L.D. INSTITUTE of INDOLOGY AHMEDABAD Published by

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q3t1s0 Author Balachandran, Jyoti Gulati Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Chair This dissertation examines the processes through which a regional community of learned Muslim men – religious scholars, teachers, spiritual masters and others involved in the transmission of religious knowledge – emerged in the central plains of eastern Gujarat in the fifteenth century, a period marked by the formation and expansion of the Gujarat sultanate (c. 1407-1572). Many members of this community shared a history of migration into Gujarat from the southern Arabian Peninsula, north Africa, Iran, Central Asia and the neighboring territories of the Indian subcontinent. I analyze two key aspects related to the making of a community of ii learned Muslim men in the fifteenth century - the production of a variety of texts in Persian and Arabic by learned Muslims and the construction of tomb shrines sponsored by the sultans of Gujarat. -

Oswal Auction 12

Oswal Antiques’ AUCTIONS Auctioneer of Coins, Bank Notes and Medals Antiques License No. 15 Auction No. 12 On Thursday, 22nd April 2010 2 Vaishakha, VS 2066; Jain Vir Samvat 2536 9 Jumada I, AH 1431 6.00 pm onwards At Tejpal Hall, Opp. August Kranti Maidan, Gowalia Tank, Grant Road, Mumbai Shop No. 2, Chandra Mahal, St. Paul Street, Dadar, Hindmata, Mumbai 400014. India .www.oswalauctions.com “Buyer's Premium” is 11.03 % (Including Service Tax) VAT TIN: 27280578593V • CST TIN: 27280578593C Organized by: VAT 1% on Silver and Gold items Oswal Antiques 5% on other metal items • No VAT on Paper Money Girish J. Veera Service Tax No.: AACPV0832DST001 Shop No. 2, Chandra Mahal, St. Paul Street, Dadar, Hindmata, Mumbai 400014. India Our Bankers: ICICI Bank, Dadar Branch, Mumbai By Appointment (11 am to 5 pm) Oswal Antiques: A/c No. 003205004383 Phone: 022-2412 6213 • 2412 5204 Public View: 22nd April, 11:00 pm - 3:00 pm; Fax: 022-2414 9917 Mobile No: 093200 10483 At the Venue E-mail: [email protected] By Appointment: [email protected] 19 to 21April 2010 Website: www.oswalauctions.com 3:00 - 6:00 pm (by Appointment) www.indiacoingallery.com At Our Mumbai Office Catalogue Prepared by: Dr. Dilip Rajgor Design & Layout: Reesha Books International (022-2561 4360) Rs. 200 Photography by: Satessh Gupta Ancient Coins 5 Indo-Greeks, Menander I, Silver (2), Drachm, diademed bust to right and bust to left wielding a spear types. About Very Fine, Scarce. 2 coins Estimate: Rs. 2,500-3,000 1 Punch-marked coins, Gandhara Janapada, Silver (4), Bent Bar, 11.32 and 9.79 g, the first is of fine silver whereas the second is silver-plated 6 Indo-Greeks, Menander I, Silver (3), Drachm, copper; single punch type, 1.27 and 0.44 g, four diademed bust to right and bust to left wielding a different denominations (Rajgor 2001). -

E-Auction # 28

e-Auction # 28 Ancient India Hindu Medieval India Sultanates of India Mughal Empire Independent Kingdom Indian Princely States European Colonies of India Presidencies of India British Indian World Wide Medals SESSION I SESSION II Saturday, 24th Oct. 2015 Sunday, 25th Oct. 2015 Error-Coins Lot No. 1 to 500 Lot No. 501 to 1018 Arts & Artefects IMAGES SHOWN IN THIS CATALOGUE ARE NOT OF ACTUAL SIZE. IT IS ONLY FOR REFERENCE PURPOSE. HAMMER COMMISSION IS 14.5% Inclusive of Service Tax + Vat extra (1% on Gold/Silver, 5% on other metals & No Vat on Paper Money) Send your Bids via Email at [email protected] Send your bids via SMS or WhatsApp at 92431 45999 / 90084 90014 Next Floor Auction 26th, 27th & 28th February 2016. 10.01 am onwards 10.01 am onwards Saturday, 24th October 2015 Sunday, 25th October 2015 Lot No 1 to 500 Lot No 501 to 1018 SESSION - I (LOT 1 TO 500) 24th OCT. 2015, SATURDAY 10.01am ONWARDS ORDER OF SALE Closes on 24th October 2015 Sl.No. CATEGORY CLOSING TIME LOT NO. 1. Ancient India Coins 10:00.a.m to 11:46.a.m. 1 to 106 2. Hindu Medieval Coins 11:47.a.m to 12:42.p.m. 107 to 162 3. Sultanate Coins 12:43.p.m to 02:51.p.m. 163 to 291 4. Mughal India Coins 02:52.p.m to 06:20.p.m. 292 to 500 Marudhar Arts India’s Leading Numismatic Auction House. COINS OF ANCIENT INDIA Punch-Mark 1. Avanti Janapada (500-400 BC), Silver 1/4 Karshapana, Obv: standing human 1 2 figure, circular symbol around, Rev: uniface, 1.37g,9.94 X 9.39mm, about very fine. -

Rita Kothari.P65

NMML OCCASIONAL PAPER PERSPECTIVES IN INDIAN DEVELOPMENT New Series 47 Questions in and of Language Rita Kothari Humanities and Social Sciences Department, Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar, Gujarat Nehru Memorial Museum and Library 2015 NMML Occasional Paper © Rita Kothari, 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of the contents may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author. This Occasional Paper should not be reported as representing the views of the NMML. The views expressed in this Occasional Paper are those of the author(s) and speakers and do not represent those of the NMML or NMML policy, or NMML staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide support to the NMML Society nor are they endorsed by NMML. Occasional Papers describe research by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. Questions regarding the content of individual Occasional Papers should be directed to the authors. NMML will not be liable for any civil or criminal liability arising out of the statements made herein. Published by Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Teen Murti House New Delhi-110011 e-mail : [email protected] ISBN : 978-93-83650-63-7 Price Rs. 100/-; US $ 10 Page setting & Printed by : A.D. Print Studio, 1749 B/6, Govind Puri Extn. Kalkaji, New Delhi - 110019. E-mail : [email protected] NMML Occasional Paper Questions in and of Language* Rita Kothari Sorathgada sun utri Janjhar re jankaar Dhroojegadaanrakangra Haan re hamedhooje to gad girnaar re… (K. Kothari, 1973: 53) As Sorath stepped out of the fort Not only the hill in the neighbourhood But the walls of Girnar fort trembled By the sweet twinkle of her toe-bells… The verse quoted above is one from the vast repertoire of narrative traditions of the musician community of Langhas. -

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century Thesis submitted for the dc^ee fif DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY By AJAZ BANG Under the supervision of PROF. IQTIDAR ALAM KHAN Department of History Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarb- 1983 T388S 3 0 JAH 1392 ?'0A/ CHE':l!r,D-2002 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY TELEPHONE SS46 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that the thesis entitled 'Soci•-Political Condition Ml VB Wtmmimt of Gujarat / during the fifteenth Century' is an original research work carried out by Aijaz Bano under my Supervision, I permit its submission for the award of the Degree of the Doctor of Philosophy.. /-'/'-ji^'-^- (Proi . Jrqiaao;r: Al«fAXamn Khan) tc ?;- . '^^•^\ Contents Chapters Page No. I Introduction 1-13 II The Population of Gujarat Dxiring the Sixteenth Century 14 - 22 III Gujarat's External Trade 1407-1572 23 - 46 IV The Trading Cotnmxinities and their Role in the Sultanate of Gujarat 47 - 75 V The Zamindars in the Sultanate of Gujarat, 1407-1572 76 - 91 VI Composition of the Nobility Under the Sultans of Gujarat 92 - 111 VII Institutional Featvires of the Gujarati Nobility 112 - 134 VIII Conclusion 135 - 140 IX Appendix 141 - 225 X Bibliography 226 - 238 The abljreviations used in the foot notes are f ollov.'ing;- Ain Ain-i-Akbarl JiFiG Arabic History of Gujarat ARIE Annual Reports of Indian Epigraphy SIAPS Epiqraphia Indica •r'g-acic and Persian Supplement EIM Epigraphia Indo i^oslemica FS Futuh-^ffi^Salatin lESHR The Indian Economy and Social History Review JRAS Journal of Asiatic Society ot Bengal MA Mi'rat-i-Ahmadi MS Mirat~i-Sikandari hlRG Merchants and Rulers in Giijarat MF Microfilm. -

Auction No 6 Session I Saturday, 29 April 2017 04:30 Pm Onwards Session II Sunday, 30 April 2017 11:00 Am Onwards

OUR SPECIALIST TEAM : Raghunadha Raju Punch Mark Coinage [email protected] Foreign Coinage Coinage of the East India Company Prakash Jinjuvadiya Ancient Indian Coinage [email protected] Coinage of the Gujarat States Portuguese Indian Coinage Rajesh Nair Ancient Indian Coinage [email protected] Coinage of the Medieval Indian Kingdoms Coinage of the European Powers in India Pundalik Baliga Coinage of the Medieval Indian Kingdoms [email protected] Coinage of the Independent Kingdoms Coinage of the Republic India Western Kshatrapa Coinage Mohit Kapoor Coinage of the Mughal Empire [email protected] Coinage of the Independent Kingdoms Coinage of the Indian Princely States Coinage of the European Powers in India Medals ACADEMIC ADVISOR : Mr. Jan Lingen (Netherlands) Auction No 6 Session I Saturday, 29 April 2017 04:30 pm onwards Session II Sunday, 30 April 2017 11:00 am onwards A Comprehensive Auction of Coins, Banknotes and Medals Venue : Internet for bidding online on the internet: www.imperialauctions.com or download our mobile app from Android: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.jestro.auction iOS: https://itunes.apple.com/in/app/imperial-auctions/id1177681595?mt=8 01 Order of Sale : Auction # 6 Session 1 Saturday, 29th April 2017 04:30 PM onwards Ancient Lots 1- 172 Medieval Kingdoms Lots 173 - 205 Sultanates Lots 206 - 234 Shop # 1, Naveena Apartment, Yeshwant Nagar, Mughal Empire Lots 235 - 409 Telco Road, Pimpri, Pune – 411 018, Maharashtra. Independent Kingdoms Lots 410 - 551 Telephone: +91 20 27460696. Fax: +91 22 25500595 Princely States Lots 552 - 664 Auction # 6 Session 2 Sunday, 30th April 2017 11:00 AM onwards European Colonial Coins Lots 665 - 731 British India Lots 732 - 770 Republic India Lots 771 - 778 Foreign Coins Lots 779 - 843 Medals and Badges Lots 844 - 876 01 Paper Money Lots 877 - 899 Legal : Buyers Premium : CIN : U74900PN2015PTC154109 Gajalakshmi Associates P. -

Online Exhibition | Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture | 2020

Online Exhibition | Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture | 2020 Stepwells of Ahmedabad The settlement pattern of north central Gujarat evolved in response to its undulating terrain and was deeply influenced by the collection, preservation, and use of water (see Gallery 1). The travel routes that linked these settlements also followed paths charted by the seasonal movement of water across the region’s wrinkled, semi-arid landscape. The settlements formed a network tying major cities and port towns to small agricultural and artisanal villages that collectively constituted the region’s productive hinterland. The city of Ahmedabad, which emerged on the Sabarmati River, was an historic center of this network. The Sabarmati river originates in the Aravalli hills in the northeast, meanders through the gently undulating alluvial plains of north central Gujarat, and finally merges with the Arabian Sea at the Gulf of Khambhat in the south. About 50 miles north of the port city of Khambhat, Sultan Ahmad Shah, the ruler of the Gujarat Sultanate, built a citadel along the Sabarmati in 1411, formally establishing the city of Ahmedabad. The citadel was strategically situated on the river’s elevated eastern bank, anticipating the settlement’s future eastward expansion.1 Strategic elevations in the undulating terrain were identified as areas for dwelling.2 As a seasonal river, the Sabarmati swells during the monsoon and contracts in the summer, leaving dry large swathes. During its dry period, the riverbed became an expansive public space, bustling with temporary markets, circuses, and seasonal farming, as well as a variety of human activities such as washing, dyeing, and drying textiles.3 Soon after its establishment, Ahmedabad emerged as the region’s administrative capital and as an important node in the Indian Ocean trade network. -

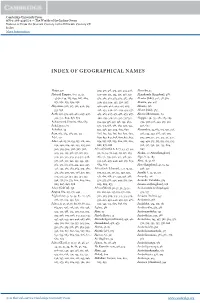

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

Historic City of Ahmadabad India

HISTORIC CITY OF AHMADABAD INDIA NOMINATION DOSSIER FOR INSCRIPTION ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation Prepared by Centre for Conservation Studies, CEPT University January 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY STATE PARTY : India STATE, PROVINCE OR REGION : Gujarat NAME OF PROPERTY : Historic City Of Ahmadabad GEOGRAPHICAL COORDINATES : Centre Point : 23° 01’ 35”N Latitude, 72° 35’ 17”E Longitude TEXTUAL DESCRIPTION OF THE BOUNDARY(IES) OF THE NOMINATED PROPERTY : The entire area of the Historic city of Ahmadabad formerly enclosed within the city walls including the city gates, fragments of fortification and the footprints of the demolished walls. MAP WITH BOUNDARIES : Attached CRITERIA UNDER WHICH PROPERTY IS NOMINATED : Criteria (ii) (v) (vi) DRAFT STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE BRIEF SYNTHESIS The entire walled city exhibits Universal significance and therefore the entire historic urban landscape of the Old City of Ahmadabad is taken into consideration in the preparation of the nomination. The architecture of the Sultanate period monuments exhibit a unique fusion of the multi-cultural character of the historic city, and its significance is highlighted in preparing the nomination to the World Heritage List. This heritage, which comes under the protection of the ASI, is of great national importance and is associated with the complementary traditions embodied in other religious buildings and the old city’s very rich domestic wooden architecture so as to illustrate the World Heritage significance of Ahmedabad. The urban structure of the historic city as represented by its discrete plots of land is proposed to be protected, since this records its heritage in the form of the medieval town plan and its settlement patterns. -

Indian Culture (Semester System) B

SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY NEW REVISED SYLLABUS INDIAN CULTURE (SEMESTER SYSTEM) B. A. Semester 1 TO 6 Under Graduate PAPER NO. 1 TO 22 Code: JUNE-2016 Page 1 of 111 Saurashtra University, Rajkot Arts Faculty Subject: INDIAN CULTURE SEMESTER: I to VI Sr. LEVEL Semes Course Course(Paper) Title Pap Credit Internal External Pract Total Course (Paper) No UG/PG/M.Phil ter Group er Mark Mark ical/ Marks Unique Code . etc. Core/El No. Viva e1 Mark /Ele2 s (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) 1 Under Graduate 1 Core Cultural History of India – 1 3 30 70 - 1 Ancient period. ૦૦ 1601280101010100 2 Under Graduate 1 ELE::I Cultural History of India - 1 3 30 70 - 1 Ancient period. ૦૦ 1601280201010100 3 Under Graduate 1 ELE::II Cultural History of India - 1 3 30 70 - 1 Ancient period. ૦૦ 1601280301010100 4 Under Graduate 1 Core Cultural History of Gujarat - 2 3 30 70 - 1૦૦ Ancient period 1601280101010200 5 Under Graduate 1 ELE::I Cultural History of Gujarat - 2 3 30 70 - 1૦૦ Ancient period 1601280201010200 6 Under Graduate 1 ELE::II Cultural History of Gujarat - 2 3 30 70 - 1૦૦ Ancient period 1601280301010200 7 Under Graduate 2 Core Cultural History of India - 3 3 30 70 - 1 Ancient period. ૦૦ 1601280101020300 8 Under Graduate 2 ELE::I Cultural History of India - 3 3 30 70 - 1 Ancient period. ૦૦ 1601280201020300 Page 2 of 111 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) 9 Under Graduate 2 ELE::II Cultural History of India - 3 3 30 70 - 1 Ancient period. -

The Shaping of Modern Gujarat

A probing took beyond Hindutva to get to the heart of Gujarat THE SHAPING OF MODERN Many aspects of mortem Gujarati society and polity appear pulling. A society which for centuries absorbed diverse people today appears insular and patochiai, and while it is one of the most prosperous slates in India, a fifth of its population lives below the poverty line. J Drawing on academic and scholarly sources, autobiographies, G U ARAT letters, literature and folksongs, Achyut Yagnik and Such Lira Strath attempt to Understand and explain these paradoxes, t hey trace the 2 a 6 :E e o n d i n a U t V a n y history of Gujarat from the time of the Indus Valley civilization, when Gujarati society came to be a synthesis of diverse peoples and cultures, to the state's encounters with the Turks, Marathas and the Portuguese t which sowed the seeds ol communal disharmony. Taking a closer look at the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the authors explore the political tensions, social dynamics and economic forces thal contributed to making the state what it is today, the impact of the British policies; the process of industrialization and urbanization^ and the rise of the middle class; the emergence of the idea of '5wadeshi“; the coming £ G and hr and his attempts to transform society and politics by bringing together diverse Gujarati cultural sources; and the series of communal riots that rocked Gujarat even as the state was consumed by nationalist fervour. With Independence and statehood, the government encouraged a new model of development, which marginalized Dai its, Adivasis and minorities even further. -

View Syllabus

BA HISTORY HONOURS AND BA PROGRAMME IN HISTORY 1ST SEMESTER PAPERS B.A. HISTORY HONOURS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, DELHI UNIVERSITY Core Course I History of India- I Course Objectives: Being the first paper of the History Honours course, it intends to provide an extensive survey of early Indian history to the students and familiarise them with the tools of studying ancient Indian history. The inter-disciplinary approach of the course provides the students a point of beginning from where they can build an understanding of the discipline of history. Spanning a very long period of India’s ancient past – from pre- historic times to the end of Vedic cultures in India – the course dwells upon major landmarks of ancient Indian history from the beginning of early human hunter gatherers to food producers. This course will equip the students with adequate expertise to analyse the further development of Indian culture which resulted in an advanced Harappan civilization. In course of time students will learn about the processes of cultural development and regional variations. Learning Outcomes: After completing the course the students will be able to: Discussthe landscape and environmental variations in Indian subcontinent and their impact on the making of India’s history. Describe main features of prehistoric and proto-historic cultures. List the sources and evidence for reconstructing the history of Ancient India Analyse the way earlier historians interpreted the history of India and while doing so they can write the alternative ways of looking at the past. List the main tools made by prehistoric and proto- historic humans in India along with their find spots.