Many of Us If Asked to Take Simple Tests to Establish Our Financial Literacy Would Pass on Some and Fail on Others

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias Edited by Peter Ludlow

Ludlow cover 7/7/01 2:08 PM Page 1 Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias Crypto Anarchy, Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias edited by Peter Ludlow In Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias, Peter Ludlow extends the approach he used so successfully in High Noon on the Electronic Frontier, offering a collection of writings that reflect the eclectic nature of the online world, as well as its tremendous energy and creativity. This time the subject is the emergence of governance structures within online communities and the visions of political sovereignty shaping some of those communities. Ludlow views virtual communities as laboratories for conducting experiments in the Peter Ludlow construction of new societies and governance structures. While many online experiments will fail, Ludlow argues that given the synergy of the online world, new and superior governance structures may emerge. Indeed, utopian visions are not out of place, provided that we understand the new utopias to edited by be fleeting localized “islands in the Net” and not permanent institutions. The book is organized in five sections. The first section considers the sovereignty of the Internet. The second section asks how widespread access to resources such as Pretty Good Privacy and anonymous remailers allows the possibility of “Crypto Anarchy”—essentially carving out space for activities that lie outside the purview of nation-states and other traditional powers. The Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, third section shows how the growth of e-commerce is raising questions of legal jurisdiction and taxation for which the geographic boundaries of nation- states are obsolete. The fourth section looks at specific experimental governance and Pirate Utopias structures evolved by online communities. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 464 635 IR 058 441 AUTHOR Lamolinara, Guy, Ed. TITLE The Library of Congress Information Bulletin, 2000. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. ISSN ISSN-0041-7904 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 480p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/. v PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Library of Congress Information Bulletin; v59 n1-12 2000 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Electronic Libraries; *Exhibits; *Library Collections; *Library Services; *National Libraries; World Wide Web IDENTIFIERS *Library of Congress ABSTRACT These 12 issues, representing one calendar year (2000) of "The Library of Congress Information Bulletin," contain information on Library of Congress new collections and program developments, lectures and readings, financial support and materials donations, budget, honors and awards, World Wide Web sites and digital collections, new publications, exhibits, and preservation. Cover stories include:(1) "The Art of Arthur Szyk: 'Artist for Freedom' Featured in Library Exhibition";(2) "The Year in Review: 1999 Marks Start of Bicentennial Celebration"; (3) "'A Whiz of a Wiz': New Library Exhibition on 'The Wizard of Oz' Opens"; (4) "The Many Faces of Thomas Jefferson: Father of the Library Subject of New Exhibition"; (5) Library of Congress bicentennial events; (6) "Thanks for the Memory: New Bob Hope Gallery Opens at Library"; (7) "Local Legacies: American Culture Captured in Bicentennial Program"; (8) "America at Work, School and Play: Web Films Document American Culture, 1894-1915"; (9) "Herblock's History Political Cartoon Exhibition Opens Oct. 17";(10) "Aaron Copland Centennial"; and (11)"Al Hirschfeld: Beyond Broadway: Exhibition of Work by Famed Graphic Artist Open." (Contains 91 references.) MES) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Weblogs and Libraries CHANDOS INFORMATION PROFESSIONAL SERIES

Weblogs and Libraries CHANDOS INFORMATION PROFESSIONAL SERIES Series Editor: Ruth Rikowski (email: [email protected]) Chandos’ new series of books are aimed at the busy information professional. They have been specially commissioned to provide the reader with an authoritative view of current thinking. They are designed to provide easy-to-read and (most importantly) practical coverage of topics that are of interest to librarians and other information professionals. If you would like a full listing of current and forthcoming titles, please visit our web site www.chandospublishing.com or contact Hannah Grace-Williams on email [email protected] or telephone number +44 (0) 1865 884447. New authors: we are always pleased to receive ideas for new titles; if you would like to write a book for Chandos, please contact Dr Glyn Jones on email [email protected] or telephone number +44 (0) 1865 884447. Bulk orders: some organisations buy a number of copies of our books. If you are interested in doing this, we would be pleased to discuss a discount. Please contact Hannah Grace-Williams on email [email protected] or telephone number +44 (0) 1865 884447. Weblogs and Libraries LAUREL A. CLYDE Chandos Publishing Oxford · England · New Hampshire · USA Chandos Publishing (Oxford) Limited Chandos House 5 & 6 Steadys Lane Stanton Harcourt Oxford OX29 5RL UK Tel: +44 (0) 1865 884447 Fax: +44 (0) 1865 884448 Email: [email protected] www.chandospublishing.com Chandos Publishing USA 3 Front Street, Suite 331 PO Box 338 Rollinsford, NH 03869 USA Tel: 603 749 9171 Fax: 603 749 6155 Email: [email protected] First published in Great Britain in 2004 ISBN: 1 84334 085 2 (paperback) 1 84334 096 8 (hardback) © Laurel A. -

2008-2009 Annual Report (Complete Report)

connect Annual Report 2009 engage Re definingthe town square belong improve support Sarah, Victoria and Amy love taking time out from study to catch up on Once, the town square was a all the latest. Whether it’s watching last night’s episode of The Chaser, place where people gathered downloading a triple j pod or vod, to talk and exchange ideas. or grabbing a movie review on ABC Mobile, wherever they are, the ABC is their town square. Now, the ABC is redefining the town square as a world of greater opportunities: a world where Australians can engage with one another and explore the ideas and events that are shaping our communities, our nation and beyond. A world where people can come to speak and be heard, to listen and learn from each other. 2008–09 at a Glance 2 In this report The National Broadcaster 4 Letter of Transmittal 6 Corporate Report 7 SECTION 1 ABC Vision, Mission and Values 7 Corporate Plan Summary 8 ABC Board of Directors 10 Board Directors’ Statement 14 ABC Advisory Council 18 Significant Events in 2008–09 22 The Year Ahead 24 Magazine 25 Overview 38 SECTION ABC Audiences 38 2 ABC Services 53 ABC in the Community 56 ABC People 60 Commitment to a Greener Future 65 Corporate Governance 68 Corporate Sustainability 74 Financial Summary 76 ABC Divisional Structure 79 SECTION ABC Divisions 80 3 Radio 80 Television 85 News 91 Innovation 95 ABC International 98 ABC Commercial 102 Operations Group 106 People and Learning 110 Corporate 112 SECTION 4 Summary Reports 121 Performance Against the ABC Corporate Plan 2007–10 121 Outcomes and Outputs 133 SECTION Independent Auditor’s Report 139 5 Financial Statements 141 Appendices 187 Index 247 Glossary 250 ABC Charter and Duties of the Board 251 1 Radio–8 760 radio hours on each network and station. -

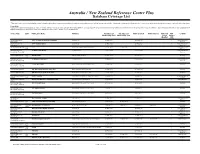

Australia/New Zealand Reference Centre Database Coverage List

Australia/New Zealand Reference Centre Database Coverage List *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN / ISBN Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Full Text Full Text PDF Country Abstracting Abstracting Start Stop Delay Images Start Stop (Months) (full page) International Magazine 1035-6754 21 C Australian Commission for the Future 01-Sep-1994 31-Jan-1998 United States of America International TV & 48 Hours (CBS News) CQ Roll Call Inc. 01-Dec-2000 01-Dec-2000 United States of Radio News Transcript America Australia/NZ Magazine 0726-2418 4X4 Australia ARE Media Pty Limited 01-Feb-2009 01-Feb-2009 Australia International TV & 60 Minutes (CBS News) CQ Roll Call Inc. 26-Nov-2000 26-Nov-2000 United States of Radio News Transcript America Australia/NZ -

Commonwealth Bank of Australia Concise Report 2004

2004 Commonwealth Bank of Australia ACN 123 123 124 Concise Annual Report 2004 Commonwealth Bank of Australia Concise Annual Report 2004 Contents p1 Message from the Chairman p4 Review of Operations p6 Message from the Chief Executive Officer p8 The Bank’s People p10 The Bank and the Community — A Profile p12 Our Directors p16 Corporate Governance p27 Directors’ Report p36 Five Year Financial Summary p39 Business Overview p43 Comments on Statement of Financial Performance p45 Statement of Financial Performance p46 Comments on Statement of Financial Position p47 Statement of Financial Position p48 Statement of Cash Flows p49 Notes to the Financial Statements p73 Directors’ Declaration p74 Independent Audit Report www.amm.com.au p75 Shareholding Information p80 Contact Us Designed and produced by Armstrong Miller+McLaren – Miller+McLaren by Armstrong Designed and produced Message from the Chairman John T Ralph, AC Chairman The Bank experienced another strong year with the Australian economy continuing to perform well. Housing lending remained buoyant for most of the year with early signs of some slowing towards the end of the year. Very low levels of corporate and personal defaults were experienced in a favourable credit environment. Investment markets recovered which led to an improvement in the performance of the funds management and insurance businesses as well as contributing to an increase in the assessed value of the funds management business. The Bank embarked on the three year Which new Bank program during the year, the successful execution of which is critical to the long term success of the Bank. So it is pleasing to be able to report that very good progress was made in the first year of the program in the achievement against the milestones set for the program. -

Australia / New Zealand Reference Centre Plus Database Coverage List

Australia / New Zealand Reference Centre Plus Database Coverage List *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Start Full Text Stop Full Text PDF Country Abstracting Start Abstracting Stop Delay Images (Months) (full page) International Book / 1813 Crossing of the Blue Mountains Salem Press 15-Mar-2017 15-Mar-2017 Y United States of Monograph America International Book / 2000 Olympic Games Salem Press 15-Mar-2017 15-Mar-2017 Y United States of Monograph America International Magazine 1035- 21 C Australian Commission for the Future 01-Sep-1994 31-Jan-1998 United States of 6754 America International TV & 48 Hours (CBS News) CQ Roll Call Inc. 01-Dec-2000 01-Dec-2000 United States of Radio News Transcript America Australia/NZ Magazine 0726- 4X4 Australia ARE Media Pty Limited 01-Feb-2009 01-Feb-2009 Australia 2418 International TV & 60 Minutes (CBS News) CQ Roll Call Inc. -

The Digital Future Is Now

The Annual Report 2008 digital future when you want it podcasts multimedia online entertainment vodcasts mashups more choices sport kids greater coverage regional local more community greater interaction continuous news on demand broadband content live streaming more when you want it is now Four-year-old Ellery just loves having “screen time” so she can show her grandad Graeme around The Playground. Her favourite character is Artie, but she also really likes Ruby. ABC Kids’ new immersive preschool For Ellery and Graeme, the digital future is now. world is fast becoming a favourite online destination for Australian children, recording a 40% increase in traffic since it started. It also acts as a launching pad for other popular television websites such as Playschool, Shaun the Sheep and Bottle Top Bill. 2007–08 at a Glance 2 In this report The National Broadcaster 4 Letter to the Minister 6 Corporate Report 7 SECTION ABC Vision, Mission and Values 7 Significant Events in 2007–08 8 Corporate Plan Summary 0 ABC Board of Directors 2 Board Directors’ Statement 6 ABC Advisory Council 9 The Year Ahead 20 Magazine Section 21 Overview 32 SECTION ABC Audiences 32 2 ABC Services 47 ABC in the Community 50 ABC People 54 Commitment to a Greener Future 59 Corporate Governance 64 Financial Summary 72 ABC Divisional Structure 75 ABC Divisions 76 SECTION Radio and Regional Content 76 3 Television 80 News 86 Innovation 90 International 94 Commercial 98 Operations Group 02 People and Learning 06 Corporate 07 Summary Reports 116 SECTION 4 Performance Against the ABC Corporate Plan 2007–0 116 Outcomes and Outputs 28 Independent Auditor’s Report 39 SECTION Financial Statements 4 5 Appendices 8 Index 235 Glossary 238 ABC Charter and Duties of the Board 239 Radio—8 784 radio hours on each network and station. -

BJMC IV SEM Course-XVII Social Media Social Networking Sites A

BJMC IV SEM Course-XVII Social Media Social Networking Sites A social networking service is a platform to build social networks or social relations among people who share interests, activities, backgrounds or real-life connections. A social network service consists of a representation of each user (often a profile), his or her social links, and a variety of additional services. Social networks are web-based services that allow individuals to create a public profile, to create a list of users with whom to share connections, and view and cross the connections within the system. Most social network services are web-based and provide means for users to interact over the Internet, such as e-mail and instant messaging. Social network sites are varied and they incorporate new information and communication tools such as mobile connectivity, photo/video/sharing and blogging. Online community services are sometimes considered as a social network service, though in a broader sense, social network service usually means an individual-centered service whereas online community services are group-centered. Social networking sites allow users to share ideas, pictures, posts, activities, events, interests with people in their network. The main types of social networking services are those that contain category places (such as former school year or classmates), means to connect with friends (usually with self-description pages), and a recommendation system linked to trust. Popular methods now combine many of these, with American-based services such as Facebook, -

Annual Report No. 31

AUSTRALIAN PRESS COUNCIL Annual Report No. 31 Year ending 30 June 2007 Suite 10.02, 117 York Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Australia Telephone: (02) 9261 1930 or (1800) 025 712 Fax: (02) 9267 6826 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.presscouncil.org.au/ ISSN 0156-1308 Australian Press Council Annual Report 2006-2007 Contents Chairman’s Foreword ...........................................................................3 Free Speech Issues Report on free speech issues ................................................................ 6 Charter of a Free Press in Australia ................................................... 19 Adjudications and Complaints Adjudications Nos 1322 - 1361 ......................................................... 20 Adjudication publication details ........................................................ 41 Complaints/adjudications 1976-2007 ................................................ 42 Index to Adjudications ....................................................................... 43 Complaints/adjudication statistics 2006-2007 ................................... 43 Complaints not adjudicated ............................................................... 46 Changes in principles and procedures ............................................... 50 Statement of Principles ...................................................................... 52 Privacy Standards for the print media ............................................... 53 Complaints procedure ....................................................................... -

Annual Report June 2004

COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA COMMONWEALTH 2004 Commonwealth Bank of Australia ACN 123 123 124 Annual Report 2004 ANNUAL REPORT 2004 Produced by Armstrong Miller+McLaren – www.amm.com.au Commonwealth Bank of Australia ACN 123 123 124 Annual Report 2004 Table of Contents Chairman's Statement.....................................................................................................................................................................3 Highlights ........................................................................................................................................................................................5 Banking Analysis.............................................................................................................................................................................9 Funds Management Analysis........................................................................................................................................................17 Insurance Analysis........................................................................................................................................................................21 Shareholder Investment Returns ..................................................................................................................................................24 Life Company Valuations..............................................................................................................................................................25 -

Annual Report No. 32

AUSTRALIAN PRESS COUNCIL Annual Report No. 32 Year ending 30 June 2008 Suite 10.02, 117 York Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Australia Telephone: (02) 9261 1930 or (1800) 025 712 Fax: (02) 9267 6826 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.presscouncil.org.au/ ISSN 0156-1308 Australian Press Council Annual Report 2007-2008 Contents Chairman’s Foreword ...........................................................................3 Free Speech Issues Report on free speech issues ................................................................ 5 Charter of a Free Press in Australia ................................................... 23 Adjudications and Complaints Adjudications Nos 1362 - 1396 ......................................................... 24 Adjudication publication details ........................................................ 45 Complaints/adjudications 1976-2008 ................................................ 46 Index to Adjudications ....................................................................... 46 Complaints/adjudication statistics 2007-2008 ................................... 47 Complaints not adjudicated ............................................................... 50 Changes in principles and procedures ............................................... 51 Statement of Principles ...................................................................... 52 Privacy Standards for the print media ............................................... 53 Complaints procedure .......................................................................