JH Thomas and the Rise of Labour in Derby, 1880

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberals, Labour and Leicester - the 1913 By-Election in Local and National Perspective by John Pasiecznik

Liberals, Labour and Leicester - The 1913 By-Election in Local and National Perspective by John Pasiecznik One of Leicester's most dramatic election battles took place in June 1913 when the Liberals, Conservatives and British Socialist Party fought a by-election in the borough. Most attention was focused on the fledgling Labour Party which did not contest the seat. Voting on June 27th took place amid accusations of treachery aimed mostly at Labour Party Secretary, Ramsey MacDonald - who held the second Leicester seat - and who was a member of the Labour Party National Executive Committee which decided not to run a candidate. As this article reveals, Labour was in a dilemma. Following the national Lib-Lab Pact of 1903, the Liberals agreed not to put up a second candidate in Leicester which enabled future Labour Party Leader Ramsey MacDonald to become an MP. But ten years on should Labour still adhere to the pact? If the second seat was contested, the agreement would end; if Labour did not fight, the party could not claim to be truly independent of all other parties. The singular events of the by-election in the double-member seat of Leicester forms part of the city's rich political history. Leicester was a Radical stronghold in Victorian Britain. The Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 ushered in Whig supremacy. The transfer of power was total and long-lasting. Except for the 1861 by-election, the Whigs (later the Liberals) won every seat in the double member constituency in a general or by-election from 1837 to 1895. -

The Membership of the Independent Labour Party, 1904–10

DEI AN HOP KIN THE MEMBERSHIP OF THE INDEPENDENT LABOUR PARTY, 1904-10: A SPATIAL AND OCCUPATIONAL ANALYSIS E. P. Thompson expressed succinctly the prevailing orthodoxy about the origins of the Independent Labour Party when he wrote, in his homage to Tom Maguire, that "the ILP grew from bottom up".1 From what little evidence has been available, it has been argued that the ILP was essentially a provincial party, which was created from the fusion of local political groups concentrated mainly on an axis lying across the North of England. An early report from the General Secretary of the party described Lancashire and Yorkshire as the strongholds of the movement, and subsequent historical accounts have supported this view.2 The evidence falls into three categories. In the first place labour historians have often relied on the sparse and often imperfect memoirs of early labour and socialist leaders. While the central figures of the movement have been reticent in their memoirs, very little literature of any kind has emerged from among the ordinary members of the party, and as a result this has often been a poor source. The official papers of the ILP have been generally more satisfactory. The in- evitable gaps in the annual reports of the party can be filled to some extent from party newspapers, both local and national. There is a formality, nevertheless, about official transactions which reduces their value. Minute books reveal little about the members. Finally, it is possible to cull some information from a miscellany of other sources; newspapers, electoral statistics, parliamentary debates and reports, and sometimes the memoirs of individuals whose connection 1 "Homage to Tom Maguire", in: Essays in Labour History, ed. -

"The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats": the Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-193

"The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats": The Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-1931 TAYLOR, Antony <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4635-4897> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17408/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version TAYLOR, Antony (2018). "The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats": The Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-1931. Historical Research, 91 (254), 723-743. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk ‘The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats’: The Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-1931 Recent years have seen an increased interest in the partisan uses of the political past by British political parties and by their apologists and adherents. This trend has proved especially marked in relation to the Labour party. Grounded in debates about the historical basis of labourism, its ‘true’ nature, the degree to which sacred elements of the past have been discarded, marginalised, or revived as part of revisions to the labour platform and through changes of leader, the past has become a contentious area of debate for those interested in broader currents of reform and their relationship to the progressive movements that fed through into the platform of the early twentieth-century Labour party. Contesting traditional notions of labourism as an undifferentiated and unimaginative creed, this article re-examines the political traditions that informed the Labour platform and traces the broader histories and mythologies the party drew on to establish the basis for its moral crusade. -

(C) Crown Copyright Catalogue Reference:CAB/23/67 Image

(c) crown copyright Catalogue Reference:CAB/23/67 Image Reference:0022 ("THIS DOCUMENT IS TH PROPERTY OF HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT) SECRET. Gopy No. C^) . CABINET Kl CONCLUSIONS of a Meeting of the Cabinet held at 10, Downing Street, S.W.1., on MONDAY, August 2ifth, 1931, at 12 noon. PRESENT: - The Right Hon. J. Ramsay MaeDonald, M.P. , Prime Minister. (in the Chair). The Right Hon. The Right Hon. Philip Snowden, M.P., Arthur Henderson, M.P., Chancellor of the Secretary of State for Exchequer. Foreign Affairs. The Right Hon. The Right Hon. J.H. Thomas, M.P., Lord Passfield, Secretary of State for Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs. the Colonies. The Right Hon. The Right Hon. Lord Sankey, G.B.E., J.R, Clynes, M.P., Lord Chancellor. Secretary of State for Home Affairs. The Right Hon. The Right Hon. W. Wedgwood Benn, D.S.O., Tom Shaw, C.B.E.,M.P., D.F.C.,M.P., Secretary of Secretary of State for State for India. War. The Right Hon. The Right Hon. Lord Amulree, G.B.B.,K.C, Arthur Greenwood, M.P., Secretary of State for Minister of Health. Air. The Right Hon. The Right Hon. *- Margaret Bondfield, M.P., Christopher Addison, M.P., Minister of Labour. Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries. iThe Right Hon. The Right Hon. H.B. Lees-Smith, M.P., W. Graham, M.P., President of the Board President of the of Education. Board of Trade. IThe Right Hon. The Right Hon. A.V. Alexander, M.P., William Adamson, M.P., First Lord of the Secretary of State for Admiralty. -

File Is Composed of the Comfortable Class

The English Radical Tradition and the British Left 1885-1945 ENDERBY, John Stephen Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26096/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26096/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. The English Radical Tradition and the British Left 1885-1945 by John Stephen Enderby A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 I hereby declare that: 1. I have not been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University's policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acknowledged. 4. The work undertaken towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy. -

Cotton and the Community: Exploring Changing Concepts of Identity and Community on Lancashire’S Cotton Frontier C.1890-1950

Cotton and the Community: Exploring Changing Concepts of Identity and Community on Lancashire’s Cotton Frontier c.1890-1950 By Jack Southern A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of a PhD, at the University of Central Lancashire April 2016 1 i University of Central Lancashire STUDENT DECLARATION FORM I declare that whilst being registered as a candidate of the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another aware of the University or other academic or professional institution. I declare that no material contained in this thesis has been used for any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work. Signature of Candidate ________________________________________________ Type of Award: Doctor of Philosophy School: Education and Social Sciences ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores the evolution of identity and community within north east Lancashire during a period when the area gained regional and national prominence through its involvement in the cotton industry. It examines how the overarching shared culture of the area could evolve under altering economic conditions, and how expressions of identity fluctuated through the cotton industry’s peak and decline. In effect, it explores how local populations could shape and be shaped by the cotton industry. By focusing on a compact area with diverse settlements, this thesis contributes to the wider understanding of what it was to live in an area dominated by a single industry. The complex legacy that the cotton industry’s decline has had is explored through a range of settlement types, from large town to small village. -

Anti-Fascism in a Global Perspective

ANTI-FASCISM IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE Transnational Networks, Exile Communities, and Radical Internationalism Edited by Kasper Braskén, Nigel Copsey and David Featherstone First published 2021 ISBN: 978-1-138-35218-6 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-138-35219-3 (pbk) ISBN: 978-0-429-05835-6 (ebk) Chapter 5 ‘Make Scandinavia a bulwark against fascism!’: Hitler’s seizure of power and the transnational anti-fascist movement in the Nordic countries Kasper Braskén (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) This OA chapter is funded by the Academy of Finland (project number 309624) 5 ‘MAKE SCANDINAVIA A BULWARK AGAINST FASCISM!’ Hitler’s seizure of power and the transnational anti-fascist movement in the Nordic countries Kasper Braskén On a global scale, Hitler’s seizure of power on 30 January 1933 provided urgent impetus for transnational anti-fascist conferences and rallies. One of the first Eur- opean, but almost completely overlooked major conferences was organised in Copenhagen in mid-April 1933 in the form of a Scandinavian Anti-Fascist Con- ference. This formed a transnational meeting point of European and especially Scandinavian workers and intellectuals that provided an important first response to developments in Germany. The chapter will use the Scandinavian conference as a prism to look back at anti-fascist activism in the Nordic countries during the preceding years, and to then follow its transformation after 1933. It will contribute to the global analysis of the transition period of communist-led anti-fascism from the sectarian class-against-class line to the inception of the popular front period in 1935. What were these largely overlooked, first anti-fascist articulations in Europe, and how were they connected to the rising transnational and global anti-fascist mobi- lisation coordinated in Paris and London? As we shall see, on the one hand Hitler’s seizure of power vitalised anti-fascism in Scandinavia but paradoxically, on the other, it further sharpened the communist critique of reformist social democracy and empowered social democratic anti-communism. -

Clement Attlee Was Born on 3 January 1883 in Putney, the Seventh of Eight Children

P R O F I L E Clement Attlee was born on 3 January 1883 in Putney, the seventh of eight children. His father, Henry Attlee, was a solicitor and senior partner in the firm of Druces and Attlee, whose offices were in the Middle Temple. After being home-schooled, Attlee was educated at the preparatory school Northaw Place and then Haileybury College, both in Hertfordshire. At Haileybury, which had a strong military ethos, Attlee became an enthusiastic member of the Volunteer Rifle Corps. After leaving Haileybury in 1901 Attlee went on to University College, Oxford, where he studied Modern History. He specialised in Italian and Renaissance history and graduated in 1904 with a second-class degree. After leaving Oxford Attlee followed in his father’s footsteps and entered the legal profession, although without any great enthusiasm for it. He had been admitted to the Inner Temple on 30 January 1904, and in the autumn of that year entered the Lincoln’s Inn chambers of Sir Philip Gregory. His father’s connections meant he had already C L E M E N T dined at the Inner Temple; he was called to the Bar in March 1906. In October 1905, Attlee accompanied his brother Laurence to the A T T L E E Haileybury Club, a club in Stepney, East London for working-class boys, run by former Haileybury College pupils. It was connected to B O R N 1 8 8 3 the Territorial Army, and volunteers were expected to become non- D I E D 1 9 6 7 commissioned officers. -

Fabianism, Permeation and Independent Labour

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Fabianism, Permeation and Independent Labour Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3s4368vt Journal Historical Journal, 39 Author Bevir, Mark Publication Date 1996 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California FABIANISM, PERMEATION AND INDEPENDENT LABOUR By MARK BEVIR Department of Politics The University Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU 1 ABSTRACT The leading Fabians held different versions of permeation: Shaw saw permeation in terms of weaning the Radicals away from the Liberal Party, so he favoured an independent party; Webb defined permeation in terms of the giving of expert advice to a political elite without any need for a new party. These varieties of permeation can be traced in the individual and collective actions of the Fabians, and, in particular, in their attitude to the formation of the Independent Labour Party (I.L.P.). The Fabians did not simply promote the I.L.P. nor did they simply oppose the I.L.P. 2 FABIANISM, PERMEATION AND INDEPENDENT LABOUR Introduction Historians have long debated the extent to which the Fabian Society acted as John the Baptist to the Labour Party. The Fabians presented themselves as the single most important group in winning for socialism a foothold on British soil: they replaced the alien creed of Marxism with a gradualist constitutionalism suited to British traditions, and their evolutionary brand of socialism precipitated the Labour Party, albeit by way of the Independent Labour Party (I.L.P.). 1 Recent years, however, have seen the triumph of revisionists, inspired in large part by the scholarship of Professors Hobsbawm and McBriar, who dismiss the Fabians as vehemently as Shaw once extolled their virtues. -

Anti-Fascism in a Global Perspective

ANTI-FASCISM IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE Transnational Networks, Exile Communities, and Radical Internationalism Edited by Kasper Braskén, Nigel Copsey and David Featherstone First published 2021 ISBN: 978-1-138-35218-6 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-138-35219-3 (pbk) ISBN: 978-0-429-05835-6 (ebk) Chapter 10 ‘Aid the victims of German fascism!’: Transatlantic networks and the rise of anti-Nazism in the USA, 1933–1935 Kasper Braskén (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) This OA chapter is funded by the Academy of Finland (project number 309624) 10 ‘AID THE VICTIMS OF GERMAN FASCISM!’ Transatlantic networks and the rise of anti-Nazism in the USA, 1933–1935 Kasper Braskén Anti-fascism became one of the main causes of the American left-liberal milieu during the mid-1930s.1 However, when looking back at the early 1930s, it seems unclear as to how this general awareness initially came about, and what kind of transatlantic exchanges of information and experiences formed the basis of a rising anti-fascist consensus in the US. Research has tended to focus on the latter half of the 1930s, which is mainly concerned with the Communist International’s (Comintern) so-called popular front period. Major themes have included anti- fascist responses to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, the strongly felt soli- darity with the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), or the slow turn from an ‘anti-interventionist’ to an ‘interventionist/internationalist’ position during the Second World War.2 The aim of this chapter is to investigate two communist-led, international organisations that enabled the creation of new transatlantic, anti-fascist solidarity networks only months after Hitler’s rise to power in January 1933. -

Chronological Index of Miscellaneous Anti-Fascist Pamphlets and Leaflets

Chronological index of miscellaneous anti-fascist pamphlets and leaflets 1925-1945 Leaflets: No justice for Labour!: fascists admit robbery with violence and are Fascism Box 8 discharged! (1925) The fruits of fascism (Labour Party, 1933) Labour Party Box 23 The spotlight on the Blackshirts: who are these Blackshirts? (Labour Labour Party Box 23 Party, 1934) (Labour Leaflet 29) Trade union officials arrested: branches, area committees dissolved Fascism Box 8 (Anti-Fascist Relief Committee, ca. 1936) Do you know these facts about Mosley and his Fascists? (Woburn Press, Fascism Box 8 ca. 1936 Jewish People's Council against Fascism and Anti-Semitism and the Fascism Box 2 Board of Deputies (Jewish People's Council against Fascism and Anti- Semitism, ca. 1936) Fascism: fight it now (Labour Research Department, 1937) Labour Research Department The BUF and anti-semitism: an exposure (CH Lane, ca. 1937) Fascism Box 1 Britain's fifth column: a plain warning! (Anchor Press, 1940) Fascism Box 1 The menace of fascism! (Kersal Jewish Discussion Circle, no date) Fascism Box 3 Pamphlets: The truth about the New Party, by Cecil Melville (Lawrence and Wishart, Fascism Box 8 1931) The burning of the Reichstag: official findings of the Legal Commission of Fascism Box 1 Inquiry Sep 1933 (Relief Committee of the Victims Of German Fascism, 1933) Democracy and fascism: a reply to the Labour manifesto on "Democracy Communist Party of versus dictatorship" by R Palme Dutt (Communist Party of Great Britain, Great Britain Box 3 ca. 1933) Feed the children: what is being done to relieve the victims of the fascist Fascism Box 1 regime by Ellen Wilkinson (International Committee for the Relief of the Victims of German Fascism, ca. -

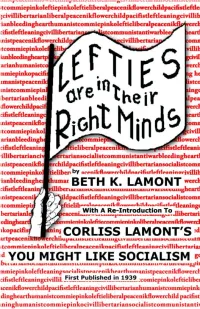

LEFTIES ARE in THEIR RIGHT MINDS Part One

LEFTIES ARE IN THEIR RIGHT MINDS LEFTIES ARE IN THEIR RIGHT MINDS Part One By Beth K. Lamont April 2009 And A Re-Introduction to Corliss Lamont’s You Might Like Socialism First Published in 1939 HALF-MOON FOUNDATION, INC. The Half-Moon Foundation was formed to promote enduring inter- national peace, support for the United Nations, the conservation of our country’s natural environment, and to safeguard and extend civil liberties as guaranteed under the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Lefties Are In Their Right Minds Copyright © 2009 by Beth K. Lamont All rights reserved. Published by Half-Moon Foundation, Inc. ISBN 978-0-578-00782-3 You Might Like Socialism: A Way of Life for Modern Man Copyright © 1939 by Corliss Lamont Originally published by Modern Age Books, Inc. New York, NY Visit the Corliss Lamont Web site http://www.corliss-lamont.org/ Printed in the United States of America Preface Actually, there’s no need for you to read this book at all! The title sums up its whole thesis. When I say Lefties Are In Their Right Minds, I’m trying to give a whimsical approach to a very serious subject. The Righties of this world, who still believe that their might makes them right, have been wrong for too long. That’s why I’m urging: Lefties, it’s you who are right! Check-out a true Leftie-Life-Line: Pacifica Radio, especially its New York Station, @ FM 99.5 WBAI! We're gathering strength! We need to Unite! And what perfect timing. Unbridled Capitalism is in disgrace; I picture rowdy, irresponsible teenagers behaving badly and Big Daddy having to bail them out of jail.