A View from the Malaysian Parliament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELECTIONS ACT 1958 an Act Providing for Elections to the Dewan Rakyat and to the Legislative Assemblies of the States

ELECTIONS ACT 1958 An Act providing for elections to the Dewan Rakyat and to the Legislative Assemblies of the States. [Peninsular Malaysia, Federal Territory of Putrajaya - 28 August 1958;L.N.250/1958;. Sabah- Federal Territory of Labuan - l August 1965; P.U.176/1966. Sarawak-l November 1966, P.U.227/1967] PART 1PRELIMINARY Short title 1. This Act may be cited as the Elections Act 1958. Interpretation 2. In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires- "Adjudicating Officer" means the Adjudicating Officer appointed under section 8; "candidate" means a person who is nominated in accordance with any regulations made under this Act as a candidate for an election; "Chief Registrar ", "Deputy Chief Registrar", " Registrar", "Deputy Registrar " and "Assistant Registrar" mean respectively the Chief Registrar of Electors, Deputy Chief Registrar of Electors, Registrar of Electors, Deputy Registrar of Electors and Assistant Registrar of Electors appointed under section 8; "constituency" means a Parliamentary constituency or a State constituency, as the case may be; "Constitution" means the Federal Constitution; "election" means a Parliamentary election or a State election, as the case may be; "election officer" means an officer appointed under section 3 or 8 or any officer appointed for the purpose of conducting or assisting. in the conduct of any election, or registering or assisting in the registration of electors, underany regulations made under this Act; "elector" means a citizen who is entitled to vote in an election by virtue of Article -

Politik Dimalaysia Cidaip Banyak, Dan Disini Sangkat Empat Partai Politik

122 mUah Vol. 1, No.I Agustus 2001 POLITICO-ISLAMIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA IN 1999 By;Ibrahim Abu Bakar Abstrak Tulisan ini merupakan kajian singkat seJdtar isu politik Islam di Malaysia tahun 1999. Pada Nopember 1999, Malaysia menyelenggarakan pemilihan Federal dan Negara Bagian yang ke-10. Titik berat tulisan ini ada pada beberapa isupolitik Islamyang dipublikasikandi koran-koran Malaysia yang dilihat dari perspektifpartai-partaipolitik serta para pendukmgnya. Partai politik diMalaysia cidaip banyak, dan disini Sangkat empat partai politik yaitu: Organisasi Nasional Malaysia Bersatu (UMNO), Asosiasi Cina Ma laysia (MCA), Partai Islam Se-Malaysia (PMIP atau PAS) dan Partai Aksi Demokratis (DAP). UMNO dan MCA adalah partai yang berperan dalam Barisan Nasional (BA) atau FromNasional (NF). PASdan DAP adalah partai oposisipadaBarisanAltematif(BA) atau FromAltemattf(AF). PAS, UMNO, DAP dan MCA memilikipandangan tersendiri temang isu-isu politik Islam. Adanya isu-isu politik Islam itu pada dasamya tidak bisa dilepaskan dari latar belakang sosio-religius dan historis politik masyarakat Malaysia. ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^^ ^ <•'«oJla 1^*- 4 ^ AjtLtiLl jS"y Smi]?jJI 1.^1 j yLl J J ,5j^I 'jiil tJ Vjillli J 01^. -71 i- -L-Jl cyUiLLl ^ JS3 i^LwSr1/i VjJ V^j' 0' V oljjlj-l PoUtico-Islnndc Issues bi Malays bi 1999 123 A. Preface This paper is a short discussion on politico-Islamic issues in Malaysia in 1999. In November 1999 Malaysia held her tenth federal and state elections. The paper focuses on some of the politico-Islamic issues which were pub lished in the Malaysian newsp^>ers from the perspectives of the political parties and their leaders or supporters. -

New Politics in Malaysia I

Reproduced from Personalized Politics: The Malaysian State under Mahathir, by In-Won Hwang (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2003). This version was obtained electronically direct from the publisher on condition that copyright is not infringed. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior permission of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. Individual articles are available at < http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg > New Politics in Malaysia i © 2003 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies was established as an autonomous organization in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio- political, security and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are Regional Economic Studies (RES, including ASEAN and APEC), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is governed by a twenty-two-member Board of Trustees comprising nominees from the Singapore Government, the National University of Singapore, the various Chambers of Commerce, and professional and civic organizations. An Executive Committee oversees day-to-day operations; it is chaired by the Director, the Institute’s chief academic and administrative officer. © 2003 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore SILKWORM BOOKS, Thailand INSTITUTE OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES, Singapore © 2003 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore First published in Singapore in 2003 by Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Pasir Panjang Singapore 119614 E-mail: [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg First published in Thailand in 2003 by Silkworm Books 104/5 Chiang Mai-Hot Road, Suthep, Chiang Mai 50200 Ph. -

Johor No Longer an Umno Fortress, Says Chin Tong Malaysiakini.Com June 26, 2013 by Ram Anand

Johor no longer an Umno fortress, says Chin Tong MalaysiaKini.com June 26, 2013 By Ram Anand INTERVIEW The recent general election results in Johor proved that the southern state is no longer a fortress for Umno, said Kluang MP Liew Chin Tong, who is DAP's political strategist. In the 13th general election, Pakatan Rakyat focused heavily on making inroads in Johor, fielding prominent leaders, such as Liew himself along with Teo Nie Ching (now Kulai MP), and DAP supremo Lim Kit Siang (now Gelang Patah MP). NONEThey had only managed to obtain five out of the 26 parliamentary seats in the state, though it still represented a marked improvement from its sole parliament seat at the 2008 general election. "We were hoping to win between 10 to 15 parliamentary seats. But we always said that the minimum for us in Johor was going to be five seats. "We did win five, but PKR lost many seats with marginal differences - Pasir Gudang, Muar, Ledang, Segamat and Tebrau. DAP also lost Labis narrowly," he said during an interview with Malaysiakini last week. The majority for BN in these six seats was between 353 and 1,967 votes. dap kluang ceramah 200413 lim guan eng liew chin tong tan hong pin hu pang chaw suhaizan kaiat khairul faiziLiew, who is considered the brain behind DAP's southern campaign, said that nobody could be blamed for Pakatan's performance, and that on the whole, the lesson to be learnt from the Johor results was that the state is not a BN fortress. -

Pertanyaan Daripada Kawasan Tarikh So Alan

SOALAN NO.: 71 PERTANYAAN DEWAN RAKYAT PERTANYAAN LIS AN DARIPADA YB. TUAN GOBIND SINGH DEO KAWASAN PUC HONG TARIKH 20 MAC 2014, KHAMIS SO ALAN: YB. TUAN GOBIND SINGH DEO (PUCHONG} minta MENTERI KERJA RAY A menyatakan apakah langkah-langkah yang akan diambil oleh Kerajaan Pusat untuk memastikan dana yang dikeluarkan oleh Kerajaan untuk membaik pulih jalan-jalan Persekutuan dalam kawasan Parlimen Puchong diguna pakai dengan cepat dan efektif. 1 JAWAPAN: Tuan Yang Di-Pertua; Untuk makluman Ahli Yang Berhormat, berdasarkan semakan kementerian ini terdapat hanya satu Jalan Persekutuan sahaja yang diwartakan di dalam kawasan Parlimen Puchong iaitu Jalan Persekutuan FT 217 yang menghubungkan Sungai Besi ke Puchong sepanjang 4 km.. Kerja-kerja menyelenggara jalan tersebut dilaksanakan oleh syarikat konsesi yang dilantik iaitu Roadcare (M) Sdn. Bhd. di mana kerja-kerja penyenggaraan perlu mematuhi tempoh masa yang ditetapkan dalam perjanjian konsesi. Kerja-kerja penyenggaraan ini perlu disahkan oleh Jabatan Kerja Raya sebelum pembayaran dibuat kepada syarikat konsesi berkenaan. Manakala jalan-jalan utama di kawasan Parlimen Puchong terdiri daripada lebuhraya bertol, iaitu Lebuhraya Damansara - Puchong (LOP), Lebuhraya Shah Alam (KESAS) dan Lebuhraya Lembah Klang Selatan (SKVE) yang diselenggara masing-masing oleh syarikat konsesi lebuhraya berkenaan. Di samping itu untuk jalan-jalan negeri pula, peruntukan untuk menyelenggara adalah terletak di bawah Kerajaan Negeri Selangor menerusi geran peruntukan MARRIS dari Kerajaan Pusat. Sekian. Terima kasih . 2 NO. SO ALAN: 72 PEMBERITAHUAN PERTANYAAN BAGI JAWAB LISAN DEWAN RAKYAT PERTANYAAN JAWAB LISAN DARIPADA TUAN LIEW CHIN TONG [KLUANG] TARIKH 20 MAC 2014 RUJUKAN 6695 SO ALAN: Tuan Liew Chin Tong (Kiuang) minta MENTERI DALAM NEGERI menyatakan jumlah kes pemintasan e-mel, telekomunikasi dan pas dalam pecahan ahli politik, suspek jenayah dan orang awam oleh pihak kuasa di bawah peruntukan undang-undang pada tahun 1998 hingga 2014. -

Edisi 46 2.Cdr

DROWNING OR WAVING? CITIZENSHIP, MULTICULTURALISM AND ISLAM IN MALAYSIA Steven Drakeley Senior Lecturer, Asian and Islamic Studies University of Western Sydney Abstract This article examines some intriguing shifts in Islamic thinking on questions around citizenship and multiculturalism that have emerged in the Malaysian context in recent years. It does so in the light of the March 2008 election results and other recent political developments, notably the rise of Anwar Ibrahim’s PKR, and considers the implications for Malaysia. Of particular focus is the novel Islam Hadhari concept articulated by UMNO leader Prime Minister Badawi and the relatively doctrinaire Islamic state ideas of Islamist PAS. The article argues that these shifts in Islamic thinking are largely propelled by politics. Partly they are propelled by the logic, in a narrow political sense, imposed by the particular political circumstances that confront these Muslim-based political parties in Malaysia’s multi-ethnic, multi-religious setting. Partly the impetus is derived from growing general concerns in Malaysia that a new and more stable and enduring settlement of the issues associated with the country’s notorious horizontal divisions must be found if Malaysia is to avoid a disastrous plunge into communal conflict or tyranny. Keywords: citizenship, multiculturalism, Islam Hadhari, Bumiputera Steven Drakeley A. Introduction Citizenship, multiculturalism and Islam, and a broad range of associated issues interact in rather complex and unusual ways in Malaysia. Consequently, and because of its distinctive combination of social and political characteristics, Malaysia has consistently drawn considerable attention from political scientists, historians and sociologists. For the same reasons Malaysia is at the forefront of the current “global ijtihad” where many pressing contemporary problems confronting Muslim thinkers, policy makers and populations are being worked through. -

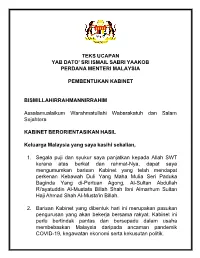

Teks-Ucapan-Pengumuman-Kabinet

TEKS UCAPAN YAB DATO’ SRI ISMAIL SABRI YAAKOB PERDANA MENTERI MALAYSIA PEMBENTUKAN KABINET BISMILLAHIRRAHMANNIRRAHIM Assalamualaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh dan Salam Sejahtera KABINET BERORIENTASIKAN HASIL Keluarga Malaysia yang saya kasihi sekalian, 1. Segala puji dan syukur saya panjatkan kepada Allah SWT kerana atas berkat dan rahmat-Nya, dapat saya mengumumkan barisan Kabinet yang telah mendapat perkenan Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Al-Sultan Abdullah Ri'ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah Ibni Almarhum Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Al-Musta'in Billah. 2. Barisan Kabinet yang dibentuk hari ini merupakan pasukan pengurusan yang akan bekerja bersama rakyat. Kabinet ini perlu bertindak pantas dan bersepadu dalam usaha membebaskan Malaysia daripada ancaman pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi serta kekusutan politik. 3. Umum mengetahui saya menerima kerajaan ini dalam keadaan seadanya. Justeru, pembentukan Kabinet ini merupakan satu formulasi semula berdasarkan situasi semasa, demi mengekalkan kestabilan dan meletakkan kepentingan serta keselamatan Keluarga Malaysia lebih daripada segala-galanya. 4. Saya akui bahawa kita sedang berada dalam keadaan yang getir akibat pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi dan diburukkan lagi dengan ketidakstabilan politik negara. 5. Berdasarkan ramalan Pertubuhan Kesihatan Sedunia (WHO), kita akan hidup bersama COVID-19 sebagai endemik, yang bersifat kekal dan menjadi sebahagian daripada kehidupan manusia. 6. Dunia mencatatkan kemunculan Variant of Concern (VOC) yang lebih agresif dan rekod di seluruh dunia menunjukkan mereka yang telah divaksinasi masih boleh dijangkiti COVID- 19. 7. Oleh itu, kerajaan akan memperkasa Agenda Nasional Malaysia Sihat (ANMS) dalam mendidik Keluarga Malaysia untuk hidup bersama virus ini. Kita perlu terus mengawal segala risiko COVID-19 dan mengamalkan norma baharu dalam kehidupan seharian. -

![Khamis, 10 Disember 2020 Mesyuarat Dimulakan Pada Pukul 10.00 Pagi DOA [Tuan Yang Di-Pertua Mempengerusikan Mesyuarat]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9684/khamis-10-disember-2020-mesyuarat-dimulakan-pada-pukul-10-00-pagi-doa-tuan-yang-di-pertua-mempengerusikan-mesyuarat-439684.webp)

Khamis, 10 Disember 2020 Mesyuarat Dimulakan Pada Pukul 10.00 Pagi DOA [Tuan Yang Di-Pertua Mempengerusikan Mesyuarat]

Naskhah belum disemak PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KEEMPAT BELAS PENGGAL KETIGA MESYUARAT KETIGA Bil. 51 Khamis 10 Disember 2020 K A N D U N G A N JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MENTERI BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Halaman 1) JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN LISAN BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Halaman 7) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DIBAWA KE DALAM MESYUARAT (Halaman 21) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Perbekalan 2021 Jawatankuasa:- Jadual:- Kepala B.45 (Halaman 23) Kepala B.46 (Halaman 52) Kepala B.47 (Halaman 101) USUL-USUL: Usul Anggaran Pembangunan 2021 Jawatankuasa:- Kepala P.45 (Halaman 23) Kepala P.46 (Halaman 52) Kepala P.47 (Halaman 101) Meminda Jadual Di Bawah P.M. 57(2) – Mengurangkan RM45 juta Daripada Peruntukan Kepala B.47 (Halaman 82) Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat (Halaman 83) Meminda Jadual Di Bawah P.M. 66(9) – Mengurangkan RM85,549,200 Daripada Peruntukan Kepala B.47 (Halaman 102) DR. 10.12.2020 1 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KEEMPAT BELAS PENGGAL KETIGA MESYUARAT KETIGA Khamis, 10 Disember 2020 Mesyuarat dimulakan pada pukul 10.00 pagi DOA [Tuan Yang di-Pertua mempengerusikan Mesyuarat] JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MENTERI BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN Tuan Karupaiya a/l Mutusami [Padang Serai]: Tuan Yang di-Pertua, saya minta dua minit, saya ada masalah di kawasan saya. Dua minit. Terima kasih Tuan Yang di-Pertua. Padang Serai ingin sampaikan masalah-masalah rakyat di kawasan, terutama sekali PKPD telah dilanjutkan di Taman Bayam, Taman Kangkung 1 dan 2, Taman Cekur Manis, Taman Sedeli Limau, Taman Bayam Indah, Taman Halia dan Taman Kubis di kawasan Paya Besar. Parlimen Padang Serai hingga 24 Disember 2020 iaitu selama empat minggu. -

Dewan Rakyat Parlimen Kedua Belas Penggal Kelima Mesyuarat Pertama

Naskhah belum disemak DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KEDUA BELAS PENGGAL KELIMA MESYUARAT PERTAMA Bil. 21 Rabu 18 April 2012 K A N D U N G A N RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DIBAWA KE DALAM MESYUARAT (Halaman 1) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Kanun Tatacara Jenayah (Pindaan)(No.2) 2012 (Halaman 2) Rang Undang-undang Keterangan (Pindaan)(No.2) 2012 (Halaman 12) Rang Undang-undang Laut Wilayah 2012 (Halaman 82) Rang Undang-undang Rukun Tetangga 2012 (Halaman 129) Rang Undang-undang Pasukan Sukarelawan Malaysia 2012 (Halaman 185) USUL-USUL: Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat (Halaman 1) Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat (Halaman 198) DR 18.4.2012 1 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT Rabu, 18 April 2012 Mesyuarat dimulakan pada pukul 10.00 pagi DOA [Timbalan Yang di-Pertua (Datuk Dr. Wan Junaidi bin Tuanku Jaafar) mempengerusikan Mesyuarat ] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DIBAWA KE DALAM MESYUARAT RANG UNDANG-UNDANG MESIN CETAK DAN PENERBITAN (PINDAAN) 2012 Bacaan Kali Yang Pertama Rang undang-undang bernama suatu akta untuk meminda Akta Mesin Cetak dan Penerbitan 1984; dibawa ke dalam Mesyuarat oleh Timbalan Menteri Dalam Negeri I [Datuk Wira Abu Seman bin Haji Yusop]; dibaca kali yang pertama; akan dibacakan kali yang kedua pada Mesyuarat kali ini. RANG UNDANG-UNDANG PROFESION UNDANG-UNDANG (PINDAAN) 2012 Bacaan Kali Yang Pertama Rang undang-undang bernama suatu akta untuk meminda Akta Profesion Undang- undang 1976; dibawa ke dalam Mesyuarat oleh Timbalan Menteri di Jabatan Perdana Menteri [Datuk Liew Vui Keong]: dibaca kali yang pertama; akan dibacakan kali yang kedua pada Mesyuarat kali ini. USUL WAKTU MESYUARAT DAN URUSAN DIBEBASKAN DARIPADA PERATURAN MESYUARAT 10.06 pg. -

WISMA REHDA Kelana Jaya, Petaling Jaya 31 January 2019

WISMA REHDA Kelana Jaya, Petaling Jaya 31 January 2019 Property Expo in Conjunction with Home Ownership Campaign (HOC) 2019 1 – 3 March 2019, Kuala Lumpur Convention Centre (KLCC) __________________________________________________________________________________________________________ As part of our ongoing support of efforts to encourage homeownership amongst the rakyat, t the Government’s Association (REHDA) Malaysia, in partnershiphe Real with Estatethe Ministry and Housingof Housing Developers’ and Local Government, will be organising a property expo at the Kuala Lumpur Convention Centre (KLCC) from 1 to 3 March 2019. The exposition is in conjunction with the Home Ownership Campaign (HOC) 2019 announced by the Minister of Finance Yang Berhormat Mr Lim Guan Eng during the tabling of Budget 2019 last November. The Association is synonymous with property exhibitions, having planned the highly successful Malaysia Property Expo (MAPEX) series for the past two decades. With HOC 2019, we aim to continue the spirit of MAPEX and cordially invite all developers, both REHDA members and non-members, to showcase their products under one roof in this nationwide affair. During the duration of the Campaign, which runs for six months between January and June 2019, Malaysian house-buyers will be exempted from stamp duties for residential units priced between RM300,000 and RM1 million while developers will be offering special discounts, thus making it the best time to look for and purchase the perfect home for you and your loved ones. For HOC 2019, we also call upon financial institutions to join us during the three- day event,“ as financing is an integral part of homeownership. We hope financial institutions will also play their part to offer attractive financing packages for purchasers to pick and choose the best option for them Chairman of the HOC Organising Committee. -

Malaysian Prime Minister Hosted by HSBC at Second Belt and Road Forum

News Release 30 April 2019 Malaysian Prime Minister hosted by HSBC at second Belt and Road Forum Peter Wong, Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive, the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, together with Stuart Milne, Chief Executive Officer, HSBC Malaysia, hosted a meeting for a Malaysian government delegation led by Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Prime Minister of Malaysia, with HSBC’s Chinese corporate clients. The meeting took place in Beijing on the sidelines of the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, in which Mr. Wong represented HSBC. Dr. Mahathir together with the Malaysian Ministers met with Mr. Wong and executives from approximately 20 Chinese companies to discuss opportunities in Malaysia in relation to the Belt and Road Initiative. Also present at the meeting were Saifuddin Abdullah, Minister of Foreign Affairs; Mohamed Azmin Ali, Minister of Economic Affairs; Darell Leiking, Minister of International Trade and Industry; Anthony Loke, Minister of Transport; Zuraida Kamaruddin, Minister of Housing and Local Government; Salahuddin Ayub, Minister of Agriculture and Agro- Based Industry; and Mukhriz Mahathir, Chief Minister of Kedah. Ends/more Media enquiries to: Marlene Kaur +603 2075 3351 [email protected] Joanne Wong +603 2075 6169 [email protected] About HSBC Malaysia HSBC's presence in Malaysia dates back to 1884 when the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited (a company under the HSBC Group) established its first office in the country, on the island of Penang, with permission to issue currency notes. HSBC Bank Malaysia Berhad was locally incorporated in 1984 and is a wholly-owned subsidiary of The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited. -

Mw Singapore

VOLUME 4, ISSUE 2 JUNE – DECEMBER 2018 MW SINGAPORE NEWSLETTER OF THE HIGH COMMISSION OF MALAYSIA IN SINGAPORE OFFICIAL VISIT OF PRIME MINISTER YAB TUN DR MAHATHIR MOHAMAD TO SINGAPORE SINGAPORE, NOV 12: YAB Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad undertook an official visit to Singapore, at the invitation of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Singapore, His Excellency Lee Hsien Loong from 12 to 13 November 2018, followed by YAB Prime Minister’s participation at the 33rd ASEAN Summit and Relat- ed Summits from 13 to 15 November 2018. The official visit was part of YAB Prime Minister’s high-level introductory visits to ASEAN countries after being sworn in as the 7th Prime Minister of Malaysia. YAB Tun Dr Mahathir was accompanied by his wife YABhg Tun Dr Siti Hasmah Mohd Ali; Foreign Minister YB Dato’ Saifuddin Abdullah; Minister of Economic Affairs YB Dato’ Seri Mohamed Azmin Ali and senior offi- cials from the Prime Minister’s Office as well as Wisma Putra. YAB Prime Minister’s official programme at the Istana include the Welcome Ceremony (inspection of the Guards of Honour), courtesy call on President Halimah Yacob, four-eyed meeting with Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong which was followed by a Delegation Meeting, Orchid-Naming ceremony i.e. an orchid was named Dendrobium Mahathir Siti Hasmah in honour of YAB Prime Minister and YABhg. Tun Dr Siti Hasmah Mohd Ali, of which the pro- grammes ended with an official lunch hosted by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and Mrs Lee. During his visit, YAB Prime Minister also met with the members of Malaysian diaspora in Singapore.