A Book of Imperfect Saints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

19 July 2020

CHURCH OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION AND ST. PAUL OF THE CROSS PRIMARY SCHOOL Sixteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time / A 19 July 2020 Catholic Parish of Dulwich Hill, Archdiocese of Sydney, Established in 1907 532 New Canterbury Road, Dulwich Hill NSW 2203 Ph: 9558 5308 Fax: 9558 4909 PO Box 149 Dulwich Hill NSW 2203 Ph: 9558-3257 Fax: 9559-3752 “The Spirit comes to help us in our weakness” Principal: Facebook: www.facebook.com/StPotC Website: dulwichhillparish.org.au Ms Frances Stewart Email: [email protected], or This sentence has often struck me as one that Paul wrote out of a deeply felt personal REC: Ms Jo-Anne Ross [email protected] experience. We look at St Paul’s life twenty centuries later and the impact he has had on the world and think of him as being extraordinarily successful. But did he consider Bishop Richard Umbers DD VG (Bishop in Residence) himself a success? Imagine him stepping off the boat at one of the great cities of the Fr. Andrew James (Parish Priest), (Deacon) Rev Louis Azzopardi ancient world - many thousands of people going about their daily life looking for success and happiness through their efforts and the blessing of the gods they worshipped. Preparation for First Reconciliation and Feast/Solemnity/Memorial/Saint Parish Office How would he start to speak of Christ who was crucified and rose from the dead? We Holy Communion of the Week Maria - Mondays know that he often experienced hostility and ridicule. In Ephesus his teachings provoked a (20 - 25 July 2020) Cecilia –Wed-Friday Now that restrictions on the number of people riot and in Athens they laughed at him when he spoke about the resurrection of the dead. -

Volume 4 Issue 4 September 2020 Many of You May Have Heard the About Renewing for Another Year

The Little Rose Newsletter The Voice of the Rose Ferron Foundation of Rhode Island Volume 4 Issue 4 September 2020 Many of you may have heard the about renewing for another year. For saying: “There’s a crack in everything, those of you who may have joined in that is how the light gets in.” This is a a month other than September, we line written by Leonard Cohen. will send out reminders via e-mail. Reflecting on this line, as one having a Membership not only supports our devotion to Little Rose, we begin to work but more importantly shows understand what Little Rose and the that there is still a strong devotion to year 2020 had in common. They both “Little Rose” and a need to keep her began in a healthy good way and then memory alive. both were shattered by a sickness that In whatever way our world has entered in. Sickness being the “crack” shifted through these challenging in both. times, we must, as Little Rose did in In our dealings with this change in imitation of, and in union with Jesus, our world, we have sadly decided to embrace what we have to suffer and cancel our fundraiser for this year. in this way God can and will channel We are thinking of different fundrais- the focus on another membership His light in order to fill all our broken ing avenues which we will share in the drive. If you joined as a yearly mem- places with His grace. future. For now we will try to keep ber last September, it is time to think We will persevere and overcome present difficulties. -

Profile of a Plant: the Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE By

Profile of a Plant: The Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE by Benjamin Jon Graham A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paolo Squatriti, Chair Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes Professor Richard P. Tucker Professor Raymond H. Van Dam © Benjamin J. Graham, 2014 Acknowledgements Planting an olive tree is an act of faith. A cultivator must patiently protect, water, and till the soil around the plant for fifteen years before it begins to bear fruit. Though this dissertation is not nearly as useful or palatable as the olive’s pressed fruits, its slow growth to completion resembles the tree in as much as it was the patient and diligent kindness of my friends, mentors, and family that enabled me to finish the project. Mercifully it took fewer than fifteen years. My deepest thanks go to Paolo Squatriti, who provoked and inspired me to write an unconventional dissertation. I am unable to articulate the ways he has influenced my scholarship, teaching, and life. Ray Van Dam’s clarity of thought helped to shape and rein in my run-away ideas. Diane Hughes unfailingly saw the big picture—how the story of the olive connected to different strands of history. These three people in particular made graduate school a humane and deeply edifying experience. Joining them for the dissertation defense was Richard Tucker, whose capacious understanding of the history of the environment improved this work immensely. In addition to these, I would like to thank David Akin, Hussein Fancy, Tom Green, Alison Cornish, Kathleen King, Lorna Alstetter, Diana Denney, Terre Fisher, Liz Kamali, Jon Farr, Yanay Israeli, and Noah Blan, all at the University of Michigan, for their benevolence. -

The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English

The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English A Revised Critical Edition Translated by Anna M. Silvas A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press Cover design by Jodi Hendrickson. Cover image: Wikipedia. The Latin text of the Regula Basilii is keyed from Basili Regula—A Rufino Latine Versa, ed. Klaus Zelzer, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, vol. 86 (Vienna: Hoelder-Pichler-Tempsky, 1986). Used by permission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Scripture has been translated by the author directly from Rufinus’s text. © 2013 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, micro- fiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Basil, Saint, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 329–379. The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English : a revised critical edition / Anna M. Silvas. pages cm “A Michael Glazier book.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8146-8212-8 — ISBN 978-0-8146-8237-1 (e-book) 1. Basil, Saint, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 329–379. Regula. 2. Orthodox Eastern monasticism and religious orders—Rules. I. Silvas, Anna, translator. II. Title. III. Title: Rule of Basil. -

August 1, 2021

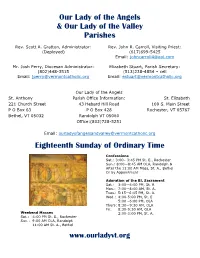

Our Lady of the Angels & Our Lady of the Valley Parishes Rev. Scott A. Gratton, Administrator: Rev. John R. Carroll, Visiting Priest: (Deployed) (617)699-5425 Email: [email protected] Mr. Josh Perry, Diocesan Administrator: Elizabeth Stuart, Parish Secretary: (802)448-3515 (513)238-4854 – cell Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Our Lady of the Angels St. Anthony Parish Office Information: St. Elizabeth 221 Church Street 43 Hebard Hill Road 169 S. Main Street P O Box 63 P O Box 428 Rochester, VT 05767 Bethel, VT 05032 Randolph VT 05060 Office:(802)728-5251 Email: [email protected] Eighteenth Sunday of Ordinary Time Confessions Sat.: 3:00– 3:45 PM St. E., Rochester Sun.: 8:00—8:45 AM OLA, Randolph & After the 11:00 AM Mass, St. A., Bethel Or by Appointment Adoration of the Bl. Sacrament Sat.: 3:00—4:00 PM, St. E. Mon.: 7:00—8:00 AM, St. A. Tues.: 5:15—6:15 PM, St. A. Wed.: 4:00-5:00 PM, St. E 5:00 –6:00 PM, OLA Thurs: 8:30—9:30 AM, OLA Fri: 8:30-9:30 AM, OLA Weekend Masses 2:00-3:00 PM, St. A. Sat.: 4:00 PM St. E., Rochester Sun.: 9:00 AM OLA, Randolph 11:00 AM St. A., Bethel www.ourladyvt.org 18th Sunday of Ordinary Time 1 August 2021 Remember your loved ones in the Holy Mass GARDENING ASSISTANCE NEEDED: – they will be forever grateful to you! CALLING ALL GARDENERS, or anyone that can help pull weeds, rake beds or otherwise be of help – on Saturday, July 31st – come and work THIS WEEKEND: at St. -

How Much Do You Know About Saint Brigid of Kildare? Read About Her in the Did You Know Article on Page 5, Which Will Help You Answer Some of the Questions Below

How much do you know about Saint Brigid of Kildare? Read about her in the Did You Know article on page 5, which will help you answer some of the questions below. Most importantly, she was a woman of great faith and loved the poor. Test your knowledge below and have fun. 1. Saint Brigid’s feast day is: 2. Which of these saints is not Check out page 6 a. January 29 a patron saint of Ireland and learn how b. February 1 a. St. Brendan St. Brigid played an important c. March 1 b. St. Brigid role in our c. St. Patrick d. August 8 #iamsaintbrigid e. October 20 d. St. Columba feature’s life! 3. What year was Saint Brigid born? 4. Saint Brigid is frequently a. 210 AD pictured with what animal: b. 451 AD a. Cow c. 485 AD b. Sheep d. 1076 AD c. Pig e. 1975 AD d. Chicken 5. Saint Brigid is the patron 6. True of False – The cross in our saint of all of these except: parish logo represents the a. Ireland woven cross Saint Brigid made b. Newborn babies out of reeds to help her explain Christianity to a c. Midwives dying pagan chieftan. d. Doctors e. Cattle 7. True or False – Saint Brigid’s 8. True or False – Saint Brigid 9. True or False – Saint Brigid father was happy she wanted was a disciple and was was born into slavery. to become a nun? baptized by Saint Patrick? 10. In Saint Brigid’s time beer was the daily drink of people because water was often polluted and beer was inexpensive. -

Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2012 The nbU ought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N. Boggs Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boggs, Richard N., "The nbouU ght Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature" (2012). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 21. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/21 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Mentor: Dr. Thomas Cook Reader: Dr. Gail Sinclair Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature By Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Project Approved: ________________________________________ Mentor ________________________________________ Reader ________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Dedicated to my wife Elizabeth for her love, her patience and her unceasing support. CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. Greek Pre-Chivalry 5 III. Roman Pre-Chivalry 11 IV. The Rise of Christian Chivalry 18 V. The Age of Chivalry 26 VI. -

&>Ff) Jottfck^ ^Di^Kcs<

fiEOHSTERED AS A NEWSPAPER. &>ff) jotTfCK^ ^di^KCs<. dltaf xoittiffi foiflj Spiritualism m <&xmt §ntaitt( THE SPIRITUALIST is regularly on Sale at the following places:—LONDON : xr, Ave Maria-lane, St. Paul’s Churchyard, E.C. PARIS: Kiosque 246, Boule- vard des Capucines, and 7, Rue de Lille. LEIPZIG: 2, Lindenstrasse. FLORENCE: Signor G. Parisi, Via della Maltonaia. ROME: Signor Bocca, Libraio, Via del Corso. NAPLES: British Reading Rooms, 267, Riviera di Chiaja, opposite the Villa Nazionale. LIEGE: 37, Rue Florimont. BUDA- PESTH : Josefstaadt Erzherzog, 23, Alexander Gasse. MELBOURNE : 96, Russell-street. SHANGHAI : Messrs. Kelly & Co. NEW YORK: Harvard Rooms, Forty-second-street & Sixth-avenue. BOSTON, U.S.: “Banner of Light” Office, 9, Montgomery-place. CHICAGO : “ Religio-Philosophical Journal” Office. MEMPHIS, U.S.: 7, Monroe-street. SAN FRANCISCO: 319, Kearney-street. PHILADELPHIA: 918, Spring Garden-street. WASHINGTON": No. xoio, Seventh-street. No. 316. (VOL. XIII.—No. 11.) LONDON: FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 1878. Published Weekly; Price Twopence. (Contents. BRITISH NATIONAL ASSOCIATION THE PSYCHOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OF SPIRITUALISTS, GREAT BRITAIN, Suggestions for the Future ... ...121 The Cure of Diseases near Sacred Tombs:—Extract 38, GREAT RUSSELL STREET, BLOOMSBURY W.O. 11, Chandos Street, Cavendish Square, London, W from a Letter Written by a Physician at Rome to his Entrance in Woburn Street. PRESIDENT—MR. SERJEANT COX. Sister, a Carmelite Nun, at Cavaillon, dated May 1, 1783—Extract from a Letter from an English Gentle- This Society was established in February. 1875, for the pro- man at Rome, dated June 11, 1783—Extract from a CALENDAR FOR SEPTEMBER. motion of psychological science in all its branches. -

Charlemagne Empire and Society

CHARLEMAGNE EMPIRE AND SOCIETY editedbyJoamta Story Manchester University Press Manchesterand New York disMhutcdexclusively in the USAby Polgrave Copyright ManchesterUniversity Press2005 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chaptersbelongs to their respectiveauthors, and no chapter may be reproducedwholly or in part without the expresspermission in writing of both author and publisher. Publishedby ManchesterUniversity Press Oxford Road,Manchester 8113 9\R. UK and Room 400,17S Fifth Avenue. New York NY 10010, USA www. m an chestcru niversi rvp ress.co. uk Distributedexclusively in the L)S.4 by Palgrave,175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010,USA Distributedexclusively in Canadaby UBC Press,University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, CanadaV6T 1Z? British Library Cataloguing"in-PublicationData A cataloguerecord for this book is available from the British Library Library of CongressCataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 7088 0 hardhuck EAN 978 0 7190 7088 4 ISBN 0 7190 7089 9 papaluck EAN 978 0 7190 7089 1 First published 2005 14 13 1211 100908070605 10987654321 Typeset in Dante with Trajan display by Koinonia, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Limited, Glasgow IN MEMORY OF DONALD A. BULLOUGH 1928-2002 AND TIMOTHY REUTER 1947-2002 13 CHARLEMAGNE'S COINAGE: IDEOLOGY AND ECONOMY SimonCoupland Introduction basis Was Charles the Great - Charlemagne - really great? On the of the numis- matic evidence, the answer is resoundingly positive. True, the transformation of the Frankish currency had already begun: the gold coinage of the Merovingian era had already been replaced by silver coins in Francia, and the pound had already been divided into 240 of these silver 'deniers' (denarii). -

Saint Alban and the Cult of Saints in Late Antique Britain

Saint Alban and the Cult of Saints in Late Antique Britain Michael Moises Garcia Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Institute for Medieval Studies August, 2010 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Michael Moises Garcia to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2010 The University of Leeds and Michael Moises Garcia iii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I must thank my amazing wife Kat, without whom I would not have been able to accomplish this work. I am also grateful to the rest of my family: my mother Peggy, and my sisters Jolie, Julie and Joelle. Their encouragement was invaluable. No less important was the support from my supervisors, Ian Wood, Richard Morris, and Mary Swan, as well as my advising tutor, Roger Martlew. They have demonstrated remarkable patience and provided assistance above and beyond the call of duty. Many of my colleagues at the University of Leeds provided generous aid throughout the past few years. Among them I must especially thcmk Thom Gobbitt, Lauren Moreau, Zsuzsanna Papp Reed, Alex Domingue, Meritxell Perez-Martinez, Erin Thomas Daily, Mark Tizzoni, and all denizens of the Le Patourel room, past and present. -

Spectral Clustering on Mercury Hollows: the Dominici Crater Case

Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017) 1329.pdf SPECTRAL CLUSTERING ON MERCURY HOLLOWS: THE DOMINICI CRATER CASE. A. Lucchetti1, M. Pajola2,3,1, G. Cremonese1, C. Carli4, G. A. Marzo5 and T. Roush3, 1INAF-Astronomical Observatory of Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, 35131 Padova, Italy ([email protected] ), 2Universities Space Research Association, NASA NPP Program (Supported by an appointment at NASA Ames Research Center: [email protected]), 3NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA; 4INAF-IAPS Roma, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali di Roma, Via del Fosso del Cavaliere, 00133 Rome, Italy; 5ENEA Centro Ricerche Casaccia, 00123 Rome, Italy. Introduction: The Mercury Dual Imaging System [8], i.e. incidence angle of 30°, emission angle of 0° (MDIS, [1]) onboard NASA MESSENGER (MErcury and phase angle of 30°. On the photometrically cor- Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and rected dataset we applied a statistical clustering over Ranging) spacecraft, provided the first global coverage the entire dataset based on a K-means partitioning al- of Mercury's surface with varying spatial resolution. gorithm [9]. It was developed and evaluated by [9-11] Early in the mission, high-resolution images showed and makes use of the Calinski and Harabasz criterion that specific areas exhibiting high reflectance and rela- [12] to find the intrinsically natural number of clusters, tive bluer in color were composed of shallow, irregular making the process unsupervised. A natural number of and rimless, flat-floored depressions with bright interi- ten clusters was identified within the crater and its ors and halos, often found on crater walls, rims, floors closest surroundings, see Fig.