Anurans: Waterfalls, Treefrogs, and Mossy Habitats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diet Composition and Overlap in a Montane Frog Community in Vietnam

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 13(1):205–215. Submitted: 5 November 2017; Accepted: 19 March 2018; Published 30 April 2018. DIET COMPOSITION AND OVERLAP IN A MONTANE FROG COMMUNITY IN VIETNAM DUONG THI THUY LE1,4, JODI J. L. ROWLEY2,3, DAO THI ANH TRAN1, THINH NGOC VO1, AND HUY DUC HOANG1 1Faculty of Biology and Biotechnology, University of Science, Vietnam National University-HCMC, 227 Nguyen Van Cu Street, District 5, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam 2Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum,1 William Street, Sydney, New South Wales 2010, Australia 3Centre for Ecosystem Science, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052, Australia 4Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Southeast Asia is home to a highly diverse and endemic amphibian fauna under great threat. A significant obstacle to amphibian conservation prioritization in the region is a lack of basic biological information, including the diets of amphibians. We used stomach flushing to obtain data on diet composition, feeding strategies, dietary niche breadth, and overlap of nine species from a montane forest in Langbian Plateau, southern Vietnam: Feihyla palpebralis (Vietnamese Bubble-nest Frog), Hylarana montivaga (Langbian Plateau Frog), Indosylvirana milleti (Dalat Frog), Kurixalus baliogaster (Belly-spotted Frog), Leptobrachium pullum (Vietnam Spadefoot Toad), Limnonectes poilani (Poilane’s Frog), Megophrys major (Anderson’s Spadefoot Toad), Polypedates cf. leucomystax (Common Tree Frog), and Raorchestes gryllus (Langbian bubble-nest Frog). To assess food selectivity of these species, we sampled available prey in their environment. We classified prey items into 31 taxonomic groups. Blattodea was the dominant prey taxon for K. -

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

Anura: Brachycephalidae) Com Base Em Dados Morfológicos

Pós-graduação em Biologia Animal Laboratório de Anatomia Comparada de Vertebrados Departamento de Ciências Fisiológicas Instituto de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade de Brasília Sistemática filogenética do gênero Brachycephalus Fitzinger, 1826 (Anura: Brachycephalidae) com base em dados morfológicos Tese apresentada ao Programa de pós-graduação em Biologia Animal para a obtenção do título de doutor em Biologia Animal Leandro Ambrósio Campos Orientador: Antonio Sebben Co-orientador: Helio Ricardo da Silva Maio de 2011 Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Ciências Biológicas Programa de Pós-graduação em Biologia Animal TESE DE DOUTORADO LEANDRO AMBRÓSIO CAMPOS Título: “Sistemática filogenética do gêneroBrachycephalus Fitzinger, 1826 (Anura: Brachycephalidae) com base em dados morfológicos.” Comissão Examinadora: Prof. Dr. Antonio Sebben Presidente / Orientador UnB Prof. Dr. José Peres Pombal Jr. Prof. Dr. Lílian Gimenes Giugliano Membro Titular Externo não Vinculado ao Programa Membro Titular Interno Vinculado ao Programa Museu Nacional - UFRJ UnB Prof. Dr. Cristiano de Campos Nogueira Prof. Dr. Rosana Tidon Membro Titular Interno Vinculado ao Programa Membro Titular Interno Vinculado ao Programa UnB UnB Brasília, 30 de maio de 2011 Dedico esse trabalho à minha mãe Corina e aos meus irmãos Flávio, Luciano e Eliane i Agradecimentos Ao Prof. Dr. Antônio Sebben, pela orientação, dedicação, paciência e companheirismo ao longo do trabalho. Ao Prof. Dr. Helio Ricardo da Silva pela orientação, companheirismo e pelo auxílio imprescindível nas expedições de campo. Aos professores Carlos Alberto Schwartz, Elizabeth Ferroni Schwartz, Mácia Renata Mortari e Osmindo Pires Jr. pelos auxílios prestados ao longo do trabalho. Aos técnicos Pedro Ivo Mollina Pelicano, Washington José de Oliveira e Valter Cézar Fernandes Silveira pelo companheirismo e auxílio ao longo do trabalho. -

The Journey of Life of the Tiger-Striped Leaf Frog Callimedusa Tomopterna (Cope, 1868): Notes of Sexual Behaviour, Nesting and Reproduction in the Brazilian Amazon

Herpetology Notes, volume 11: 531-538 (2018) (published online on 25 July 2018) The journey of life of the Tiger-striped Leaf Frog Callimedusa tomopterna (Cope, 1868): Notes of sexual behaviour, nesting and reproduction in the Brazilian Amazon Thainá Najar1,2 and Lucas Ferrante2,3,* The Tiger-striped Leaf Frog Callimedusa tomopterna 2000; Venâncio & Melo-Sampaio, 2010; Downie et al, belongs to the family Phyllomedusidae, which is 2013; Dias et al. 2017). constituted by 63 described species distributed in In 1975, Lescure described the nests and development eight genera, Agalychnis, Callimedusa, Cruziohyla, of tadpoles to C. tomopterna, based only on spawns that Hylomantis, Phasmahyla, Phrynomedusa, he had found around the permanent ponds in the French Phyllomedusa, and Pithecopus (Duellman, 2016; Guiana. However, the author mentions a variation in the Frost, 2017). The reproductive aspects reported for the number of eggs for some spawns and the use of more than species of this family are marked by the uniqueness of one leaf for confection in some nests (Lescure, 1975). egg deposition, placed on green leaves hanging under The nests described by Lescure in 1975 are probably standing water, where the tadpoles will complete their from Phyllomedusa vailantii as reported by Lescure et development (Haddad & Sazima, 1992; Pombal & al. (1995). The number of eggs in the spawns reported Haddad, 1992; Haddad & Prado, 2005). However, by Lescure (1975) diverge from that described by other exist exceptions, some species in the genus Cruziohyla, authors such as Neckel-Oliveira & Wachlevski, (2004) Phasmahylas and Prhynomedusa, besides the species and Lima et al. (2012). In addition, the use of more than of the genus Agalychnis and Pithecopus of clade one leaf for confection in the nest mentioned by Lescure megacephalus that lay their eggs in lotic environments (1975), are characteristic of other species belonging to (Haddad & Prado, 2005; Faivovich et al. -

Fauna of Australia 2A

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 9. FAMILY MICROHYLIDAE Thomas C. Burton 1 9. FAMILY MICROHYLIDAE Pl 1.3. Cophixalus ornatus (Microhylidae): usually found in leaf litter, this tiny frog is endemic to the wet tropics of northern Queensland. [H. Cogger] 2 9. FAMILY MICROHYLIDAE DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The Microhylidae is a family of firmisternal frogs, which have broad sacral diapophyses, one or more transverse folds on the surface of the roof of the mouth, and a unique slip to the abdominal musculature, the m. rectus abdominis pars anteroflecta (Burton 1980). All but one of the Australian microhylids are small (snout to vent length less than 35 mm), and all have procoelous vertebrae, are toothless and smooth-bodied, with transverse grooves on the tips of their variously expanded digits. The terminal phalanges of fingers and toes of all Australian microhylids are T-shaped or Y-shaped (Pl. 1.3) with transverse grooves. The Microhylidae consists of eight subfamilies, of which two, the Asterophryinae and Genyophryninae, occur in the Australopapuan region. Only the Genyophryninae occurs in Australia, represented by Cophixalus (11 species) and Sphenophryne (five species). Two newly discovered species of Cophixalus await description (Tyler 1989a). As both genera are also represented in New Guinea, information available from New Guinean species is included in this chapter to remedy deficiencies in knowledge of the Australian fauna. HISTORY OF DISCOVERY The Australian microhylids generally are small, cryptic and tropical, and so it was not until 100 years after European settlement that the first species, Cophixalus ornatus, was collected, in 1888 (Fry 1912). As the microhylids are much more prominent and diverse in New Guinea than in Australia, Australian specimens have been referred to New Guinean species from the time of the early descriptions by Fry (1915), whilst revisions by Parker (1934) and Loveridge (1935) minimised the extent of endemism in Australia. -

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Lamoreux, J. F., McKnight, M. W., and R. Cabrera Hernandez (2015). Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. xxiv + 320pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1717-3 DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2015.SSC-OP.53.en Cover photographs: Totontepec landscape; new Plectrohyla species, Ixalotriton niger, Concepción Pápalo, Thorius minutissimus, Craugastor pozo (panels, left to right) Back cover photograph: Collecting in Chamula, Chiapas Photo credits: The cover photographs were taken by the authors under grant agreements with the two main project funders: NGS and CEPF. -

For Review Only

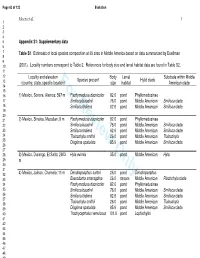

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

The Impact of Anchored Phylogenomics and Taxon Sampling on Phylogenetic Inference in Narrow-Mouthed Frogs (Anura, Microhylidae)

Cladistics Cladistics (2015) 1–28 10.1111/cla.12118 The impact of anchored phylogenomics and taxon sampling on phylogenetic inference in narrow-mouthed frogs (Anura, Microhylidae) Pedro L.V. Pelosoa,b,*, Darrel R. Frosta, Stephen J. Richardsc, Miguel T. Rodriguesd, Stephen Donnellane, Masafumi Matsuif, Cristopher J. Raxworthya, S.D. Bijug, Emily Moriarty Lemmonh, Alan R. Lemmoni and Ward C. Wheelerj aDivision of Vertebrate Zoology (Herpetology), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024, USA; bRichard Gilder Graduate School, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024, USA; cHerpetology Department, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia; dDepartamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociencias,^ Universidade de Sao~ Paulo, Rua do Matao,~ Trav. 14, n 321, Cidade Universitaria, Caixa Postal 11461, CEP 05422-970, Sao~ Paulo, Sao~ Paulo, Brazil; eCentre for Evolutionary Biology and Biodiversity, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; fGraduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan; gSystematics Lab, Department of Environmental Studies, University of Delhi, Delhi 110 007, India; hDepartment of Biological Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306, USA; iDepartment of Scientific Computing, Florida State University, Dirac Science Library, Tallahassee, FL 32306-4120, USA; jDivision of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024, USA Accepted 4 February 2015 Abstract Despite considerable progress in unravelling the phylogenetic relationships of microhylid frogs, relationships among subfami- lies remain largely unstable and many genera are not demonstrably monophyletic. -

Polyploidy and Sex Chromosome Evolution in Amphibians

Chapter 18 Polyploidization and Sex Chromosome Evolution in Amphibians Ben J. Evans, R. Alexander Pyron and John J. Wiens Abstract Genome duplication, including polyploid speciation and spontaneous polyploidy in diploid species, occurs more frequently in amphibians than mammals. One possible explanation is that some amphibians, unlike almost all mammals, have young sex chromosomes that carry a similar suite of genes (apart from the genetic trigger for sex determination). These species potentially can experience genome duplication without disrupting dosage stoichiometry between interacting proteins encoded by genes on the sex chromosomes and autosomalPROOF chromosomes. To explore this possibility, we performed a permutation aimed at testing whether amphibian species that experienced polyploid speciation or spontaneous polyploidy have younger sex chromosomes than other amphibians. While the most conservative permutation was not significant, the frog genera Xenopus and Leiopelma provide anecdotal support for a negative correlation between the age of sex chromosomes and a species’ propensity to undergo genome duplication. This study also points to more frequent turnover of sex chromosomes than previously proposed, and suggests a lack of statistical support for male versus female heterogamy in the most recent common ancestors of frogs, salamanders, and amphibians in general. Future advances in genomics undoubtedly will further illuminate the relationship between amphibian sex chromosome degeneration and genome duplication. B. J. Evans (CORRECTED&) Department of Biology, McMaster University, Life Sciences Building Room 328, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, ON L8S 4K1, Canada e-mail: [email protected] R. Alexander Pyron Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, 2023 G St. NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA J. -

Summary Conservation Action Plans for Mongolian Reptiles and Amphibians

Summary Conservation Action Plans for Mongolian Reptiles and Amphibians Compiled by Terbish, Kh., Munkhbayar, Kh., Clark, E.L., Munkhbat, J. and Monks, E.M. Edited by Munkhbaatar, M., Baillie, J.E.M., Borkin, L., Batsaikhan, N., Samiya, R. and Semenov, D.V. ERSITY O IV F N E U D U E T C A A T T S I O E N H T M ONGOLIA THE WORLD BANK i ii This publication has been funded by the World Bank’s Netherlands-Mongolia Trust Fund for Environmental Reform. The fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colours, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgement on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The World Conservation Union (IUCN) have contributed to the production of the Summary Conservation Action Plans for Mongolian Reptiles and Amphibians, providing technical support, staff time, and data. IUCN supports the production of the Summary Conservation Action Plans for Mongolian Reptiles and Amphibians, but the information contained in this document does not necessarily represent the views of IUCN. Published by: Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY Copyright: © Zoological Society of London and contributors 2006. -

View Preprint

A peer-reviewed version of this preprint was published in PeerJ on 30 March 2017. View the peer-reviewed version (peerj.com/articles/3077), which is the preferred citable publication unless you specifically need to cite this preprint. Oliver PM, Iannella A, Richards SJ, Lee MSY. 2017. Mountain colonisation, miniaturisation and ecological evolution in a radiation of direct-developing New Guinea Frogs (Choerophryne, Microhylidae) PeerJ 5:e3077 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3077 Mountain colonisation, miniaturisation and ecological evolution in a radiation of direct developing New Guinea Frogs (Choerophryne, Microhylidae) Paul M Oliver Corresp., 1 , Amy Iannella 2 , Stephen J Richards 3 , Michael S.Y Lee 3, 4 1 Division of Ecology and Evolution, Research School of Biology & Centre for Biodiversity Analysis, Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia 2 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia 3 South Australian Museum, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia 4 School of Biological Sciences, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia Corresponding Author: Paul M Oliver Email address: [email protected] Aims. Mountain ranges in the tropics are characterised by high levels of localised endemism, often-aberrant evolutionary trajectories, and some of the world’s most diverse regional biotas. Here we investigate the evolution of montane endemism, ecology and body size in a clade of direct-developing frogs (Choerophryne, Microhylidae) from New Guinea. Methods. Phylogenetic relationships were estimated from a mitochondrial molecular dataset using Bayesian and maximum likelihood approaches. Ancestral state reconstruction was used to infer the evolution of elevational distribution, ecology (indexed by male calling height), and body size, and phylogenetically corrected regression was employed to examine the relationships between these three traits. -

The Most Frog-Diverse Place in Middle America, with Notes on The

Offcial journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(2) [Special Section]: 304–322 (e215). The most frog-diverse place in Middle America, with notes on the conservation status of eight threatened species of amphibians 1,2,*José Andrés Salazar-Zúñiga, 1,2,3Wagner Chaves-Acuña, 2Gerardo Chaves, 1Alejandro Acuña, 1,2Juan Ignacio Abarca-Odio, 1,4Javier Lobon-Rovira, 1,2Edwin Gómez-Méndez, 1,2Ana Cecilia Gutiérrez-Vannucchi, and 2Federico Bolaños 1Veragua Foundation for Rainforest Research, Limón, COSTA RICA 2Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, 11501-2060 San José, COSTA RICA 3División Herpetología, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘‘Bernardino Rivadavia’’-CONICET, C1405DJR, Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA 4CIBIO Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources, InBIO, Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrário de Vairão, Rua Padre Armando Quintas 7, 4485-661 Vairão, Vila do Conde, PORTUGAL Abstract.—Regarding amphibians, Costa Rica exhibits the greatest species richness per unit area in Middle America, with a total of 215 species reported to date. However, this number is likely an underestimate due to the presence of many unexplored areas that are diffcult to access. Between 2012 and 2017, a monitoring survey of amphibians was conducted in the Central Caribbean of Costa Rica, on the northern edge of the Matama mountains in the Talamanca mountain range, to study the distribution patterns and natural history of species across this region, particularly those considered as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The results show the highest amphibian species richness among Middle America lowland evergreen forests, with a notable anuran representation of 64 species.