A Walk Through the Mass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liturgy of the Eucharist

1 Our Lady of Perpetual Help (June 18th, 2018) Part II: Liturgy of the Eucharist and Concluding Rite Introduction: Below you will find a detailed explanation of Part II: Liturgy of the Eucharist and Concluding Rite of the Mass, to assist you in learning more about the Mass and the changes that have occurred with the implementation of the third edition of the Roman Missal since Advent of 2011. This explanation was written by Fr. Victor De Gagné, The Prayer Intentions concludes the Liturgy of the Word and the focus of the Mass now shifts to the Liturgy of the Eucharist. Liturgy of the Eucharist: -The Collection & the Offering of the Gifts The collection and the offering of the bread and wine have been present in Christian worship since the very beginning. The gifts of the community are presented to the priest for the needs of the Church and of the poor. Justin the Martyr describes this collection and offering of gifts in his letter dating from the 2nd century: “Then someone brings bread and wine to him who presides over the assembly. They who have the means, give freely what they wish; and what is collected is placed in reserve with the presider, who provides help to the orphans, widows, and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in need, and prisoners, and traveling strangers; in a word, he takes care of all who are in need.” By the collection, we exercise Christian charity; sharing our blessings with those who have nothing. -The Preparation of the Gifts Once the gifts of bread and wine have been carried to the altar, the priest offers a prayer of blessing to God for his generosity, for the produce of the earth and for human labour which have created the gifts to be used for the Eucharist. -

Stand Priest: in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy

1 Stand Form B SIGN OF THE CROSS Priest: Have mercy on us, O Lord. Priest: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and People: For we have sinned against you. ✠of the Holy Spirit. Priest: Show us, O Lord, your mercy. People: Amen. People: And grant us your salvation. GREETING Form C Priest: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the Priest: You were sent to heal the contrite of heart: love of God, and the communion of the Holy Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Spirit be with you all. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: And with your spirit. Priest: You came to call sinners: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Or: People: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Priest: Grace to you and peace from God our Father Priest: You are seated at the right hand of the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. to intercede for us: People: And with your spirit. Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Or: Priest: The Lord be with you. People: And with your spirit. All forms of the Penitential Act are concluded by the Priest: PENITENTIAL ACT May almighty God have mercy on us, forgive us our Priest: Brethren, let us acknowledge our sins, and so sins, and bring us to everlasting life. prepare ourselves to celebrate the sacred mys- People: Amen. teries. Form A The Kyrie eleison invocations follow, unless they have just occurred All pause for silent reflection then say: in a formula of the Penitential Act (Form C). -

SAINT BASIL the GREAT ALTAR SERVER MANUAL Prayers of An

SAINT BASIL THE GREAT ALTAR SERVER MANUAL Prayers of an Altar Server O God, You have graciously called me to serve You upon Your altar. Grant me the graces that I need to serve You faithfully and wholeheartedly. Grant too that while serving You, may I follow the example of St. Tarcisius, who died protecting the Eucharist, and walk the same path that led him to Heaven. St. Tarcisius, pray for me and for all servers. ALTAR SERVER'S PRAYER Loving Father, Creator of the universe, You call Your people to worship, to be with You and each other at Mass. Help me, for You have called me also. Keep me prayerful and alert. Help me to help others in prayer. Thank you for the trust You've placed in me. Keep me true to that trust. I make my prayer in Jesus' name, who is with us in the Holy Spirit. Amen. 1 PLEASE SIGN AND RETURN THIS TOP SHEET IMMEDIATELY To the Parent/ Guardian of ______________________________(server): Thank you for supporting your child in volunteering for this very important job as an Altar Server. Being an Altar Server is a great honor – and a responsibility. Servers are responsible for: a) knowing when they are scheduled to serve, and b) finding their own coverage if they cannot attend. (email can help) The schedule is emailed out, prior to when it begins. The schedule is available on the Church website, and published the week before in the Church Bulletin. We have attached the, “St. Basil Altar Server Manual.” After your child attends the two server training sessions, he/she will most likely still feel unsure about the job – that’s OK. -

Liturgical Vestments

Saint Mary Magdalen Parish 2005 Berryman Street Berkeley, California 94709 “Together we share our faith in Jesus Christ. We live the Gospel, and we care for others.” DAILY MASS SCHEDULE WELCOME TO OUR COMMUNITY. Monday - Saturday: 8:00 am Monday - Friday: 5:30 pm We are delighted to have all of you here, and we SUNDAY LITURGY hope you will find our Saturday: 5:30 pm Vigil Mass parish a place where Sunday: 8:00, 9:30 & 11:00 am you grow spiritually, LITURGY OF THE HOURS put faith into action, Monday - Friday: 7:30 am & 5:15 pm Saturday: 7:30 am and encounter Jesus Christ. RECONCILIATION Saturdays: 4:00 pm - 5:00 pm Website: www.marymagdalen.org and by appointment PARISH OFFICE HOURS & PHONE NUMBERS Monday-Friday Office Phone (510) 526-4811 9:00 am - 5:00 pm Office Fax (510) 525-3638 Closed for Lunch: 2005 Berryman Street Noon - 1:00 pm Berkeley, CA 94709 Please Pray for the Newest Members of our Church: Neophytes Confirmed at the Easter Vigil Mandi Billinge Heather Bartow Sarah Mills Marcell Vazquez-Chanlatte James Kliegel Grant Nakamura Rose Ellis Parish & School Staff Parish Calendar: April-May 15, 2018 Fr. Nicholas Glisson, Pastor (ext. 112) April 22 4th Sunday Dinner for the Poor [email protected] Sunday 12:00 (set up); 3:00 pm (dinner), Parish Hall Norah Hippolyte, Business Manager April 22 CONCERT: Music Sources Sunday 5:00 pm, Church. ‘Trio Ignacio’ [email protected] (ext. 111) April 24 RCIA/Mystagogy Andy Canepa, Music Director (ext. 122) Tuesdays at 7:00 pm, Norton Hall [email protected] April 25 SPRED [Special Religious Education] Wednesdays at 6:00 pm, Norton Hall Heather Skinner, Director of Religious Education April 26 Faith Studies: Oremus-Catholic Prayer (510) 526-4744 [email protected] Thursdays at 7:00 pm in Norton Hall Dc. -

Respect for the Eucharist a Family Prayer Night Publication | Familyprayernight.Org

The Real Presence Project Today’s Topic Respect For The Eucharist A Family Prayer Night Publication | FamilyPrayerNight.org The Eucharist Is Jesus Christ IN THIS EDITION by Stephen J. Marino, Feast of Corpus Christi, 2018 Communitas Dei Patris The Eucharist Is Jesus Christ Do you love the Eucharist? I certainly do! But it wasn’t always that way for Lord The Basics Expanded And me because when I was a boy, and even in the Explained afterward for a time, I just took the Blessed Blessed Sacrament for granted. At times Ways To Reduce Abuses Of The Sacrament. I even questioned whether or not the Eucharist Certainly not by everyone, This is My Body little round host could really be Jesus. and I make no judgment as But, the nuns told me it was and so it Ways To End Abuses Once And to motives or intentions, but must have been true, right? I ended up For All objectively speaking there is leaving the Church and had no religious something seriously amiss in the Church convictions for 20 years. Thank God He Rights, Duties, Responsibilities today. Could it be a crisis of faith? didn’t give up on me. Like the prodigal son, it took a life-changing event for me I’ve seen consecrated hosts that to realize that the Eucharist did in fact have been thrown away, particles of Profanation: The act of mean everything to me…and I do mean consecrated bread (the Body of Christ) depriving something of everything. That was 33 years ago this left in unpurified Communion bowels, its sacred character; a month. -

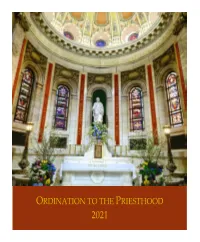

ORDINATION 2021.Pdf

WELCOME TO THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL Restrooms are located near the Chapel of Saint Joseph, and on the Lower Level, which is acces- sible via the stairs and elevator at either end of the Narthex. The Mother Church for the 800,000 Roman Catholics of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, the Cathedral of Saint Paul is an active parish family of nearly 1,000 households and was designated as a National Shrine in 2009. For more information about the Cathedral, visit the website at www.cathedralsaintpaul.org ARCHDIOCESE OF SAINT PAUL AND MINNEAPOLIS SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA Cover photo by Greg Povolny: Chapel of Saint Joseph, Cathedral of Saint Paul 2 Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis Ordination to the Priesthood of Our Lord Jesus Christ E Joseph Timothy Barron, PES James Andrew Bernard William Duane Duffert Brian Kenneth Fischer David Leo Hottinger, PES Michael Fredrik Reinhardt Josh Jacob Salonek S May 29, 2021 ten o’clock We invite your prayerful silence in preparation for Mass. ORGAN PRELUDE Dr. Christopher Ganza, organ Vêpres du commun des fêtes de la Sainte Vierge, op. 18 Marcel Dupré Ave Maris Stella I. Sumens illud Ave Gabrielis ore op. 18, No. 6 II. Monstra te esse matrem: sumat per te preces op. 18, No. 7 III. Vitam praesta puram, iter para tutum: op. 18, No. 8 IV. Amen op. 18, No. 9 3 HOLY MASS Most Rev. Bernard A. Hebda, Celebrant THE INTRODUCTORY RITES INTROITS Sung as needed ALL PLEASE STAND Priests of God, Bless the Lord Peter Latona Winner, Rite of Ordination Propers Composition Competition, sponsored by the Conference of Roman Catholic Cathedral Musicians (2016) ANTIPHON Cantor, then Assembly; thereafter, Assembly Verses Daniel 3:57-74, 87 1. -

Hereford Diocesan Newsletter August/September 2018 a Reminder

Hereford Diocesan Newsletter August/September 2018 A Reminder: Date of next Local Gathering in Hereford 22 September 2018 There will be a local diocesan gathering at Hereford on Saturday 22 September. Geraint Bowen, Artistic Director of this year’s festival, will talk about the Three Choirs Festival, and there will be tours of the Song School and the Cathedral gardens. We shall finish with tea and evensong. Please see the separate booking form for further details and do bring a friend – they might become members of FCM! Visit to the Vatican In the last newsletter we mentioned the honour that the cathedral choir had received in being the first Anglican cathedral choir to be invited to sing at the Papal Mass on the Feast of Sts Peter and Paul in St Peter’s Square, as well, as being invited to sing in a concert in the Sistine Chapel before the Pope and the ambassadors to the Holy See with the Sistine Chapel Choir. We are grateful to Ioan O’Reilly, one of the choristers, for writing his account of this momentous visit, which follows below. The service can be seen on YouTube, accessed via the Cathedral website. Rome Trip – 2018 This has been an amazing year for the choir; with performances attended by members of the Royal family and a home Three Choirs Festival! Yet by far the most exciting and exotic part of the year was the choir’s trip to Rome... The choir set out on its travels on Tuesday, 26th June, and in no time at all the fun of the trip had started when the organ scholar forgot his lunch (and upon realising that it was still in his fridge quickly sprinted off). -

Mass Coordinator Checklist for the Historic Church Before Mass • Arrive at Least 30 Minutes Prior to the Start of Mass

MC Checklist for the Historic Church October 2013 Mass Coordinator Checklist for the Historic Church Before Mass • Arrive at least 30 minutes prior to the start of Mass. • Take down the chain across the parking lot. • Unlock door of church. • Turn on interior lights and any appropriate exterior lights. • For a weekend Mass check the MC/Greeter/Usher notes (found on the Offertory table - cabinet behind pews on the left side of aisle) for any updates or changes for that Mass. • Turn the sound system on (located in the wooden cabinet in the Adoration Room). The button on the right of each box needs to be pushed in. You will know if they are both on if they turn green. Note that the button on the smaller device on top has to be pushed in for a few seconds before it turns green. • To check if they are both on properly see if the green light is on by the bottom of the microphone on the ambo. Lectionary • Turn on the fans if necessary. The switches for the fan are located in the same cabinet as the sound system. The switch to the left controls the speed of the fan. Fan Placard • Turn the altar and sanctuary lights on (switches are labeled inside the Adoration Room). • Turn the thermostat (by the sacristy door) up to 68 degrees. • For weekend Masses check the Presider’s Schedule to see who is celebrating (taped to the small refrigerator in the sacristy). If Fr. Frazier is not presiding or not has not yet arrived, get the appropriate vestments from the Parish Center and hang on the back of the door of Sacristy. -

Mass of Ordination to the Holy Priesthood June 27, 2020

Mass of Ordination To the Holy Priesthood June 27, 2020 Prayer for the Holy Father O God who in your providential design willed that your Church be built upon blessed Peter, whom you set over the other Apostles, look with favor, we pray, on Francis our Pope and grant that he, whom you have made Peter’s successor, may be for your people a visible source and foundation of unity in faith and of communion. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Excerpt from the English Translation of the Roman Missal ©2011, ICEL, All rights reserved. Most Reverend Michael R. Cote, D.D. Bishop of Norwich Prayer for the Bishop O God, eternal shepherd of the faithful, who tend your Church in countless ways and rule over her in love, grant, we pray, that Michael, your servant, whom you have set over your people, may preside in the place of Christ over the flock whose shepherd he is, and be faithful as a teacher of doctrine, a Priest of sacred worship and as one who serves them by governing. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Excerpt from the English translation of the Roman Missal ©2011, ICEL, All rights reserved 1 CELEBRATION OF THE ORDINATION TO THE PRIESTHOOD OF Reverend Michael Patrick Bovino for Service as Priest of the Diocese of Norwich Ritual Mass for the Conferral of Holy Orders Cathedral of Saint Patrick Norwich, Connecticut June 27, 2020 10:30 a.m. -

Epistles of St Paul

NOTES ON EPISTLES OF ST PAUL FROM UNPUBLISHED COMMENT ARIES. ~ • • • NOTES ON EPISTLES OF ST PAUL FROM UNPUBLISHED COMMENTARIES BY THE LATE J. B. LIGHTFOOT, D.D., D.C.L., LL.D., LORD BISHOP OF DURHAM. PUBLISHED BY THE TRUSTEES OF THE LIGHTFOOT FUND. lLonbon: MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK. 1895 [All Rights reserved.] i!tambribgc : PRINTED BY J. & C. F. CLAY, AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. INTRODUCTORY NOTE. HE present work represents the fulfilment of the under T taking announced in the preface to 'Biblical E~says' a year and a half ago. As that volume consisted of introduc tory essays upon New Testament subjects, so this comprises such of Dr Lightfoot's notes on the text as in the opinion of the Trustees of the Lightfoot Fund are sufficiently complete to justify publication. However, unlike 'Biblical Essays,' of which a considerable part had already been given to the world, this volume, as its title-page indicates, consists entirely of unpublished matter. It aims at reproducing, wherever possible, the courses of lectures delivered at Cambridge by Dr Lightfoot upon those Pauline Epistles which he did not live to edit in the form of complete commentaries. His method of trustiqg to his memory in framing sentences in the lecture room has been alluded to already in the preface to the previous volume. But here again the Editor's difficulty has been considerably lessened by the kindness of friends who were present at the lectures and have placed their note books at the disposal of the Trustees. As on the previous occasion, the thanks of the Trustees are especially due to W. -

= P^Fkqp=Mbqbo=^Ka=M^Ri=Loqelalu=`Ero`E

+ = = p^fkqp=mbqbo=^ka=m^ri=loqelalu=`ero`e NEWSLETTER February, 2012 Saints Peter and Paul Orthodox Church A Parish of the Orthodox Church in America Archpriest John Udics, Rector 305 Main Road, Herkimer, New York, 13350 Parish Web Page: www.cnyorthodoxchurch.org Saints Peter and Paul Orthodox Church Newsletter, February, 2012 This month’s Newsletter is in memory of Tillie Leve donated by Steve Leve. Parish Officer Contact Information Rector: Archpriest John Udics: (315) 866-3272 - [email protected] Committee President and Cemetery Director: John Ciko: (315) 866-5825 - [email protected] Committee Secretary: Subdeacon Demetrios Richards (315) 865-5382 – [email protected] Sisterhood President: Rebecca Hawranick: (315) 822-6517 – [email protected] Choir Director: Reader John Hawranick: (315) 822-6517 – [email protected] Birthdays in February – God Grant You Many Years! 8 – Audrey Gale 20 – Wayne Nuzum 10 – Larissa Lyszczarz 22 – Martha Mamrosch 11 – Eileen Brinck 27 – Marilyn Stevens 13 – Emilee Penree Memory Eternal. 1 Julia Hladysz (1981) 13 Helen Brown (1993) 1 Leonard Corman (1991) 14 Julia Bruska (2000) 1 Dorothy Quackenbusg (2005) 15 Owen Dulak 2 John Garbera (1988) 16 John Yaworski (1977) 2 Helen Woods (1998) 16 Anna Kuzenech (1996) 4 Andrew Keblish (1975) 17 Andrew Yaneshak (1984) 4 Paul Shust Jr (2008) 18 Michael Kuncik (1980) 5 Stephen Sleciak Sr (1972) 21 Peter Slenska (1986) 5 Efrosina Krenichyn (1977) 22 Julia Hudyncia (1983) 5 Olga Nichols (1994) 23 Mary Mezick )2000) 8 Antonina Steckler (2007) 24 John Hubiak 10 Harry Hardish (1975) 26 Helen Pelko (2005) 10 Helen Halkovitch (1989) 28 Andrew Homyk (1984) 10 Theodosia Jago (2007) 28 Cornelius Mamrosch (1995) 13 Natalie Raspey (1973) 28 Louis Brelinsky (2004 13 Andrew Bobak (1978) + Questions and Answers 75. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA the Missa Chrismatis: a Liturgical Theology a DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the S

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Missa Chrismatis: A Liturgical Theology A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Sacred Theology © Copyright All rights reserved By Seth Nater Arwo-Doqu Washington, DC 2013 The Missa Chrismatis: A Liturgical Theology Seth Nater Arwo-Doqu, S.T.D. Director: Kevin W. Irwin, S.T.D. The Missa Chrismatis (“Chrism Mass”), the annual ritual Mass that celebrates the blessing of the sacramental oils ordinarily held on Holy Thursday morning, was revised in accordance with the decrees of Vatican II and promulgated by the authority of Pope Paul VI and inserted in the newly promulgated Missale Romanum in 1970. Also revised, in tandem with the Missa Chrismatis, is the Ordo Benedicendi Oleum Catechumenorum et Infirmorum et Conficiendi Chrisma (Ordo), and promulgated editio typica on December 3, 1970. Based upon the scholarly consensus of liturgical theologians that liturgical events are acts of theology, this study seeks to delineate the liturgical theology of the Missa Chrismatis by applying the method of liturgical theology proposed by Kevin Irwin in Context and Text. A critical study of the prayers, both ancient and new, for the consecration of Chrism and the blessing of the oils of the sick and of catechumens reveals rich theological data. In general it can be said that the fundamental theological principle of the Missa Chrismatis is initiatory and consecratory. The study delves into the history of the chrismal liturgy from its earliest foundations as a Mass in the Gelasianum Vetus, including the chrismal consecration and blessing of the oils during the missa in cena domini, recorded in the Hadrianum, Ordines Romani, and Pontificales Romani of the Middle Ages, through the reforms of 1955-56, 1965 and, finally, 1970.