Ruining the King's Cause in America: the Defeat of the Loyalists in the R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The History of the American Revolution, Vol. 1 [1789]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6558/the-history-of-the-american-revolution-vol-1-1789-46558.webp)

The History of the American Revolution, Vol. 1 [1789]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, vol. 1 [1789] The Online Library Of Liberty Collection This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, foundation established to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, or to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 900 books and other material and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and Web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. LIBERTY FUND, INC. 8335 Allison Pointe Trail, Suite 300 Indianapolis, Indiana 46250-1684 Online Library of Liberty: The History of the American Revolution, vol. 1 Edition Used: The History of the American Revolution, Foreword by Lester H. -

The Fourteenth Colony: Florida and the American Revolution in the South

THE FOURTEENTH COLONY: FLORIDA AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION IN THE SOUTH By ROGER C. SMITH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Roger C. Smith 2 To my mother, who generated my fascination for all things historical 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Jon Sensbach and Jessica Harland-Jacobs for their patience and edification throughout the entire writing process. I would also like to thank Ida Altman, Jack Davis, and Richmond Brown for holding my feet to the path and making me a better historian. I owe a special debt to Jim Cusack, John Nemmers, and the rest of the staff at the P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History and Special Collections at the University of Florida for introducing me to this topic and allowing me the freedom to haunt their facilities and guide me through so many stages of my research. I would be sorely remiss if I did not thank Steve Noll for his efforts in promoting the University of Florida’s history honors program, Phi Alpha Theta; without which I may never have met Jim Cusick. Most recently I have been humbled by the outpouring of appreciation and friendship from the wonderful people of St. Augustine, Florida, particularly the National Association of Colonial Dames, the ladies of the Women’s Exchange, and my colleagues at the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum and the First America Foundation, who have all become cherished advocates of this project. -

S39169 Samuel Baker

Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters Pension application of Samuel Baker S39169 f26NC Transcribed by Will Graves 1/6/08 rev'd 8/8/14 [Methodology: Spelling, punctuation and/or grammar have been corrected in some instances for ease of reading and to facilitate searches of the database. Where the meaning is not compromised by adhering to the spelling, punctuation or grammar, no change has been made. Corrections or additional notes have been inserted within brackets or footnotes. Blanks appearing in the transcripts reflect blanks in the original. A bracketed question mark indicates that the word or words preceding it represent(s) a guess by me. The word 'illegible' or 'indecipherable' appearing in brackets indicates that at the time I made the transcription, I was unable to decipher the word or phrase in question. Only materials pertinent to the military service of the veteran and to contemporary events have been transcribed. Affidavits that provide additional information on these events are included and genealogical information is abstracted, while standard, 'boilerplate' affidavits and attestations related solely to the application, and later nineteenth and twentieth century research requests for information have been omitted. I use speech recognition software to make all my transcriptions. Such software misinterprets my southern accent with unfortunate regularity and my poor proofreading skills fail to catch all misinterpretations. Also, dates or numbers which the software treats as numerals rather than -

Reading Comprehension: Declaration of Independence

Reading Comprehension: Declaration of Independence The main purpose of America's Declaration of Independence was to explain to foreign nations why the colonies had chosen to separate themselves from Great Britain. The Revolutionary War had already begun, and several major battles had already taken place. The American colonies had already cut most major ties to England and had established their own congress, currency, army, and post office. On June 7, 1776, at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Richard Henry Lee voiced a resolution that the United States should be completely free of England's influence, and that all political ties between the two countries should be dissolved. Congress agreed and began plans to publish a formal declaration of independence and appointed a committee of five members to draft the declaration. Thomas Jefferson was chosen to draft the letter, which he did in a single day. Four other members—Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams—were part of the committee to help Jefferson. In the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson explained that a body of people has a right to change governments if that government becomes oppressive (unfair and controlling). He further explained that governments fail when they no longer have the consent of the governed. Since Parliament clearly lacked the consent of the American colonists to govern them, it was no longer legitimate. The Declaration was presented to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on July 2, 1776. It was approved with a few minor changes. Of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence, John Hancock, of Massachusetts, was the first. -

BATTLEGROUND of FREEDOM No State Made a Greater Contribution to the Winning of America

A~ '562. 2 .· ~\l-2. C'op~ \ BATTLEGROUND OF FREEDOM No state made a greater contribution to the winning of America. Both Kosciusko and Count Pulaski, the Polish independence and the founding of the nation than South patriots, served with distinction in South Carolina. ·Carolina. Her sons served ably and well in the Con For nearly four years, South Carolina was spared the tinental Congress and many of her sons laid down their horrors of war, then Charleston fell in May, 1780, and lives on the altar of freedom so that liberty and in South Carolina became a conquered province. Except for dependence could be achieved. Her heroine daughters Marion, Sumter and Pickens and their gallant followers, are legends of the land. it seemed all was lost. After Camden, the tide began to Upon the soil of South Carolina more battles were turn with Musgrove's Mill, Hanging Rock, King's Moun fought than in any other state. Both Virginia and tain and Blackstock's. In October, Nathanael Greene, the Massachusetts have been referred to as "The Cradle of fighting Quaker from Rhode Island, was given command Liberty." South Carolina was "The Battleground of of the Continental troops in the South. Daniel Morgan, an Freedom." Men from many states and nations came to epic soldier of great courage, returned to active duty, In South Carolina and fought and died. Where they fought, 17'81, the British suffered a major defeat at Cowpens. The bled and died is sacred ground, consecrated by the blood Battles of Ninety Six, Hobkirk's Hill, and most promi of patriots. -

Coercion, Cooperation, and Conflict Along the Charleston Waterfront, 1739-1785: Navigating the Social Waters of an Atlantic Port City

Coercion, Cooperation, and Conflict along the Charleston Waterfront, 1739-1785: Navigating the Social Waters of an Atlantic Port City by Craig Thomas Marin BA, Carleton College, 1993 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 1998 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Craig Thomas Marin It was defended on December 4, 2007 and approved by Dr. Seymour Drescher, University Professor, Department of History Dr. Van Beck Hall, Associate Professor, Department of History Dr. John Markoff, Professor, Department of Sociology Dissertation Director: Dr. Marcus Rediker, Professor, Department of History ii Copyright © by Craig Thomas Marin 2007 iii Coercion, Cooperation, and Conflict along the Charleston Waterfront, 1739-1785: Navigating the Social Waters of an Atlantic Port City Craig Thomas Marin, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 This dissertation argues that the economic demands of the eighteenth-century Atlantic world made Charleston, South Carolina, a center of significant sailor, slave, and servant resistance, allowing the working people of the city’s waterfront to permanently alter both the plantation slave system and the export economy of South Carolina. It explores the meanings and effects of resistance within the context of the waterfront, the South Carolina plantation economy, and the wider Atlantic World. Focusing on the period that began with the major slave rebellion along the Stono River in 1739 and culminated with the 1785 incorporation of Charleston, this dissertation relies on newspapers, legislative journals, court records, and the private correspondence and business papers of merchants and planters to reveal the daily activities of waterfront workers as they interacted with each other, and with their employers and masters. -

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

David Library of the American Revolution Guide to Microform Holdings

DAVID LIBRARY OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION GUIDE TO MICROFORM HOLDINGS Adams, Samuel (1722-1803). Papers, 1635-1826. 5 reels. Includes papers and correspondence of the Massachusetts patriot, organizer of resistance to British rule, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Revolutionary statesman. Includes calendar on final reel. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 674] Adams, Dr. Samuel. Diaries, 1758-1819. 2 reels. Diaries, letters, and anatomy commonplace book of the Massachusetts physician who served in the Continental Artillery during the Revolution. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 380] Alexander, William (1726-1783). Selected papers, 1767-1782. 1 reel. William Alexander, also known as “Lord Sterling,” first served as colonel of the 1st NJ Regiment. In 1776 he was appointed brigadier general and took command of the defense of New York City as well as serving as an advisor to General Washington. He was promoted to major- general in 1777. Papers consist of correspondence, military orders and reports, and bulletins to the Continental Congress. Originals are in the New York Historical Society. [FILM 404] American Army (Continental, militia, volunteer). See: United States. National Archives. Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War. United States. National Archives. General Index to the Compiled Military Service Records of Revolutionary War Soldiers. United States. National Archives. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty and Warrant Application Files. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Rolls. 1775-1783. American Periodicals Series I. 33 reels. Accompanied by a guide. -

Henry Clinton Papers, Volume Descriptions

Henry Clinton Papers William L. Clements Library Volume Descriptions The University of Michigan Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-42cli?view=text Major Themes and Events in the Volumes of the Chronological Series of the Henry Clinton papers Volume 1 1736-1763 • Death of George Clinton and distribution of estate • Henry Clinton's property in North America • Clinton's account of his actions in Seven Years War including his wounding at the Battle of Friedberg Volume 2 1764-1766 • Dispersal of George Clinton estate • Mary Dunckerley's account of bearing Thomas Dunckerley, illegitimate child of King George II • Clinton promoted to colonel of 12th Regiment of Foot • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot Volume 3 January 1-July 23, 1767 • Clinton's marriage to Harriet Carter • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton's property in North America Volume 4 August 14, 1767-[1767] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Relations between British and Cherokee Indians • Death of Anne (Carle) Clinton and distribution of her estate Volume 5 January 3, 1768-[1768] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton discusses military tactics • Finances of Mary (Clinton) Willes, sister of Henry Clinton Volume 6 January 3, 1768-[1769] • Birth of Augusta Clinton • Henry Clinton's finances and property in North America Volume 7 January 9, 1770-[1771] • Matters concerning the 12th Regiment of Foot • Inventory of Clinton's possessions • William Henry Clinton born • Inspection of ports Volume 8 January 9, 1772-May -

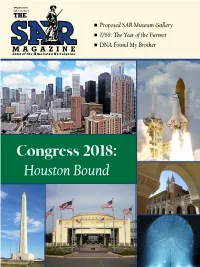

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

Inventory of the Grimke Family Papers, 1678-1977, Circa 1990S

Inventory of the Grimke Family Papers, 1678-1977, circa 1990s Addlestone Library, Special Collections College of Charleston 66 George Street Charleston, SC 29424 USA http://archives.library.cofc.edu Phone: (843) 953-8016 | Fax: (843) 953-6319 Table of Contents Descriptive Summary................................................................................................................ 3 Biographical and Historical Note...............................................................................................3 Collection Overview...................................................................................................................4 Restrictions................................................................................................................................ 5 Search Terms............................................................................................................................6 Related Material........................................................................................................................ 6 Administrative Information......................................................................................................... 7 Detailed Description of the Collection.......................................................................................8 John Paul Grimke letters (generation 1)........................................................................... 8 John F. and Mary Grimke correspondence (generation 2)................................................8 -

Allston Family Papers, 1164.00

Allston family papers, 1730-1901 SCHS# 1164.00 12/01-26 Description: 9 linear ft. (24 boxes + 2 oversized boxes) Creator: Allston family Biographical/Historical Note: Georgetown County, South Carolina family. Robert F.W. Allston (1801-1864), a plantation owner and politician, was the son of Benjamin Allston, Jr. (d. 1809) and Charlotte Anne Allston. He married Adele Petigru (sister of James Louis Petigru), and their children were: Benjamin Allston (1833-1900), Robert Allston (1834-1839), Charlotte Francis Allston, Louise Gibert Allston, William Petigru Allston, Charles Petigru Allston (1848-1922), Jane Louise Allston, who married Charles Albert Hill, Adele Allston (d. 1915), who married Arnoldus Vanderhorst (1835-1881), and Elizabeth Waties Allston (1845-1921), who married John Julius Pringle (1842-1876). John Julius Pringle was the son of John Julius Izard Pringle and Mary Izard Pringle, who later married Joel R. Poinsett (1779-1851). Elizabeth Frances Allston, a cousin of Robert F.W. Allston, married Dr. Joseph Blyth. Scope and Content: Collection contains personal and business papers of Robert F.W. Allston (1801-1864), Adele Petigru Allston, Benjamin Allston (1833-1900), Charlotte Anne Allston, Charles Petigru Allston (1848-1922), Jane Lynch Pringle, Joel R. Poinsett (1779-1851), Theodore G. Barker (b. 1832), and surveyor John Hardwick, as well as papers of the Blyth Family. Papers consist of the correspondence of Robert F.W. Allston, his wife and children, other Allston family members, members of allied families including the Lesesne, North, Petigru, Poinsett, Porcher, Pringle, Vanderhorst, and Weston families, and friends; Allston family bills and receipts, estate papers and other legal documents, land and plantation papers, plats, journals, accounts, slave records, genealogies, writings, and other items.