Bsafe Pilot Project 2007-2010 Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anonymity in a Time of Surveillance

LESSONS LEARNED TOO WELL: ANONYMITY IN A TIME OF SURVEILLANCE A. Michael Froomkin* It is no longer reasonable to assume that electronic communications can be kept private from governments or private-sector actors. In theory, encryption can protect the content of such communications, and anonymity can protect the communicator’s identity. But online anonymity—one of the two most important tools that protect online communicative freedom—is under practical and legal attack all over the world. Choke-point regulation, online identification requirements, and data-retention regulations combine to make anonymity very difficult as a practical matter and, in many countries, illegal. Moreover, key internet intermediaries further stifle anonymity by requiring users to disclose their real names. This Article traces the global development of technologies and regulations hostile to online anonymity, beginning with the early days of the Internet. Offering normative and pragmatic arguments for why communicative anonymity is important, this Article argues that anonymity is the bedrock of online freedom, and it must be preserved. U.S. anti-anonymity policies not only enable repressive policies abroad but also place at risk the safety of anonymous communications that Americans may someday need. This Article, in addition to providing suggestions on how to save electronic anonymity, calls for proponents of anti- anonymity policies to provide stronger justifications for such policies and to consider alternatives less likely to destroy individual liberties. In -

RSA BSAFE Crypto-C 5.21 FIPS 140-1 Security Policy2.…

RSA Security, Inc. RSA™ BSAFE® Crypto-C Crypto-C Version 5.2.1 FIPS 140-1 Non-Proprietary Security Policy Level 1 Validation Revision 1.0, May 2001 © Copyright 2001 RSA Security, Inc. This document may be freely reproduced and distributed whole and intact including this Copyright Notice. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 PURPOSE ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 DOCUMENT ORGANIZATION ............................................................................................... 3 2 THE RSA BSAFE PRODUCTS............................................................................................ 5 2.1 THE RSA BSAFE CRYPTO-C TOOLKIT MODULE .............................................................. 5 2.2 MODULE INTERFACES ......................................................................................................... 5 2.3 ROLES AND SERVICES ......................................................................................................... 6 2.4 CRYPTOGRAPHIC KEY MANAGEMENT ................................................................................ 7 2.4.1 Protocol Support........................................................................................................ -

![Arxiv:1911.09312V2 [Cs.CR] 12 Dec 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5245/arxiv-1911-09312v2-cs-cr-12-dec-2019-485245.webp)

Arxiv:1911.09312V2 [Cs.CR] 12 Dec 2019

Revisiting and Evaluating Software Side-channel Vulnerabilities and Countermeasures in Cryptographic Applications Tianwei Zhang Jun Jiang Yinqian Zhang Nanyang Technological University Two Sigma Investments, LP The Ohio State University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—We systematize software side-channel attacks with three questions: (1) What are the common and distinct a focus on vulnerabilities and countermeasures in the cryp- features of various vulnerabilities? (2) What are common tographic implementations. Particularly, we survey past re- mitigation strategies? (3) What is the status quo of cryp- search literature to categorize vulnerable implementations, tographic applications regarding side-channel vulnerabili- and identify common strategies to eliminate them. We then ties? Past work only surveyed attack techniques and media evaluate popular libraries and applications, quantitatively [20–31], without offering unified summaries for software measuring and comparing the vulnerability severity, re- vulnerabilities and countermeasures that are more useful. sponse time and coverage. Based on these characterizations This paper provides a comprehensive characterization and evaluations, we offer some insights for side-channel of side-channel vulnerabilities and countermeasures, as researchers, cryptographic software developers and users. well as evaluations of cryptographic applications related We hope our study can inspire the side-channel research to side-channel attacks. We present this study in three di- community to discover new vulnerabilities, and more im- rections. (1) Systematization of literature: we characterize portantly, to fortify applications against them. the vulnerabilities from past work with regard to the im- plementations; for each vulnerability, we describe the root cause and the technique required to launch a successful 1. -

Black-Box Security Analysis of State Machine Implementations Joeri De Ruiter

Black-box security analysis of state machine implementations Joeri de Ruiter 18-03-2019 Agenda 1. Why are state machines interesting? 2. How do we know that the state machine is implemented correctly? 3. What can go wrong if the implementation is incorrect? What are state machines? • Almost every protocol includes some kind of state • State machine is a model of the different states and the transitions between them • When receiving a messages, given the current state: • Decide what action to perform • Which message to respond with • Which state to go the next Why are state machines interesting? • State machines play a very important role in security protocols • For example: • Is the user authenticated? • Did we agree on keys? And if so, which keys? • Are we encrypting our traffic? • Every implementation of a protocol has to include the corresponding state machine • Mistakes can lead to serious security issues! State machine example Confirm transaction Verify PIN 0000 Failed Init Failed Verify PIN 1234 OK Verified Confirm transaction OK State machines in specifications • Often specifications do not explicitly contain a state machine • Mainly explained in lots of prose • Focus usually on happy flow • What to do if protocol flow deviates from this? Client Server ClientHello --------> ServerHello Certificate* ServerKeyExchange* CertificateRequest* <-------- ServerHelloDone Certificate* ClientKeyExchange CertificateVerify* [ChangeCipherSpec] Finished --------> [ChangeCipherSpec] <-------- Finished Application Data <-------> Application Data -

1 Term of Reference Reference Number TOR-VNM-2021-21

Term of Reference Reference number TOR-VNM-2021-21 (Please refer to this number in the application) Assignment title International Gender Consultant Purpose to develop a technical paper comparing legal frameworks and setting out good practices for legal recognition of gender identity/protection of the human rights of trans persons in other countries/regions. Location Home-based Contract duration 1 June 2021 – 31 August 2021 (32 working days) Contract supervision UN Women Programme Specialist UN Women Viet Nam Country Office I. Background UN Women Grounded in the vision of equality enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations, the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women) works for the elimination of discrimination against women and girls; the empowerment of women; and the achievement of substantive equality between women and men. The fundamental objective of UN Women is to enhance national capacity and ownership to enable national partners to formulate gender responsive laws, policies and upscale successful strategies to deliver on national and international commitments to gender equality. UN Women Viet Nam Country Office is the chair of the UN Gender Theme Group and has been an active member of the UN Human Rights Thematic Group (HRTG) and Viet Nam UN HIV Thematic Group and acts as a leading agency in related to promoting gender equality in the national HIV response. The result under this LOA will contribute to the achievements of the following outcome and output of UN Women Viet Nam’s Annual Work Plan. - VCO Impact 3 (SP outcome 4): Women and girls live a life free from violence. -

Policy and Procedures for Contracting Individual Consultants

UNFPA Policies and Procedures Manual: Human Resources: Policy and Procedures for Contracting Individual Consultants Policy Title Policy and Procedures for Contracting Individual Consultants Previous title (if any) Individual Consultants Policy objective The purpose of this policy is to set out how Hiring Offices can contract the temporary services of individuals as consultants. Target audience Hiring Offices Risk control matrix Control activities that are part of the process are detailed in the Risk Control Matrix Checklist N/A Effective date 1 June 2019 Revision History Issued: 1 September 2015 Rev 1: August 2017 Mandatory revision 1 June 2022 date Policy owner unit Division for Human Resources Approval Signed approval UNFPA Policies and Procedures Manual: Human Resources: Policy and Procedures for Contracting Individual Consultants POLICY AND PROCEDURES FOR CONTRACTING INDIVIDUAL CONSULTANTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PURPOSE ....................................................................................................................... 1 II. POLICY ........................................................................................................................... 1 III. PROCEDURES ............................................................................................................... 2 Initiating request for individual consultant ............................................................................ 2 Verifying availability of funds .............................................................................................. -

Chapter 11: Building Secure Software Lars-Helge Netland [email protected] 10.10.2005 INF329: Utvikling Av Sikre Applikasjoner Overview

Programming with cryptography Chapter 11: Building Secure Software Lars-Helge Netland [email protected] 10.10.2005 INF329: Utvikling av sikre applikasjoner Overview Intro: The importance of cryptography The fundamental theorem of cryptography Available cryptographic libraries Java code examples One-time pads Summary 2 Intro Cryptography ‘kryptos’(=hidden) ‘graphein’ (=to write) Layman description: the science of encrypting and decrypting text 3 The Code Book Simon Singh Highly accessible introduction to cryptography Retails at $10 (free at public libraries) Includes crypto challenges 4 Crypto: Why is it important?(I) Basic services: confidentiality encrypted text only viewable by the intended recipient integrity assurance to the involved parties that the text was not tampered with in transit authentication proof of a binding of an identity to an identification tag (often involves trusted third parties) 5 Crypto: Why is it important?(II) Basic services (continued) authorization restricting access to resources (often involves authentication) digital signatures electronic equivalent of hand-written signatures non-repudiation 6 The fundamental theorem of cryptography Do NOT develop your own cryptographic primitives or protocols The history of cryptography repeatedly shows how “secure” systems have been broken due to unknown vulnerabilities in the design If you really have to: PUBLISH the algorithm 7 Examples on how ciphers have been broken Early substitution ciphers broken by exploiting the relative frequency of letters WW2: The enigma machine -

RSA BSAFE Crypto-C Micro Edition 4.1.4 Security Policy Level 1

Security Policy 28.01.21 RSA BSAFE® Crypto-C Micro Edition 4.1.4 Security Policy Level 1 This document is a non-proprietary Security Policy for the RSA BSAFE Crypto-C Micro Edition 4.1.4 (Crypto-C ME) cryptographic module from RSA Security LLC (RSA), a Dell Technologies company. This document may be freely reproduced and distributed whole and intact including the Copyright Notice. Contents: Preface ..............................................................................................................2 References ...............................................................................................2 Document Organization .........................................................................2 Terminology .............................................................................................2 1 Crypto-C ME Cryptographic Toolkit ...........................................................3 1.1 Cryptographic Module .......................................................................4 1.2 Crypto-C ME Interfaces ..................................................................17 1.3 Roles, Services and Authentication ..............................................19 1.4 Cryptographic Key Management ...................................................20 1.5 Cryptographic Algorithms ...............................................................24 1.6 Self Tests ..........................................................................................30 2 Secure Operation of Crypto-C ME ..........................................................33 -

Conference Reports

ConferenceREPORTS Reports 23rd USENIX Security Symposium AT&T was a US government regulated monopoly, with over August 20–22, 2014, San Diego 90% of the telephone market in the US. They owned everything, Summarized by David Adrian, Qi Alfred Chen, Andrei Costin, Lucas Davi, including the phones on desktops and in homes, and, as a monop- Kevin P. Dyer, Rik Farrow, Grant Ho, Shouling Ji, Alexandros Kapravelos, oly, could and did charge as much as $5 per minute (in 1950) for a Zhigong Li, Brendan Saltaformaggio, Ben Stock, Janos Szurdi, Johanna cross-country call. In 2014 dollars, that’s nearly $50 per minute. Ullrich, Venkatanathan Varadarajan, and Michael Zohner In the beginning, the system relied on women, sitting in front Opening Remarks of switchboards with patch cables in hand, to connect calls. Summarized by Rik Farrow ([email protected]) Just like Google today, AT&T realized that this model, relying on human labor, cannot scale with the growth in the use of the Kevin Fu, chair of the symposium, started off with the numbers: telephone: They would have needed one million operators by a 26% increase in the number of submissions for a total of 350, 1970. Faced with this issue, company researchers and engineers and 67 papers accepted, a rate of 19%. The large PC was perhaps developed electro-mechanical switches to replace operators. not large enough, even with over 70 members, and included out- side reviewers as well. There were 1340 paper reviews, with 1627 The crossbar switch, first used only for local calls, used the pulse follow-up comments, and Fu had over 8,269 emails involving the of the old rotary telephone to manipulate a Strowger switch, symposium. -

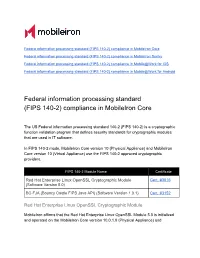

Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS 140-2) Compliance in Mobileiron Core

Federal information processing standard (FIPS 140-2) compliance in MobileIron Core Federal information processing standard (FIPS 140-2) compliance in MobileIron Sentry Federal information processing standard (FIPS 140-2) compliance in Mobile@Work for iOS Federal information processing standard (FIPS 140-2) compliance in Mobile@Work for Android Federal information processing standard (FIPS 140-2) compliance in MobileIron Core The US Federal information processing standard 140-2 (FIPS 140-2) is a cryptographic function validation program that defines security standards for cryptographic modules that are used in IT software. In FIPS 140-2 mode, MobileIron Core version 10 (Physical Appliance) and MobileIron Core version 10 (Virtual Appliance) use the FIPS 140-2 approved cryptographic providers: FIPS 140-2 Module Name Certificate Red Hat Enterprise Linux OpenSSL Cryptographic Module Cert. #3016 (Software Version 5.0) BC-FJA (Bouncy Castle FIPS Java API) (Software Version 1.0.1) Cert. #3152 Red Hat Enterprise Linux OpenSSL Cryptographic Module MobileIron affirms that the Red Hat Enterprise Linux OpenSSL Module 5.0 is initialized and operated on the MobileIron Core version 10.0.1.0 (Physical Appliance) and MobileIron Core version 10.0.1.0 (Virtual Appliance), using the associated FIPS 140-2 security policy as a reference. https://csrc.nist.gov/Projects/Cryptographic-Module-Validation-Program/Certificate/3016 BC-FJA (Bouncy Castle FIPS Java API) Module MobileIron affirms that BC-FJA (Bouncy Castle FIPS Java API) is initialized and operated on the MobileIron Core version 10.0.1.0 (Physical Appliance) and MobileIron Core version 10.0.1.0 (Virtual Appliance), using the associated FIPS 140-2 security policy as a reference. -

Genesys Security Deployment Guide

Genesys Security Deployment Guide TLS Implementations in Genesys 10/1/2021 Contents • 1 TLS Implementations in Genesys • 1.1 Summary • 1.2 Genesys Native Applications on Windows • 1.3 Genesys Native Applications – Genesys Security Pack on UNIX • 1.4 Java PSDK Implementation • 1.5 .NET PSDK Implementation Genesys Security Deployment Guide 2 TLS Implementations in Genesys TLS Implementations in Genesys TLS is a protocol with an agreed-upon standard definition. To utilize TLS in real applications, the protocol must be implemented in source code. Many different TLS implementations exist, some developing and patching newly found security issues, and some of them not. Refer to Comparison of TLS implementations to see what TLS implementations exist and how they differ. All TLS implementations differ in the list of supported features, aspects, protocol versions and cipher lists. However, all TLS implementations still implement the same TLS, and therefore should be able to communicate with each other, given that a compatible set of features is requested at each end of the connection. Even Genesys implementations vary. For example: • Genesys uses different technologies (C++, Java, and so on) • Genesys operates on different infrastructures (Windows, Unix) Summary Genesys products use the following TLS implementations for their proprietary protocols, depending on the component platform. TLS Implementation Environment Platform Keystore Used Genesys native Microsoft SChannel (built Windows Certificate Microsoft Windows applications (with no into the -

Download CVS 1.11.1P1-3 From: Ftp://Ftp.Software.Ibm.Com/Aix/Freesoftware/Aixtoolbox/RPMS/Ppc/Cvs/ Cvs-1.11.1P1-3.Aix4.3.Ppc.Rpm

2003 CERT Advisories CERT Division [DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A] Approved for public release and unlimited distribution. http://www.sei.cmu.edu REV-03.18.2016.0 Copyright 2017 Carnegie Mellon University. All Rights Reserved. This material is based upon work funded and supported by the Department of Defense under Contract No. FA8702-15-D-0002 with Carnegie Mellon University for the operation of the Software Engineering Institute, a federally funded research and development center. The view, opinions, and/or findings contained in this material are those of the author(s) and should not be con- strued as an official Government position, policy, or decision, unless designated by other documentation. References herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trade mark, manu- facturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by Carnegie Mellon University or its Software Engineering Institute. This report was prepared for the SEI Administrative Agent AFLCMC/AZS 5 Eglin Street Hanscom AFB, MA 01731-2100 NO WARRANTY. THIS CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY AND SOFTWARE ENGINEERING INSTITUTE MATERIAL IS FURNISHED ON AN "AS-IS" BASIS. CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY MAKES NO WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, AS TO ANY MATTER INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, WARRANTY OF FITNESS FOR PURPOSE OR MERCHANTABILITY, EXCLUSIVITY, OR RESULTS OBTAINED FROM USE OF THE MATERIAL. CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY DOES NOT MAKE ANY WARRANTY OF ANY KIND WITH RESPECT TO FREEDOM FROM PATENT, TRADEMARK, OR COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT. [DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A] This material has been approved for public release and unlimited distribu- tion. Please see Copyright notice for non-US Government use and distribution.