Historical Review20i7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Identifier

Field Field Description Field Field Nr. Abbrev'n Length 1 Record type indicator RECID 5 2 HESA institution identifier INSTID 4 3 Campus identifier CAMPID 1 4 Student identifier HUSID 13 5 Scottish candidate number SCOTVEC 9 6 FE student marker FESTUMK 1 7 Family name SURNAME 40 8 Forenames FNAMES 40 9 Family name on 16th birthday SNAME16 40 10 Date of birth BIRTHDTE 10 11 Gender GENDER 1 12 Domicile DOMICILE 4 13 Nationality NATION 4 14 Ethnicity ETHNIC 2 15 Disability allowance DISALL 1 16 Disability DISABLE 2 17 Additional support band ADSPBAND 2 18 Not used LASTINST 7 19 Year left last institution YRLLINST 4 20 Not used QUALENT1 2 21 Highest qualification on entry QUALENT2 2 22 Not used QSTAT 1 23 Not used. ALEVPTS 2 24 Not used. HIGHPTS 2 25 Occupation code OCCCODE 4 26 Date of commencement of programme COMDATE 10 27 New entrant to HE ENTRYCDE 1 28 Special students SPCSTU 1 29 Teacher reference number TREFNO 9 30 Year of student on this programme YEARSTU 2 31 Term time accommodation TTACCOM 1 32 Not used FINYM 1 33 Reason for leaving institution/completing programme RSNLEAVE 2 34 Completion status CSTAT 1 35 Date left institution or completed the programme of study DATELEFT 10 36 Good standing marker PROGRESS 1 37 Qualification obtained 1 QUAL1 2 38 Qualification obtained 2 QUAL2 2 39 Classification CLASS 2 40 Programme of study title PTITLE 80 41 General qualification aim of student QUALAIM 2 42 FE general qualification aim of student FEQAIM 8 43 Subject(s) of qualification aim SBJQA1 6 44 Subject of qualification aim 2 SBJQA2 4 -

BRASILIANA 5.ª Sl!:RIE DA BIBLIOTECA PEDA Gôgica BRASILEIRA SOB a DIREÇÃO DE FERNIANDO DE AZEVEDO VOLUMES PUBLICADOS

BRASILIANA 5.ª Sl!:RIE DA BIBLIOTECA PEDA GôGICA BRASILEIRA SOB A DIREÇÃO DE FERNIANDO DE AZEVEDO VOLUMES PUBLICADOS ANTROPOLOGIA E DEMOGRAFIA 81 - Lemos Brito: A Gloriosa Sotal rta do Primeiro Império - Frei 4 - Ollvelra Viana: Raça e Assimi Caneca - Edição 11ustr9:da. lação - 3.• edição (aumentada). as· - Wanderley Pinho: Cotegipe e 8 - Oliveira Viana: Populações Me seu Tempo - Ed. Ilustrada. r_idl_onaJs do 13rasll - 4.ª edição. 88 - Hélio Lobo: Um Varão da Re 9 - Nina Rodrigues: Os Africanos pública: Fernando Lobo. no Brasil - (Revisão e prefácio de Homero Pires). Profusamente Ilus 114 - Carlos Süsseklnd de Mendonça: trado - 2.ª edição. Sllvio Romero - sua Fotmaçe.o Intellectual - 1851-1880 - Com 22 -E. Roquette-Plnto: Ensaios de uma Introdução bibliográfica Antropologia Brasileira. Ed. Ilustrada. 2'7 - Alfredo Ellls Júnior; Popula ções Paullstas. 119 - Sud Mennuccl: O Precursor do Abolicionismo - Luiz Gama 59 - Alfredo Ellls Júnior: Os Pri Ed. Ilustrada. meiros Troncos Paullstas e o cru- 2amento Euro-Americano. 120 - Pedro Calmon: O Rei Filósofo - Vida de D. Pedro II - 2.ª ARQUEOLOGIA E PREHIS'J:0RIA Edição Ilustrada. , 133 - Heitor Lira: História de Dom 34 - Anglone costa: Introdução ã Pedro II - 1825-1891 - Vol. 1.0; Arqueologia Brasileira - Ed. uus- , "Ascenção" - 1825-1870 - Ed. !1. trada. 133-A - Heitor Lira: História de Dllln 137 - Antbal Matos: Prehlstórla Bra Pedro II - 1825-1891 - 2.0 Vo sileira - Vârlos Estudos - Ed. li. lume: "Fastlglo": 1870•1880 - Ed. 148 - Anlbal Matos: Peter Wilhem Ilustrada. Lund no Brasil - Problemas de Paleontologia Brasileira. Ed. Ilus 135 - Alberto Ptzarro Jacobina: Dias trada. Carneiro (O Conservador) - Ed. Ilustrada. -

Block 6 and Beyond

ANNUAL PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT DATASET Southend-on-Sea Produced November 2007 Page 1 of 274 APA dataset guidance notes Revisions in the APA 2007 dataset. The following revisions have been made to data presented in the first (August) version of the dataset. 1002HC In the data definition section, the sub-heading read ‘Commentary on Bristol values:’ for all local authorities, so has been revised to ‘Commentary:’. The data and traffic lights were referring to the correct local authorities so are unchanged. 1044HC The second part of this indicator relates to 'Under 18s on adult wards that are 16 or 17'. This text was missing from the description for some local authorities but has now been added. 1043SC The bandings for some councils were previously increased by one band colour. They are now accurately coloured for all councils. The data is unchanged. 2022SC The bandings for all councils have now been uprated for 2006-07. The data is unchanged. 2037SC The denominator data has been revised to use section 47 data rather than conference data. The data may be revised downwards as a result. 2054SC The denominator data has been revised to exclude all the children listed in the definition. The data may be revised upwards very slightly as a result. 2066SC The denominator data has been revised to omit the unborn. The data may be revised upwards very slightly as a result. 3035OF The statistical neighbours traffic lights for authorised and unauthorised absences were incorrectly based on the ‘old’ Ofsted statistical neighbours. They are now correctly based on the ‘new’ NFER statistical neighbours. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

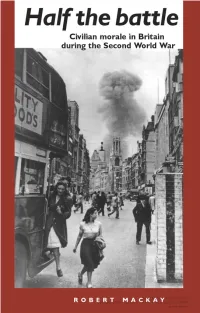

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM Via Free Access HALF the BATTLE

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access HALF THE BATTLE Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 1 16/09/02, 09:21 Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 2 16/09/02, 09:21 HALF THE BATTLE Civilian morale in Britain during the Second World War ROBERT MACKAY Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 3 16/09/02, 09:21 Copyright © Robert Mackay 2002 The right of Robert Mackay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 5893 7 hardback 0 7190 5894 5 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs. -

Telephone Directory

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Organizational Directory 1/19/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Organizational Directory United States Department of State 2201 C Street NW, Washington, DC 20520 Office of the Secretary (S) Emergency and Evacuations Planning CMS Staff 202-647-7640 7516 Secretary Emergency Relocation CMS Staff 7516 202-647-7640 Secretary Michael R Pompeo 7th Floor 202-647-4000 Resident task force ONLY Task Force 1 7516 202-647-6611 Executive Assistant Timmy T Davis 7226 202-647-4000 Consular task force ONLY Task Force 2 (CA) 7516 202-647-7004 Special Assistant Andrew Lederman 7226 202-647-4000 Resident task force ONLY Task Force 3 7516 202-647-6613 Special Assistant Kathryn L Donnell 7226 202-647-4000 Special Assistant Jeffrey H Sillin 7226 202-647-4000 Office of the Executive Director (S/ES-EX) Special Assistant Victoria Ellington 7226 202-647-4000 Executive Director, Deputy Executive Secretary 202-647-7457 Scheduling & Advance Joseph G Semrad 7226 202-647-4000 Howard VanVranken 7507 Scheduler Ruth Fisher 7226 202-647-4000 Deputy Executive Director Michelle Ward 7507 202-647-5475 Office Manager Sally Ritchie 7226 202-647-4000 Budget Officer Reginald J. Green 7515 202-647-9794 Office Manager Hillaire Campbell 7226 202-647-4000 Bureau Security Officer Dave Shamber 5634 202-647-7478 Senior Advisor Mary Kissel 7242 202-647-4000 Human Resources Division Director Eboni C 202-647-5478 Staff Asst. to SA Kissel Simonette -

Some Characteristics of Ethnic Identity

Rajović G. – Some Characteristics of Ethnic Identity Cultural Anthropology Some Characteristics of Ethnic Identity Case Study: Migrants from Serbia and Montenegro to Denmark Goran Rajović1 Abstract. The following text is a contribution to the study of migration, in order to be closer to the main problems of contemporary migration flows from Serbia and Montenegro to Denmark, through the presentation of various data and results obtained in the current studies of the phenomenon of migration. Attention is paid to economic migration, with an emphasis on the characteristics of ethnic identity perceived from the point of view: family ritual practices associated with religious holidays, life cycle of an individual (birth, marriage, death), use of traditional foods, drinks, music and games in festive occasions, possession and use of objects from their homeland (inherited and acquired) with regard to the identity of the elements of traditional attitudes and practices of the respondents. Since the notion of ethnic identity complex, it is necessary to considered in the more theoretical approach or framework. Therefore, there are two interpretations: one given by the respondents, and other researchers. Serbian and Montenegrin communities of migrants, although not many (about 8,000), is interesting for researchers, because in the middle of Denmark that is economically dependent, maintained their ethnic or social identity. Key words: Migrants, Serbia and Montenegro, Denmark, ethnic identity. Introduction Serbia and Montenegro have traditionally emigration areas. According Baščarević (2011), the first major wave of emigration occurred in the early twentieth century, has continued especially after the Second World War, and primarily motivated by political and economic reasons. -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films. -

An Introductory History of British Broadcasting

An Introductory History of British Broadcasting ‘. a timely and provocative combination of historical narrative and social analysis. Crisell’s book provides an important historical and analytical introduc- tion to a subject which has long needed an overview of this kind.’ Sian Nicholas, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television ‘Absolutely excellent for an overview of British broadcasting history: detailed, systematic and written in an engaging style.’ Stephen Gordon, Sandwell College An Introductory History of British Broadcasting is a concise and accessible history of British radio and television. It begins with the birth of radio at the beginning of the twentieth century and discusses key moments in media history, from the first wireless broadcast in 1920 through to recent developments in digital broadcasting and the internet. Distinguishing broadcasting from other kinds of mass media, and evaluating the way in which audiences have experienced the medium, Andrew Crisell considers the nature and evolution of broadcasting, the growth of broadcasting institutions and the relation of broadcasting to a wider political and social context. This fully updated and expanded second edition includes: ■ The latest developments in digital broadcasting and the internet ■ Broadcasting in a multimedia era and its prospects for the future ■ The concept of public service broadcasting and its changing role in an era of interactivity, multiple channels and pay per view ■ An evaluation of recent political pressures on the BBC and ITV duopoly ■ A timeline of key broadcasting events and annotated advice on further reading Andrew Crisell is Professor of Broadcasting Studies at the University of Sunderland. He is the author of Understanding Radio, also published by Routledge. -

Five Issues of the Social S4ence Teacher Are Presented for 1976

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 142 496 SO 010 201 TITLE The Social Science Teacher, Vol. 5, No. 2, Feb. 1976, Vol. 5, No. 3, April 1976, Vol. 5, No.4, June 1976, Vol. 6, No.1, October 1976 [And] Vol. 6, No. 2, November 1976. INSTITUTION Association for the Teaching of the Social Sciences (England). puB DATE 76 NOTE 241p.; For related documents, see ED 098 083, ED 098 117, ED 102 069, and SO 010 200-202; Not available in hard copy due to small type size of original documents EDRS PRIcE MF-$0.83 Plus Postage. BC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Comparative Education; Curriculum; Demonstration Programs; *Educational Trends; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Gaules;- Learning Activities; *Periodicals; Program Evaluation; Social Change; *Social Sciences; *Social Studies; Sociology; *Teaching Methods; Textbooks; Values IDENTIFIERS England ABSTRACT All five issues of The Social S4ence Teacher are presented for 1976. They contain articles and resources for social science teaching on elementary and secondary levels in England. The February issue examines assessment of social science programs, the ideological potential of high sehool sociology, and an experimental program of ',linkage,' whereby students in twoschools teach each other by exchanging learning packages, Articles in the April issue focus on social change and social control as goals of studying society, usefulness of traditional standard examinations for new social science curricula, and an experimental sociology program which studies community rights. The June and October issues are special editions on school textbooks and curriculum projects, and games and simulations, respectively. The November issue includes articles on cultural studies and values education, and on teaching the conceptof role. -

Martina Baleva the Heroic Lens: Portrait Photography of Ottoman

MARtiNA BALEVA THE HEROic LENS: PORTRAit PHOTOGRAPHY OF OttOMAN INSURGENTS IN THE NiNETEENTH-CENTURY BAlkANS—TYPES AND USES “In front of the lens, I am at the same time: the one I think I am, the one I want others to think I am.” (Roland Barthes) In his essay on the constitutive role of photography in the construction of collective identities in nineteenth-century Romania, the photohistorian Adrian-Silvan Ionescu identifies a genre of photographic portraits as representations of “Bulgarian national heroes.”1 Unfortunately, Ionescu leaves open the question of what exactly he means by this term, and he does not give a visual example of this photographic genre. Indeed, a large number of portrait photographs of Ottoman Bulgarians posed in a “heroic” manner exist, all made in the second half of the nineteenth century in Romanian photography studios. Many of them are today an integral part of the Bul- garian historical tradition, and they have become deeply imprinted onto the visual memories of generations as a testimony to and documentation of the Bulgarian national movement against Ottoman rule (c. 1396–1878). Not a single history book has failed to reproduce them, and they hang in every school and public building. Even the uniforms of the National Guard today are influenced by this photographic genre, which Ionescu would later accurately sum up as the “Bulgarian national hero.” It is obvious that Ionescu did not derive the term from this particular “heroic” pictorial tradition but from another kind of photographic genre: “Oriental-type” photography. More exactly, Ionescu has very likely borrowed it from the title of a photograph taken by the famous Viennese photographer Ludwig Angerer (1827–1879) during the Crimean War (1853–1856), probably in Bucharest (fig. -

Esportes 20Caderno

Ano CXX1 Número 194 R$ 1,00 Assinatura anual R$ 160,00 JoãoA Pessoa, Paraíba - QUARTA-FEIRA,UNIÃO 17 de setembro de 2014 121 A nos - PATRIMÔnIo DA PARAÍBA www.paraiba.pb.gov.br auniao.pb.gov.br facebook.com/uniaogovpb Twitter > @uniaogovpb CONCURSO NO S ÁBADO PágInA 15 ELEIÇÕES 20Caderno Bombeiros e Emepa faz leilão de gado Votação PM vão fazer no município de Umbuzeiro paralela vai psicotécnico ser no dia 5 FOTO: Divulgação Segunda fase A Justiça Eleito- do concurso vai acontecer domingo. PÁGInA 13 urnas.ral quer PÁG confirmarInA 17 a confiabilidade das LEGISLAÇÃO CORRUPÇÃO Lei Maria da CPMI pode Penha é tema ter reunião Célia Araújo integra o grupo de diálogos fechada MODA PágInA 5 Entidades de de- Depoimento de fesa dos direitos da FOTO: Arquivo ex-diretor da Petro- Paraibanos vão mulher participam bras vai acontecer participar de de mesa de diálogo hoje. PÁGInA 18 amanhã. PÁGInA 9 feira em Paris serviços da PB têm 4ª maior alta do país O IBGE divulgou ontem que o setor de serviços da Paraíba registrou a quarta maior alta do país e a maior do Nordeste entre os meses de janeiro e julho deste ano. O setor apresentou expansão de 10,2% em comparação ao mesmo período de 2013. No acumulado dos 12 meses, o crescimento foi de 10,9%. O setor de serviços tem o maior peso bruto no PIB. PágInA 14 FOTO: Edson Matos Estados se posicionam contra revistas íntimas A Paraíba está entre os Estados brasileiros que discordam da revis- ta íntima em presídios. PÁGInA 10 Extração de areia em rios tem nova regra aprovada O documento terá validade para todo o território paraibano e evitará degradação ambiental.