Systematics and Distribution Readings ➢ Texts: Copies on Reserve at Atherton Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russia's Ring of Fire

Russia’s Ring of Fire Kamchatka, the Commander & Kuril Islands 26th May to7th June 2021 (13 days) Zodiac cruise & Auklet flocks by N. Russ The Pacific Ring of Fire manifests itself in numerous places on the rim of the Pacific Ocean – but nowhere more dramatically than in Russia’s Far East. Along one of the world’s most active plate boundaries, the Pacific plate subducts under the Eurasian plate and the resulting volcanic and geothermal activity has built a unique and amazing landscape. Upwelling from the deep trenches formed by this action and currents around the many islands means there is an abundance of food for both birds and marine mammals, making the seas here amongst the richest in the world. The region’s human history is as interesting and as fascinating as the geological history and it is closely connected to the oceans that surround it. The earliest people to settle in the RBL Russia - Ring of Fire Itinerary 2 region, the Ainu, lived from the sea. Explorer Vitus Bering and, at the height of the Cold war, Russia’s formidable Pacific Fleet, were based in the region. The secrecy surrounding the fleet resulted in the region being ‘closed’ even to Russians, who had to obtain special permits to travel to and within the area. It is only now, two decades since Perestroika, that people can travel relatively freely here, although there is still very little in the way of infrastructure for visitors. This voyage takes us where very few people have been – or are able to go. The region falls into three quite distinct and unique geographical regions: the Kamchatka Peninsula, the Commander Islands (the western extremity of the Aleutian chain of islands) and the Kuril Islands. -

Field Guides Birding Tours Galapagos Iii 2012

Field Guides Tour Report GALAPAGOS III 2012 Aug 4, 2012 to Aug 14, 2012 George Armistead & Peter Freire The ubiquitous Blue-footed Booby is kind of the mascot of the Galapagos islands, enchanting visitors, be they bird watchers or not. In the islands, everybody loves boobies. (Photo by guide George Armistead) The Galapagos islands are a dream destination for every nature enthusiast, and we got to see first-hand why the enchanted isles are unique and so alluring, especially for birders. We arrived on Baltra and quickly made our way to the lovely Nemo II, and after settling in and meeting the friendly crew, we were off! Our first visit found us circling legendary Daphne Major, and we were extremely pleased to see a handful of Galapagos Martins working the top of the island for bugs. At North Seymour we were overrun with land iguanas, seeing about 20 of them, as we also side-stepped nesting frigatebirds and Blue-footed Boobies, and took note of our first Galapagos Doves. We sailed overnight for Floreana, where we had a nice hike amid the pirate caves, and tallied our only Medium Tree-Finches of the trip, before loading up and heading to the other side of the island. At Champion-by-Floreana we found a most confiding family of critically endangered Floreana Mockingbirds. That night we headed west for the Bolivar Channel, beginning the following day by walking the lava fields at Punta Moreno, tallying more great sightings of martins, enjoying lengthy studies of some very close flamingos and White-cheeked Pintails, and also noting all three types of cacti. -

The Forgotten Journey Huw Lewis-Jones Revisits a Pioneering, Ill-Fated Expedition to Map the Arctic

Vitus Bering, leader of the eighteenth-century Great Northern Expedition, died en route and was buried here, in the Commander Islands (pictured in 1980). POLAR EXPLORATION The forgotten journey Huw Lewis-Jones revisits a pioneering, ill-fated expedition to map the Arctic. he Great Northern Expedition was an Yet Bering’s brainchild books: Corey Ford’s Where the Sea Breaks Its immense eighteenth-century enter- was certainly one of Back (Little, Brown, 1966) and Steller’s Island prise that redrew the Arctic map. Led the largest, longest and (Mountaineers, 2006) by Dean Littlepage. Tby Danish captain Vitus Bering, it set out in most costly expedi- Bown’s synthesis of these “tragic and 1733 from St Petersburg, Russia. Over the tions mounted in the ghastly” final months is well written. He also next decade, a dwindling cavalcade crossed eighteenth century. goes to great lengths to detail the arduous thousands of miles of Siberian forest and Its budget, at around early phases, essentially an unending gauntlet swamp and then, in ships built by hand, 1.5 million roubles, of implausible logistics. Everything needed TARASEVICH/SPUTNIK/ALAMY V. struck out towards the unknown shores of was roughly one-sixth for the voyage — from shipbuilding gear North America. Sponsor Peter the Great of the annual income Island of the Blue and supplies to anchors, sails and cannon- had envisioned a grand campaign to elevate of the Russian state. As Foxes: Disaster balls — had to be hauled overland, by sledge, Russia’s standing in the world, with its scien- an example of commit- and Triumph horse and raft. -

89 Seabird 28 (2015)

Reviews REVIEWS Penguins: Their World, Their Ways By Tui articles are a master-class in the communi- De Roy, Mark Jones & Julie Cornthwaite. cation of scientific research to a much wider Christopher Helm, London. 2013. ISBN public than published papers would 978-1-4081-5212-6. Hundreds of colour normally reach. All the contributors are to be congratulated on the clarity and readability photographs, distribution maps. Hardback. of their accounts. I’m not going to pick out £35.00. any for particular comment, although it was I’ve long passed the age where I expect appropriate that it was given to Conrad much from birthday presents, but earlier this Glass (the ‘Rockhopper Copper’) to describe year I dropped a subtle hint to the wife well the unfortunate events of the 2011 MV in advance, and on the day was delighted to Oliva oil spill at Tristan da Cuhna. unwrap and flick through this book; reading it properly had to wait until the summer The final section (Species Natural History), field season ended! The format follows that compiled by Julie Cornthwaite, gives each of Albatross: Their World, Their Ways species a double-page spread summarising (reviewed in SEABIRD 22). First, the 18 facts and figures, and even these accounts species of penguin recognised here are average 8–9 colour photos. The only described in a series of essays covering the references in the book appear for each different taxonomic groups (e.g. Island species under Taxonomic source and Dandies: The Crested Penguins) in which Tui Conservation status, but these are not listed De Roy’s evocative text is almost lost among in full, although there is a short section on a multitude of stunning photographs, further reading and a very useful list of covering penguins in habitats ranging from websites where the reader can find out mangroves of the Galapagos, New Zealand’s much more information. -

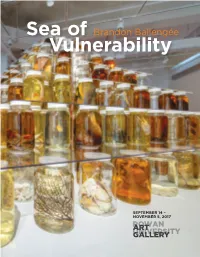

Brandon Ballengée Vulnerability

Sea of Brandon Ballengée Vulnerability SEPTEMBER 14 – NOVEMBER 5, 2017 ROWANART UNIVERSITYGALLERY ‘TRANSDISCIPLINARY’ IS HOW BEST TO DESCRIBE BRANDON BALLENGÉE’S PRACTICE. He is an artist, biologist and environmental educator who cre- ates artworks inspired from his ecological feldwork and lab- oratory research. His scientific research informs his artistic inquiry resulting in works that are balanced in its artistic and scientifc statements. In Sea of Vulnerability we presented a se- ries of his artworks in the form of installations, assemblages, and mixed media that ofer dramatic visual representations of species that are in decline, threatened, or already lost to extinc- tion. The results are beautifully composed artistic expressions that are also informative of some of our most pressing envi- ronmental issues. In his work Collapse for example we encounter a monumental pyramid of preserved aquatic specimens from the Gulf of Mexico meant to reference the fragile inter-relationship between gulf species and the food chain post the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the largest oil spill in human history. The narrative expressed in the work is dire, but visually the installation is a stun- ning example of formal visual aesthetics. The 455 jars (containing 370+ diferent species) are me- ticulously spaced into evenly measured rows punctuated by various shades of amber placed in purposeful sequences. The precision of the placement invites the viewer in where they encoun- ter the meaning in the work. As you follow the rows towards the top many of the glass jars are 1 Collapse: 2012, preserved specimens, glass and Carosafe preservative solutions, 9 x 12.8 x 12.8 feet, in scientifc collabora- tion with Todd Gardner, Jack Rudloe, Brian Schiering and Peter Warny courtesy of the artist and Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York. -

North American Animals Extinct in the Holocene

SNo Common Name\Scientific Name Extinction Date Range Mammals Prehistoric extinctions (beginning of the Holocene to 1500 AD) American Cheetahs 1 Miracinonyx trumani & Miracinonyx 11000 BC. Northern North America inexpectatus American Lion 2 11000 BC. USA, Canada and Mexico Panthera leo atrox American Mastodon 3 4080 BC. USA and Canada Mammut americanum American Mountain Deer 4 10000 BC. USA Odocoileus lucasi 5 Aztlanolagus agilis 10000 BC. Southeastern Arizona to Central America Beautiful Armadillo 6 8000 BC. USA to South America Dasypus bellus 7 Bison antiquus 10000 BC. USA and Canada 8 Bison occidentalis 5000 BC Alaska to Minnesota Blunt-toothed Giant Hutia 9 11000 BC. Northern Lesser Antilles Amblyrhiza inundata California Tapir 10 11000 BC. USA Tapirus californicus Camelops 11 8000 BC. USA and Mexico Camelops spp. Capromeryx 12 11000 BC. USA and Mexico Capromeryx minor 13 Caribbean Ground Sloths 5000 BC. Caribbean Islands Columbian Mammoth 14 5800 BC. USA and Mexico Mammuthus columbi Dire Wolf 15 8000 BC. North America Canis dirus Florida spectacled bear 16 8000 BC. USA Tremarctos floridanus Giant Beaver 17 Castoroides leiseyorum & Castoroides 11000 BC. Canada and USA ohioensis 18 Glyptodon 10000 BC. Central America Harlan's Muskox 19 9000 BC. North America Bootherium bombifrons Harrington's Mountain Goat 20 12000 BC. USA Oreamnos harringtoni 21 Holmesina septentrionalis 8000 BC. USA Jefferson's Ground Sloth 22 11000 BC. USA and Canada Megalonyx spp. Mexican Horse 23 11000 BC. USA and Mexico Equus conversidens 24 Mylohyus 9000 BC. North America Neochoerus spp. 25 11000 BC. Southeast USA to Panama Neochoerus aesopi & Neochoerus pinckneyi Osborn's Key Mouse 26 11000 BC. -

AMNH Digital Library

About 1.6 million people die of tuberculosis (TB) each year' mostly in developing nations lacking access to fast, accurate testing technology. TB is the current focus of the Foundation for Fino Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), established with ^" loundation ^ funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. for innovative new diagnostics FIND is dedicated to the advancement of diagnostic testing for infectious diseases in developing countries. For more information, visit www.finddiagnostics.org. Partnering against TB Twenty-two developing countries carry the burden culture from 42 days to as little as 10-14 days. In of 80 percent of the world's cases of TB, the addition, by identifying resistance to specific drugs, second-leading killer among infectious diseases the BD MGIT™ system provides fast and reliable and primary cause of death among people with information that can help physicians prescribe HIV/AIDS. The problem is compounded by TB's more effective treatments. All this can contribute resistance to drug treatment, limiting the options to the reduction in spread and mortality of TB, for over 450,000 patients annually. particularly in the HIV/AIDS population, where it is especially difficult to diagnose. BD is pleased to work with FIND to provide equipment, reagents, training and support to the Named one of America's Most Admired public health sector in high-burdened countries Companies' as well as one of the World's IVIost on terms that will enable them to purchase and Ethical Companies/ BD provides advanced medical implement these on a sustainable basis. technology to serve the global community's greatest needs. -

Arctic Biodiversity Assessment

142 Arctic Biodiversity Assessment Incubating red knot Calidris canutus after a snowfall at Cape Sterlegova, Taimyr, Siberia, 27 June 1991. This shorebird represents the most numerically dominating and species rich group of birds on the tundra and the harsh conditions that these hardy birds experience in the high Arctic. Photo: Jan van de Kam. 143 Chapter 4 Birds Lead Authors Barbara Ganter and Anthony J. Gaston Contributing Authors Tycho Anker-Nilssen, Peter Blancher, David Boertmann, Brian Collins, Violet Ford, Arnþór Garðasson, Gilles Gauthier, Maria V. Gavrilo, Grant Gilchrist, Robert E. Gill, David Irons, Elena G. Lappo, Mark Mallory, Flemming Merkel, Guy Morrison, Tero Mustonen, Aevar Petersen, Humphrey P. Sitters, Paul Smith, Hallvard Strøm, Evgeny E. Syroechkovskiy and Pavel S. Tomkovich Contents Summary ..............................................................144 4.5. Seabirds: loons, petrels, cormorants, jaegers/skuas, gulls, terns and auks .....................................................160 4.1. Introduction .......................................................144 4.5.1. Species richness and distribution ............................160 4.2. Status of knowledge ..............................................144 4.5.1.1. Status ...............................................160 4.2.1. Sources and regions .........................................144 4.5.1.2. Endemicity ..........................................161 4.2.2. Biogeography ..............................................147 4.5.1.3. Trends ..............................................161 -

The Causes of Avian Extinction and Rarity

The Causes of Avian Extinction and Rarity by Christopher James Lennard Town Cape of University Thesis submitted in the Faculty of Science (Department of Ornithology); University of Cape Town for the degree of Master of Science. June 1997 The University of Cape Town has been given the rllf'lt to reproduce this ~la In whole or In pil't. Copytlght is held by the autl>p'lr . ' The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Declaration: I I certify that this thesis results from my original investigation, except where acknowledged, and has not been submitted for a degree at any other university. Christopher J. Lennard Table of contents Page Table of contents ................................................................................................................ iii List oftigures ................................................................................................................... viii List of tables ....... :............................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgments ..................... , .................................... :.· ................................................. xii Abstract .............................................................................................................................. -

A Complete Guide to Arctic Wildlife, by Richard Sale

REVIEWS • 441 the men (and a few women) and machines behind the drift The introduction begins with an interesting discussion stations on either side of the geographic and ideological of alternative definitions of the Arctic based on (1) the divides in the Arctic. positions of the sun on the vernal and autumnal equinoxes I recommend the book, albeit with a few caveats. This and the summer and winter solstices, (2) the locations of is a popular history. Anyone looking for analysis and deep various polar water masses, (3) the extent of sea ice in the insight into superpower science in the Arctic will be North, (4) the approximate location of the timberline, i.e., disappointed; the book does not offer much detail about the northern limit of tree growth, (5) a measure of annual the many different scientific activities at drift stations, the incident solar energy per unit area, (6) the 10˚C (50˚F) scientific questions that were being addressed, the scien- summer isotherm, and (6) a modified version of the 10˚C tific and political rationale, the methods used and results summer isotherm that considers the mean temperature obtained, and the immediate and longer-term significance during the coldest winter month. The author adopts (p. 8) of the data. The book would have benefited from the the modified 10˚C summer isotherm definition as a “start- services of a good editor, as the prose is often turgid and ing point,” with exceptions made for some species and repetitive. Rather than letting the facts speak for them- circumstances described later in the book. -

The Evolution of Forelimb Morphology and Flight Mode in Extant Birds A

The Evolution of Forelimb Morphology and Flight Mode in Extant Birds A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Erin L. R. Simons August 2009 © 2009 Erin L. R. Simons. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled The Evolution of Forelimb Morphology and Flight Mode in Extant Birds by ERIN L. R. SIMONS has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick M. O'Connor Associate Professor of Anatomy Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT SIMONS, ERIN L. R., Ph.D., August 2009, Biological Sciences The Evolution of Forelimb Morphology and Flight Mode in Extant Birds (221 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Patrick M. O'Connor The research presented herein examines the morphology of the wing skeleton in the context of different flight behaviors in extant birds. Skeletal morphology was examined at several anatomical levels, including the whole bone, the cross-sectional geometry, and the microstructure. Ahistorical and historical analyses of whole bone morphology were conducted on densely-sampled pelecaniform and procellariiform birds. Results of these analyses indicated that the external morphology of the carpometacarpus, more than any other element, reflects differences in flight mode among pelecaniforms. In addition, elements of beam theory were used to estimate resistance to loading in the wing bones of fourteen species of pelecaniform. Patterns emerged that were clade-specific, as well as some characteristics that were flight mode specific. In all pelecaniforms examined, the carpometacarpus exhibited an elliptical shape optimized to resist bending loads in a dorsoventral direction. -

Arctic Seabirds: Diversity, Populations, Trends, and Causes

ARCTIC SEABIRDS: DIVERSITY, POPULATIONS, TRENDS, AND CAUSES ANTHONY J. GASTON Wildlife Research Division, Environment Canada, National Wildlife Research Centre, Ottawa K1A 0H3, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—Populations and trends of Arctic seabirds have been the subject of substantial research since the 1930s in Europe and Greenland and since the 1950s in North America. The marine waters of the Arctic support 44 species of seabirds comprising 20 genera. There are four endemic monotypic genera and an additional 25 species for which the bulk of the population is confined to Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. Most Arctic seabirds have large populations, with only two species comprising less than 100,000 individuals and many species numbering in the millions. Population trends for several widespread Arctic species have been negative in recent decades. Conversely, some sub-Arctic species are spreading northwards. Climate change with consequent changes in competition and predation, and intensifying development in the north, increasingly threaten Arctic seabirds. Changes in ice conditions are likely to have far-reaching and potentially irreversible results. Received 22 February 2011, accepted 26 May 2011. GASTON, A. J. 2011. Arctic seabirds: Diversity, populations, trends, and causes. Pages 147–160 in R. T. Watson, T. J. Cade, M. Fuller, G. Hunt, and E. Potapov (Eds.). Gyrfalcons and Ptarmigan in a Changing World, Volume I. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, Idaho, USA. http://dx.doi.org/10.4080/ gpcw.2011.0201 Key words: Seabirds, diversity, population size, population trends, Arctic. SEABIRDS HAVE PROVIDED A SOURCE OF FOOD for Census of Arctic seabird colonies began in the Arctic peoples throughout their history and 1930s in Greenland (Salomonsen 1950) and most major seabird colonies within the range Russia (Uspenski 1956), the 1950s in eastern of the post-Pleistocene Inuit expansion are Canadian Arctic (Tuck 1961), the 1960s in associated with archaeological sites that attest Spitzbergen (Norderhaug et al.