The Challenge of Engaging Informal Security Actors in DFID's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bosire to (2012) the Bondo Secret Society: Female Circumcision and Th

Bosire, Obara Tom (2012) The Bondo secret society: female circumcision and the Sierra Leonean state. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3506/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] TITLE: THE BONDO SECRET SOCIETY: FEMALE CIRCUMCISION AND THE SIERRA LEONEAN STATE BY TOM OBARA BOSIRE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SCHOOL OF SOCIAL & POLITICAL SCIENCES COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW JANUARY, 2012 i Abstract This thesis explores the place of the Bondo secret society, whose precondition for membership is female genital cutting (FGC), in Sierra Leone’s post-war politics. The Bondo society is considered a repository of gendered knowledge that bestows members with significant forms of power in the local social context. Members, especially Bondo society leaders, are dedicated to the continued practice of FGC even amidst calls for its eradication. The Bondo is much sought after and overwhelmingly supported by the political elite due to the role it plays in ordering community life and its position as the depository of cultural repertoires (Swidler, 2001:24). -

Religion and Peacemaking in Sierra Leone

i RELIGION AND PEACEMAKING IN SIERRA LEONE Joseph Gaima Lukulay Moiba HCPS, Cand. Mag., PPU1&2, MA, Cand.Theol., PTE. Director of Studies: Prof. Bettina Schmidt, PhD, D.Phil. University of Wales: Trinity Saint David, Lampeter Second Supervisor: Dr Jenny Read-Heimerdinger, PhD, LicDD. University of Wales: Trinity Saint David, Lampeter STATEMENT: This research was undertaken under the auspices of the University of Wales: Trinity Saint David and was submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of PhD in the Faculty of Humanities and Performing Arts to the University of Wales: Trinity Saint David. SEPTEMBER 2016 ii Declaration This work has not previously been accepted as a whole or in part for any degree and has not been concurrently submitted for any degree. Signed: JGLMOIBAREV (Signed) (Candidate) Date: 8. 9. 2016 Statement 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnote giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed: JGLMOIBAREV (Signed) (Candidate) Date: 8. 9. 2016 Statement 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and abstract to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: JGLMOIBAREV (Signed) (Candidate) Date: 8. 9. 2016 iii Abstract: This thesis concerns religion as a peacemaking tool in Sierra Leone. The vast majority of people in Sierra Leone consider themselves to be Christians, Muslims and / or adherents of African Traditional Religion (ATR). -

THE REBEL WAR YEARS WERE CATALYTIC to DEVELOPMENT in the SOCIAL ADVANCEMENT of WOMEN in POST-WAR SIERRA LEONE” a Dissertation in Fulfilment for the Award Of

St. Clements University “THE REBEL WAR YEARS WERE CATALYTIC TO DEVELOPMENT IN THE SOCIAL ADVANCEMENT OF WOMEN IN POST-WAR SIERRA LEONE” A Dissertation In fulfilment For the Award of DDooccttoorr oo ff PPhhiilloossoopphhyy Submitted by: Christiana A.M. Thorpe B.A. Hons. Modern Languages Master of University Freetown – Sierra Leone May 2006 Dedication To the Dead: In Loving memory of My late Grandmother Christiana Bethia Moses My late Father – Joshua Boyzie Harold Thorpe My late Brother Julius Samuel Harold Thorpe, and My late aunty and godmother – Elizabeth Doherty. To the Living: My Mum: - Effumi Beatrice Thorpe. My Sisters: - Cashope, Onike and Omolora My Brothers: - Olushola, Prince and Bamidele My Best Friend and Guide: Samuel Maligi II 2 Acknowledgements I am grateful to so many people who have been helpful to me in accomplishing this ground breaking, innovative and what is for me a very fascinating study. I would like to acknowledge the moral support received from members of my household especially Margaret, Reginald, Durosimi, Yelie, Kadie and Papa. The entire membership and Institution of the Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) Sierra Leone Chapter has been a reservoir of information for this study. I thank Marilyn, Gloria and Samuel for their support with the Secretariat and research assistance. To the hundreds of interviewees for their timely responses, trust and confidence, I will ever remain grateful. To daddy for the endless hours of brainstorming sessions and his inspirational support. Finally I would like to convey my gratitude to Dr. Le Cornu for his painstaking supervision in making this study a reality. -

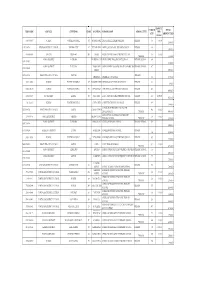

Emis Code Council Chiefdom Ward Location School Name

AMOUNT ENROLM TOTAL EMIS CODE COUNCIL CHIEFDOM WARD LOCATION SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL LEVEL PER ENT AMOUNT PAID CHILD 5103-2-09037 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 391 ROGBANGBA ABDUL JALIL ACADEMY PRIMARY PRIMARY 369 10,000 3,690,000 1291-2-00714 KENEMA DISTRICT COUNCIL KENEMA CITY 67 FULAWAHUN ABDUL JALIL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 380 3,800,000 4114-2-06856 BO CITY TIKONKO 289 SAMIE ABDUL TAWAB HAIKAL PRIMARY SCHOOL 610 10,000 PRIMARY 6,100,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO DOWN BALLOP ABDULAI IBN ABASS PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 694 1391-2-02007 6,940,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO TAMBA ABU ABDULAI IBNU MASSOUD ANSARUL ISLAMIC MISPRIMARY SCHOOL 407 1391-2-02009 STREET 4,070,000 5208-2-10866 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL WEST III PRIMARY ABERDEEN ABERDEEN MUNICIPAL 366 3,660,000 5103-2-09002 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 397 KOSSOH TOWN ABIDING GRACE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 62 620,000 5103-2-08963 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 373 BENGUEMA ABNAWEE ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOOL PRIMARY 405 4,050,000 4109-2-06695 BO DISTRICT KAKUA 303 KPETEMA ACEF / MOUNT HORED PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 411 10,000.00 4,110,000 Not found WARDC WATERLOO RURAL COLE TOWN ACHIEVERS PRIMARY TUTORAGE PRIMARY 388 3,880,000 ACTION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH 5205-2-09766 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL EAST III CALABA TOWN 460 10,000 DEVELOPMENT PRIMARY 4,600,000 ADA GORVIE MEMORIAL PREPARATORY 320401214 BONTHE DISTRICT IMPERRI MORIBA TOWN 320 10,000 PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 3,200,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO BONGALOW ADULLAM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 323 1391-2-01954 3,230,000 1109-2-00266 KAILAHUN DISTRICT LUAWA KAILAHUN ADULLAM PRIMARY -

Women and Post-Conflict Society in Sierra Leone Hazel M

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 12 | Issue 4 Article 9 Jul-2011 Women and Post-Conflict Society in Sierra Leone Hazel M. McFerson Recommended Citation McFerson, Hazel M. (2011). Women and Post-Conflict Society in Sierra Leone. Journal of International Women's Studies, 12(4), 127-147. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol12/iss4/9 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2011 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Women and Post-Conflict Society in Sierra Leone1 By Hazel M. McFerson2 Abstract Gender inequality in Sierra Leone, after colonialism among the worst in Sub-Saharan Africa, has been heightened further by the civil war of 1992-2002--which was related in part to the struggle for control of “blood diamonds” but also to long-standing social and regional disparities, and to collapse of formal institutions and widespread corruption. Sierra Leonean women are today among the most marginalized in the world, socially, economically and politically. However, there are differences among three groups: the better educated, comparatively richer “Krios” (descendants of the original freed slaves); relatively enlightened tribes; and the more traditional patriarchal tribes. The main route to improving the status of Sierra Leonean women is political empowerment. Some progress has been made since the civil war, post-conflict reconstruction programs and donor pressure are also opening up new opportunities for women progress, and there are hopes of significant electoral gains for women in the 2012 elections, inspired by the promising developments in neighboring post-conflict Liberia (which in 2005 elected Africa’s first female president). -

Post-War Regimes and State Reconstruction in Liberia and Sierra Leone

POST-WAR REGIMES AND STATE RECONSTRUCTION IN LIBERIA AND SIERRA LEONE Amadu Sesay Charles Ukeje Osman Gbla Olawale Ismail Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa prelim.pmd 1 20/07/2009, 20:25 © CODESRIA 2009 Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop, Angle Canal IV P.O. Box 3304 Dakar, 18524, Senegal Website: www.codesria.org ISBN: 978-2-86978-256-3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission from CODESRIA. Typesetting: Daouda Thiam Cover Design: Ibrahima Fofana Printing: Imprimerie Saint-Paul, Dakar, Senegal Distributed in Africa by CODESRIA Distributed elsewhere by African Books Collective, Oxford, UK. Website: www.africanbookscollective.com The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) is an independent organisation whose principal objectives are to facilitate research, promote research-based publishing and create multiple forums geared towards the exchange of views and information among African researchers. All these are aimed at reducing the fragmentation of research in the continent through the creation of thematic research networks that cut across linguistic and regional boundaries. CODESRIA publishes a quarterly journal, Africa Development, the longest standing Africa- based social science journal; Afrika Zamani, a journal of history; the African Sociological Review; the African Journal of International Affairs; Africa Review of Books and the Journal of Higher Education in Africa. The Council also co-publishes the Africa Media Review; Identity, Culture and Politics: An Afro-Asian Dialogue; The African Anthropologist and the Afro-Arab Selections for Social Sciences. -

Grassroots Perspectives of Peace Building in Sierra Leone 1991-2006

Coventry University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Grassroots perspectives of peace building in Sierra Leone 1991-2006 Cutter, Sue Award date: 2009 Awarding institution: Coventry University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of this thesis for personal non-commercial research or study • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission from the copyright holder(s) • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Grassroots Perspectives of Peace Building in Sierra Leone 1991-2006 Susan M. Cutter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2009 Coventry University ABSTRACT This study is about peace building in Sierra Leone, during and after the civil war (1991- 2002). The initial hypothesis was that the impact of externally driven peace building activities was reduced because of insufficient attention to local culture and priorities. This hypothesis was underpinned by a number of assumptions based on the author’s personal experience and the views of Sierra Leoneans met in the early post-war period. -

Explaining Women's Roles in the West African Tragic Triplet: Sierra Leone

Journal of Alternative Perspective s in the Social Sciences ( 2009 ) V ol 1, No 3, 808 -839 Explaining Women’s Roles in the West African Tragic Triplet: Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Cote d’Ivoire in Comparative Perspective Isiaka Alani Badmus , University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia Abstract: This paper is a critical examination of women’s roles in the West African civil conflicts of Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Cote d’Ivoire. Our epistemological point of departure is that women perform significant combat roles in war situations. Scholars/analysts have focused on women as solely victims of wars, but this study presents a framework that distances itself from this view and presents information on the wide variety of women’s involvement in conflicts. Thus, whilst the public life of politics that comprises war-making decision is being dictated by men, women are involved in many other roles in the field. Consequently, this study addresses the following research conundrums: What factors explain the increased ‘feminization of the militarization process’ associated with conflicts in West Africa? Are women voluntary partners in war or are they reluctant actors being manipulated by ruthless army officers/warlords? What are the implications of women’s active involvement in conflicts for the future development of women in these countries under focus, and society at large? What are the current and prospective roles of women in mediation and post-conflict peacebuilding? 1. Introduction: The Questions of Analysis This paper is a critical examination of women’s roles in the West African civil conflicts with emphasis on ‘the West African Tragic Triplet’—Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Cote d’Ivoire. -

Grassroots Perspectives of Peace Building in Sierra Leone 1991-2006 Cutter, S.M

Grassroots perspectives of peace building in Sierra Leone 1991-2006 Cutter, S.M. Submitted version deposited in CURVE April 2011 Original citation: Cutter, S.M. (2009) Grassroots perspectives of peace building in Sierra Leone 1991-2006. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Coventry: Coventry University. Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. A few images have been removed for copyright reasons. These include the images of 'conflict trees' from appendix D. The unabridged version of the thesis can be viewed at the Lanchester Library, Coventry University. CURVE is the Institutional Repository for Coventry University http://curve.coventry.ac.uk/open Grassroots Perspectives of Peace Building in Sierra Leone 1991-2006 Susan M. Cutter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2009 Coventry University ABSTRACT This study is about peace building in Sierra Leone, during and after the civil war (1991- 2002). The initial hypothesis was that the impact of externally driven peace building activities was reduced because of insufficient attention to local culture and priorities. This hypothesis was underpinned by a number of assumptions based on the author’s personal experience and the views of Sierra Leoneans met in the early post-war period. -

Université D'oran 2 Faculté Des Langues Étrangères THESE Pour L

Université d’Oran 2 Faculté des Langues étrangères THESE Pour l’obtention du diplôme de Doctorat en Sciences En Langue Anglaise A Nation’s Collapse: The Civil War Tactic and Impact Case Study: Sierra Leone (1991-2002) Présentée et soutenue publiquement par : Mme Maazouzi Karima Devant le jury composé de : BELMEKKI Belkacem Pr Université d’Oran 2 Président SAHEL Malika MCA E.N.S.B Alger Rapporteur BOUHADIBA Zoulikha Pr Université d’Oran 2 Examinateur MOULFI Leila Pr Université d’Oran 2 Examinateur DANI Fatiha MCA Université d’Oran 1 Examinateur HALLOUCHE Nadjouia MCA Université Sidi Belabbes Examinateur Année 2016-2017 Dedication I would like to dedicate this humble work to: My beloved parents, For whom I owe a special feeling of gratitude and wish a long happy life; My lovely brothers, Abdelhak and Amine, My sweet sisters, Soumia and Bahidja, For their sound advice, support and assistance; My dear husband, For his support and encouragement; My kind sisters in law, Nadia and Nour El Houda, My lovely niece and nephews: Aya, Wassim, and Anis, For whom I wish a successful future; My dear mother in law, My friends and All those who fight for peace. Acknowledgements First of all praise for the Almighty Allah for giving us insight, strength and the ability to accomplish this humble work. No words can express my heartfelt thanks to my supervisor Dr. Sahel Malika for her unwavering support, warm encouragement, prompt inspiration and sound advice. May God reward her for her meticulous scrutiny and patience. I’m so acknowledged in particular to Professor Borsali Fewzi for his overwhelming guidance, constant encouragement, suggestions and constructive criticism which contributed immensely in the evolution of my ideas during my research pursuit. -

14-2B2..- - Ll.{;- 3.0 2-

.sc~,- -O~-\4- ~\ (14-2b2..- - ll.{;- 3.0 2-) SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE In Trial Chamber I Before: Justice Pierre Boutet, Presiding Justice Bankole Thompson Justice Benjamin Mutanga Itoe Interim Registrar: Mr Lovemore Munlo Date: 5 December 2005 THE PROSECUTOR -against- SAMUEL HINGA NORMAN, MOININA FOFANA, and ALLIEU KONDEWA SCSL-2004-14-T FOFANA MATERIALS FILED PURSUANT TO THE CONSEQUENTIAL ORDER FOR COMPLIANCE WITH THE ORDER CONCERNING THE PREPARATION AND PRESENTATION OF THE DEFENCE CASE For the Office of the Prosecutor: For Moinina Fofana: Mr Luc Cote Mr Victor Koppe Mr James C. Johnson Mr Arrow Bockarie Ms Nina Jorgensen Mr Michiel Pestman Mr Mohammed Bangura Mr Andrew lanuzzi For Samuel Hinga Norman: Mr John Wesley Hall Dr Bu-Buakei Jabbi Ms Clare DaSilva Mr Kingsley Belle For Allieu Kondewa: Mr Charles Margai Mr Yada Williams Mr Ansu Lansana Ms Susan Wright Mr Martin Michael SCSL-2004-14-T SUBMISSIONS l. Considering the 'Consequential Order for Compliance with the Order Concerning the Preparation and Presentation of the Defence Case', filed by Trial Chamber I on 28 November 2005' (the "Consequential Order"), the Defence hereby submits the following materials in partial compliance thereof. 2. Noting that the Chamber has yet to deliver a decision on the 'Urgent Fofana Motion for Reconsideration ofthe 25 November 2005 Oral Ruling and the 28 November 2005 Consequential Order of Trial Chamber }'2 (the "Motion for Reconsideration"), the Defence respectfully submits that-for reasons now exhaustively canvassed compliance with paragraphs (a)(i) and (d) of the Consequential Order, at this point of the proceedings, would seriously compromise certain rights afforded to Mr Fofana. -

Payment of Tuition Fees to Primary Schools in Freetown City Council for Second Term 2019/2020 School Year

PAYMENT OF TUITION FEES TO PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL FOR SECOND TERM 2019/2020 SCHOOL YEAR Amount No. EMIS Name Of School District Chiefdom Address Headcount Total to School Per Child 1 Off Johnson Drive, 1 420806201 Aberdeen Municipal Primary School Infants Am FCC West III 306 10000 3,060,000 Aberdeen. Kallon Drive, 2 420806202 Aberdeen Municipal Primary School Juniors Pm FCC West III 366 10000 3,660,000 Aberdeen 2 Yonie Drive, 3 420502204 Action For Children And Youth Development Primary School FCC East III Off Gassama Street, 460 10000 4,600,000 Calaba Town. 4 423360765 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School FCC West II Dwarzark 364 10000 3,640,000 George Brook, 5 420703202 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School FCC West II 384 10000 3,840,000 Dwarzark 6 420401211 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School FCC East III Kissy Up-Hill 630 10000 6,300,000 Upper Beccle Street, 7 420507229 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School A.M FCC East III 710 10000 7,100,000 Kuntorlon, Wellington 8 420407208 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Am FCC East I Boyle Street 603 10000 6,030,000 Upper Maxwell Street, 9 420507229 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Am FCC East III 791 10000 7,910,000 Wellington. 10 420404201 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Pm FCC East I 15 Boyle Street 565 10000 5,650,000 11 420407208 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Pm FCC East I 15 Boyle Street 538 10000 5,380,000 Upper Maxwell Street, 12 420507230 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Pm FCC East III 690 10000 6,900,000 Wellington.