Dregs of Our Forgotten Ancestors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pottery Technology As a Revealer of Cultural And

Pottery technology as a revealer of cultural and symbolic shifts: Funerary and ritual practices in the Sion ‘Petit-Chasseur’ megalithic necropolis (3100–1600 BC, Western Switzerland) Eve Derenne, Vincent Ard, Marie Besse To cite this version: Eve Derenne, Vincent Ard, Marie Besse. Pottery technology as a revealer of cultural and symbolic shifts: Funerary and ritual practices in the Sion ‘Petit-Chasseur’ megalithic necropolis (3100–1600 BC, Western Switzerland). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, Elsevier, 2020, 58, pp.101170. 10.1016/j.jaa.2020.101170. hal-03051558 HAL Id: hal-03051558 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03051558 Submitted on 10 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 58 (2020) 101170 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Anthropological Archaeology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jaa Pottery technology as a revealer of cultural and symbolic shifts: Funerary and ritual practices in the Sion ‘Petit-Chasseur’ megalithic necropolis T (3100–1600 BC, -

272 Medals Were Awarded to 240 Breweries

Category 21: American-Belgo-Style Ale - 34 Entries Gold: Tank 7, Boulevard Brewing Co., Kansas City, MO Silver: Dear You, Ratio Beerworks, Denver, CO Bronze: Still Single, Light the Lamp Brewery, Grayslake, IL Category 22: American-Style Sour Ale - 36 Entries Gold: Vice Sans Fruit, Wild Barrel Brewing Co., San Marcos, CA Silver: Mirage, New Terrain Brewing Co., Golden, CO Bronze: Sour IPA, New Belgium Brewing Co., Fort Collins, CO Category 23: Fruited American-Style Sour Ale - 180 Entries Gold: Guava Dreams, Del Cielo Brewing Co., Martinez, CA Silver: Peach Afternoon, Port Brewing Co. / The Lost Abbey, San Marcos, CA 2020 WINNERS LIST Bronze: Summer Sun, Stereo Brewing Co., Placentia, CA Category 24: Brett Beer - 48 Entries Category 1: American-Style Wheat Beer - 59 Entries Gold: Bottle Conditioned Day Drinker, Lost Forty Brewing, Little Rock, AR Gold: Whoopty Whoop Wheat, Wild Ride Brewing, Redmond, OR Silver: Touch of Brett, Alesong Brewing & Blending, Eugene, OR Silver: Emmer, Lost Worlds Brewing, Cornelius, NC Bronze: Saison de Walt, Flix Brewhouse, Carmel, IN Bronze: 10 Barrel TWheat, 10 Barrel Brewing Co. - Bend Pub, Bend, OR Category 25: Mixed-Culture Brett Beer - 74 Entries Category 2: American-Style Fruit Beer - 125 Entries Gold: Wild James, Coldfire Brewing, Eugene, OR Gold: Strawberry Zwickelbier, Twin Sisters Brewing Co., Bellingham, WA Silver: Déluge, Sanitas Brewing Co., Boulder, CO Silver: Everything But The Seeds, 1623 Brewing Co., Eldersburg, MD Bronze: Gathering Red Currants & Peaches, Grimm Artisanal Ales, Brooklyn, -

Mother's North Grille Beer List

Mother's North Grille beer list ¶=Canned beer =Gluten Free ●=Low Cal (sad but true… items are limited & subject to change) ALL DAY Bucket specials ALL DAY pitcher specials 5 domestic bottled beers ($4 below)…………………………………$15.00 64oz Domestic Pitchers…............................................. $12.00 5 craft bottled beers of your choice, ($6 below)……………..$22.00 64oz Craft Beer Pitchers…........................................... $18.00 IPA Stouts & PORTERS Bell's Two Hearted • MI • 7% American IPA…………………………………….$7.00 Breckenridge Oatmeal Stout • CO • 4.95% …………………………….……$6.00 Dogfish 90 Minute IPA • DE • 9% American Double IPA……………………...………………..$8.00 Breckenridge Vanilla Porter • CO • 5.4% …………………………….……$6.00 ¶ Founders All Day IPA • MI • 4.7% American Session IPA……………………...………………..$6.00 DuClaw Sweet Baby Jesus • MD • 6.5% Porter..............................................................$7.00 Southern Tier IPA • NY • 7.3% American IPA………………………………………………..$6.00 Founders Breakfast Stout • MI • 8.3%……………………...………………..$7.00 ¶ Southern Tier Lake Shore Fog • NY • 6.5% NE IPA………………………………………………..$6.00 ¶ Union Snow Pants • MD • 8% English Oatmeal Stout………………………….$7.00 Lager ciders Abita Amber • LA • 4.5% Amber/Red Lager....................................................$5.50 ♥ Austin Eastciders Blood Orange • TX • 5%....................................$6.00 Brooklyn Lager • NY • 5.2% English Pale……………………………………………………….$6.00 ♥ Bold Rock Virginia Apple • VA • 4.7%……………………………………….$5.50 Corona Extra • Mexico • 4.6% Pale Lager…………………………..$5.00 ♥ -

817 CHRONOLOGY and BELL BEAKER COMMON WARE Martine

RADIOCARBON, Vol 51, Nr 2, 2009, p 817–830 © 2009 by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona CHRONOLOGY AND BELL BEAKER COMMON WARE Martine Piguet • Marie Besse Laboratory of Prehistoric Archaeology and Human Population History, Department of Anthropology and Ecology, University of Geneva, Switzerland. Email: [email protected] and [email protected]. ABSTRACT. The Bell Beaker is a culture of the Final Neolithic, which spread across Europe between 2900 and 1800 BC. Since its origin is still widely discussed, we have been focusing our analysis on the transition from the Final Neolithic pre-Bell Beaker to the Bell Beaker. We thus seek to evaluate the importance of Neolithic influence in the establishment of the Bell Bea- ker by studying the common ware pottery and its chronology. Among the 26 main types of common ware defined by Marie Besse (2003), we selected the most relevant ones in order to determine—on the basis of their absolute dating—their appear- ance either in the Bell Beaker period or in the pre-Bell Beaker groups. INTRODUCTION This study is part of a research project now ongoing for several years and directed by M Besse. Its objective is to better explain the Bell Beaker phenomenon. Two projects funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (FNS) made it possible to develop the study of the common ware pot- tery and its chronology (M Besse and M Piguet), territory analysis (M Besse and M Piguet), analysis of non-metric dental traits (J Desideri), and copper metallurgy (F Cattin). -

Beer and Malt Handbook: Beer Types (PDF)

1. BEER TYPES The world is full of different beers, divided into a vast array of different types. Many classifications and precise definitions of beers having been formulated over the years, ours are not the most rigid, since we seek simply to review some of the most important beer types. In addition, we present a few options for the malt used for each type-hints for brewers considering different choices of malt when planning a new beer. The following beer types are given a short introduction to our Viking Malt malts. TOP FERMENTED BEERS: • Ales • Stouts and Porters • Wheat beers BOTTOM FERMENTED BEERS: • Lager • Dark lager • Pilsner • Bocks • Märzen 4 BEER & MALT HANDBOOK. BACKGROUND Known as the ‘mother’ of all pale lagers, pilsner originated in Bohemia, in the city of Pilsen. Pilsner is said to have been the first golden, clear lager beer, and is well known for its very soft brewing water, which PILSNER contributes to its smooth taste. Nowadays, for example, over half of the beer drunk in Germany is pilsner. DESCRIPTION Pilsner was originally famous for its fine hop aroma and strong bitterness. Its golden color and moderate alcohol content, and its slightly lower final attenuation, give it a smooth malty taste. Nowadays, the range of pilsner beers has extended in such a way that the less hopped and lighter versions are now considered ordinary lagers. TYPICAL ANALYSIS OF PILSNER Original gravity 11-12 °Plato Alcohol content 4.5-5.2 % volume C olor6 -12 °EBC Bitterness 2 5-40 BU COMMON MALT BASIS Pale Pilsner Malt is used according to the required specifications. -

Haplogroup R1b (Y-DNA)

Eupedia Home > Genetics > Haplogroups (home) > Haplogroup R1b Haplogroup R1b (Y-DNA) Content 1. Geographic distribution Author: Maciamo. Original article posted on Eupedia. 2. Subclades Last update January 2014 (revised history, added lactase 3. Origins & History persistence, pigmentation and mtDNA correspondence) Paleolithic origins Neolithic cattle herders The Pontic-Caspian Steppe & the Indo-Europeans The Maykop culture, the R1b link to the steppe ? R1b migration map The Siberian & Central Asian branch The European & Middle Eastern branch The conquest of "Old Europe" The conquest of Western Europe IE invasion vs acculturation The Atlantic Celtic branch (L21) The Gascon-Iberian branch (DF27) The Italo-Celtic branch (S28/U152) The Germanic branch (S21/U106) How did R1b become dominant ? The Balkanic & Anatolian branch (L23) The upheavals ca 1200 BCE The Levantine & African branch (V88) Other migrations of R1b 4. Lactase persistence and R1b cattle pastoralists 5. R1 populations & light pigmentation 6. MtDNA correspondence 7. Famous R1b individuals Geographic distribution Distribution of haplogroup R1b in Europe 1/22 R1b is the most common haplogroup in Western Europe, reaching over 80% of the population in Ireland, the Scottish Highlands, western Wales, the Atlantic fringe of France, the Basque country and Catalonia. It is also common in Anatolia and around the Caucasus, in parts of Russia and in Central and South Asia. Besides the Atlantic and North Sea coast of Europe, hotspots include the Po valley in north-central Italy (over 70%), Armenia (35%), the Bashkirs of the Urals region of Russia (50%), Turkmenistan (over 35%), the Hazara people of Afghanistan (35%), the Uyghurs of North-West China (20%) and the Newars of Nepal (11%). -

July 2002 As Many of You Know, I Will Be Moving to Logan, PRESIDENT: Utah, at the End of This Month to Take a Teaching Royal Willard Position at Utah State University

This is the HOTV Brewsletter EDITOR'S NOTE VOLUME XXII, NUMBER 7 by Kendall Staggs July 2002 As many of you know, I will be moving to Logan, PRESIDENT: Utah, at the end of this month to take a teaching Royal Willard position at Utah State University. I'm excited about (541) 752-1314 the move, but wistful about leaving behind the VICE PRESIDENT: great folks of the Heart of the Valley Homebrew Scott Leonard Club. This will be my last brewsletter as editor, but (541) 752-0780 I hope to contribute some articles down the road. I NEWSLETTER EDITOR: also hope to visit Corvallis in the future, not only to Kendall Staggs see friends, but to find some good beer! Auf (541) 753-6538 Wiedersehen. CLUB TREASURER: Lee Smith In cerevisiae, fortis (In beer there is strength). (541) 926-2286 FESTIVAL DIRECTOR: PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL BEERFEST Joel Rea by Ron Hall (541) 758-1674 The Portland International Beerfest will be held THIS MONTH'S MEETING July 12-14, at a park near the Lloyd Center. You may want to get hotel rooms for the weekend or The Heart of the Valley Homebrew Club meets on coordinate drivers. The Lloyd Center is on the the third Wednesday of each month, alternating MAX line, so you can pretty much stay anywhere between Corvallis and Albany. Our next meeting downtown, as long as you are sober enough to find will be at 7:00 p.m. on July 17, at the home of Scott the train station afterward. I have a room at the and Karen Caul, 2930 NW Mulkey, Corvallis. -

Masonry QA Tap List 3:12

CRAFT BEER BEER CIDER DE RANKE/DUNHAM COMPLEXITÉ BELGIAN PALE 6 oz GREENWOOD SIDRA SIDRA .25L 6.5% a hoppy Belgian beer; zesty 8 6.9% an effervescent cider; sweet up front, tart on the back 8 FLENSBURGER PILS GERMAN PILSNER .5L WHITEWOOD KINGSTON BLACK, DABINETT, BROWNS .25L 4.8% sweet biscuity malt bill meets classic german noble hops 8 8.3% a bone dry cider of great complexity 8 GULDEN DRAAK SMOKE BELGIAN QUAD 6 oz 10.5% a rich, ruby hued Belgian beer; notes of sweet, smoked malt 8 HOLY MOUNTAIN BLACK BEER DARK ALE .5L 4.5% dry, roasty, & sessionable dark ale 7 WINE JESTER KING 2017 DAS WUNDERKIND SAISON 6oz BOTTLE POUR 4.5% a mixed culture, hoppy/funky farmhouse ale 6 BY THE GLASS OXBOW MONTAGE FRUITED FARMHOUSE ALE 6oz COUGAR CREST DEDICATION RED BLEND 6oz 6.5% sour & zesty ale blended w/ raspberries, oranges, & grapes 8 13.2% a rich, balanced blend of cab, merlot and syrah 14 OXBOW PLUM SYNTH FRUITED FARMHOUSE ALE 6oz PETRONI CORSE ROSÉ 6oz 7.5% a nicely tart, mixed fermentation beer with plums 10 12.5% vibrant w/ chalky minerality; strawberries & crushed flowers 12 SCRATCH BLACKBERRY CEDAR FARMHOUSE ALE 6oz PARDAS RUPESTRIS 6oz 5.5% notes of blackberries, juniper, and cedar bark 8 12% refreshing & bright, w/ lemony acidity & mineral finish 12 SCRATCH FILÉ FARMHOUSE FARMHOUSE ALE 6oz LESSE-FITCH CABERNET SAUVIGNON 6oz 4.5% a true Illinois beer, sweet sassafras and citrus notes 7 13.5% dark cherry & supple tannins profile w/ leathery nuance 13 SCRATCH MARIGOLD OAK LEAVES FARMHOUSE ALE 6oz MOOBUZZ PINOT NOIR 6oz 5% fresh, floral; like wild carnation and white oak leaves 8 13.8% red currant, dark cherry, rich mocha, w/ long, velvety finish 12 SKOOKUM TEMPLE RHYTHMS IPA .5L 6.7% juicy, hazy just the way you made me w/ a grapefruit bite 8 STILLWATER ON FLEEK IMPERIAL STOUT .25L 13% a big, rich dark beer with notes of chocolate and coffee 8 STILLWATER CELLAR DOOR SAISON 12oz NOT BOOZE 6.6% a spicy, earthy saison with white sage 8 FINCA COFFEE WAYFINDER CRUSHER DESTROYER SMOKED BOCK 16oz CAN cold brew 5 7.2% beech smoke, dried fruit, and oak. -

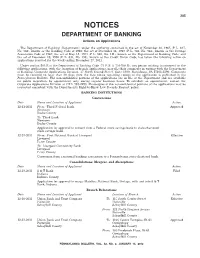

NOTICES DEPARTMENT of BANKING Actions on Applications

205 NOTICES DEPARTMENT OF BANKING Actions on Applications The Department of Banking (Department), under the authority contained in the act of November 30, 1965 (P. L. 847, No. 356), known as the Banking Code of 1965; the act of December 14, 1967 (P. L. 746, No. 345), known as the Savings Association Code of 1967; the act of May 15, 1933 (P. L. 565, No. 111), known as the Department of Banking Code; and the act of December 19, 1990 (P. L. 834, No. 198), known as the Credit Union Code, has taken the following action on applications received for the week ending December 27, 2011. Under section 503.E of the Department of Banking Code (71 P. S. § 733-503.E), any person wishing to comment on the following applications, with the exception of branch applications, may file their comments in writing with the Department of Banking, Corporate Applications Division, 17 North Second Street, Suite 1300, Harrisburg, PA 17101-2290. Comments must be received no later than 30 days from the date notice regarding receipt of the application is published in the Pennsylvania Bulletin. The nonconfidential portions of the applications are on file at the Department and are available for public inspection, by appointment only, during regular business hours. To schedule an appointment, contact the Corporate Applications Division at (717) 783-2253. Photocopies of the nonconfidential portions of the applications may be requested consistent with the Department’s Right-to-Know Law Records Request policy. BANKING INSTITUTIONS Conversions Date Name and Location of Applicant Action 12-21-2011 From: Third Federal Bank Approved Newtown Bucks County To: Third Bank Newtown Bucks County Application for approval to convert from a Federal stock savings bank to state-chartered stock savings bank. -

Iron Age Nomads of Southern Siberia in Craniofacial Perspective

ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 122(3), 137–148, 2014 Iron Age nomads of southern Siberia in craniofacial perspective Ryan W. SCHMIDT1,2*, Andrej A. EVTEEV3 1University of Montana, Department of Anthropology, Missoula, MT 59812, USA 2Kitasato University, School of Medicine, Department of Anatomy, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-0374, Japan 3Anuchin Research Institute and Museum of Anthropology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, 125009, Mokhovaya St., 11, Russia Received 9 April 2014; accepted 24 July 2014 Abstract This study quantifies the population history of Iron Age nomads of southern Siberia by ana- lyzing craniofacial diversity among contemporaneous Bronze and Iron Age (7th–2nd centuries BC) groups and compares them to a larger geographic sample of modern Siberian and Central Asian popula- tions. In our analyses, we focus on peoples of the Tagar and Pazyryk cultures, and Iron Age peoples of the Tuva region. Twentysix cranial landmarks of the vault and facial skeleton were analyzed on a total of 461 ancient and modern individuals using geometric morphometric techniques. Male and female cra- nia were separated to assess potential sexbiased migration patterns. We explore southern Siberian pop- ulation history by including Turkicspeaking peoples, a Xiongnu Iron Age sample from Mongolia, and a Bronze Age sample from Xinjiang. Results show that male Pazyryk cluster closer to Iron Age Tuvans, while Pazyryk females are more isolated. Conversely, Tagar males seem more isolated, while Tagar fe- males cluster amongst an Early Iron Age southern Siberian sample. When additional modern Siberian samples are included, Tagar and Pazyryk males cluster more closely with each other than females, sug- gesting possible sexbiased migration amongst different Siberian groups. -

Fuglesang Til Trykk.Indd

Ornament and Order Essays on Viking and Northern Medieval Art for Signe Horn Fuglesang Edited by Margrethe C. Stang and Kristin B. Aavitsland © Tapir Academic Press, Trondheim 2008 ISBN 978-82-519-2320-0 This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means; electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without permission. Layout: Tapir Academic Press Font: 10,5 pkt Adobe Garamond Pro Paper: 115 g Multiart Silk Printed and binded by 07-gruppen as This book has been published with founding from: Professor Lorentz Dietrichson og hustrus legat til fremme av kunsthistorisk forskning Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo Fritt Ord – The Freedom of Expression Foundation, Oslo Tapir Academic Press NO–7005 TRONDHEIM Tel.: + 47 73 59 32 10 Fax: + 47 73 59 84 94 E-mail: [email protected] www.tapir.no Table of Contents Preface . 7 Tabula Gratulatoria . 9 Erla Bergendahl Hohler Signe Horn Fuglesang – an Intellectual Portrait . 13 Eloquent Objects from the Early Middle Ages David M. Wilson Jellinge-style Sculpture in Northern England . 21 Anne Pedersen and Else Roesdahl A Ringerike-style Animal’s Head from Aggersborg, Denmark . 31 James Graham-Campbell An Eleventh-century Irish Drinking-horn Terminal . 39 Ornament and Interpretation Ulla Haastrup The Introduction of the Meander Ornament in Eleventh-century Danish Wall Paintings. Thoughts on the Symbolic Meaning of the Ornament and its Role in Promoting the Roman Church . 55 Kristin B. Aavitsland Ornament and Iconography. Visual Orders in the Golden Altar from Lisbjerg, Denmark . -

Mead Variants

Mead Variants (From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia) Tr6jniak - A Polish mead, made using two units of water for each unit of honey Acerglyn - A mead made with honey and maple syrup. Balche - A native Mexican version of mead. Black mead - A name sometimes given to the blend of honey and black currants. Bochet - A mead where the honey is caramelized or burned separately before adding the water. Yields toffee, chocolate, and marshmallow flavors. Braggot - Also called bracket or brackett. Originally brewed with honey and hops, later with honey and malt - with or without hops added. Welsh origin (bragawd). Capsicumel - A mead flavored with chili peppers. Chouchenn - A kind of mead made in Brittany. Cyser - A blend of honey and apple juice fermented together; see also cider. Czw5rniak (TSG) - A Polish mead, made using three units of water for each unit of honey Dandaghare - A mead from Nepal, combines honey with Himalayan herbs and spices. lt has been brewed since 1972 in the city of Pokhara. Dw6jniak(Tsc) - A Polish mead, made using equal amounts of water and honey Great mead - Any mead that is intended to be aged several years. The designation is meant to distinguish this type of mead from "short mead" (see below). Gverc or Medovina - Croatian mead prepared in Samobor and many other places. The word "gverc" or "gvirc' is from the German "Gewiirze" and refers to various spices added to mead. Hydromet - Literally "water-honey" in Greek. lt is also the French name for mead. (Compare with the Catalan hidromel, Galician aiguamel, Portuguese hidromel, ltalian idromele, and Spanish hidromiel and aguamiel).