Historic Place Names of Peterborough And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victoria County Centennial History F 5498 ,V5 K5

Victoria County Centennial History F 5498 ,V5 K5 31o4 0464501 »» By WATSON KIRKCONNELL, M. A. PRICE $2.00 0U-G^5O/ Date Due SE Victoria County Centennial History i^'-'^r^.J^^, By WATSON KIRKCONNELL, M. A, WATCHMAN-WARDER PRESS LINDSAY, 1921 5 Copyrighted in Canada, 1921, By WATSON KIRKCONNELL. 0f mg brnttf^r Halter mtfa fell in artton in ttje Sattte nf Amiena Angnfit 3, ISiB, tlfia bnok ia aflfertinnatelg in^^iratei. AUTHOR'S PREFACE This history has been appearing serially through the Lindsaj "Watchman-Warder" for the past eleven months and is now issued in book form for the first time. The occasion for its preparation is, of course, the one hundredth anniversary of the opening up of Victoria county. Its chief purposes are four in number: — (1) to place on record the local details of pioneer life that are fast passing into oblivion; (2) to instruct the present generation of school-children in the ori- gins and development of the social system in which they live; (3) to show that the form which our county's development has taken has been largely determined by physiographical, racial, social, and economic forces; and (4) to demonstrate how we may, after a scien- tific study of these forces, plan for the evolution of a higher eco- nomic and social order. The difficulties of the work have been prodigious. A Victoria County Historical Society, formed twenty years ago for a similar purpose, found the field so sterile that it disbanded, leaving no re- cords behind. Under such circumstances, I have had to dig deep. -

A Reconnaissance Geophysical Survey of the Kawartha Lakes And

Document generated on 10/01/2021 4:57 p.m. Géographie physique et Quaternaire A Reconnaissance Geophysical Survey of the Kawartha Lakes and Lake Simcoe, Ontario Levé géophysique de reconnaissance des lacs Kawartha et du lac Simcoe, Ontario Eine geophysikalische Erkundung und Vermessung der Kawarthaseen und des Simcoesees, Ontario Brian J. Todd and C. F. Michael Lewis La néotectonique de la région des Grands Lacs Article abstract Neotectonics of the Great Lakes area A marine geophysical survey program has been conducted in lakes of southern Volume 47, Number 3, 1993 Ontario. The survey was designed to detect neotectonic features, if they exist, and to evaluate their geological importance. High-resolution single- and URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/032960ar multichannel seismic reflection profiling were used to delineate late- and DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/032960ar post-glacial sedimentary strata and structures, as well as the sediment/bedrock interface, in the Kawartha Lakes and Lake Simcoe. Results show that two seismostratigraphic sequences are common within the unconsolidated See table of contents overburden. The lower unit exhibits a parallel reflection configuration having strong reflection amplitudes, whereas the upper unit is acoustically transparent and overlies the lower unit conformably in some places and Publisher(s) unconformably in others. Both units vary in thickness within lakes and from lake to lake. Typical subbottom profiles of Precambrian rock surfaces are Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal rolling; those of Paleozoic rock surfaces are smooth. At one location in Lower Buckhorn Lake, tilted rock surfaces may be faulted but disturbance of ISSN overlying glacioge-nic sediments was not observed. -

Capsule Railway History of Peterborough County

23ae Peterborough County – A Capsule Railway History BACKGROUND Before the Railway Age, travel and the movement of goods in Upper Canada were primarily dependent on wa- terways, and primitive trails that passed for roads. Needless to say, both of these modes of transportation relied very much on the weather of the seasons. Agitation for a more efficient mode of transportation had started to build with the news of the new-fangled railroad, but the economic depression of 1837 and the years following were bad years for Upper Canada and for railway development, especially in view of the unsettled economic and political conditions in England, on whose financial houses the crucial investment in railway ventures de- pended. However, in 1849 the Province of Canada passed the Railway Guarantee Act which guaranteed the interest on loans for the construction of railways not less than 75 miles in length. It was this legislation that trig- gered Canada's railway building boom. While the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada (GTR), incorporated in 1852, busied itself with its trunk line along Lake Ontario, the waterfront towns were busy with their own railway ambitions. They saw themselves as gate- ways to the untapped resources of the "hinterland". Thus emerged a pattern of "development roads" from Whit- by, Port Hope, Cobourg, Trenton, Belleville, Napanee, Kingston, Brockville and Prescott. (Toronto had already led the way with its portage road to Collingwood, and later participated in additional development roads to Owen Sound and Coboconk.) North of Lake Ontario were rich natural resources and a rapidly expanding population as successive waves of immi- grants had to seek land further north from Lake Ontario. -

Committee of Adjustment

MUNICIPALITY OF TRENT LAKES COMMITTEE OF ADJUSTMENT May 2, 2017 Council Chambers, 4:30 PM Agenda Call to Order Page 1. Disclosure of Interest 2. Adoption of Minutes a) Meeting Held April 4, 2017 (3 - 7) Committee of Adjustment - Minutes - 04 Apr 2017 3. Minor Variance Applications a) A-17-09 (Paradise Vacation Properties) (8 - 16) Concession 11 Pt. Lot 4, 45R-14315 Part 1 (Harvey) Roll No. 1542-010-001-04711 35 Fire Route 36A Subject of Minor Variance: Garage A-17-09 Memo A-17-09 Site Plan A-17-09 Notice b) A-17-10 (French) (17 - 25) Concession 16, Pt. Lot 24, Plan 45R-2398, Part 2 (Harvey) Roll No. 1542-010-002-85601 39 Fire Route 111 Subject of Minor Variance: Garage A-17-10 Memo A-17-10 Site Plan A-17-10 Notice c) A-17-11 (Amerie/Hideaway Homes) (26 - 36) Concession 12, Pt. Lot 7 (Harvey) Roll No. 1542-010-001-17700 57 Fire Route 44 Subject of Minor Variance: Deck Expansion A-17-11 Memo A-17-11 Site Plan A-17-11 Notice d) A-17-12 (West/Boisvert) (37 - 50) All times provided on the agenda are approximate only and may be subject to change. Page 1 of 66 MUNICIPALITY OF TRENT LAKES COMMITTEE OF ADJUSTMENT TUESDAY, MAY 2, 2017 COUNCIL CHAMBERS, 4:30 P.M. AGENDA Concession 11, Lot 16, Plan 32, Lot 20 (Harvey) Roll No. 1542-010-002-36300 114 Peninsula Drive Subject of Minor Variance: Garage A-17-12 Memo A-17-12-Site Plan A-17-12 Notice e) A-17-13 (Blacklaw) (51 - 61) Concession 4, Pt. -

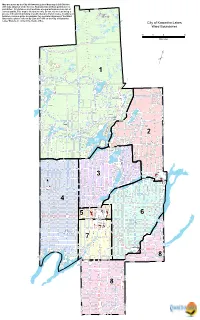

2018-Ward-Boundary-Map.Pdf

Map produced by the City of Kawartha Lakes Mapping & GIS Division with data obtained under license. Reproduction without permission is CON. 12 prohibited. All distances and locations are approximate and are not of Mi ria m D r Old Vic to ria R d Sickle Lake survey quality. This map is illustrative only. Do not rely on it as being a CON. 11 precise indicator of privately or publicity owned land, routes, locations or Crotchet Browns Andrews 0 Lake features, nor as a guide to navigate. For accurate reference of the Ward CON. 1 Lake Lake CON. 9 Boundaries please refer to By-Law 2017-053 on the City of Kawartha 6 4 2 Boot 12 10 8 16 14 22 20 Lake 26 24 32 30 28 Lakes Website or contact the Clerks office. 36 34 CON. 8 Murphy Lake North CON. 7 City of Kawartha Lakes Big Trout Longford Lake Lake Thrasher Lake CON. 6 Circlet Ward Boundaries Lake South Longford CON. 5 Lake Big Duck . 4 CON Lake 10 5 0 10 CON. 3 Logan Lake L o g a n L a ke CON. 2 Isl a n d A Kilometers Lo COeN. 1 ga n Lak R d d R CON. 13 e r i v R m a Victoria 13 e CON. h n ke s CON. 12 La i a L w e Hunters k L c Lake Bl a CON. 12 Bl a 11 c k Rd CON. R iv e r Jordans Lake CON. 11 ON. 10 l C i 2 a 6 4 r 2 10 8 T 14 1 18 16 24 22 20 m 26 l CON. -

Kawartha Lakes Agricultural Action Plan

Kawartha Lakes Agricultural Action Plan Growing success 1 Steering committee Matt Pecoskie – Chair, ADAB Rep Joe Hickson – VHFA Rep Judy Coward, OMAFRA Kelly Maloney – CKL Mark Torey – VHFA Rep Paul Reeds – ADAB Rep Phil Callaghan – ADAB Rep Additional volunteers BR+E interviewers Vince Germani – CKL Laurie Bell – CKL Lance Sherk – CKL Carolyn Puterbough - OMAFRA Supported by: 2 Prepared by: PlanScape Building community through planning 104 Kimberly Avenue Bracebridge, ON, P1L 1Y5 Telephone: 705-645-1556 Fax: 705-645-4500 Email: [email protected] PlanScape website 3 Contents Steering committee ............................................................................................................. 2 Additional volunteers ........................................................................................................... 2 Supported by: ...................................................................................................................... 2 Prepared by: ....................................................................................................................... 3 Contents .............................................................................................................................. 4 Importance of agriculture in the City of Kawartha Lakes ..................................................... 6 Consultation ........................................................................................................................ 6 Agricultural Action Plan ...................................................................................................... -

Rank of Pops

Table 1.3 Basic Pop Trends County by County Census 2001 - place names pop_1996 pop_2001 % diff rank order absolute 1996-01 Sorted by absolute pop growth on growth pop growth - Canada 28,846,761 30,007,094 1,160,333 4.0 - Ontario 10,753,573 11,410,046 656,473 6.1 - York Regional Municipality 1 592,445 729,254 136,809 23.1 - Peel Regional Municipality 2 852,526 988,948 136,422 16.0 - Toronto Division 3 2,385,421 2,481,494 96,073 4.0 - Ottawa Division 4 721,136 774,072 52,936 7.3 - Durham Regional Municipality 5 458,616 506,901 48,285 10.5 - Simcoe County 6 329,865 377,050 47,185 14.3 - Halton Regional Municipality 7 339,875 375,229 35,354 10.4 - Waterloo Regional Municipality 8 405,435 438,515 33,080 8.2 - Essex County 9 350,329 374,975 24,646 7.0 - Hamilton Division 10 467,799 490,268 22,469 4.8 - Wellington County 11 171,406 187,313 15,907 9.3 - Middlesex County 12 389,616 403,185 13,569 3.5 - Niagara Regional Municipality 13 403,504 410,574 7,070 1.8 - Dufferin County 14 45,657 51,013 5,356 11.7 - Brant County 15 114,564 118,485 3,921 3.4 - Northumberland County 16 74,437 77,497 3,060 4.1 - Lanark County 17 59,845 62,495 2,650 4.4 - Muskoka District Municipality 18 50,463 53,106 2,643 5.2 - Prescott and Russell United Counties 19 74,013 76,446 2,433 3.3 - Peterborough County 20 123,448 125,856 2,408 2.0 - Elgin County 21 79,159 81,553 2,394 3.0 - Frontenac County 22 136,365 138,606 2,241 1.6 - Oxford County 23 97,142 99,270 2,128 2.2 - Haldimand-Norfolk Regional Municipality 24 102,575 104,670 2,095 2.0 - Perth County 25 72,106 73,675 -

80 Acres 4,330 Feet of Shoreline

80 ACRES 4,330 FEET OF SHORELINE OFFICIAL PLAN DESIGNATED BOBCAYGEON, ON PIGEON LAKE SOLDEAST ST S RANCH RD STURGEON LAKE (LITTLE BOB CHANNEL) VIEW SOUTH EAST VIEW EAST Property is ideally located within the Please see Opportunity for City of Kawartha Document THE OFFERING prime waterfront Lakes and is in Centre for PIGEON LAKE development close proximity to further technical designated as local amenities CBRE Limited is pleased to offer for sale this property documents Urban Settlement and recreational located on Sturgeon Lake within walking distance previously Area in the activities in completed and to Downtown Bobcaygeon. Having previously Kawartha Lakes Bobcaygeon, provided for the been approved for 271 Singe Family lots, the Official Plan Fenelon Falls, expired Draft Plan property is within the Bobcaygeon Settlement Area, Lindsay and designated Residential, within the Bobcaygeon Peterborough Secondary Plan. The land is being offered on behalf of msi Spergel HIGHLIGHTS inc., solely in its capacity as court-appointed Receiver of Bobcaygeon Shores Developments Ltd. EAST ST S Offers will be reviewed upon receipt. SITE DETAILS DOWNTOWN BOBCAYGEON SIZE 82.3 acres 4,330 feet of shoreline 1,002 feet along East Street FRONTAGE South (Highway 36) 747 feet along Ranch Road KAWARTHA LAKES OFFICIAL PLAN Urban Settlement Areas Residential; Parks and Open BOBCAYGEON Space; Unevaluated Wetlands; SECONDARY PLAN ESI Floodplain Hazard Area STURGEON LAKE RANCH RD Residential Type One Special (LITTLE BOB CHANNEL) ZONING (R1-22/R1-23) (AS AMENDED) General Commercial (C1-2) & Community Facility (CF) There is currently no servicing to the Site. Municipal servicing has been identified, although SERVICING distribution and internal infrastructure will be required to be built at the developer’s expense. -

Otonabee - Peterborough Source Protection Area Other Drinking Water Systems

Otonabee - Peterborough Source Protection Area Other Drinking Water Systems Cardiff North Bay Paudash Georgian Bay CC O O U U N N T T Y Y OO F F Lake HALIBURTONHALIBURTON Huron Kingston Township of Highlands East Toronto Lake Ontario Minden Gooderham Ormsby Lake ErieCoe Hill Glen Alda Kinmount Apsley Catchacoma Township of Lake Anstruther Catchacoma LakeNorth Kawartha Mississauga Jack Lake CC O O U U N N T T Y Y OO F F Lake PETERBOROUGHPETERBOROUGH VU28 Township of Township of Galway-Cavendish and Harvey Havelock-Belmont-Methuen IslandsIslands inin thethe TrentTrent WatersWaters Burleigh Falls Buckhorn Lower Cordova Mines Bobcaygeon Buckhorn Stony Lake Lake Fenelon Falls IslandsIslands inin thethe Clear Lake TrentTrent WatersWaters Young's Point Blairton Upper C u r v e L a k e Township of Buckhorn C u r v e L a k e Douro-Dummer Lake FirstFirst NationNation Township of Havelock Smith-Ennismore-Lakefield Pigeon Lake Lakefield Warsaw Norwood CC I I T T Y Y OO F F Chemong Lake KAWARTHAKAWARTHA LAKESLAKES Bridgenorth Lindsay Township of 8 Asphodel-Norwood VU7 Campbellford Hastings VU7 CC I I T T Y Y OO F F PETERBOROUGHPETERBOROUGH Township of Municipality of Otonabee-South Monaghan Trent Hills Springville Keene Township of VU115 Cavan Monaghan Islands in the Islands in the Warkworth Janetville HH i i a a w w a a t t h h a a TrentTrent WatersWaters FirstFirst NationNation Roseneath VU7a Rice Lake Millbrook Harwood Bailieboro Gores Landing Castleton Pontypool Bewdley Centreton VU35 CC O O U U N N T T Y Y OO F F NORTHUMBERLANDNORTHUMBERLAND Garden Hill Brighton Elizabethville Camborne Kendal Baltimore Colborne THIS MAP has been prepared for the purpose of meeting the Legend provincial requirements under the Clean Water Act, 2006. -

BY E-MAIL November 2, 2017 the OEB Has Received Your June 29

Ontario Energy Commission de l’énergie Board de l’Ontario P.O. Box 2319 C.P. 2319 2300 Yonge Street 2300, rue Yonge 27th Floor 27e étage Toronto ON M4P 1E4 Toronto ON M4P 1E4 Telephone: 416-481-1967 Téléphone: 416-481-1967 Facsimile: 416-440-7656 Télécopieur: 416-440-7656 Toll free: 1-888-632-6273 Numéro sans frais: 1-888-632-6273 BY E-MAIL November 2, 2017 Joel Denomy Enbridge Gas Distribution Inc. Technical Advisor, Regulatory Applications 500 Consumers Road North York ON M2J 1P8 [email protected] Dear Mr. Denomy: Re: Enbridge Gas Distribution Inc. (Enbridge Gas) Bobcaygeon Pipeline Project (EB-2017-0260) and Scugog Island Pipeline Project (EB-2017-0261) The OEB has received your June 29, 2017 letter noting Enbridge Gas’ intention to file, by December 2017, applications for leave to construct natural gas pipelines to, and associated distribution system works in, the communities of Bobcaygeon, Ontario and Scugog Island, Ontario. Enbridge Gas also indicates that it will be seeking an order for a rate surcharge and a certificate of public convenience and necessity in relation to the project. Bobcaygeon is situated in the City of Kawartha Lakes. Enbridge Gas has a Municipal Franchise Agreement (MFA) with the City of Kawartha Lakes but will require a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity (Certificate) in order to construct natural gas works to and in Bobcaygeon. Scugog Island is situated in the Regional Municipality of Durham, in the Township of Scugog. Enbridge Gas has a MFA and Certificate for the Township of Scugog. The letter seeks the OEB’s guidance regarding any requirements for a competitive process that should be engaged prior to filing the applications. -

Annual Report 2009-10

Proudly Serving the Townships of Douro-Dummer Galway-Cavendish & Harvey North Kawartha Smith-Ennismore- Lakefield Annual 2010 2009 Report EAST KAWARTHA CHAMBE R. BUILDING BUSINESS . BUILDING COMMUNITY. Page 2 Dick Crawford, Crawford Building Consultants President’s Message Hello Chamber Members: Harassment policy. upgraded freight service, both of which will A year again has passed . With the Licence Bureau benefit the entire area. since our last Annual services now under Stay tuned. General Meeting and I am ServiceOntario, the nearing the end of my Chamber continues to . The Program and Events term as your President. upgrade the office with committee, through the Our Board and Chamber fresh paint and hot water able efforts of Chair staff have moved the improvements. Jenn Brown, her Chamber forward to committee, and provide new and better . The Public Policy Chair, Chamber staff, put on a programs and services for Esther Inglis, leads a great Gala last year. our members. Note the small but busy Special kudos to Mariann following: committee. They are Marlow for the golf tournament and Sally . The Chamber has working with the Federal Harding for the Wine & continued on the second Government to Food Pairing. The year of a three year strengthen the Chamber Committee is now marketing strategy. of Commerce voice on looking at recruiting Marketing Committee the upgrades to the members to plan more Chair, Jim Patterson, Trent Severn Waterway area-specific Chamber says we are on target. system and had an opportunity to provide activities. The Committee is pre-budget input at a . Our two-person focusing on providing recent Round Table Chamber office has done more marketing benefits event. -

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: an Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: An Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents Superior-Greenstone District School Board 2014 2 Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region Acknowledgements Superior-Greenstone District School Board David Tamblyn, Director of Education Nancy Petrick, Superintendent of Education Barb Willcocks, Aboriginal Education Student Success Lead The Native Education Advisory Committee Rachel A. Mishenene Consulting Curriculum Developer ~ Rachel Mishenene, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Edited by Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student and M.Ed. I would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their contribution in the development of this resource. Miigwetch. Dr. Cyndy Baskin, Ph.D. Heather Cameron, M.A. Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Martha Moon, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Brian Tucker and Cameron Burgess, The Métis Nation of Ontario Deb St. Amant, B.Ed., B.A. Photo Credits Ruthless Images © All photos (with the exception of two) were taken in the First Nations communities of the Superior-Greenstone region. Additional images that are referenced at the end of the book. © Copyright 2014 Superior-Greenstone District School Board All correspondence and inquiries should be directed to: Superior-Greenstone District School Board Office 12 Hemlo Drive, Postal Bag ‘A’, Marathon, ON P0T 2E0 Telephone: 807.229.0436 / Facsimile: 807.229.1471 / Webpage: www.sgdsb.on.ca Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region 3 Contents What’s Inside? Page Indian Power by Judy Wawia 6 About the Handbook 7