The Growth of the Soviet Arctic and Subarctic 29

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure- Present State And

Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure – Present State and Future Potential By Claes Lykke Ragner FNI Report 13/2000 FRIDTJOF NANSENS INSTITUTT THE FRIDTJOF NANSEN INSTITUTE Tittel/Title Sider/Pages Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure – Present 124 State and Future Potential Publikasjonstype/Publication Type Nummer/Number FNI Report 13/2000 Forfatter(e)/Author(s) ISBN Claes Lykke Ragner 82-7613-400-9 Program/Programme ISSN 0801-2431 Prosjekt/Project Sammendrag/Abstract The report assesses the Northern Sea Route’s commercial potential and economic importance, both as a transit route between Europe and Asia, and as an export route for oil, gas and other natural resources in the Russian Arctic. First, it conducts a survey of past and present Northern Sea Route (NSR) cargo flows. Then follow discussions of the route’s commercial potential as a transit route, as well as of its economic importance and relevance for each of the Russian Arctic regions. These discussions are summarized by estimates of what types and volumes of NSR cargoes that can realistically be expected in the period 2000-2015. This is then followed by a survey of the status quo of the NSR infrastructure (above all the ice-breakers, ice-class cargo vessels and ports), with estimates of its future capacity. Based on the estimated future NSR cargo potential, future NSR infrastructure requirements are calculated and compared with the estimated capacity in order to identify the main, future infrastructure bottlenecks for NSR operations. The information presented in the report is mainly compiled from data and research results that were published through the International Northern Sea Route Programme (INSROP) 1993-99, but considerable updates have been made using recent information, statistics and analyses from various sources. -

Canada GREENLAND 80°W

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-B Module 7 70°N 30°W 20°W 170°W 180° 70°N 160°W Canada GREENLAND 80°W 90°W 150°W 100°W (DENMARK) 120°W 140°W 110°W 60°W 130°W 70°W ARCTIC Essential Question OCEANDo Canada’s many regional differences strengthen or weaken the country? Alaska Baffin 160°W (UNITED STATES) Bay ic ct r le Y A c ir u C k o National capital n M R a 60°N Provincial capital . c k e Other cities n 150°W z 0 200 400 Miles i Iqaluit 60°N e 50°N R YUKON . 0 200 400 Kilometers Labrador Projection: Lambert Azimuthal TERRITORY NUNAVUT Equal-Area NORTHWEST Sea Whitehorse TERRITORIES Yellowknife NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR Hudson N A Bay ATLANTIC 140°W W E St. John’s OCEAN 40°W BRITISH H C 40°N COLUMBIA T QUEBEC HMH Middle School World Geography A MANITOBA 50°N ALBERTA K MS_SNLESE668737_059M_K.ai . S PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND R Edmonton A r Canada legend n N e a S chew E s kat Lake a as . Charlottetown r S R Winnipeg F Color Alts Vancouver Calgary ONTARIO Fredericton W S Island NOVA SCOTIA 50°WFirst proof: 3/20/17 Regina Halifax Vancouver Quebec . R 2nd proof: 4/6/17 e c Final: 4/12/17 Victoria Winnipeg Montreal n 130°W e NEW BRUNSWICK Lake r w Huron a Ottawa L PACIFIC . t S OCEAN Lake 60°W Superior Toronto Lake Lake Ontario UNITED STATES Lake Michigan Windsor 100°W Erie 90°W 40°N 80°W 70°W 120°W 110°W In this module, you will learn about Canada, our neighbor to the north, Explore ONLINE! including its history, diverse culture, and natural beauty and resources. -

Russia's Arctic Cities

? chapter one Russia’s Arctic Cities Recent Evolution and Drivers of Change Colin Reisser Siberia and the Far North fi gure heavily in Russia’s social, political, and economic development during the last fi ve centuries. From the beginnings of Russia’s expansion into Siberia in the sixteenth century through the present, the vast expanses of land to the north repre- sented a strategic and economic reserve to rulers and citizens alike. While these reaches of Russia have always loomed large in the na- tional consciousness, their remoteness, harsh climate, and inaccessi- bility posed huge obstacles to eff ectively settling and exploiting them. The advent of new technologies and ideologies brought new waves of settlement and development to the region over time, and cities sprouted in the Russian Arctic on a scale unprecedented for a region of such remote geography and harsh climate. Unlike in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of other countries, the Russian Far North is highly urbanized, containing 72 percent of the circumpolar Arctic population (Rasmussen 2011). While the largest cities in the far northern reaches of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland have maximum populations in the range of 10,000, Russia has multi- ple cities with more than 100,000 citizens. Despite the growing public focus on the Arctic, the large urban centers of the Russian Far North have rarely been a topic for discussion or analysis. The urbanization of the Russian Far North spans three distinct “waves” of settlement, from the early imperial exploration, expansion of forced labor under Stalin, and fi nally to the later Soviet development 2 | Colin Reisser of energy and mining outposts. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Beil & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 0211125 A need to know: The role of Air Force reconnaissance in war planning, 1045-1953 Farquhar, John Thomas, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1991 Copyright ©1001 by Farquhar, John Thomas. -

Taiga Plains

ECOLOGICAL REGIONS OF THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES Taiga Plains Ecosystem Classification Group Department of Environment and Natural Resources Government of the Northwest Territories Revised 2009 ECOLOGICAL REGIONS OF THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES TAIGA PLAINS This report may be cited as: Ecosystem Classification Group. 2007 (rev. 2009). Ecological Regions of the Northwest Territories – Taiga Plains. Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories, Yellowknife, NT, Canada. viii + 173 pp. + folded insert map. ISBN 0-7708-0161-7 Web Site: http://www.enr.gov.nt.ca/index.html For more information contact: Department of Environment and Natural Resources P.O. Box 1320 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9 Phone: (867) 920-8064 Fax: (867) 873-0293 About the cover: The small photographs in the inset boxes are enlarged with captions on pages 22 (Taiga Plains High Subarctic (HS) Ecoregion), 52 (Taiga Plains Low Subarctic (LS) Ecoregion), 82 (Taiga Plains High Boreal (HB) Ecoregion), and 96 (Taiga Plains Mid-Boreal (MB) Ecoregion). Aerial photographs: Dave Downing (Timberline Natural Resource Group). Ground photographs and photograph of cloudberry: Bob Decker (Government of the Northwest Territories). Other plant photographs: Christian Bucher. Members of the Ecosystem Classification Group Dave Downing Ecologist, Timberline Natural Resource Group, Edmonton, Alberta. Bob Decker Forest Ecologist, Forest Management Division, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories, Hay River, Northwest Territories. Bas Oosenbrug Habitat Conservation Biologist, Wildlife Division, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories. Charles Tarnocai Research Scientist, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. Tom Chowns Environmental Consultant, Powassan, Ontario. Chris Hampel Geographic Information System Specialist/Resource Analyst, Timberline Natural Resource Group, Edmonton, Alberta. -

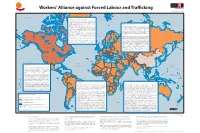

Workers' Alliance Against Forced Labour and Trafficking

165˚W 150˚W 135˚W 120˚W 105˚W 90˚W 75˚W 60˚W 45˚W 30˚W 15˚W 0˚ 15˚E 30˚E 45˚E 60˚E 75˚E 90˚E 105˚E 120˚E 135˚E 150˚E 165˚E Workers' Alliance against Forced Labour and Tracking Chelyuskin Mould Bay Grise Dudas Fiord Severnaya Zemlya 75˚N Arctic Ocean Arctic Ocean 75˚N Resolute Industrialised Countries and Transition Economies Queen Elizabeth Islands Greenland Sea Svalbard Dickson Human tracking is an important issue in industrialised countries (including North Arctic Bay America, Australia, Japan and Western Europe) with 270,000 victims, which means three Novosibirskiye Ostrova Pond LeptevStarorybnoye Sea Inlet quarters of the total number of forced labourers. In transition economies, more than half Novaya Zemlya Yukagir Sachs Harbour Upernavikof the Kujalleo total number of forced labourers - 200,000 persons - has been tracked. Victims are Tiksi Barrow mainly women, often tracked intoGreenland prostitution. Workers are mainly forced to work in agriculture, construction and domestic servitude. Middle East and North Africa Wainwright Hammerfest Ittoqqortoormiit Prudhoe Kaktovik Cape Parry According to the ILO estimate, there are 260,000 people in forced labour in this region, out Bay The “Red Gold, from ction to reality” campaign of the Italian Federation of Agriculture and Siktyakh Baffin Bay Tromso Pevek Cambridge Zapolyarnyy of which 88 percent for labour exploitation. Migrant workers from poor Asian countriesT alnakh Nikel' Khabarovo Dudinka Val'kumey Beaufort Sea Bay Taloyoak Food Workers (FLAI) intervenes directly in tomato production farms in the south of Italy. Severomorsk Lena Tuktoyaktuk Murmansk became victims of unscrupulous recruitment agencies and brokers that promise YeniseyhighN oril'sk Great Bear L. -

The Comparative Analysis of the Ruminal Bacterial Population in Reindeer (Rangifer Tarandus L.) from the Russian Arctic Zone: Regional and Seasonal Effects

animals Article The Comparative Analysis of the Ruminal Bacterial Population in Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus L.) from the Russian Arctic Zone: Regional and Seasonal Effects Larisa A. Ilina 1,*, Valentina A. Filippova 1 , Evgeni A. Brazhnik 1 , Andrey V. Dubrovin 1, Elena A. Yildirim 1 , Timur P. Dunyashev 1, Georgiy Y. Laptev 1, Natalia I. Novikova 1, Dmitriy V. Sobolev 1, Aleksandr A. Yuzhakov 2 and Kasim A. Laishev 2 1 BIOTROF + Ltd., 8 Malinovskaya St, Liter A, 7-N, Pushkin, 196602 St. Petersburg, Russia; fi[email protected] (V.A.F.); [email protected] (E.A.B.); [email protected] (A.V.D.); [email protected] (E.A.Y.); [email protected] (T.P.D.); [email protected] (G.Y.L.); [email protected] (N.I.N.); [email protected] (D.V.S.) 2 Department of Animal Husbandry and Environmental Management of the Arctic, Federal Research Center of Russian Academy Sciences, 7, Sh. Podbel’skogo, Pushkin, 196608 St. Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] (A.A.Y.); [email protected] (K.A.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: The reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) is a unique ruminant that lives in arctic areas characterized by severe living conditions. Low temperatures and a scarce diet containing a high Citation: Ilina, L.A.; Filippova, V.A.; proportion of hard-to-digest components have contributed to the development of several adaptations Brazhnik, E.A.; Dubrovin, A.V.; that allow reindeer to have a successful existence in the Far North region. These adaptations include Yildirim, E.A.; Dunyashev, T.P.; Laptev, G.Y.; Novikova, N.I.; Sobolev, the microbiome of the rumen—a digestive organ in ruminants that is responsible for crude fiber D.V.; Yuzhakov, A.A.; et al. -

Crop Production in a Northern Climate Pirjo Peltonen-Sainio, MTT Agrifood Research Finland, Plant Production, Jokioinen, Finland

Crop production in a northern climate Pirjo Peltonen-Sainio, MTT Agrifood Research Finland, Plant Production, Jokioinen, Finland CONCEPTS AND ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS THEMATIC STUDY In this thematic study northern growing conditions represent the northernmost high latitude European countries (also referred to as the northern Baltic Sea region, Fennoscandia and Boreal regions) characterized mainly as the Boreal Environmental Zone (Metzger et al., 2005). Using this classification, Finland, Sweden, Norway and Estonia are well covered. In Norway, the Alpine North is, however, the dominant Environmental Zone, while in Sweden the Nemoral Zone is represented by the south of the country as for the western parts of Estonia (Metzger et al., 2005). According to the Köppen-Trewartha climate classification, these northern regions include the subarctic continental (taiga), subarctic oceanic (needle- leaf forest) and temperate continental (needle-leaf and deciduous tall broadleaf forest) zones and climates (de Castro et al., 2007). Northern growing conditions are generally considered to be less favourable areas (LFAs) in the European Union (EU) with regional cropland areas typically ranging from 0 to 25 percent of total land area (Rounsevell et al., 2005). Adaptation is the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects, in order to moderate harm or exploit beneficial opportunities (IPCC, 2012). Adaptive capacity is shaped by the interaction of environmental and social forces, which determine exposures and sensitivities, and by various social, cultural, political and economic forces. Adaptations are manifestations of adaptive capacity. Adaptive capacity is closely linked or synonymous with, for example, adaptability, coping ability and management capacity (Smit and Wandel, 2006). -

Fresh Water and Its Role in the Arctic Marine System

PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences RESEARCH ARTICLE Freshwater and its role in the Arctic Marine System: Sources, 10.1002/2015JG003140 disposition, storage, export, and physical and biogeochemical Special Section: consequences in the Arctic and global oceans Arctic Freshwater Synthesis E. C. Carmack1, M. Yamamoto-Kawai2, T. W. N. Haine3, S. Bacon4, B. A. Bluhm5, C. Lique6,7, H. Melling1, I. V. Polyakov8, F. Straneo9, M.-L. Timmermans10, and W. J. Williams1 Key Points: • The Arctic Ocean Freshwater System 1Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Sidney, British Columbia, Canada, 2Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, has major intra-Arctic and extra-Arctic 3 4 effects Tokyo, Japan, Earth and Planetary Sciences, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, National • The Arctic Ocean Freshwater System Oceanography Centre, Southampton, UK, 5Department of Marine and Arctic Biology, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, regulates and constrains physical and Tromsø, Norway, 6Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, 7Now at Laboratoire de Physique des biogeochemical processes Océans, Ifremer, Plouzané, France, 8International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska, • Changes in the Arctic Ocean 9 10 Freshwater System are expected in USA, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA, Department of Geology and Geophysics, the future with substantial impacts Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA Abstract The Arctic Ocean -

Load Article

Arctic and North. 2018. No. 33 55 UDC [332.1+338.1](985)(045) DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2018.33.66 The prospects of the Northern and Arctic territories and their development within the Yenisei Siberia megaproject © Nikolay G. SHISHATSKY, Cand. Sci. (Econ.) E-mail: [email protected] Institute of Economy and Industrial Engineering of the Siberian Department of the Russian Academy of Sci- ences, Kransnoyarsk, Russia Abstract. The article considers the main prerequisites and the directions of development of Northern and Arctic areas of the Krasnoyarsk Krai based on creation of reliable local transport and power infrastructure and formation of hi-tech and competitive territorial clusters. We examine both the current (new large min- ing and processing works in the Norilsk industrial region; development of Ust-Eniseysky group of oil and gas fields; gasification of the Krasnoyarsk agglomeration with the resources of bradenhead gas of Evenkia; ren- ovation of housing and public utilities of the Norilsk agglomeration; development of the Arctic and north- ern tourism and others), and earlier considered, but rejected, projects (construction of a large hydroelectric power station on the Nizhnyaya Tunguska river; development of the Porozhinsky manganese field; place- ment of the metallurgical enterprises using the Norilsk ores near Lower Angara region; construction of the meridional Yenisei railroad and others) and their impact on the development of the region. It is shown that in new conditions it is expedient to return to consideration of these projects with the use of modern tech- nologies and organizational approaches. It means, above all, formation of the local integrated regional pro- duction systems and networks providing interaction and cooperation of the fuel and raw, processing and innovative sectors. -

Siberian Expectations: an Overview of Regional Forest Policy and Sustainable Forest Management

Siberian Expectations: An Overview of Regional Forest Policy and Sustainable Forest Management July 2003 World Forest Institute Portland, Oregon, USA Authors: V.A. Sokolov, I.M. Danilin, I.V. Semetchkin, S.K. Farber,V.V. Bel'kov,T.A. Burenina, O.P.Vtyurina,A.A. Onuchin, K.I. Raspopin, N.V. Sokolova, and A.S. Shishikin Editors: A. DiSalvo, P.Owston, and S.Wu ABSTRACT Developing effective forest management brings universal challenges to all countries, regardless of political system or economic state. The Russian Federation is an example of how economic, social, and political issues impact development and enactment of forest legislation. The current Forest Code of the Russian Federation (1997) has many problems and does not provide for needed progress in the forestry sector. It is necessary to integrate economic, ecological and social forestry needs, and this is not taken into account in the Forest Code. Additionally, excessive centralization in forest management and the forestry economy occurs. This manuscript discusses the problems facing the forestry sector of Siberia and recommends solutions for some of the major ones. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research for this book was supported by a grant from the International Research and Exchanges Board with funds provided by the Bureau of Education and Cultural Affairs, a division of the United States Department of State. Neither of these organizations are responsible for the views expressed herein. The authors would particularly like to recognize the very careful and considerate reviews, including many detailed editorial and language suggestions, made by the editors – Angela DiSalvo, Peyton Owston, and Sara Wu. They helped to significantly improve the organization and content of this book. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country.