South Sudan Rapid Response Deterioration of Protection and Human Rights Environment 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Western Equatoria Infographic V6 Final

Joint report by United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and Ofce of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Report on violations and abuses against civilians in Gbudue April–August and Tambura States, Western Equatoria 2018 INTRODUCTION This report is jointly published by the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and the Ofce of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), pursuant to United Nations Security Council resolution 2406 (2018). The report presents the ndings of an investigation conducted by the UNMISS Human Rights Division (UNMISS HRD) into violations and abuses of international human rights law and violations of international humanitarian law reportedly committed by the pro-Machar Sudan People’s Liberation Army in Opposition (SPLA-IO (RM)) and the Government’s Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) against civilians in the states of Gbudue and Tambura, in Western Equatoria, between April and August 2018. The report documents the plight of civilians in the Western Equatoria region of South Sudan, where increased violence and attacks between April and August 2018 saw nearly 900 people abducted, including 505 women, and forced into sexual slavery or combat, and over 24,000 displaced from their homes. The report identies three SPLA-IO commanders who may bear the greatest responsibility for the violence committed against the civilian population in Western Equatoria during the period under consideration. HRD employed the standard of proof of reasonable grounds to believe in making factual determinations about the violations and abuses incidents, and patterns of conduct of the perpetrators. Unless specically stated, all information in the report has been veried using several independent, credible and reliable sources, in accordance with OHCHR’s human rights monitoring and investigation methodology. -

Secretary-General's Report on South Sudan (September 2020)

United Nations S/2020/890 Security Council Distr.: General 8 September 2020 Original: English Situation in South Sudan Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2514 (2020), by which the Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) until 15 March 2021 and requested me to report to the Council on the implementation of the Mission’s mandate every 90 days. It covers political and security developments between 1 June and 31 August 2020, the humanitarian and human rights situation and progress made in the implementation of the Mission’s mandate. II. Political and economic developments 2. On 17 June, the President of South Sudan, Salva Kiir, and the First Vice- President, Riek Machar, reached a decision on responsibility-sharing ratios for gubernatorial and State positions, ending a three-month impasse on the allocations of States. Central Equatoria, Eastern Equatoria, Lakes, Northern Bahr el-Ghazal, Warrap and Unity were allocated to the incumbent Transitional Government of National Unity; Upper Nile, Western Bahr el-Ghazal and Western Equatoria were allocated to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO); and Jonglei was allocated to the South Sudan Opposition Alliance. The Other Political Parties coalition was not allocated a State, as envisioned in the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan, in which the coalition had been guaranteed 8 per cent of the positions. 3. On 29 June, the President appointed governors of 8 of the 10 States and chief administrators of the administrative areas of Abyei, Ruweng and Pibor. -

Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the Market of Mayen Rual South Sudan Customary Authorities Project

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT WARTIME TRADE AND THE RESHAPING OF POWER IN SOUTH SUDAN LEARNING FROM THE MARKET OF MAYEN RUAL SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities pROjECT Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the market of Mayen Rual NAOMI PENDLE AND CHirrilo MADUT ANEI Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, 159/163 Marlborough Road, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHORS Naomi Pendle is a Research Fellow in the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa, London School of Economics. Chirrilo Madut Anei is a graduate of the University of Bahr el Ghazal and is an emerging South Sudanese researcher. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. The SSCA Project is supported by the Swiss Government. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PUBLICATIONS AND PROGRAMME MANAGER: Magnus Taylor EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-56-2 COVER: Chief Morris Ngor RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018 Cover image © Silvano Yokwe Alison Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

2011 South Sudan Education Statistical Booklet

Education Statistics for Western Equatoria Government of Republic of South Sudan Ministry of General Education and Instruction State Statistical Booklet Western Equatoria Republic of South Sudan Ministry of General Education and Instruction Directorate of Planning and Budgeting Department of Data and Statistics Education Management Information Systems Unit Juba, South Sudan www.goss.org © Ministry of General Education and Instruction 2012 This publication may be used as a part or as a whole, provided that the MoGEI is acknowledged as the source of information. This publication has been produced with financial and technical support from UNICEF, FHI360, and SCiSS. For inquiries or requests, please use the following contact information: George Mogga / Director for Planning and Budgeting / [email protected] Fahim Akbar / Senior EMIS Advisor / [email protected] Moses Kong / EMIS Officer / [email protected] Paulino Kamba / EMIS Officer / [email protected] Joanes Odero / Programme Associate / [email protected] Deng Chol Deng / Programme Associate / [email protected] 1 Foreword Message from Minister Joseph Ukel Abango On behalf of the Ministry of General Education and Instruction (MoGEI), I am pleased for the fifth education census data for the Republic of South Sudan (RSS). The collection and consolidation of the Education Management Information System (EMIS) have come a long way since the baseline assessment, or the Rapid Assessment of Learning Spaces (RALS) conducted in 2006. RALS covered less than half of the primary schools operating in the country at the time. By 2011, data from pre-primary, primary, secondary, an Alternative Education Systems (AES), and technical and vocational education and training (TVET) schools, centres, and institutes were collected. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

09.04.20 South Sudan Program

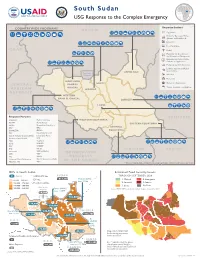

South Sudan USG Response to the Complex Emergency COUNTRYWIDE PROGRAMS Response Sectors: SUDAN Agriculture Economic Recovery, Market Systems, and Livelihoods Education Food Assistance CHAD Health Humanitarian Coordination and Information Management Humanitarian Policy, Studies, Analysis, or Application Multipurpose Cash Assistance Logistics Support and Relief Commodities Abyei Area- UPPER NILE Disputed* Nutrition Protection NORTHERN UNITY Shelter and Settlements CENTRAL BAHR EL GHAZAL Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene AFRICAN WARRAP REPUBLIC WESTERN BAHR EL GHAZAL JONGLEI LAKES Response Partners: ETHIOPIA AAH/USA Mentor Initiative WESTERN EQUATORIA ACTED Mercy Corps EASTERN EQUATORIA ALIMA Nonviolent Peaceforce ARC NRC CENTRAL CONCERN OCHA EQUATORIA CRS Relief International Danish Refugee Council (DRC) Samaritan's Purse Doctors of the World SCF FAO Tearfund ICRC UNHCR IFRC UNICEF IMC VSF/G UGANDA KENYA Internews WFP (UNHAS) IOM WFP DEMOCRATIC IRC WHO REPUBLIC Lutheran World Federation World Vision, Inc. (USA) MEDAIR, SWI WRI OF THE CONGO * Final sovereignty status of Abyei Area pending negotiations between South Sudan and Sudan. IDPs in South Sudan Estimated Food Security Levels # By State " UNMISS IDP Site SUDAN THROUGH SEPTEMBER 2020 # Malakal UNMISS 1: Minimal 4: Emergency 60,000 - 100,000 IDP Site ~813,300 base: 27,900 100,000 - 150,000 Host Communities # 2: Stressed 5: Famine 150,000 - 200,000 ## 3: Crisis No Data Abyei Area - 200,000 - 250,000 Bentiu UNMISS Disputed # Source: FEWS NET, South Sudan Outlook, August - September 2020 base: 111,800 ~9,300 ## ## # # ~233,800# # ## # ##"# # # #"# # ### # #~76,400 # # # ~226,000 # # # # # # # ### Wau UNMISS # ETHIOPIA ##~246,700 # base: 10,000 #"## # ~71,200 ~346,300 # # ~207,200 # ~187,200 # # Bor C.A.R. UNMISS # ~2,600 #"# base: # # 1,900 ## # ~70,900 ## # # # ~60,100 Map reflects FEWS NET # ##"# # # # food security projections # Refugees in Neighboring Countries #~220,800 # at the area level. -

The Republic of South Sudan Request for an Extension of the Deadline For

The Republic of South Sudan Request for an extension of the deadline for completing the destruction of Anti-personnel Mines in mined areas in accordance with Article 5, paragraph 1 of the convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Antipersonnel Mines and on Their Destruction Submitted at the 18th Meeting of the State Parties Submitted to the Chair of the Committee on Article 5 Implementation Date 31 March 2020 Prepared for State Party: South Sudan Contact Person : Jurkuch Barach Jurkuch Position: Chairperson, NMAA Phone : (211)921651088 Email : [email protected] 1 | Page Contents Abbreviations 3 I. Executive Summary 4 II. Detailed Narrative 8 1 Introduction 8 2 Origin of the Article 5 implementation challenge 8 3 Nature and extent of progress made: Decisions and Recommendations of States Parties 9 4 Nature and extent of progress made: quantitative aspects 9 5 Complications and challenges 16 6 Nature and extent of progress made: qualitative aspects 18 7 Efforts undertaken to ensure the effective exclusion of civilians from mined areas 21 # Anti-Tank mines removed and destroyed 24 # Items of UXO removed and destroyed 24 8 Mine Accidents 25 9 Nature and extent of the remaining Article 5 challenge: quantitative aspects 27 10 The Disaggregation of Current Contamination 30 11 Nature and extent of the remaining Article 5 challenge: qualitative aspects 41 12 Circumstances that impeded compliance during previous extension period 43 12.1 Humanitarian, economic, social and environmental implications of the -

Download (PDF, 514.70

SOUTH SUDAN Overview of spontaneous refugee returns 31 August 2019 Spontaneous refugee returnees by Country of Asylum 209,071 Overall Current Month Reported Spontaneous Uganda 92,093 44.0% Refugee Returnees* 3,096 Sudan 54,108 25.9% 15,945 recorded in August 2019 10,634 24.0% Ethiopia 50,220 2,332,097 South Sudanese 1,677 5,215 2.5% Refugees in host countries Kenya as of 30 June 2019 49 4,599 2.2% DRC ** 489 855,962 833,784 2,800 1.3% CAR ** 422,240 36 0.1% 118,067 102,044 Other Sudan Uganda Ethiopia Kenya DRC** ** CAR: Central African Republic; DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo 2019 spontaneous refugee return trend (1 Jan - 31 Aug): 73,085 *** Spontaneous0K refugee returnees50K by State100K of arrival 20,431 Eastern Equatoria 61,430 15,945 Jonglei 44,024 Unity 37,763 Upper Nile 23,919 9,262 Central Equatoria 18,981 6,000 6,480 9,538 4,600 Lakes 15,407 829 Western Bhar Ghazal 3,793 Western Equatoria 2,864 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Northern Bahr Ghazal 470 Warrap 420 ***Historical data might change retroactively due to late reporting and time required to triangulate information Spontaneous Refugee Returnees by county MANYO 11,350 SUDAN RENK 939 MELUT 54 MABAN FASHODA 19,524 UNITY 488 ABYEI 1,052 Upper Nile PARIANG MALAKAL UpperUpperUPPER NileNile ABIEMNHOM PANYIKAG 153 706 NILE 14 1,010 BALIET AWEIL NORTH RUBKONA 211 LONGOCHUK GUIT 293 TWIC MAYOM 18,351 1,077 4,877 319 5,069 FANGAK AWEIL WEST NORTHERN 256 LUAKPINY/NASIR RAGA 43 Northern Bahr el 27,860 1,090 BAHR EL GHAZAL KOCH MAIWUT 1,144 Ghazal GOGRIAL WEST NYIROL ULANG 5,202Unity -

Distribution of Ethnic Groups in Southern Sudan Exact Representationw Ohf Iteh En Isleituation Ins Tehnen Acrountry

Ethnic boundaries shown on this map are not an Distribution of Ethnic Groups in Southern Sudan exact representationW ohf iteh eN isleituation inS tehnen aCrountry. The administrative units and their names shown on this map do not imply White acceptance or recognition by the Government of Southern Sudan. Blue ") State Capitals This map aims only to support the work of the Humanitarian Community. Nile Renk Nile Sudan Renk Admin. Units County Level Southern Darfur Southern Shilluk Berta Admin. Units State Level Kordofan Manyo Berta Country Boundary Manyo Melut International Boundaries Shilluk Maban Sudan Fashoda Dinka (Abiliang) Abyei Pariang Upper Nile Burum Malakal Data Sources: National and State Dinka (Ruweng) ") boundaries based on Russian Sudan Malakal Baliet Abiemnhom Panyikang Map Series, 1:200k, 1970-ties. Rubkona Guit County Boundaries digitized based on Aweil North Statistical Yearbook 2009 Aweil East Twic Mayom ") Nuer (Jikany) Canal (Khor Fulus) Longochuk Southern Sudan Commission for Census, Dinka (Twic WS) Nuer (Bul) Statistics and Evaluation - SSCCSE. Fangak Dinka (Padeng) Digitized by IMU OCHA Southern Sudan Aweil West Dinka (Malual) Nuer (Lek) Gogrial East Unity Nuer (Jikany) Northern Bahr el Ghazal ") Luakpiny/Nasir Aweil Maiwut Aweil South Raga Koch Gogrial West Nuer (Jegai) Nyirol Ulang Nuer (Gawaar) Aweil Centre Warrap ") Tonj North Ayod Kwajok Mayendit Leer Dinka (Rek) Fertit Chad Nuer (Adok) Nuer (Lou) Jur Chol Tonj East ") Wau Akobo Western Bahr el Ghazal Nuer (Nyong) Dinka (Hol) Uror Duk Jur River Rumbek North Panyijar -

Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA)

PERMANENTPERMANENT COURT COURT OF OF ARBITRATION ARBITRATION ININTHETHE MATTER MATTER OF OFANANARBITRATIONARBITRATION BEFORE BEFORE A ATRIBUNALTRIBUNAL CONSTITUTEDCONSTITUTEDININACCORDANCEACCORDANCEWITHWITHARTICLEARTICLE55OFOFTHETHE ARBITRATIONARBITRATION AGREEMENTAGREEMENT BETWEENBETWEEN THETHE GOVERNMENTGOVERNMENT OFOF SUDANSUDAN ANDAND THETHE SUDANSUDAN PEOPLE’SPEOPLE’S LIBERATIONLIBERATION MOVEMENT/ARMYMOVEMENT/ARMY ON ON DELIMITING DELIMITING ABYEI ABYEI AREA AREA BETWEEN:BETWEEN: GOVERNMENTGOVERNMENT OF OF SUDAN SUDAN andand SUDANSUDAN PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S LIBERATION LIBERATION MOVEMENT/ARMY MOVEMENT/ARMY MEMORIALMEMORIAL OF OF THE THE GOVERNMENT GOVERNMENT OF OF SUDAN SUDAN VOLUMEVOLUME II II ANNEXESANNEXES 1818 DECEMBER DECEMBER 2008 2008 Figure 1 The Area of the Bahr el Arab Figure 1 The Area of the Bahr el Arab ii ii Table of Contents Glossary Personalia List of Figures paras 1. Introduction 1-38 A. Geographical Outline 1-3 B. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement and the Boundaries of 1956 4-5 C. Abyei and the “Abyei Area” 6-9 D. Origins of the Dispute Submitted to the Tribunal 10-15 E. The Task of this Tribunal 16-36 (i) Key Provisions 16-18 (ii) The Dispute submitted to Arbitration 19-20 (iii) The Excess of Mandate 21-21 (iv) The Area Transferred 22-36 (a) The Territorial Dimension 22-30 (b) The Temporal Dimension 31-33 (c) The Applicable Law 34-35 (d) Conclusion 36-36 F. Outline of this Memorial 37-38 2. The Meaning of the Formula 39-56 A. Introduction 39-40 B. The Addis Ababa Agreement of 1972 41-42 C. Discussions leading to the CPA and the Abyei Protocol 43-55 D. Conclusions 56-56 3. The ABC Process 57-92 A. Introduction 57-58 B. -

1. Humanitarian Situation Highlights

SOUTH SUDAN Emergency preparedness and Humanitarian Action (EHA) Week 39 (24 TH -30th) 2012 Office f or the Republic of South Sudan Highlights 1. Humanitarian situation The overall Security situation remained stable in the country although some rumors of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) movement at the border line with Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) & Central African Republic (CAR) were recorded . Reports of Rebel Militia Groups in Jonglei states were also recorded this week with no c asualties but with displacements. The continued influx of refugees in to Maban county is straining the humanitarian operation. There are currently 105,000 refugees in Maban County, 65,000 in Yida, Pariang, in addition to 15,000 in Lasu ( CES) and Makpandu (WES). These are living in extremely dire conditions characterized by poor water and sanitation resulting in large public healt h risks for both the refugee and host communities. In August 2012, the WHO STAFF TOGETHER WITH STAFF AT A HEALTHY FACILITY IN LAKES STATES CHECKING THE CONSULTING Ministry of Health declared hepatitis E virus outbreak REGISTER FOR MORBIDITY TRENDS in Maban County. With renewed fighting in the bordering states, it is anticipated that there will be an During this week, WHO; increased refugee influx o f 150,000 in the next few month. Currently, Yida has additional new refugees 1. Supported the County health department in compared to the Maban , mainly due to poor access due to the rains. Maban to coordinate the refugee response with emphasis on disease surveillance in the South Sudan, remains a very expensive and challenging country due to the poor infrastructure. -

Crop Planting Assessment Mission to Greater Bahr El Ghazal Republic of South Sudan July 2014

A partnership between the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, Cooperatives & Rural Development (GRSS-MAFCRD) and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Crop Planting Assessment Mission to Greater Bahr el Ghazal Republic of South Sudan July 2014 Report 2 in preparation for the Crop and Food Security Assessment Mission (CFSAM) Team leader: Dr Ian Robinson, AA International Ltd This report has been produced with the financial support of the EU, under the “Agriculture and Food Information System for Decision Support (AFIS)” Project in South Sudan FAO reference: GCP/SSD/003/EC; EU reference: FED/2012/304-645 CONTENTS 1. OVERVIEW 2. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 2.1 Agricultural systems 2.2 Livestock systems 2.3 Livestock population in South Sudan 3. FACTORS AFFECTING PLANTED AREA 2014 3.1 Rainfall 3.2 Access to land and farmer confidence. 3.3 Power sources 3.4 Input supply 3.5 Crop pest s and diseases 3.6 Livestock movement, numbers and performance 3.7 Livestock body condition 4. CONCLUSIONS 4.1 Effect of rainfall 4.2 Effect of access to land and confidence 4.3 Effect of power supply 4.4 Effect of inputs 4.5 Effect of pest and diseases 4.6 Planted area ANNEX 1 PERSONS MET (EXCLUDING FARMERS/ HERDERS) ANNEX 2 OBSERVATIONAL TRANSECTS ANNEX 3 PLANTING SEASON ASSESSMENT CHECKLIST AND SUMMARY SHEET 1 1. OVERVIEW 1.1 Introduction 1.1.1 An MAFCRD/FAO Planting Assessment Mission visited Greater Bahr el Ghazal from 30th May to 23rd June 2014 to assess the overall land preparation and planting situation in accessible counties in the four constituent states of Western Bahr el Ghazal, Northern Bahr el Ghazal, Warrap and Lakes.