729-Doc-11.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International-Religious-Freedom-Report Yemen-2018

YEMEN 2018 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution declares Islam the state religion and sharia the source of all legislation. It provides for freedom of thought and expression “within the limits of the law” but does not mention freedom of religion. The law prohibits denunciation of Islam, conversion from Islam to another religion, and proselytizing directed at Muslims. The conflict that broke out in 2014 between the government, led by President Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi, and Houthi-led Ansar Allah, a Zaydi Shia movement, continued through year’s end. While the president, vice president, and foreign minister remained in exile in Saudi Arabia, the remainder of the cabinet moved to Aden in October. The government did not exercise effective control over much of the country’s territory. Although causes for the war were complex, sectarian violence accompanied the civil conflict, which observers described as “part of a regional power struggle between Shia-ruled Iran and Sunni-ruled Saudi Arabia.” In January the Houthi-controlled National Security Bureau (NSB) sentenced to death Hamed Kamal Muhammad bin Haydara, a Baha’i, on charges of espionage. He had been imprisoned since 2013, accused of apostasy, proselytizing, and spying for Israel. He remained in prison awaiting execution at year’s end. According to the Baha’i International Community (BIC), in October armed soldiers in Sana’a arrested Baha’i spokesperson Abdullah Al-Olofi and detained him at an undisclosed location for three days. According to the BIC, in September a Houthi- controlled court in Sana’a charged more than 20 Baha’is with apostasy and espionage. -

IPEC Evaluation

IPEC Evaluation National Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour in Yemen YEM/00/P50/USA An independent final evaluation by a team of external consultants January 2006 i National Programme for the Elimination of Child Labour in Yemen. NOTE ON THE EVALUATION PROCESS AND REPORT This independent evaluation was managed by ILO-IPEC’s Design, Evaluation and Documentation Section (DED) following a consultative and participatory approach. DED has ensured that all major stakeholders were consulted and informed throughout the evaluation and that the evaluation was carried out to highest degree of credibility and independence and in line with established evaluation standards. The evaluation was carried out a team of external consultants1. The field mission took place in January 2006. The opinions and recommendations included in this report are those of the authors and as such serve as an important contribution to learning and planning without necessarily constituting the perspective of the ILO or any other organization involved in the project. Funding for this project evaluation was provided by the United States Department of Labor. This report does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Department of Labor nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. 1 Andrea Hitzemann ii National Programme for the Elimination of Child Labour in Yemen. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ -

United States of America: the Issue of Extrajudicial Killings in Yemen

United States of America: The issue of extrajudicial killings in Yemen Report submitted to the Human Rights Committee in the context of the review of the fourth periodic report of the United States of America 30 August 2013 Alkarama – 2bis Chemin des Vignes – 1209 Geneva – Switzerland +41 22 734 10 06 – F +41 22 734 10 34 - Email: [email protected] – Url: www.alkarama.org About Alkarama Alkarama is a registered Swiss foundation headquartered in Geneva, established in 2004 by volunteer human rights lawyers and defenders. It works on human rights violations in the Arab world with offices and representatives in Lebanon (Beirut), Qatar (Doha), Cairo (Egypt) and Yemen (Sana’a). Its work focuses on four priority areas: extra-judicial executions, disappearances, torture and arbitrary detention. Related activities include protecting human rights defenders and ensuring the independence of judges and lawyers. Alkarama engages with the United Nations (UN) human rights mechanisms. It has submitted thousands of cases and urgent appeals to the Special Procedures of the UN, the Special Rapporteur on Torture, the High Commissioner for Human Rights and various UN human rights treaty bodies. Additionally, Alkarama has submitted numerous reports on the human rights situation in the Arab states reviewed under the Universal Periodic Review, and to the UN Special Procedures and human rights treaty bodies. Basing its work on principles of international human rights law and humanitarian law, Alkarama uses UN human rights mechanisms on behalf of victims of human rights violations and their families. It works constructively with sovereign states, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and national human rights institutions, as well as victims’ lawyers and human rights defenders. -

Evaluation of EU Cooperation with Yemen 2002-12 Final Report Volume II – Annexes March 2015 ______Evaluation Carried out on Behalf of the European Commission

Evaluation of EU Cooperation with Yemen 2002-12 Final Report Volume II – Annexes March 2015 ___________ Evaluation carried out on behalf of the European Commission Development and Cooperation EuropeAid Consortium composed by ADE, COWI Leader of the Consortium: ADE Contact Person: Edwin CLERCKX [email protected] Framework Contract No EVA 2011/Lot 4 Specific Contract N°2012/306861/2 Evaluation of EU Cooperation with Yemen 2002-12 This evaluation was commissioned by the Evaluation Unit of the Directorate-General for Development and Cooperation – EuropeAid (European Commission) Due to the prevailing security situation in 2014, this evaluation was undertaken without a field phase on the ground in Yemen Team: Dane Rogers (Team Leader), Ginny Hill, Jon Bennett, Helen Lackner, Rana Khalil, David Fleming This report has been prepared in collaboration with 12 English Business Park, English Close, Hove, BN3 7ET United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)1273 765250 Fax: +44 (0)1273 765251 Email: [email protected] www.itad.com The opinions expressed in this document represent the authors’ points of view, which are not necessarily shared by the European Commission or by the authorities of the countries involved. © Cover picture right: Sana’a bab al yemen. Photo Credit: Helen Lackner Evaluation of EU Cooperation with Yemen Final Report – Annexes – March 2015 Evaluation of EU Cooperation with Yemen Final Report – Annexes – March 2015 Evaluation of EU Cooperation with Yemen Final Report Annexes, March 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1: Annexes framing the evaluation ................................................................................................. 1 Annex 1: Evaluation Terms Of Reference .......................................................................................... 3 Annex 2: Evaluation Questions with Judgement Criteria, Indicators and Methods ........................ -

Yemen National Iodine Deficiency Survey 2015

Republic of Yemen Ministry of Public Health and Population Yemen National Iodine Deficiency Survey 2015 i Yemen National Iodine Deficiency Survey 2015 For additional information on this study, Contact Details: Nagib Abdulbaqi A. Ali Nutrition Specialist/ YCSD Section Email: [email protected] Name: Linna Abdullah Al-Eryani Ministry of Public Health and Population Designation: Head of Nutrition Department Email: [email protected] ii iii Contents Acronyms ................................................................................................................................... v Background ................................................................................................................................ 1 Survey objectives ................................................................................................................... 1 The methodology ....................................................................................................................... 2 Sample design and size .......................................................................................................... 3 Training and field procedures ................................................................................................ 4 Handling of urine specimens and salt samples....................................................................... 6 Lab tests of urine and salt and interpretation of readings ...................................................... 6 Data entry, cleaning and analysis .......................................................................................... -

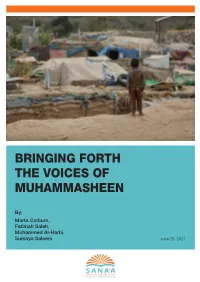

Bringing Forth the Voices of Muhammasheen

BRINGING FORTH THE VOICES OF MUHAMMASHEEN By: Marta Colburn, Fatimah Saleh, Mohammed Al-Harbi, Sumaya Saleem June 28, 2021 BRINGING FORTH THE VOICES OF MUHAMMASHEEN By Marta Colburn, Fatimah Saleh, Mohammed Al-Harbi and Sumaya Saleem June 18, 2021 ALL PHOTOS IN THIS REPORT WERE TAKEN FOR THE SANA’A CENTER AT AL-BIRIN MUHAMASHEEN CAMP, WEST OF TAIZ CITY, ON FEBRURARY ,21 2021, BY AHMED AL-BASHA. The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally. © COPYRIGHT SANA´A CENTER 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................. 5 ACRONYMS ..................................................................................... 6 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...............................................................8 II. HISTORICAL AND SOCIAL CONTEXT ...................................... 14 2.1 Terminology ...........................................................................15 2.2 Demographics and Migration ............................................... 18 2.3 Theories on the Origins of Muhammasheen...........................21 III. Key Research Findings: The Impact of the Conflict on Muhammasheen ........................................................................... -

Security Council Distr.: General 27 July 2018

United Nations S/2018/705 Security Council Distr.: General 27 July 2018 Original: English Letter dated 16 July 2018 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to transmit herewith the twenty-second report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team pursuant to resolutions 1526 (2004) and 2253 (2015), which was submitted to the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities, in accordance with paragraph (a) of annex I to resolution 2368 (2017). I should be grateful if the present letter and the report could be brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Kairat Umarov Chair Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities 18-10599 (E) 090818 *1810599* S/2018/705 Letter dated 27 June 2018 from the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team in accordance with paragraph (a) of annex I to resolution 2368 (2017) addressed to the Chair of the Security Council -

Rada Integrated Rural Development Project

825 YEAL90 ilaco Republic of Yemen / Kingdom of the Netherlands Rada Integrated Rural Development Project LIBRARY INTFRNVTIONAi; REFERENCE FOR COMMUNITY WATER SUPPLY SANITATION (IRC) INVENTORY STUDY REPORT PHASE I 4.08.046 November 1990 Republic of Yemen Kingdom of The Netherlands Ministry of Agriculture Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Water Resources Development Cooperation (Asia) Department INVENTORY STUDY REPORT PHASE I 4.08.046 November 1990 LIBRARY, INTERNATIONAL RCFEP'B'CE C£i,T"" ?C9 -:-:.;MMUNITY WATER SUPPLY P.O. cc •:<•.'• .--, 2bO9 AD The Hagu« :-• "u.:l. (070) 31 4y M ext 141/142 I1!?.' Ilaco Arnhem, The Netherlands INVENTORY STUDY, REPORT PHASE I Page INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Interpretation of the terms of reference 1 1.3 Limitations of the study 4 1.4 Presentation of this report 4 METHODOLOGY OF PHASE I 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Preparatory phase 7 2.3 The quick survey 8 2.4 Methodology of village inquiries 9 2.5 Reports on the field visits 10 2.6 Logistics of phase I 10 SELECTION CRITERIA 11 3.1 Assessment 11 3.2 Selection criteria 11 3.3 Selection of subcriteria 13 3.4 Definitions and use of criteria '**" 14 3.5 Appraisal of criteria ~ 17 3.6 Priority classification 18 4. RESULTS OF SCORING 19 4.1 Scoring of criteria and development potential 19 4.2 Result of priority classification 20 4.3 Selection of areas 23 THEMATIC STUDIES 27 5.1 Need for thematic studies 27 5.2 Water resources maia&ement 27 5.3 Agricultural zoning 29 5.4 Women impact assessment 31 5.5 Migration and off-farm employment 32 5.6 Institutional environment 32 6. -

Mental Health in the Eastern Mediterranean Region Reaching the Unreached

WHO Regional Publications, Eastern Mediterranean Series 29 Mental health in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: reaching theunreached reaching Mediterranean Region: Mental health intheEastern Mental health in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: reaching the unreached Mental health in the In 2001 mental health was brought to the focus of international attention when the World Health Organization devoted its World Health Day campaign and The world health report to the subject. In many countries around the world, and particularly in Eastern Mediterranean Region developing countries, mental health has long been a neglected area of health care, more often than not considered in terms of institutions and exclusion, rather than the care and needs of the human being. Current knowledge emphasizes early identification Reaching the unreached and intervention, care in the community and the rights of mentally ill individuals. The countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region represent many challenges for the organization of mental health care. Many countries are in a state of rapid social change, some are in conflict or suffering the aftermath of conflict, while others are witnessing the growing problem of substance abuse, with associated HIV/AIDS rapidly becoming a public health priority. This publication addresses three aspects: the planning of mental health services; the current mental health situation in each of the countries of the Region, along with the innovative approaches developed during the past two decades, and the challenges and opportunities for addressing the mental health needs of the diverse populations. Bringing together the experiences of the Region provides an opportunity to learn from the past as well as for greater collaboration and cooperation in the future between countries facing similar problems. -

Sanaá Hub Emergency Food Assistance

Yemen Sanaá Humanitarian Hub: District Level 4W/Emergency Food Assistance (In Kind, Cash, & Voucher Transfers) Response and Gap Analysis - May 2019 Emergency Food Assistance & Gap Analysis 124% Bani Al Harith 8% FSAC Partners % ASSISTED 58% People Targeted in Amanat Al Asimah Sanaá hub Sa'ada in Sanaá hub BY GOVERNORATE Hamdan Targeted in Sanaá hub Bani Hushaysh 16 Ath'thaorah 89% 3 Million Al Bayda 99% 167% *PARTNERS THAT REPORTED Amanat Alasimah 122% 107% Shu'aub People Assisted 92% Amran 89% Assisted FOR THE MONTH OF May Ma'ain in Sana’a Dhamar 41% 107% Old City 114% Sana'a 121% Marib 149% At Tahrir Az'zal 2.7 Million Sanaá 93% PERCENTAGE OF PEOPLE ASSISTED PEOPLE OF PERCENTAGE Al Wahdah Assafi'yah Amran 125% 104% 129% Districts In kind (Food) Cash Voucher Bani Matar Al Ashah WFP/CARE As Sabain Al Madan WFP/CARE Al96% Jawf Sanhan Al Qaflah WFP/CARE 94% 123% Amran WFP/SFHRP Harf Sufyan As Sawd WFP/IRY 107% Al Ashah As Sudah WFP/IRY 125% Amran Bani Suraim WFP/IRY Amanat Al Asimah Al Qaflah 98% Dhi Bin WFP/SFHRP Districts In kind (Food) Cash Voucher Marib 61% Huth Harf Sufyan WFP/CARE Al Wahdah WFP/SFHRP Districts In kind (Food) Cash Voucher Huth WFP/CARE As Sabain WFP/SFHRP AFDC, RHD Al Madan Al Abdiyah WFP/IRY Iyal Surayh WFP/SFHRP Assafi'yah WFP/SFHRP AFDC Shaharah Al Jubah WFP/IRY 86% Jabal Iyal Yazid WFP/CARE At Tahrir WFP/SFHRP Bidbadah WFP/IRY 113% 100% Khamir WFP/IRY Ath'thaorah WFP/NRC Bani Suraim Harib WFP/IRY Kharif WFP/SFHRP Az'zal WFP/NRC Suwayr Harib Al Qaramish WFP/SFHRP ADRA Habur Zulaymah Maswar WFP/IRY Bani Al Harith WFP/NRC -

FSAC Sana'á Hub District Level 4W Cash for Work & Livelihoods

YEMEN Sana’a Hub: District Level 4W Conditional Cash Transfers / Cash for Work & Livelihoods Assistance Gap Analysis - July 2019 Livelihoods Assistance & Conditional Cash Gap Analysis 3% Bani Al Harith People Targeted in FSAC Partners % ASSISTED 0% in Sanaá Hub BY GOVERNORATE Amanat Al Asimah Sanaá Hub Sa'ada Hamdan Targeted in Sanaá hub Bani Hushaysh 72% 12 Al Bayda 50% Ath'thaorah 4 Million 0% 1% Amanat Alasimah 1% 0% *PARTNERS THAT REPORTED 0% People Assisted Amran 104% Shu'aub Assisted FOR THE MONTH OF JUN Ma'ain in Sana’a Hub Dhamar 32% 0% Old City 3% Sana'a Marib 39% At Tahrir 0% Az'zal 1.1 Million 28% Sanaá 2% PERCENTAGE OF PEOPLE ASSISTED PEOPLE OF PERCENTAGE Al Wahdah Assafi'yah 0% Amran 0% 1% Bani Matar Short Term Longer Term As Sabain District Name Cash For Work Sanhan Livelihoods AlLivelihoods Jawf 16% 0% Al Ashah FAO/MAI 131% Al Madan FAO/MAI Harf Sufyan Al Qaflah FAO/MAI 219% Al Ashah Amran FAO/MAI SFD 212% Amran Amanat Al Asimah As Sawd FAO/MAI Al Qaflah 197% Short Term Longer Term As Sudah FAO/MAI District Name Cash For Work 73% Huth Livelihoods Livelihoods Bani Suraim FAO/AF - - Al Madan Az'zal - - SFD Dhi Bin FAO/AF - - As Sabain SFD Habur Zulaymah FAO/MAI Shaharah Ath'thaorah SFD Harf Sufyan FAO/MAI 396% 87% Bani Suraim Bani Al Harith FAO/GHFD FAO/GHFD SFD, FAO/WUAs Huth FAO/MAI Shu'aub - - SFD Iyal Surayh FAO/MAI Suwayr 94% Habur Zulaymah Jabal Iyal Yazid FAO/GHFD - - 125% Dhi Bin 119% Khamir Khamir FAO/GHFD - - 106% Kharif FAO/MAI As Sudah 92% 50% Maswar FAO/MAI SFD Iyal Surayh Raydah FAO/MAI 190% Kharif Raydah Majzar -

Icsp-Funded Projects

INSTRUMENT CONTRIBUTING TO STABILITY AND PEACE (IcSP) Report generated: 02/10/2021 Countries: All Themes: All Years: All Supporting Political Accommodation in the Republic of the Sudan Location: Sudan Implementing Conflict Dynamics International partner: Project duration: 02/03/2018 - 01/09/2019 Project Theme: Conflict prevention and resolution, peace-building and security EU Funding: EUR 800 000 Contract number: The people of the Sudan have endured violent crises for over 60 years. With the easing of US sanctions and the upcoming 2020 elections, there is a window of opportunity to accommodate the diverse political interests of the people and their representatives. With funding through the IcSP, Conflict Dynamics International is working with the government, opposition groups as well as with regional and international actors to implement options for effective political dialogue and governance 1 / 405 arrangements. Political representatives are given the tools to reach a sufficient degree of consensus, and encouraged to explore inclusive and coherent political processes. This is being achieved through a series of seminars and workshops (with a range of diverse stakeholders). Technical support is provided to the government as well as to main member groups within the opposition, and focus group discussions are being conducted with influential journalists and political actors at a national level. Regional and international actors are being supported in their efforts to prevent and resolve conflict through a number of initiatives. These include organising at least two coordination meetings, the provision of technical support to the African Union High-Level Implementation Panel, and consultations with groups active in the peace process. Through this support, the action is directly contributing to sustainable peace and political stability in Sudan and, indirectly, to stability and development in the Greater East African Region.