimanches de Jean-François Zygel 124 Miouzik F (9–12 ans) 230 Orchestre Lunch concerts 126 Miouzik D (9–12 ans) 232 La beauté d’un cheminement artistique Yoga & Music 128 iPhil (14–18 ans) 236 Directeur musical: Gustavo Gimeno 16 résonances 130 Workshops 240 Grands rendez-vous 20 PhilaPhil 132 Aventure+ 24 Fondation EME 135 Fräiraim & Partenaires L’heure de pointe 30 Fräiraim 246 Fest- & Bienfaisance-Concerten 32 Jazz, World & Chill Solistes Européens, Luxembourg – Retour aux sources Une métaphore musicale de la démocratie Cycle Rencontres SEL A 250 Artiste en résidence: Paavo Järvi 36 Orchestre en résidence: Solistes Européens, Luxembourg – Grands orchestres 40 JALCO & Wynton Marsalis 140 Cycle Rencontres SEL B 252 Grands chefs 44 Jazz & beyond -

Architecture and Space Our Congress Centre in Pictures and Figures Culture Meets Congress and Finds Him Devastatingly Good Looking

Architecture and Space Our congress centre in pictures and figures Culture meets Congress and finds him devastatingly good looking Mrs Culture and Mr Congress appear from opposite sides of the plaza in front of Bregenz Festival House. She is very elegantly dressed, he has more of a sporty look. Both of them are presumably on their way to an event taking place in the centre. As they approach one another it is clear how glad they are to meet again. Culture: Hello! Well now, you look damn good. Congress: You’re not the first person to say so. Culture (a little taken aback): And you’re pretty self-confident with it. Congress: Did I just adopt the wrong tone? Culture : The right tone is more my domain. Congress: In the figurative sense, yes. But technically speaking it’s mine. Sound, lighting, stage set are my responsibilities, and I feel equal to them all. Culture : There seem to be developments in your life which I have never gone through. Congress: That’s right. I’m doing a lot of sport at the moment. Culture: Please don’t do too much. I’m not too keen on muscle-bound types. Congress: Don’t worry, I’m mainly building up my stamina. The body is my house, it’s got to be solid. Culture : The body is the house in which your soul and mind dwell. Congress: Yeah, them too. But without a strong body... Culture : The body matters a lot to me, too, but not in the sense of what’s external. -

Polish Composer's Masterpiece Premiered After 31 Years

Polish Composer’s Masterpiece Premiered after 31 Years Anna S. Debowska - July 23, 2013 ''The Merchant of Venice'' at the festival in Bregenz (Photo Bregenzer Festspiele / Karl Forster) The real bombshell of the Bregenzer Festspiele in Austria was “The Merchant of Venice.” This was the first time the opera by Andrzej Czajkowski – an eccentric piano genius and survivor of the Warsaw ghetto – has been staged. The outstanding work will have its Polish premiere next year. The classical music festival in Bregenz on Lake Constance is organized with two aims. The festival presents spectacular productions of famous operas on its stage on the water. These are attended by tens of thousands of listeners from Austria, Germany, Switzerland, and England. It also, ambitiously, highlights works by forgotten composers. This two-pronged approach is the brainchild of the English director David Pountney, who has been the artistic director of the Bregenzer Festspiele for nine years. He decided to revive the tradition of the festival, the first edition of which took place in 1946, on the stage built on the lake. He already has staged “Il Travatore,” “Aida,” “Andrea Chenier,” and this year, “The Magic Flute.” He provides light, witty, and cleverly high-tech productions that are open to innovative and quirky ideas. The performances on the water always start in the evening as darkness slowly settles on the lake. Festival organizers use a sound system, but the productions are performed by very talented singers who are able to project in the unusual setting. Every evening, close to seven thousand spectators gather at the floating amphitheater under the night sky. -

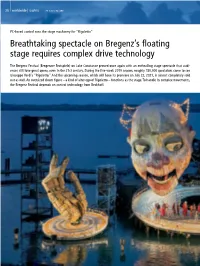

Breathtaking Spectacle on Bregenz's Floating Stage Requires Complex

| 26 worldwide | austria PC Control 02 | 2021 PC-based control runs the stage machinery for “Rigoletto” Breathtaking spectacle on Bregenz’s floating stage requires complex drive technology The Bregenz Festival (Bregenzer Festspiele) on Lake Constance proved once again with an enthralling stage spectacle that audi- ences still love great opera, even in the 21st century. During the five-week 2019 season, roughly 180,000 spectators came to see Giuseppe Verdi’s “Rigoletto.” And the upcoming season, which will have its premiere on July 22, 2021, is almost completely sold out as well. An oversized clown figure – a kind of alter ego of Rigoletto – functions as the stage. To handle its complex movements, the Bregenz Festival depends on control technology from Beckhoff. | PC Control 02 | 2021 worldwide | austria 27 The main With a diameter of 22 meters (72 feet) and a total area cabinet and of 338 square meters (3,638 square feet), the collar the panel for forms the central stage area. Mounted on a seesaw, controlling the the head can be moved across the entire stage. hydraulics are each equipped with a built-in 15-inch CP6602 Panel PC from Beckhoff. © Bregenzer Festspiele/Anja Köhler/andereart.de © Bregenzer Festspiele/Anja | 28 worldwide | austria PC Control 02 | 2021 The “Seebühne Bregenz” (Bregenz floating stage) is famous for its spectacu- and to subject each of them to a safety analysis with regard to their drive lar productions, but Philipp Stölzl’s staging exceeds all past performances in force, load and speed,” explains Wolfgang Urstadt, the technical director of terms of aesthetics as well as technical feasibility. -

In Association With

OVERTURE OPERA GUIDES in association with It is a pleasure to be able to welcome this Overture Opera Guide to The publisher John Calder began the Opera Guides series un- Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), the eighteenth to be der the editorship of the late Nicholas John in association with published since the series in association with ENO was relaunched English National Opera in 1980. It ran until 1994 and even- in 2010. tually included forty-eight titles, covering fifty-eight operas. The books in the series were intended to be companions to the Mozart’s penultimate opera – written in the vernacular, with spoken works that make up the core of the operatic repertory. They dialogue and music that ranges from the deeply serious to the light- contained articles, illustrations, musical examples and a com- hearted – has delighted audiences since its premiere in September 1791 plete libretto and singing translation of each opera in the series, at a small theatre tucked away in the Viennese suburbs. Exploring as well as bibliographies and discographies. key issues of the Enlightenment, Die Zauberflöte is one of Mozart’s major contributions to the lyric theatre, and no opera company The aim of the present relaunched series is to make available can be without a production of it for long. This guide’s publication again the guides already published in a redesigned format with coincides with a revival at ENO of director Simon McBurney’s new illustrations, many revised and newly commissioned arti- staging of the work, a production whose innovative theatricality has cles, updated reference sections and a literal translation of the won many new admirers for the opera. -

Download Bio

Mauricio Trejo www.MauricioTrejo.com [email protected] Mexican-Italian Tenor, Mauricio Trejo, was recently distinguished by the Wagner Society of New York as a promising Wagnerian Tenor. In August 2016 Mr.Trejo received a full scholarship to further and expand hi Wagnerian Tenor repertoire at the Lotte Lehmann Akademie where he also perform concerts in Germany. He has been hailed as "a tenor with a silver bullet top," "the possessor of a clear and powerful instrument of great beauty,” "a revelation." (Luzerner Zeitung) A Sony Classical Recording Artist as one of the original American Tenors. Mauricio has been honored with numerous awards such as the Placido Domingo Scholarship under the auspices of SIVAM, the Panasonic Scholar of the Year, a winner in the International Caruso Competition and a finalist in the Arena di Verona Turandot Competition in the role of Calaf. Mr. Trejo has also been featured in television performances in a nationwide airing on PBS and on TV Azteca in Mexico In May 2017 Mauricio made his debut in the role of Otello by Giuseppe Verdi in New York City. He is also currently expanding his repertory in preparation of Siegfried, Siegmund, Bacchus, and Florestan. Before expanding to the dramatic and Wagnerian repertoire, he performed the leading tenor roles in Tosca, Cavalleria Rusticana, Il Tabarro, Turandot, I Pagliacci, Madama Butterfly, La Boheme, La Traviata, Rigoletto, Lucia di Lammermoor, L'Elisir D'Amore and Der Rosenkavalier. Mauricio's international operatic and concert career has taken him to North, Central and South America, Europe and the Middle East. Performed with companies that include the Opera Orchestra Of New York, Bregenzer Festspiele in Austria, Opernhaus Zurich, Santa Fe Opera, Sarasota Opera, Opera Santa Barbara, Lyric Opera of Vinrginia, New Israeli Opera, The New York Grand Opera, and the Opera Nacional de Panama. -

Frankenstein

FRANKENSTEIN Mark Grey PRODUCTIE / PRODUCTION De Munt / La Monnaie 8, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19 & 20 MAART / MARS 2019 DE MUNT / LA MONNAIE Deze productie werd gerealiseerd met de steun van de Tax Shelter van de Belgische Federale Overheid, in samenwerking met Prospero NV en Taxshelter.be powered by ING. / Cette production a été réalisée avec le soutien du Tax Shelter du Gouvernement fédéral belge, en collaboration avec Prospero SA et Taxshelter.be powered by ING. FRANKENSTEIN Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus Opera in two acts based on the novel by Mary Shelley Libretto by Júlia Canosa i Serra Music by Mark Grey Opdrachtwerk van de Munt / Commande de la Monnaie Wereldcreatie / Création mondiale BASSEM AKIKI Muzikale leiding / Direction musicale Oorspronkelijk idee en regie / ÀLEX OLLÉ (LA FURA DELS BAUS) Idée originale et mise en scène ALFONS FLORES Decors / Décors LLUC CASTELLS Kostuums / Costumes URS SCHÖNEBAUM Belichting / Éclairages FRANC ALEU Video / Vidéo Regiemedewerkster / SUSANA GOMEZ Collaboratrice à la mise en scène ÀLEX OLLÉ, Dramaturgie JÚLIA CANOSA I SERRA & MARK GREY MARTINO FAGGIANI Koorleider / Chef des chœurs SCOTT HENDRICKS Victor Frankenstein TOPI LEHTIPUU Creature ELEONORE MARGUERRE Elizabeth ANDREW SCHROEDER Walton CHRISTOPHER GILLETT Henry STEPHAN LOGES Blind Man / Father HENDRICKJE VAN KERCKHOVE Justine WILLIAM DAZELEY Prosecutor SYMFONIEORKEST EN KOOR VAN DE MUNT / ORCHESTRE SYMPHONIQUE ET CHŒURS DE LA MONNAIE Konzertmeister NANA KAWAMURA Muziekuitgave / Éditions musicales Virrat Music Duur van de voorstelling: -

Agnes Martin Selected Bibliography Books

AGNES MARTIN SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS AND EXHIBITION CATALOGUES 2019 Hannelore B. and Rudolph R. Schulhof Collection (exhibition catalogue). Text by Gražina Subelytė. Venice, Italy: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, 2019. 2018 Agnes Martin / Navajo Blankets (exhibition catalogue). Interview with Ann Lane Hedlund and Nancy Princenthal. New York: Pace Gallery, 2018. American Masters 1940–1980 (exhibition catalogue). Texts by Lucina Ward, James Lawrence and Anthony E Grudin. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2018: 162–163, illustrated. An Eccentric View (exhibition catalogue). New York: Mignoni Gallery, 2018: illustrated. “Agnes Martin: Aus ihren Aufzeichnungen über Kunst.” In Küstlerinnen schreiben: Ausgewählte Beiträge zur Kunsttheorie aus drei Jahrhunderten. Edited by Renate Kroll and Susanne Gramatzki. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag GmbH, 2018: 183–187, illustrated. Ashton, Dore. “Dore Ashton on Agnes Martin.” In Fifty Years of Great Art Writing. London: Hayward Gallery Publishing, 2018: 53–61, illustrated. Agnes Martin: Selected Bibliography-Books and Exhibition Catalogs 2 Fritsch, Lena. “’Wenn ich an Kunst denke, denke ich an Schönheit’ – Agnes Martins Schriften.” In Küstlerinnen schreiben: Ausgewählte Beiträge zur Kunsttheorie aus drei Jahrhunderten. Edited by Renate Kroll and Susanne Gramatzki. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag GmbH, 2018: 188–197. Guerin, Frances. The Truth is Always Grey: A History of Modernist Painting. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2018: plate 8, 9, illustrated. Intimate Infinite: Imagine a Journey (exhibition catalogue). New York: Lévy Gorvy, 2018: 100–101, illustrated. Martin, Henry. Agnes Martin: Pioneer, Painter, Icon. Tucson, Arizona: Schaffner Press, 2018. Martin, Agnes. “Agnes Martin: Old School.” In Auping, Michael. 40 Years: Just Talking About Art. Fort Worth, Texas and Munich: Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth; DelMonico Books·Prestel, 2018: 44–45, illustrated. -

George Condo's

A New Show That Puts George Condo Next to Picasso By: Hilary Moss November 18, 2016 From left: George Condo’s “Telepoche Cut-Out,” 1989; Henri Matisse’s “Vegetable Elements,” 1947. When Udo Kittelmann, the director of Berlin’s Nationalgalerie, initially floated the idea of an exhibition that would position George Condo’s work against pieces from Museum Berggruen’s 20th-century art collection, the American painter had some doubts. “Udo said, ‘You make so many modernist references,’ but I didn’t want to have a George Condo at random sitting next to a Picasso or a Matisse,” Condo remembers. “You’d see the absolute differences, as much as it appears to be referential.” Kittelmann spent two full days rummaging through the artist’s New York storage space, finally landing on a nontraditional approach, and convinced Condo to go along with it: The curator cleared out the museum’s 28 rooms, installed his pick of 118 Condo paintings, drawings, collages and sculptures — most never shown before — and then reinstalled parts of the Berggruen’s collection accordingly. The resulting show, called “Confrontation,” opens tomorrow in Berlin and places, for instance, Paul Klee tableaus marked by the expressionist’s swooping signature near a mid- ’80s, semi-surrealist Condo painting of his last name. Blue- and rose-period Picassos are complemented by similarly hued Condos; Georges Braque’s Cubist compositions echo a more recent oil painting of a man’s head split by a meat cleaver; and Matisse’s cutouts stand next to a few of Condo’s late-’80s and early-’90s collages. -

Quaybrothers PREVIEW.Pdf

contents 6 Foreword Glenn D. Lowry 8 Acknowledgments 10 THE MANIC DEPARTMENT STORE New Perspectives on the Quay Brothers Ron Magliozzi 16 THOSE WHO DESIRE WITHOUT END Animation as “Bachelor Machine” Edwin Carels 21 O N DECIPHERING THE PHARMACIST’S PRESCRIPTION FOR LIP-READING PUPPETS A project by the Quay Brothers 28 PlATES 62 Works by the Quay Brothers 63 Selected Bibliography 64 Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art The book also contains a project by the Quay Brothers on the front and back inside covers. Ron Magliozzi t is gratifying to report, right at the start, that the As illustrators, stage designers, and film- The twins’ “facility for drawing”6 was encouraged by reputed inaccessibility of the Quay Brothers’ work is a makers in a range of genres, the Quays have their family. At home, snowy pastoral landscapes of a Imyth. The challenge of deciphering meaning and narra- penetrated many fields of visual expression red barn at different distances were hung side by side, tive in the roughly thirty theatrical shorts and two features for a number of different audiences, from coincidentally suggesting a cinema tracking shot. Stark that the filmmakers have produced since 1979 is real avant-garde cinema and opera to publication countryside landscapes dotted with trees appeared indeed, a characteristic of their work that they adopted art and television advertising. Looking at commonly in their youthful drawings, often with ele- on principle when they were still students. Interpreters of their artistic endeavors as a whole, in the ments of telling human interest, as in Bicycle Course for their stop-motion puppet films, such as the defining Street context of fresh biographical information and Aspiring Amputees (1969) and Fantasy-Penalty for of Crocodiles (1986), have described them as alchemists, new evidence of their creativity, provides Missed Goal (c.1968). -

Kerry James Marshall Born 1955 in Birmingham, Alabama

This document was updated November 27, 2020. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Kerry James Marshall Born 1955 in Birmingham, Alabama. Lives and works in Chicago. EDUCATION 1999 Honorary Doctorate, Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles 1978 B.F.A., Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Kerry James Marshall: Collected Works, Rennie Museum, Vancouver Kerry James Marshall: History of Painting, David Zwirner, London [catalogue] Kerry James Marshall: Works on Paper, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio 2016 Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago [itinerary: The Met Breuer, New York; The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles] [catalogue] 2014 Kerry James Marshall: Look See, David Zwirner, London [catalogue published in 2015] 2013 Kerry James Marshall: DOLLAR FOR DOLLAR, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York Kerry James Marshall: Garden of Delights, Contemporary Art Museum, St. Louis, Missouri [part of Front Room series] Kerry James Marshall: In the Tower, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC [exhibition brochure] Kerry James Marshall: Painting and Other Stuff, Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen, Antwerp [itinerary: Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen; Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid] [catalogue] 2012 Kerry James Marshall. Black Night Falling: Black holes and constellations, moniquemeloche, Chicago Recent Acquisitions, Part III: Kerry James Marshall, Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard