Spring / Summer 2013 Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSCHS News Spring/Summer 2015

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / summer 2015 Righting a WRong After 125 Years, Hong Yen Chang Becomes a California Lawyer Righting a Historic Wrong The Posthumous Admission of Hong Yen Chang to the California Bar By Jeffrey L. Bleich, Benjamin J. Horwich and Joshua S. Meltzer* n March 16, 2015, the 2–1 decision, the New York Supreme California Supreme Court Court rejected his application on Ounanimously granted Hong the ground that he was not a citi- Yen Chang posthumous admission to zen. Undeterred, Chang continued the State Bar of California. In its rul- to pursue admission to the bar. In ing, the court repudiated its 125-year- 1887, a New York judge issued him old decision denying Chang admission a naturalization certificate, and the based on a combination of state and state legislature enacted a law per- federal laws that made people of Chi- mitting him to reapply to the bar. The nese ancestry ineligible for admission New York Times reported that when to the bar. Chang’s story is a reminder Chang and a successful African- of the discrimination people of Chi- American applicant “were called to nese descent faced throughout much sign for their parchments, the other of this state’s history, and the Supreme students applauded each enthusiasti- Court’s powerful opinion explaining cally.” Chang became the only regu- why it granted Chang admission is Hong Yen Chang larly admitted Chinese lawyer in the an opportunity to reflect both on our United States. state and country’s history of discrimination and on the Later Chang applied for admission to the Califor- progress that has been made. -

Becoming Chief Justice: the Nomination and Confirmation Of

Becoming Chief Justice: A Personal Memoir of the Confirmation and Transition Processes in the Nomination of Rose Elizabeth Bird BY ROBERT VANDERET n February 12, 1977, Governor Jerry Brown Santa Clara County Public Defender’s Office. It was an announced his intention to nominate Rose exciting opportunity: I would get to assist in the trials of OElizabeth Bird, his 40-year-old Agriculture & criminal defendants as a bar-certified law student work- Services Agency secretary, to be the next Chief Justice ing under the supervision of a public defender, write of California, replacing the retiring Donald Wright. The motions to suppress evidence and dismiss complaints, news did not come as a surprise to me. A few days earlier, and interview clients in jail. A few weeks after my job I had received a telephone call from Secretary Bird asking began, I was assigned to work exclusively with Deputy if I would consider taking a leave of absence from my posi- Public Defender Rose Bird, widely considered to be the tion as an associate at the Los Angeles law firm, O’Mel- most talented advocate in the office. She was a welcom- veny & Myers, to help manage her confirmation process. ing and supportive supervisor. That confirmation was far from a sure thing. Although Each morning that summer, we would meet at her it was anticipated that she would receive a positive vote house in Palo Alto and drive the short distance to the from Associate Justice Mathew Tobriner, who would San Jose Civic Center in Rose’s car, joined by my co-clerk chair the three-member for the summer, Dick Neuhoff. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2 UC Hastings College of the Law

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Hastings Law News UC Hastings Archives and History 11-1-1984 Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2 UC Hastings College of the Law Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/hln Recommended Citation UC Hastings College of the Law, "Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2" (1984). Hastings Law News. Book 132. http://repository.uchastings.edu/hln/132 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the UC Hastings Archives and History at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law News by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hastings College of the Law Nov. Dec. 1984 SUPREME COURT'S SEVEN DEADLY SINS "To construe and build the law - especially constitutional law - is 4. Inviting the tyranny of small decisions: When the Court looks at a prior decision to choose the kind of people we will be," Laurence H. Tribe told a and decides it is only going a little step further a!ld therefore doing no harm, it is look- ing at its feet to see how far it has gone. These small steps sometimes reduce people to standing-room-only audience at Hastings on October 18, 1984. Pro- things. fessor Tribe, Tyler Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard, gave 5. Ol'erlooking the constitutil'e dimension 0/ gOl'ernmental actions and what they the 1984 Mathew O. Tobriner Memorial Lecture on the topic of "The sa)' about lIS as a people and a nation: Constitutional decisions alter the scale of what Court as Calculator: the Budgeting of Rights." we constitute, and the Court should not ignore this element. -

IRA MARK ELLMAN Professor and Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar Sandra Day O'connor College of Law Arizona

IRA MARK ELLMAN Professor and Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law Arizona State University Tempe, Arizona 85287-7906 (480) 965-2125 http://www.law.asu.edu/HomePages/Ellman/ EDUCATION: J.D. Boalt Hall School of Law, University of California, Berkeley (June, 1973). Head Article Editor, California Law Review. Order of the Coif. M.A. Psychology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois (October, 1969). National Institute of Mental Health Fellowship. B.A. Psychology, Reed College, Portland, Oregon (May, 1967). Nominated, Woodrow Wilson Fellowship. JUDICIAL CLERKSHIPS: Associate Justice William O. Douglas United States Supreme Court, 1973-74. Associate Justice Mathew Tobriner, California Supreme Court, 1/31/72 through 6/5/72. PERMANENT AND VISITING AFFILIATIONS: 5/81 to Present: Professor of Law and (since 2001) Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar, Arizona State University. 9/2003 to Present Affiliate Faculty Member, Center for Child and Youth Policy, University of California at Berkeley. 9/2010 to 12/2010 Visiting Fellow Commoner, Trinity College, University of Cambridge 6/2007 to 12/2007 Visiting Scholar, Center for the Study of Law and Society, U.C. Berkeley 8/2006 to 12/2006 Visiting Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School 10/95 to 5/2001 Chief Reporter, American Law Institute, for Principles of the Law of Family Dissolution. Justice R. Ammi Cutter Reporter, from June, 1998. (Reporter, 10/92-10/95; Associate Reporter, 2/91 to 10/92). 8/2005 to 12/2005 Visiting Scholar, School of Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley 8/2004 to 12/2004 Visiting Scholar, Center for Law and Society, University of California, Berkeley 8/2003 to 12/2003 Visiting Scholar, Center for Law and Society, University of California, Berkeley 8/2000 to 5/2002 Visiting Professor, Hastings College of The Law, University of California. -

National Association of Women Judges Counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3

national association of women judges counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Poverty’s Impact on the Administration of Justice / 1 President’s Message / 2 Executive Director’s Message / 3 Cambridge 2012 Midyear Meeting and Leadership Conference / 6 MEET ME IN MIAMI: NAWJ 2012 Annual Conference / 8 District News / 10 Immigration Programs News / 20 Membership Moments / 20 Women in Prison Report / 21 Louisiana Women in Prison / 21 Maryland Women in Prison / 23 NAWJ District 14 Director Judge Diana Becton and Contra Costa County native Christopher Darden with local high school youth New York Women in Prison / 24 participants in their November, 2011 Color of Justice program. Read more on their program in District 14 News. Learn about Color of Justice in creator Judge Brenda Loftin’s account on page 33. Educating the Courts and Others About Sexual Violence in Unexpected Areas / 28 NAWJ Judicial Selection Committee Supports Gender Equity in Selection of Judges / 29 POVERTY’S IMPACT ON THE ADMINISTRATION Newark Conference Perspective / 30 OF JUSTICE 1 Ten Years of the Color of Justice / 33 By the Honorable Anna Blackburne-Rigsby and Ashley Thomas Jeffrey Groton Remembered / 34 “The opposite of poverty is justice.”2 These words have stayed with me since I first heard them Program Spotlight: MentorJet / 35 during journalist Bill Moyers’ interview with civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson. In observance News from the ABA: Addressing Language of the anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, they were discussing what Dr. Access / 38 King would think of the United States today in the fight against inequality and injustice. -

General Election November 6, 2018 Expanded Voter Information

General Election November 6, 2018 Expanded Voter Information Table of Contents: STATE GOVERNOR 1 LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR 3 SECRETARY OF STATE 4 CONTROLLER 5 TREASURER 6 ATTORNEY GENERAL 7 INSURANCE COMMISSIONER 8 MEMBER STATE BOARD OF EQUALIZATION 1st District 10 UNITED STATES SENATOR 10 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 29th District 13 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 30th District 13 STATE SENATOR 18th District 14 MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 45th District 15 MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 46th District 16 JUDICIAL 18 SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION 30 COUNTY ASSESSOR 32 COUNTY SHERIFF 33 STATE MEASURES 34 COUNTY MEASURES 45 CITY MEASURES 46 Prepared by Danica Bergagnini, Brandi McPherson, Kaitlin Vitek Formaker, Erin Huffer-Ethial, & Stephanie Del Barco. Political Action Network neither supports nor opposes political parties, ballot measures, or candidates for public office. This information was compiled via multiple internet sources such as media articles, candidate websites, candidate social media accounts, votersedge.org, and ballotpedia.org. Political Action Network politicalactionnetwork.org • [email protected] • fb & twitter @politicalactnet STATE GOVERNOR John H Cox Businessman/Taxpayer Advocate https://johncoxforgovernor.com/ Political Party: Republican A native of Chicago, Cox received his bachelor's from the University of Illinois at Chicago in accounting and political science. Cox's first involvement with politics was a 1976 run for a delegate position at the Democratic Convention. In 1980, Cox graduated from ITT/Chicago Kent College of Law and began working as an accountant. One year later, Cox founded a law firm and an accounting firm, followed by forays into investment advice, real estate, and venture capital. In 1991, Cox established a local branch of Rebuilding Together, a housing repair nonprofit. -

Judicial Rhetoric and Radical Politics: Sexuality, Race, and the Fourteenth Amendment

JUDICIAL RHETORIC AND RADICAL POLITICS: SEXUALITY, RACE, AND THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT BY PETER O. CAMPBELL DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Speech Communication with a minor in Gender and Women’s Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Associate Professor Cara A. Finnegan Associate Professor Pat Gill Associate Professor Thomas O’Gorman Associate Professor Siobhan B. Somerville ABSTRACT: “Judicial Rhetoric and Radical Politics: Sexuality, Race, and the Fourteenth Amendment” takes up U.S. judicial opinions as performances of sovereignty over the boundaries of legitimate subjectivity. The argumentative choices jurists make in producing judicial opinion delimit the grounds upon which persons and groups can claim existence as legal subjects in the United States. I combine doctrinal, rhetorical, and queer methods of legal analysis to examine how judicial arguments about due process and equal protection produce different possibilities for the articulation of queer of color identity in, through, and in response to judicial speech. The dissertation includes three case studies of opinions in state, federal and Supreme Court cases (including Lawrence v. Texas, Parents Involved in Community Schools vs. Seattle School District No. 1, & Perry v. Brown) that implicate U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy’s development and application of a particular form of Fourteenth Amendment rhetoric that I argue has liberatory potential from the perspective of radical (anti-establishmentarian and statist) queer politics. I read this queer potential in Kennedy’s substantive due process and equal protection arguments about gay and lesbian civil rights as a component part of his broader rhetorical constitution of a newly legitimated and politically regressive post-racial queer subject position within the U.S. -

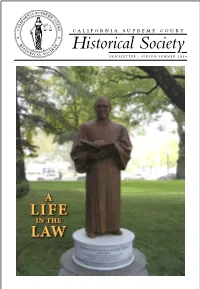

Highlights from a New Biography of Justice Stanley Mosk by Jacqueline R

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / summer 2014 A Life in The LAw The Longest-Serving Justice Highlights from a New Biography of Justice Stanley Mosk By Jacqueline R. Braitman and Gerald F. Uelmen* undreds of mourners came to Los Angeles’ future allies. With rare exceptions, Mosk maintained majestic Wilshire Boulevard Temple in June of cordial relations with political opponents throughout H2001. The massive, Byzantine-style structure his lengthy career. and its hundred-foot-wide dome tower over the bustling On one of his final days in office, Olson called Mosk mid-city corridor leading to the downtown hub of finan- into his office and told him to prepare commissions to cial and corporate skyscrapers. Built in 1929, the historic appoint Harold Jeffries, Harold Landreth, and Dwight synagogue symbolizes the burgeoning pre–Depression Stephenson to the Superior Court, and Eugene Fay and prominence and wealth of the region’s Mosk himself to the Municipal Court. Jewish Reform congregants, includ- Mosk thanked the governor profusely. ing Hollywood moguls and business The commissions were prepared and leaders. Filing into the rows of seats in the governor signed them, but by then the cavernous sanctuary were two gen- it was too late to file them. The secre- erations of movers and shakers of post- tary of state’s office was closed, so Mosk World War II California politics, who locked the commissions in his desk and helped to shape the course of history. went home, intending to file them early Sitting among less recognizable faces the next morning. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT DONALD E. DAWSON, No. 06-56454 Petitioner-Appellant, D.C. No. v. CV-04-00431-SGL JOHN MARSHALL, OPINION Respondent-Appellee. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California Stephen G. Larson, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted December 17, 2008—Pasadena, California Filed February 9, 2009 Before: Cynthia Holcomb Hall, Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain, and Richard A. Paez, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge O’Scannlain 1459 DAWSON v. MARSHALL 1461 COUNSEL Peter R. Afrasiabi, Turner Green LLP, Costa Mesa, Califor- nia, argued the cause for the appellant and filed the briefs. Heather M. Heckler, Deputy Attorney General for the State of California, Sacramento, California, argued the cause for the appellee and filed the brief. Edmund G. Brown, Jr., Attorney General of the State of California; Dane R. Gillette, Chief Assistant Attorney General; Julie L. Garland, Senior Assistant Attorney General; and Jennifer A. Neill, Supervising Deputy Attorney General; were also on the brief. OPINION O’SCANNLAIN, Circuit Judge: May an Article III judge decide a habeas petition on which he had issued findings and recommendations in his prior capacity as a magistrate judge? I Donald Dawson is serving a term of 26 years to life for the first degree murder of his ex-wife in the mid-1980s. In July of 2001, Dawson sought parole from the California Board of 1462 DAWSON v. MARSHALL Paroles, which found him unsuitable. After unsuccessfully petitioning for a writ of habeas corpus in California state court to overturn the board’s denial, Dawson filed a habeas petition in the Central District of California pursuant to 28 U.S.C. -

Supreme Court of California Statement on Equality and Inclusion June 11, 2020

Supreme Court of California Statement on Equality and Inclusion June 11, 2020 The Supreme Court of the State of California "In view of recent events in our communities and through the nation, we are at an inflection point in our history. It is all too clear that the legacy of past injustices inflicted on African Americans persists powerfully and tragically to this day. Each of us has a duty to recognize there is much unfinished and essential work that must be done to make equality and inclusion an everyday reality for all. We must, as a society, honestly recognize our unacceptable failings and continue to build on our shared strengths. We must acknowledge that, in addition to overt bigotry, inattention and complacency have allowed tacit toleration of the intolerable. These are burdens particularly borne by African Americans as well as Indigenous Peoples singled out for disparate treatment in the United States Constitution when it was ratified. We have an opportunity, in this moment, to overcome division, accept responsibility for our troubled past, and forge a unified future for all who share devotion to this country and its ideals. We state clearly and without equivocation that we condemn racism in all its forms: conscious, unconscious, institutional, structural, historic, and continuing. We say this as persons who believe all members of humanity deserve equal respect and dignity; as citizens committed to building a more perfect Union; and as leaders of an institution whose fundamental mission is to ensure equal justice under the law for every single person. In our profession and in our daily lives, we must confront the injustices that have led millions to call for a justice system that works fairly for everyone. -

A Salute to the Women Justices of the California Supreme Court

Left to right: Associate Justice Carol A. Corrigan, Associate Justice Joyce L. Kennard, Associate Justice Kathryn M. Werdegar, Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye, Associate Justice Ming W. Chin, Associate Justice Marvin R. Baxter and Associate Justice Goodwin Liu. Courtesy of the Supreme Court of California / Photo by Wayne Woods A Salute to the Women Justices of the California Supreme Court By R ay McDevitt* & Maureen B. Dear** n 1969, the year your editor graduated from law appointed Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye. At the Ischool, he was fortunate enough to have had the presentation ceremony the Chief Justice, in accept- opportunity to serve as a law clerk for the late Justice ing the award, announced that she was “proud that Raymond L. Sullivan of the California Supreme Court. the California Supreme Court now has a majority of At that time all seven of the justices on the Court were women.” men. That had been the case for the preceding 120 years, At some point in the future, there will have been so as was evident to anyone walking down the main corri- many women justices, of so many differing personal dor of the Court, its walls lined with the photographs of characteristics and judicial philosophies, that an article the justices, all male, who had served on the Court. This discussing a state Supreme Court comprised of a major- state of affairs would continue for another seven years, ity of women would no longer be newsworthy. But at until the controversial appointment of Rose Bird as this particular moment it does seem appropriate to take Chief Justice in 1977.